Understanding children`s perceptions of play

advertisement

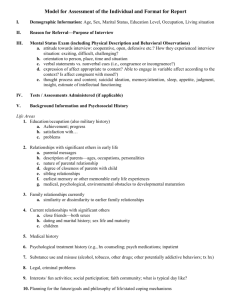

BERA Annual Conference 2002 Paper presentation Eliciting Children’s Perceptions of Play and Exploiting Playfulness to Maximise Learning in the Early Years Classroom Authors Justine Howard (University of Glamorgan) Wynford Bellin (University of Wales Cardiff) Val Rees (University of Wales College of Medicine) Correspondence details for first author Justine Howard Humanities and Social Science University of Glamorgan Pontypridd Mid Glamorgan CF37 1DL United Kingdom 01443 482358 (direct line) jlhoward@glam.ac.uk 1 BERA Annual Conference 2002 Paper presentation Eliciting Children’s Perceptions of Play and Exploiting Playfulness to Maximise Learning in the Early Years Classroom Abstract It is widely accepted that play makes a positive contribution to children’s development, particularly in the early years. Much of the developmental potential unique to play regards intrinsic or within child qualities such as motivation, enthusiasm, willingness to participate and self-preservation. Play is said to capture the attention of young children (Wood 1986), children are more enthusiastic about participation (King 1979) and are free from the fear of failure in the safe learning environment play provides (Moyles 1989). These qualities make an important contribution to learning outcomes. If we accept the importance of these qualities, then it would seem important to consider what children consider playful, particularly if we are to motivate children to learn through activities they themselves perceive to be play (Thomas 1999). This is particularly important when the act of play is distinguished from the internal qualities of playfulness. This paper summarises research that has focused on children’s perceptions of play. It suggests that children’s perceptions are related to experience. The characteristics used by children to define play are considered from an educational perspective, where practitioners have the opportunity to manipulate perceptions through the experiences they provide. The significance of understanding children’s perceptions for exploiting playfulness is discussed. 2 BERA Annual Conference 2002 Paper presentation Introduction A devotion to the study of children’s play has persisted for well over three decades. Researching this seemingly simple activity has proven to be a far from simple task. With its many forms and guises, defining play has and still appears to be, particularly problematic. Definitions have focused on categorisation, criteria or continuum. Whilst these have illuminated the complexity of play it is arguable as to whether or not they have drawn us any closer to reaching a definitive or generic definition (Wood and Attfield 1996). The benefits of providing an operational definition of play are also debated. From a research or psychological perspective such a definition may be useful to ensure that all researchers are talking about the same thing (Garvey 1990). From a pedagogical perspective however, all encompassing definitions may lead to straight-jacketing, where practitioners strive to provide classroom experiences which correspond to defining criteria (Wood and Attfield 1998). Activities which look like play. Difficulties in defining play appear to stem from a failure to distinguish the act of play from the construct of playfulness. The proposition that behavioural characteristics can be used to define play, as in criteria approaches (e.g. Krasnor and Pepler 1980; Rubin et al. 1983) leads to an either/or situation where an activity is categorised as play or not play, failing to consider varying degrees of play. Whilst continuum approaches have addressed this issue by suggesting that the more characteristics present, the more pure the play becomes (Pellegrini 1991), the use of defining characteristics suggests that these behaviours are specific to play and that playfulness cannot permeate any other activity. The limitations of defining play in this way are clear in the play-work dichotomy. If a distinction were drawn between play and playfulness, then this dichotomy would be less visible as feelings of playfulness could permeate both play and work. 3 BERA Annual Conference 2002 Paper presentation Guha (1988) raises the important issue of context, highlighting a further limitation of definitions that rely on characteristics. Whilst an activity may have the defining characteristics to achieve play status, the same activity on a different day or in a different location may take on board a different meaning to the player (the example provided by Guha is that of the professional footballer in comparison to the person who plays football on a Saturday afternoon). Guha suggests that in this situation the activity loses its play status as work like properties increase. However this is not to say that a sense of playfulness may not be retained by the player. It would appear then, that problems in defining play arise when play and playfulness are considered as one. Whilst certain activities may appear more play-like, we can never be sure whether the individual is feeling