A syntax for cardinal expressions in Greek

advertisement

A syntax for cardinal expressions in Greek

Melita Stavrou and Arhonto Terzi

Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and Technological Educational Institute of Patras

staurou@lit.auth.gr, aterzi@teipat.gr

Athens reading group in linguistics

December 2, 2011

.

1.

Introduction

Aim

Propose a syntax for Greek cardinals, both simplex (ena puli 'one bird') and complex (tris xiljades

ergates 'three thousand workers').

Claims

▪ Cardinals in Greek share properties with:

a) adjectives: they belong to the modificatory system of the noun and agree in all phi-features with it.

b) vague weak quantifiers: crucially, they license articleless subjects.

▪ Cardinals, alongside weak quantity denoting quantifiers (QWQs), are quantificational elements

related to Number Phrase.

a) when the cardinal construction is indefinite, D is empty and is interpreted under existential closure;

the existential quantifier in the empty D is licensed by the cardinals in NumP.

b) when the cardinal construction is definite, D is realized by the definite article and the existential

interpretation is blocked.

▪ Complex cardinals and complex numerals with set interpretation have a different syntactic structure.

despite the fact that they are morphologically identical.

2.

The facts

2.1 Simplex cardinals

Simplex cardinals are either morphologically underived, (1), or derived, hence, bi-morphemic, (2):

‘one book’

‘six books’

‘a hundred books’

‘a thousand books’ (and see (4) below).

(1)

a.

b.

c.

d.

ena vivlio

eksi vivlia

ekato vivlia

xilja vivlia

(2)

a.

Agorasa tetrakosjes efimeridhes.

bought-1s four-hundred newspapers

‘I bought four hundred newspapers.’

Plirosa eksakosja evro gi afto to palto.

paid-1s six-hundred euros for this the coat

‘I paid six hundred euros for this coat.’

b.

2.2 Complex cardinals

Complex cardinals consist of two (or more) words. There are two types: additives, (3), and

multiplicatives, (4). We only discuss the latter here.

(3)

a.

b.

(4)

a.

b.

ikosi pende vivlia

twenty five books

ekaton trianda okto molivia

hundred thirty eight pencils

dio xiljadhes vivlia

two thousand books

tria ekatomiria anthropi

three million people

Xiljadhes and ekatomiria are nouns morphologically, a fact we take into consideration in our analysis.

Greek differs from English in this respect: *two thousands books and *three millions people.

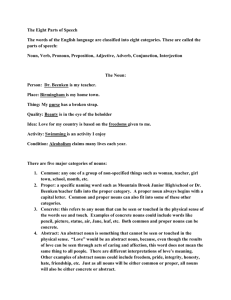

Figure 1

Cardinals

Simplex

(one word)

mono-morphemic

<underived>

eksi

(6)

low

High cardinals

Simplex:

Complex:

bi-morphemic

<derived>

eksakosja

(600)

high

Complex

(two words)

eksi xiljadhes

(6.000)

eksi (six)+-kosja

(hundred) bi-morphemic

eksi (six) + xiljadhes (thousand) two-word

The conceptual structure of both subtypes of high cardinals is essentially the same: both involve an ‘

M’ element as their second part (Hurford (1987: 242-245), namely, a higher numerical expression that

combines with a smaller one to give a complex cardinal. Hence, they both comply with Hurford’s

Packing Strategy.1

2.3 Nominal numerical expressions

Greek has another type of numerals, which look like cardinals but they are not: rather, they count sets

of entities. They have been discussed by Stavrou and Terzi (2008).

1

According to Hurford (op.cit.) there is a Universal Constraint on complex numerals, which he calls The Packing

Strategy. This states that ‘when two numbers are added or multiplied to express a higher number, the resulting construction

is usually markedly unbalanced, in the sense that one of the numbers is much greater than the other, and languages tend

strongly to maximize this kind of imbalance.” In our case, both –kosja and xilja are the highest numbers in their containing

words (cf. English –ty, hundred, thousand, million.

