Gina Corcillo

advertisement

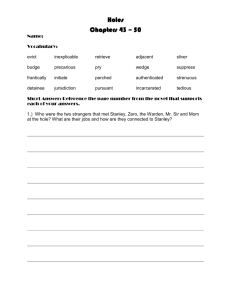

A.A. 2010-11 LINGUA INGLESE 1 LM session: Estivo (Giugno 2011) name: Gina Corcillo corso di laurea LLEA n.credits: 12 area of study: The Birthday Party Evaluation: You make a good attempt at interactional analysis here. Pinter looks simple but it is quite difficult to understand what is going on in his dialogues. You have shown that you can trace the relationships between characters through their narratives. story 1 – In this episode S fails to establish credibility because his story is incoherent.. Stanley’s hyperbole fails because he says “all over the world” and then “I once gave a concert”. He gives a detail “lower Edmonton” but the place is so insignificant that we cannot believe that he gave a concert there. As you rightly point out, the interaction between M and S is also incoherent because S never really answers Meg and Meg does not react to his story. Story 2 – excellent analysis here; the only problem is that G’s story is as implausible as Stanley’s (see my discussion of Uncle Barney below). As you say, there is a lot of tellability in the sotry but it is hard to believe and no interaction to confirm whether McCann believes it. Story 3 – yes, I agree with your analysis (my analysis is below) and your point about Goldberg controlling the conversation is quite right. This is very important in the context of the play. Story 4 – this story is like Goldberg’s other stories – high on tellability but totally implausible. The fact that the story is absurd makes Lulu’s comment that he is a good speaker even more absurd. But there is a sense in which G is a good speaker because he is able to control all the conversations he is involved in. He is discursively powerful and perhaps it is this that Lulu admires. You are right that there is more collaboration here than in Goldberg’s other stories (story 2, for example). Story 5 – yes another example of an autobiographical and self-aggrandising monologue with very little collaboration. Your conclusion is interesting. What Goldberg and Stanley have in common is that their stories are implausible. Yet despite the implausibility, Goldberg emerges as a powerful character. Everything revolves around Stanley yet he has no power. This suggest that power is about the ability to control a conversation, i.e. how you talk, rather than what you say. S and G both tell grandiose stories about themselves but it is G’s ability to control what others say which gives him authority in the house. FINAL MARK /10: 9 Uncle Barney Lack of collaboration in nostalgia is frequent in Pinter. In The Birthday Party Goldberg indulges in childhood reminiscences which are perplexing both to his listeners on stage and to the theatre audience: Little kiss Goldberg: … Anyway, I’d leave her with a little kiss on the cheek – I never took liberties – we weren’t like the young men these days in those days. We knew the meaning of respect. So I’d give her a peck and I’d bowl back home. Humming away I’d be, past the children’s playground. I’d tip my hat to the toddlers, give a helping hand to a couple of stray dogs, everything came natural. Uncle Barney Goldberg: You know one thing Uncle Barney taught me? Uncle Barney taught me that the word of a gentleman is enough. That’s why, when I had to go away on business I never carried any money. One of my sons used to come with me. He used to carry a few coppers. For a paper, perhaps, to see how the M.C.C. was getting on. Overseas. Otherwise my name was good. Besides, I was a very busy man. H. Pinter, The Birthday Party, Act 1 In these bizarre portraits of his adolescence (Little kiss) and fatherhood (Uncle Barney) Goldberg uses a mix of hyperbole (never took liberties, everything came natural, I never carried any money) and cliché (give her a peck, we knew the meaning of respect, take liberties, the word of a gentleman) to project an identity of himself as a gentleman with old-fashioned family values. However, these anecdotes about his past do not make these projected identities convincing. It is easy for a selfaggrandising story to come across as idle boasting (“talking the talk” in modern parlance) or as simply untrue and indeed Goldberg’s stories of his childhood seem almost comically implausible1. However, the main reason why these are not successful as nostalgic stories per se is because the listeners do not participate actively in them. The lack of response changes the effect of the narrative – a technique which Pinter uses in nostalgic stories in other plays. For example, in Act 6 of Betrayal Robert insists on how happy he had been when walking about on Torcello and that he had “wanted to stay there forever”; however, the lack of participation from Jerry makes this story