playful. Playfulness would appear to be an internalised construct that develops over time as a result of experience and interaction. We suggest that it is a failure to distinguish these two things that prevents the playfulness of play from being fully exploited in the early years. Play is an act defined by observable characteristics. The construct of playfulness comprises the internal qualities brought to the activity by the players themselves. Namely, how the player feels about the activity. So, whilst it may be possible to define or label certain activities as play in respect of the characteristics they display, the development that occurs during the activity is dependent on the perceptions of the player. It is this internal feeling of playfulness that can make such a valuable contribution to development, particularly in an educational context. On this premise, to understand the nature of playfulness, it is necessary to understand how players perceive their activities. 4 BERA Annual Conference 2002 Paper presentation Understanding children’s perceptions Wiltz and Klein (2001) maintain that whilst there has been a wealth of research directed towards understanding the influence of early child-care experiences on development, little is known about how children themselves perceive their environments. There is also minimal insight into the way in which children’s perceptions of play and subsequent concepts of playfulness develop, and are influenced by experience. Considering that much of the literature surrounding play comes from a developmental or educational perspective, in particular addressing how play contributes to child development, then it appears curious that such little time has been spent eliciting the perceptions of children themselves. As is stated by Woodhead and Faulkner (2000), much of the research into children’s play is observational, involving but not necessarily engaging children. Whilst observational techniques provide much information into the nature of children’s play, and allow us to make inferences about development and involvement in activities, they do not tell us about children’s perceptions and do not therefore allow us to make judgements about individual definitions of playfulness. This is particularly relevant where the distinction between the observable act of play is distinguished from playful intention. So why is it important to understand children’s perceptions of play and developing concept of playfulness? Rudduck, Day and Wallace (1997) argue that to improve school life, it is vital that children’s descriptions of their experiences are considered. There has been an increasing concern that the failure to actively engage children in research designed to elicit their own perceptions, has led to suppositions about children’s experiences. For example, whilst the introduction of circle time may be seen as a positive experience for early years children, research has demonstrated that children’s enjoyment of this activity may be minimal. Wiltz and Klein (2001) found that children aged 48-70 months described circle time in a negative way, regardless of 5 BERA Annual Conference 2002 Paper presentation whether they were in high or low quality classrooms. Readdick and Chapman (2000) propose that without asking children about classroom practices, observations of behaviour management strategies such as ‘time-out’ may lead to speculation that they are hurtful or humiliating. Such over simplification is confirmed by Wiltz and Klein (2001) who found that children’s perceptions of time out are far more complex than such speculation would suggest. When children were asked about things they didn’t like about school, time-out was reported infrequently. However when asked what made them sad, angry or mad at school, time-out was the second most frequently occurring response. There were also differences in perceptions of time-out according to classroom experience and the way that this management technique was used. Time-out appeared to work best where children experienced it infrequently. Consequently the occasions when it was used appeared memorable. Where time-out was a principal means of class control, children appeared to perceive it as commonplace or had learned to ignore it. The fact that children discussed time-out, regardless of whether or not they had experienced it, suggests that the children had developed a script about its meaning and consequence. Understanding children’s perceptions of time-out can therefore make an important contribution to classroom practice. Studies such as this also reveal how children’s understandings about the world around them are not only based on concrete experiences as in cognitive constructivism, but that scripts of possible experiences are also developed through interaction with others as in social constructivism. 