2

(5)

a.

b.

c.

mia eksadha vivlia

tesseris decadhes molivia

tris xiljadhes vivlia

‘a set of six books’

‘four sets of ten pencils’

‘three thousand books’, etc.

These numerical expressions, (5)-(6), are also syntactically complex, but differ from those in (4a) amd

(7), which count items rather than sets of items:

(6)

a.

b.

(7)

Agorase tesseris ekatondadhes vivlia.

bought-3s four

hundred-adhes books

‘She bought four sets/boxes/etc. of a hundred books.’

Efere

tris eksadhes bires.

brought-3s three six-adhes beers

‘She brought three (packs of) six beers.’

Katanalosan tris xiljadhes

bires sto gamilio parti.

consumed-3p three thousand-adhes beers at-the wedding party

‘They consumed three thousand beers at the wedding reception.’

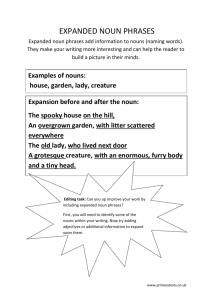

Figure 2 Complementarity in the interpretation of numerical nouns and (complex) cardinals

Cardinals

Numerical Nouns

3

Tria

Cardinal

Interpretation

No

Set

Interpretation

Triadha

4

Tesera

No

Tetradha

5

Pende

No

Pendadha

…

…

….

Ikosi

No

Ikosadha

…

…

100

Ekato

No

(mia) ekantondadha

200

Diakosia

No

dio ekatondadhes

300

Triakosia

No

tris ekatondadhes

400

Tetrakosia

No

teseris ekatondadhes

…

…

…

900

Eniakosia

No

enea ekatondadhes

1.000

Xilja

No

?(mia) xiljadha

2.000

dio xiljadhes

dio xiljadhes

No

3.000

tris xiljadhes

tris xiljadhes

No

…

…

…

…

9.000

enea xiljadhes

enea xiljadhes

No

10.000

deka xiljadhes

deka xiljadhes

No

…

…

…

…

1.000.000

ena ekatomirio

ena ekatomirio

No

20

3

The distribution of numerals with set interpretation is not random. The existence of a simplex cardinal

allows for the set interpretation of the corresponding two-word numerical expression, in a pattern that

is akin to other patterns of the analytic vs. synthetic alternation (cf. Embick 2007).

Question:

Do complex numerals, as in (5) and (6), and complex cardinals, as in (4a) and (7), have

the same syntax?

3.

Setting the scene

3.1 The agreement patterns: evidence for syntactic cardinals as modifiers/adjectives

When used outside a nominal, e.g., in counting (ena, dio, tria, tessera,...) cardinals are invariable (e.g.

they are realized as stems/roots).

Once inside the noun phrase Greek simplex cardinals agree in phi-features with the lexical noun and all

the modifiers that may appear in the extended nominal projection, including articles.

(8)

(tus)

(the.pl.masc.acc)

‘(the) four men’

(9)

a.

b.

tesseris

andres

four.pl.masc/fem.acc/nom men.pl.masc.acc

(i)

tetrakosjes

ginekes

(the.pl.masc/fem.nom) four-hundred.pl.fem.nom woman.pl.fem.nom

‘(the) four hundred women’

(ta)

tetrakosja

pedja.

(the.pl.neut.nom)

fourhundred.pl.neu.nom child.pl.neu.nom

‘(the) four hundred children’

There is an exception: complex cardinals (10a-b) present an issue of gender mismatch with the lexical

noun. The mismatch is due to the fact that the second word of the complex cardinal, i.e., xiljadha

‘thousand’, is a noun, and as such it comes with its own gender feature (i.e., feminine).

The preceding simplex cardinal agrees with the numerical noun.

(10)

a.

b.

(ta)

tris

xiljadhes

vivlia

(the.pl.neu.nom/acc) three.pl.fem.nom/acc thousand. pl.fem.nom/acc

book.pl.neu.nom/acc

(i)

tris

xiljadhes

anthropi

(the.pl.masc.nom) three.pl.fem.nom/acc thousand.pl.fem.nom

person.pl.masc.nom

A similar gender mismatch arises when the complex cardinal involves ekatomirio

‘milion’, which is a neuter noun, (11).