seem a forlorn and sentimental one. In The Homecoming, Max’s nostalgic recollections of the family Christmas is delivered in total silence, as are his recollections of his father’s deathbed (Bowles 2009). In Old Times Anna’s monologue beginning Queuing all night, the rain, do you remember? is filled with nostalgia for the London of her youth. Her monologue concludes with three questions in quick succession … and does it still exist, I wonder? do you know? can you tell me?. After a slight pause Deeley replies We rarely get to London. This typically Pinteresque pattern of a lack of preface followed by a long monologue story followed by a pause is repeated when Anna comes up with a further long reminiscence of London beginning Don’t tell me you’ve forgotten our days at the Tate, which is received in total silence by Kate. The intensity of the descriptions, filled with chaotic 1 Billington (1996: 82) describes these speeches as “swathed in fake sentiment” but argues that the “private Edens” described by Pinter’s characters in this kind of speech are an indication of “how we all use a real or romanticised past to buttress the insecure present” (p.83). detail of their hypothetical life in London, without preface or response, has a typically disconcerting effect – a vivid and involving story which is unsupported in the interactional present. Concert (Meg and Goldberg) The final reference to Stanley’s identity in Act 1 takes place when Goldberg questions Meg about the occupants of the house. It prompts Meg to retell Stanley’s story of his concert in Lower Edmonton: Goldberg: Meg: Goldberg: Meg: Oh yes, a resident. What’s his name? Stanley Webber. Oh yes? Does he work here? He used to work. He used to be a pianist. In a concert party on the pier. Goldberg: Oh yes? On the pier, eh? Does he play a nice piano? Meg: Oh, lovely. (she sits at the table) He once gave a concert. Goldberg: Oh? Where? Meg (falteringly): In … a big hall. His father gave him champagne. But then they locked the place up and he couldn’t get out. The caretaker had gone home. So he had to wait until the morning before he could get out. (With confidence) They were very grateful (Pause) And then they all wanted to give him a tip. And so he took the tip. And then he got a fast train and he came down here. Goldberg: Really? Meg: Oh yes. Straight down. Meg’s story arises as an illustration of her claim that Stanley is a good piano player. In order to justify the claim Meg therefore needs to tell a convincing story. However, the narrative she produces is decidedly erratic. At the start she responds hesitantly with short, one-sentence answers (“Stanley Webber”; “He used to work. He used to be a pianist. In a concert party on the pier.”; “he once gave a concert”). She is described as speaking “falteringly”, she struggles to remember details and although she speaks “with confidence” about the reaction to Stanley (“they were grateful”), the pause that follows, which is attributable to Meg as she has not selected anyone to speak, chimes awkwardly with the confidence with which she has uttered her previous words. Meg’s story is part of a question-answer session in which the appropriacy of the story as a justification of Stanley being a good piano player is at stake. In this respect her account suffers from the same kind of incoherence as Stanley’s original one and achieves little in establishing his narrated identity as a concert pianist. It is unclear who “they” refers to or why they are “grateful”. As well as this lack of reference, Meg’s retelling is inaccurate. Her reconstruction involves picking up individual lexical items of Stanley’s story “concert … hall … father … champagne … caretaker … tip” and stringing them together to form a different story. Most retellings tend to reformulate much longer stretches of talk rather than individual items but Meg seems unable to remember longer stretches of discourse and relies solely, and comically, on lexical retrieval. Her transformation of the word “tip” is particularly revealing. She has interpreted Stanley’s use of the expression “take my tip” in its literal sense (“take some money”) not according to Stanley’s original meaning (“take a hint”). In interpreting an idiomatic expression in a literal sense. Meg is showing herself to be a character who finds it difficult to “do non-literal’ (Edwards: 2000). The position of Goldberg in this retelling is also significant. He is not an enthusiastic, participatory listener. Instead he elicits the story from Meg through his questions and then casts doubt on her account at the end. Even though he has not heard the story before, his scepticism of Meg’s retelling is justified and contributes to the impression he gives of a person who is controlling the conversation.