6 BERA Annual Conference 2002 Paper presentation Understanding children’s perceptions of play As is indicated by Figure 1., the developmental potential of play can be maximised where children perceive the activity as play and subsequently approach it in a playful manner. It is therefore useful to understand how children perceive play and the ways in which they feel it differs from other activities. Figure 1. Utilising playfulness to maximise developmental potential Player does not perceive the activity as play and consequently does not take a playful approach. Intrinsic qualities are those for ‘serious activity’. If approached nonplayfully the developmental potential of the activity may not be maximised THE OPPORTUNITY Physical Social Cognitive Emotional Language Player perceives the activity as play and consequently takes a playful approach. Intrinsic qualities such as motivation, enthusiasm, freedom from fear, willingness and engagement are harnessed. When approached playfully, the developmental potential of the activity can be maximised There are few studies that have investigated children’s perceptions of play (Table 1 summarises these studies). Studies that have elicited such data challenge earlier theoretical perspectives such as those of Isaacs (1932) and Manning and Sharp (1977), who proposed that children were unable to distinguish play from other activities. Studies show that children are able to distinguish play from other activities and refer to certain indicative characteristics such as play being fun, noisy and spontaneous, occurring on the floor rather than at a table and being free from rules (Fein 1985; King 1979). 7 BERA Annual Conference 2002 Paper presentation The use of such characteristics has been affirmed by Wiltz and Klein (2001) who also found that regardless of classroom quality, self-selection and choice are important determinants of play activity. Wiltz and Klein (2001) also indicate that self-selection and choice can override activity type in the categorisation of an activity, for example a teacher-directed colouring task could be categorised as work whereas a self-initiated colouring activity be regarded as play. This again highlights the need to separate the act of play from the feelings of playfulness brought to the activity by the player themselves, as what looks like play from the outside may not be approached in a playful manner. Further limitations of assuming a common script between the outsider perceptions and the perceptions of the player are highlighted by Rothlein and Brett (1987) who found a difference between what children considered to be their favourite play activities (and therefore approached more enthusiastically) and what teachers thought they found most enjoyable. Whilst teachers thought children most enjoyed block play, children themselves were most enthusiastic about participation in outdoor play. Karrby (1989) suggests that children’s perceptions of play are related to classroom experience. In this study children from a play-oriented environment appeared to have a more diverse perception of learning, where opportunities to learn were described in a number of classroom activities including play. Children in a more teacher-directed and structured setting separated play from learning, describing teacher directed activities as learning and self-initiated activity as play and consequently not learning. Howard (in press) also suggests that children’s perceptions of play, work and learning are influenced by early classroom experience. The Activity Apperception Story Procedure (a photographic sorting task) indicated that children responded to cues when making decisions about play, work and learning, namely space and constraint, positive affect, the nature of the activity and teacher presence. Dependent on their classroom experience (primary 8 BERA Annual Conference 2002 Paper presentation class or day nursery), children also attended to school context, free choice and skill development. This study also demonstrated how the cues or characteristics used to define activities became more complex with age, suggesting the elaboration of schema with time and experience. Table 1 Summarising research into children’s perceptions of play Rothlein and Brett Karrby (1989) Keating et al (2000) (1987) Interview Interview Interview 103 children 2-6 years 15 children 5-6 years 10 classes 5-6 years Pre-schools and child 2 pre-school sites with 10 reception classes care centres (USA) differing provision (UK) free v directed (SWEDEN) Play Outdoors Games with people Art and Craft Role play Positive affect Not play TV Sleep/eat Colouring Doing nothing Play related to specific activities. Adults and children not always perceive activities in a similar way. Adults dichotomise play and learning. Play Pretence Role play Themes Rules Not play Construction Mastery Learning Ability Practise Books Being taught Skills Sitting Play meaningful, children found it easier to reflect on play than learning. Adult observations and child reports often not congruent. Free environment children did not separate play from learning. Play Choice Role play Art and Craft Colouring Not important Dichotomous to work No teacher involved Work Having to Occurs at school Important Involves teacher Play subordinate to work. No adult involvement in play. Play self controlled and free whereas work enforced and compulsory. Attuned to school context. Howard (in press) AASP 111 children 3-6 years 6 early years sites with differing