(11)

a.

(ta)

tria

ekatomiria

ipografes

(the.pl.neu.nom) three.pl.neu.nom/acc million.pl.neu.nom

signature.pl.fem.nom/acc

b.

(ta)

tria

ekatomiria

anthropi

(the.pl.neu.nom) three.pl.neu.nom/acc million.pl.neu.nom

person.pl.masc.nom

4

Despite the above mismatch, Greek cardinals do not appear to assign case to the associated nouns

(e.g. genitive), unlike cardinal numerals in Russian (and in other Slavic languages, for instance),

discussed by Ionin and Matushansky 2006; Rutkowski 2008, or Standard Arabic (Shlonsky 2004).

For this reason we cannot consider them as (case-assigning) heads (Q/D), but more like adjectives.

3.2 Further similarities between cardinals and adjectives

Like adjectives, cardinals can license nominal ellipsis, (13), can be used predicatively, (14), can be

substantivized (or nominalized) in the presence of the definite article, (15), and they follow pronominal

determiners in appositive-like constructions, (16):

(13)

I Maria agorase tria/endiaferonta vivlia, eno i Eleni xilja/aniara vivlia.

the M. bought three /interesting books while the Eleni thousand/boring books

‘Mary bought three interesting books while Eleni a thousand/boring ones.’

(14)

To potiria sto

dulapi

ine eksi/eksakosia/orea/krystalina.

the glasses in-the cupboard are six/six-hundred/beautiful/crystal

‘The glasses in the cupboard are six/six hundred/beautiful/crystal.’

(15)

I pende/diakosji/psili prokalesan episodia.

the five/two-hundred/tall caused incidents

‘The five/two hundred/tall caused trouble.’

(16)

Emis i tris/psili.

we the three/tall

‘we three/tall’

3.3 Differences between cardinals and adjectives

However, cardinal constructions also differ from nominals modified by adjectives: (17) shows that

cardinal expressions, unlike noun phrases with adjectives, achieve subjecthood even without an article.

(17b) in particular shows that a postverbal bare nominal is slightly better than a preverbal one, as

predicted by Longobardi (1994). (18) shows that cardinals achieve argumenthood even with an omitted

noun, something adjectives fail to do.

Alternatively, cardinal expressions may be substantivized – i.e., appear as arguments when the

head noun is omitted (see Giannakidou and Stavrou 1997 for conditions on nominal ellipsis),

something that plain adjectives cannot do, (18). Furthermore they can head the partitive construction,

(19), and allow for ‘split topicalization’, (20), unlike adjectives:

(17)

a.

b.

(18)

Tris/*eksipni fitites parusiasan to arthro.

three/*clever students presented the article

Irthan tris/??eksipni fitites.

came three/??clever students

Sinandisa tris/diakosjus/*omorfus.

met-1s three/two-hundred/handsome

‘I met three/two hundred/*handsome.’

5

(19)

Eksi/pendakosji/*psili apo tus diadilotes prokalesan episodia.

six/five-hundred/tall of the demonstrators caused trouble

‘Six/five hundred/*tall of the demonstrators caused trouble.’

(20)

Vivlia agorasa epta/eptakosja/dio xiljadhes/*endiaferonda.

books bought-1s seven/seven-hundred/two thousand/*interesting

‘Books I bought seven/seven hundred/two thousand/*interesting.’

In the light of the facts in this section, cardinals cannot be easily collapsed with adjectives. Instead,

(17)-(20) point towards their quantificational nature.

3.4

Cardinals and (weak) Quantifiers

Two interrelated facts:

(a) Cardinal constructions are encountered as arguments without any article.

Question:

Should cardinals be treated on a par with bare nominals (bare plurals and mass nouns)?

Bare nominals are assumed to be semantically predicates which are turned into arguments if a D is

added in the structure. They are banned from argument positions, except from plurals and mass nouns

(Longobardi 1994 and subsequent work, among many others).

Even plurals and mass nouns display a parametrized constraint on lexical government, in the

sense that while they are accepted in object position, they cannot appear as subjects (Longobardi,

op.cit.) in certain languages (e.g., Italian).

Unlike bare noun phrases with adjectives, see section 3.3, bare noun phrases with cardinals are licensed

as arguments, even as subjects, (21). Moreover, they can appear as arguments without a following

noun, (22), they can head the partitive construction, (23), and allow for split topicalization, (24).

In all these properties they pattern with quantity denoting weak quantifiers (QWQs):

(21)

a.

b.

Tris/ligi fitites parusiasan to arthro. (cf. (17))

three/few students presented the article

Irthan tris/ligi fitites.

came three/few students

(22)

Sinandisa tris/merikus/ligus. (cf. (18))

met-1s

three/several/few

‘I met three/several/few.’

(23)

Tris /meriki/ligi apo tus diadilotes prokalesan episodia. (cf. (19))

three/several/few of the demonstrators caused trouble

‘Three/several/few of the demonstrators caused trouble.’

(24)

Vivlia agorasa merika/liga/deka. (cf. (20))

books bought-1s several/few/ten

‘Books I bought several/few/ten.’2

2

Wiese 2003 makes the same observation with regard to the similarities between cardinal expressions and weak

quantifiers like many, few, etc.

6

(b) Bare nominals get an existential interpretation as default.

Cardinals (and QWQs) also have existential force, hence, they can appear in existential there-sentences

(Milsark 1977; Lyons 1999; Ionin and Matushansky 2006: 6-7 and references therein, among many

others). Cardinals behave like indefinites in this respect.

(25)

a.

b.

{Tria, arketa} pulakia kathondan

stu Diaku to taburi. (folk song)

{three, several} birdies were sitting on.the Diakos rampant

∃x [(three/several birdies) (x) & (sit…) (x)]

In semantic terms, a common analysis to account for existential force is to invoke some type-shifting

operation which raises the predicative interpretation to the argument interpretation (Landman 2003

with reference to Partee 1987). Longobardi (1994) assumes an empty D above the predicate nominal

which imparts existential force to the nominal.

Question:

Why are cardinals different from bare nouns with adjectives in this respect?

4. A syntax for indefinite cardinal constructions.

In this section we are concerned with proposing a structure for indefinite cardinals, which will be able

to take into account their existential force, their argument status (even when they are not introduced by

an over determiner) and their morphosyntactic properties, in particular, the agreement in phi-features

with the noun.

4.1

Some previous accounts

Semantic

a) determiners (type <<e,t>, <<e,t>, t>> (Montague 1973; Partee 1987),

b) predicates (type <e,t>),

c) modifiers (type <e,t>, <e,t>) (Verkuyl 1981; Link 1987; Landman 2003; Ionin & Matushansky 2006)

Syntactic

Jackendoff 1977 and Selkirk 1977: cardinals are essentially quantifiers, both located in spec,N’’ (under

their ‘three-level hypothesis’).

Loebel 1990, 1993: Qs and cardinals are situated in the specifier position of the category QP which

comes between D and NP in the extended nominal projection.

Giusti 1991, 1997, and Cardinaletti and Giusti 2005 lump together all Qs and cardinals and, in their QP

hypothesis, they consider Qs to project their own category at the top of the nominal projection, namely,

above DP, which is thus their selected complement.

Cornilescu 1993 assigns cardinals dual status; when they are heads (licensing the partitive construction

or standing on their own) they are under Q, at high level of the DP. When they are adjectival, occurring

before nouns and acting as noun modifiers, they are generated lower, probably immediately lower than

demonstratives which they linearly follow,

Corver and Zwarts 2006, propose the structure in (28a) and (28b) for simplex and prepositional

cardinals respectively. (See also Barbiers 2007 for more on Dutch numerals).