provision – public/private, day nursery/primary classes (UK) Play, work and learning characterised by; Space and constraint Teacher presence Positive affect School context Nature of the activity Skill development Personal control Play/not learning and work/learning (+) correlated. Children used cues to categorise activities. Choices related to experience. Child initiated environment promotes less dichotomy and separation of play and learning. Curriculum emphasis influenced children’s use of skill/ school context cue. 9 BERA Annual Conference 2002 Paper presentation Utilising feelings of playfulness The value of play as a learning medium in relation to enthusiasm, motivation, creativity and willingness to participate (King 1979; Moyles 1989), and the resulting social, cognitive and emotional development (e.g. Sylva et al. 1980; Saracho 1991; Saracho and Spodek 1998) is inextricably linked to the way in which the activity is perceived by the player. When considering the benefits of play within early years education, the perspective of the child is of great importance. This paper has illuminated how young children are able to distinguish play from work and learning from not learning. Previous research, has suggested that children are more enthusiastic about involvement in play and even describe negative classroom experiences as being those which interrupt play activity, for example participation in circle or nap time (Wiltz and Klein 2001). Therefore rather than concentrating wholeheartedly on the task in hand (Manning and Sharp 1977) children so appear to distinguish activities and may approach them with a specific mind set. Playfulness is an internal state comprising the internal qualities that children bring to an activity. It is therefore important to understand what children believe to be play, how such perceptions may have developed and how feelings of playfulness can be evoked. This paper has revealed how children attend to certain cues when making play, work and learning judgements. The AASP stimuli (Howard in press) revealed how they refer to space and constraint (where an activity takes place), teacher presence, positive affect (whether the activity is fun) and the nature of the activity (academic versus play materials). In justifying their play, work and learning judgements children also used a range of other cues, for example the educational context (because the activity is occurring in school), skill development (getting better at something or 10 BERA Annual Conference 2002 Paper presentation practising it), pretence (play because its pretending) and personal control (being able to choose). The use of these cues was related to the type of educational provision, with marked differences apparent between children attending primary classes and those in day nurseries. Children in primary schools appeared far more aware of skill development, attainment and play being available as choosing time after work. Children in day nurseries made far more learning judgements and were more likely to see learning in a range of classroom situations including play. This is consistent with the findings of Karrby (1989) who found that children in a more structured setting dichotomised play and work more readily and did not perceive play as learning, In contrast, children in the play oriented environment frequently described learning through play. How are practitioners empowered? Through understanding children’s perceptions and their use of environmental cues, practitioners may be empowered to exploit playfulness (Table 2). Table 2 Using children’s perceptions to exploit playfulness Space and constraint Teacher presence Positive affect Skill development Choice and control In a structured setting children often learn that work occurs at a table and play in any location. Where such a boundary does not exist, children are more able to feel playful in a range of activities. When children are unused to adult involvement in play they often use this as a defining characteristic. Consequently an activity loses its play status when an adult is present. Use of this cue can be prevented if children frequently experience adult involvement in all classroom activities. Encouraging positive affect in a range of classroom activities can maximise learning by evoking a playful approach. Increased emphasis on skill development and attainment reduces feelings of playfulness. It is therefore important to emphasise process over product. Children may approach activities more playfully when they perceive choice and control. 11 BERA Annual Conference 2002 Paper presentation Findings from research into children’s perceptions of play support the proposition that children use environmental and emotional cues to form schema for action and events (e.g. Rogoff 1990). Children use both concrete experiences (as in what opportunities have been provided for them) and the nature of classroom interactions (as in whether the teacher has been involved in their play) to form their perceptions of play, work and learning. Both of these can be manipulated by practitioners to exploit feelings of playfulness. Figure 2 demonstrates the process by which children’s perceptions might develop and then be subsequently evoked. Fig (2) dynamic model Children’s perceptions influenced by experience Practitioner / School Structure environment Playful approach Make decisions about interaction Children’s perceptions influenced by experience - making sense of the environment Nonplayful approach Presentation of activity children look for cue match and make decision about approach Whilst generic definitions of play may cause straightjacketing as practitioners strive to provide activities which correspond to defining characteristics, knowledge about children’s perceptions of play is empowering. If we understand the kinds of things that lead children to categorise an activity as play, then we are able to inject feelings of playfulness into a number of classroom activities. For example, if children use teacher presence when making judgements about play, then they are less likely to approach an activity playfully when there is teacher involvement. Children who are used to teacher involvement in play activity are less likely to use this as a defining feature and so will be more likely to accept adult involvement and retain a sense of 12 BERA Annual Conference 2002 Paper presentation playfulness. This is important if practitioners are to be accepted as ‘committed co-players’ to facilitate learning (Rich 2002). Understanding children’s perceptions of play and subsequent playful approach enables playfulness to be harnessed and injected into a number of classroom activities. This enables practitioners to align developmental and educational objectives through the exploitation of children’s natural propensity to play. References Fein, G. (1985) Learning in play; surface of thinking and feeling. In J.L.Frost and S.Sunderlin (Eds) When children play. Wheaton, Association for Childhood Education International. Garvey, C. (1990) Play (enlarged edition). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. Guha, M. (1988) Play in School, in G. Blenkin and A. Kelly, Early Childhood Education. London; Paul Chapman. Howard, J. (in press) Eliciting Young Children’s Perceptions of Play, Work and Learning Using the Activity Apperception Story Procedure. Early Child Development and Care. Isaacs, S. (1932) The Nursery Years. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. Karrby, G. (1989) Children’s conceptions of their own play. International Journal of Early Childhood Education, 21(2), 49-54. King, R. (1978) All Things Bright and Beautiful ? A sociological study of infants classrooms. Bath: Wiley. King, R. (1979) Play: The Kindergartners Perspective. Elementary School Journal, 80(2), 81-87. Krasnor, L.R. and Pepler, D.J. (1980) The study of children’s play : some suggested future directions, in Rubin, K. (Ed) Children’s Play, Jossey Bass, San Fransisco. Manning, K. and Sharp, A. (1977) Structuring play in the early years at school. London: Ward Lock Associates. Moyles, J. (1989) Just Playing : the role and status of play in early childhood education. London: Open University Press. Pellegrini, A. D. (1991) Applied Child Study : a developmental approach. NJ: Erlbaum Associates. Readdick, C. and Chapman, P. (2000) Young children’s perceptions of time out. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 15(1), 81-87. Rich, D. (2002) Catching children’s stories. Early Education 36, p.6. 13 BERA Annual Conference 2002 Paper presentation Rogoff, B. (1990) Apprenticeship in Thinking ; Cognitive Development in Social Context. New York: Oxford University Press. Rothlein, L. and Brett, A. (1987) Children’s, Teachers and Parents Perceptions of Play. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 2(1), 45-53. Rubin, K. H., Fein, G. G. and Vandenberg, B. (1983) Play, in Mussen, P. H. and Hetherington, E. M. (Eds) Handbook of Child Psychology (4th Ed) vol. 4, Basel, S. Karger. Rudduck, J., Day, J. and Wallace, G. (1997) Students perspectives on school improvement. Yearbook, Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 1997, 73-91. Saracho, O. (1991) Educational play in early childhood, Early Child Development and Care, Vol. 66 pp 45 - 64. Saracho, O. and Spodek, B. (1998) A Historical Overview of Theories of Play. In Saracho and Spodek (Eds) Multiple Perspectives on Play in Early Childhood Education. New York: New York Press. Sylva, K., Roy, C., and Painter, M. (1980) Childwatching at Playgroup and Nursery School. London: Grant McIntyre. Thomas, E. (1999) In Defence of Play. Article published in the Times Educational Supplement, July 1999. Wiltz, N. and Klein, E. (2001) What do you care? Children’s perceptions of high and low quality classrooms. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 16 (2001), 209-236. Wood, D. (1986) Aspects of teaching and learning. In M. Richards and P. Light (eds) Children of Social Worlds. Cambridge: Polity Press. Wood, E. and Attfield, J. (1996) Play, Learning and the Early Childhood Curriculum, London: Paul Chapman. Woodhead, M. and Faulkner, D. (2000) Subjects, Objects or Participants; Dilemmas of Psychological Research with Children. In P. Christensen and A. James (Eds) Research with Children. London: Falmer Press. 14