(26)

(27)

Rond de twintig gasten kwamen er op het feest.

round the twenty guests came there at the party

‘Around twenty guests came to the party.’

a.

can be complements of Ps

7

(28)

b.

c.

d.

a.

b.

combine with quantificational determiners

have nominal distribution in idiomatic expressions.

complement pronominal determiners

[NumP [NP 20] [Num’ NUM [NP kinderen]]]

[NumP [PP rond de 20] [Num’ NUM [NP kinderen]]]

‘(around) 20 children’

Corver and Zwarts 2006: 51.

What is at stake in the syntactic literature is whether or not cardinals are heads (in particular D/Q

heads, something that would straightforwardly account for their argument licensing capacity), or

phrasal, hence, specifiers.

The former approach can be matched with the semantic determiner theory of cardinals, the second with

the adjectival (Landman 2003) or modifier theory (Ionin and Matushansky 2006), (29):

(29)

NP (<et>)

card (<et et>)

NP (<et>)

card (<et et>)

NP (<et>)

Our proposal somehow combines elements from both approaches: we hold that cardinals are specifiers

of NumP, a category that hosts the features of singularity and plurality and thus regulates the

extensivity (extension) of the noun phrase. On the other hand, NumP is dominated by D.

4.2

Cardinals are not Ds

As pointed out already, section 3.4, noun phrases with no article, but with a cardinal (or QWQ), may

stand as arguments/subjects. This fact strongly suggests that cardinals are quite different from

adjectival modifiers (cf. again the data in (17)-(20)).

But then are cardinals realizations of D, hence cardinal expressions can be arguments?

The popular theory of Generalized Quantifiers takes cardinals and quantificational elements more

generally to be Q determiners (Montague 1973; Barwise and Cooper 1981). According to the GQ

theory, determiners in natural language combine with a nominal (type <et>) to produce a type of

quantificational nominal with argument status, known as the “generalized quantifier” (GQ; type <<et>

t>). QP denotes a GQ.

GQs can be strong (every, most), or weak, like some, few, three, many, etc.

In this theory, cardinals are standardly taken to be, syntactically and semantically, realizations of the Q

head which then takes the nominal phrase as its complement. Giannakidou 2004, 2011 and Etxeberria

and Giannakidou 2010 claim that strong quantifiers are Q heads in Greek and in Basque and they take

the NP as their argument.

The clearest argument as to why cardinals (or QWQs for that matter) should not be considered as D

heads comes from the fact that they can be preceded by D. Consider (30) and (31):

(30)

a.

the many/three boys

8

(31)

b.

the many/three clever young boys

a.

Ta dio aftokinita tha forologunte.

the two cars

will be.taxed.3pl

‘The two cars will be taxed.’

O enas fititis na kathisi stin akri, i dio (ali) brosta.

the one student SUBJ sit at.the side, the two (others) at the front

‘One of the students must sit by the side, the (other) two at the front.’

b.

Could it be that the article forms a complex head with the cardinal, along the lines of Giannakidou and

Etxeberria and Giannakidou (op.cit.)? This is unlikely given that between the article and the cardinal

certain items may appear, such as degree/approximative words, and also certain adjectives, i.e., alos

'other', (32). This is not the case with strong Qs, where nothing can go between the article and the Q,

(33). For a similar objection see also Landman 2003:217.

(32)

a.

b.

(33)

a.

b.

I tris fitites..

the three student

I ali tris fitites

the other three students

O kathe fititis …

the every student

*O sxedon kathe fititis

the almost every student

Moreover, cardinals (just as demonstratives, which according to many analyses are specifiers) can

stand on their own, by contrast to deteminers.

(34)

a.

b.

Sinandisa tris/diakosjus.

met-1s three/two-hundred.

‘I met three/two hundred.’

*Sinandisa ton/tin

met-1s

the-masc/the fem

We conclude that cardinals should not be considered as (D) heads.3 In this we differ from Cardinaletti

and Giusti (2005), see below.

4.3 Definite cardinal constructions

Cardinaletti and Giusti 2005 hold that definite and indefinite cardinal constructions, (35a) vs. (35b), are

structurally different, (35b) vs. (35d).

(35)

3

a.

b.

many/three boys

the many/three clever young boys

Ionin and Matushansky dismiss the cardinal-as-Determiner hypothesis also because determiners are not recursive

whereas cardinals are.

9

In (35a)=(35c) cardinals are like quantifiers, while in (35b)=(35d) they are what they call quantity

adjectives, occupying a lower adjectival position.

c.

d.

[QP many/three] [NP boys]]]

<QP: Quantifier Phrase>

[DP [the] [QAP [many/three] [NP boys]]] <QAP: Quantity Adjective Phrase>

We differ from Cardinaletti and Giusti (ibid.) in that we do not assign cardinals (and QWQs for that

matter) dual status. We take the topmost DP to carry different feature specifications in each case. In the

indefinite case, the DP is headed by a lexically empty D, while in the definite it is headed by the

definite article.

The structure of a definite noun phrase is a DP, headed by a D [def]. We take [def] to be the

marked feature, while absence of definiteness is related to absence of a feature ([]).

(36)

DP

ru

D

[def]

i

the

NumP

ri

dhiakosji

Num’

two-hundred

ru

Num

[pl]

FP

tu

F’

tu

AP

aganaktismeni

indignant

F

NP

diadilotes

demonstrators

We consider the cardinal to occupy the specifier of NumP, the category that is standardly taken to be

the locus of plurality.

4.4 The structure for Greek simplex cardinals

Two main assumptions:

(a) when no article or other determiner precedes the cardinal, D does not need to bear a (in)definiteness

feature. This is the default case, which holds whenever [def] is absent.

(b) cardinals are again in Spec, NumP.

(37)

a.

b.

c.

d.

O Iraklis Puaro agorase kenurgio pukamiso.

the Iraklis Puaro bought.3sg new shirt

'Hercules Poirot bough a new shirt.'

Vrikes isitirio?

found.2sg ticket?

'Did you find a ticket?'

Pao na agoraso efimerida.

go.1sg SUBJ buy.1sg newspaper

‘I am going to buy a paper.’

Grafi me ekseretiko talento.

10

e.

write.3sg with excellent talent

*Isitirio iparxi pano sto trapezi.

ticket is on.the table

*'Ticket there is on the table.'

The omissibility of the indefinite article with singular count nouns in Greek has been studied primarily

by Marinis 2005 and Sioupi 2001.

(37) shows that the indefinite article is not always required in indefinite noun phrases, and,

consequently, one could argue, along the lines of Lyons (1999, op.cit), that the indefinite article only

encodes indefiniteness, but does not mark it, indefiniteness itself being marked by the absence of the

definite determiner.

We therefore assume that in indefinite cardinals, D lacks the [def] feature and as a consequence D is not

pronounced; no article precedes the cardinal.

Turning to the association of cardinals with NumP, this has been assumed by a number of

researchers (Corver and Zwarts and references cited there; Rutkowski, a.o.).4

Hence, (38) is the structure we propose for indefinite cardinal constructions:

(38)

[DP D [NumP [Num’ {enas, tris} [ Num[+/-PL] [NP djadilot is/-es]]]

one, three

demonstrator /s

Where D is [], i.e., it lacks the definiteness feature, we assume that the numeral in Spec, NumP, by

virtue of its quantificational/cardinal nature, introduces an existential operator in the D position, which

imparts existential force to the DP. his view, which implies the presence of a null D, explains also the

argument status of cardinal containing nominals.

5.

The structure of Greek complex numerals

5.1 Numerical Nouns with set interpretation

Two-word multiplicative numerals smaller than 1000 do not have a cardinal interpretation. Instead,

they denote sets of elements, namely, they have what Stavrou and Terzi 2008 call set interpretation.

(39)

a.

b.

Agorase tesseris ekatondadhes vivlia.

bought-3s four hundred-adhes books

‘She bought four sets/boxes/etc. of a hundred books.’

Efere

tris eksadhes bires.

brought-3s three six-adhes beers

‘She brought three (packs of) six beers.’

In (39a)=(6a) ‘four hundred books’ refers to books packed in four sets (e.g. boxes) that contain a

hundred books each. Likewise, in (6b) the English ‘pack(s) of beers’ comes out as ‘six+-adhes beers’ in

Greek. Stavrou and Terzi (op.cit.) consider such numerical nouns in –adha as semi-lexical (van

Riemsdijk 1998), comparable to the classifier phrases of Chinese (Chierchia 1998; Cheng and Sybesma

1999; Loebel 2001; Stavrou 2003).

(40)

DP

4

Though Lyons 1999 rejects this view arguing for a category that is higher in the DP

.

11

wo

D

i

(the)

NumP

ei

tris

three

Num’

ei

Num

[+PL]

NumclP

ei

Numcl’

ei

Numcl

ekatondadhes

NP

vivlia

hundred-adhes

books

eksadhes

bires

six-adhes

beers

[NumclP=Numerical Phrase]

The Numerical Phrase (NumclP) in (38) is headed by a numerical noun formed by a lower cardinal to

which –adha is suffixed and introduces a Pseudopartitive (PsP) construction (van Riemsdijk 1998, and

Stavrou 2003 for Greek). The PsP is one nominal phrase with a single referent, despite the inclusion of

two nouns in it. Such nouns actually always select some lexical noun (here bires), hence, they are

relational.

Like all other nouns of this type, ekatondadhes ‘sets of a hundred’ or eksadhes ‘sets of six’, in (6),

select as their complement a lexical noun, i.e., vivlia ‘books’ and bires ‘beers’ respectively.

A major characteristic of (40) is that the two participating nouns share the same case, which is the case

assigned to the topmost D from an external assigner.

5.2

Numerical Nouns with cardinal interpretation.

(41)

I vivliothiki tu panepistimiu

exi tris xiljadhes vivlia.

the library the-gen university-gen has three thousand books

‘The university library has three thousand books.’

Question:

What is the structure of complex cardinals with numerical nouns and how do they differ

from those complex numerals with set interpretation (given their identical appearance)?

There are in principle two alternatives:

a) the complex cardinal in (41) is assigned the structure of the pseudopartitive in (40).

b) the structure of the complex cardinal is as in (43)

The first alternative comes out in the two variants below:

(a) tris xiljadhes ‘three thousand’ is analyzed just as tris ekatondadhes ‘three hundred’ in (40), given

that these complex numerical expressions look the same morphologically, in the sense that they are

formed out of a cardinal to which the suffix –adha is added.

(42a)

12

DP

wo

D

ta

(the)

NumP

ei

tris

Num’

ei

Num

three

NumclP

ei

[+PL]

Numcl’

ei

Numcl

NP

xiljadhes

vivlia

thousand-adhes

books

(b) tris xiljadhes participates in a pseudopartitive structure such as in (40), which, however, now is in

the specifier position of NumP, (40b); it does not form part of the main skeleton of the nominal

projection 5

(42b)

DP

ei

D

(ta)

NumP

wo

DP/NumP

(the)

ei

tris

three

Num’

ei

Num‘

ei

Num

NP

vivlia

[+PL]

Num

NumclP

[+PL]

ei

books

Numcl’

xiljadhes

thousand-adhes

The difference between (42a) and (42b) is that in (42b) the pseudopartitive is part of the specifier of

(the main) NumP . Hence, in (42b) it is the noun vivlia that is the head of the entire cardinal expression,

by contrast to (42a), where the head is the numerical noun.

According to the second alternative, the complex cardinal of (41) is also in Spec, NumP, but its second

word is not dominated by NumclP. As previously, the complex cardinal in the specifier of NumP is a

DP, and the definite determiner agrees with the lexical noun in gender.

(43)

DP

ei

5

Ionin and Matushansky 2006, in their example (22b), consider a similar solution for complex cardinals of

languages like English. A difference between their (22b) and our (45b) above, which is consistent with their aim to account

for recursivity, is that their counterpart of our NumclP is null and both three and thousand are modifiers of it. We suspect

that their view is in a position to also explain why English three thousands is ungrammatical, assuming that thousand is a

syntactic modifier as well, viz., an adjective, and adjectives do not inflect for number in English.

13

ta

(the)

NumP

ei

DP/NumP

Num’

ei

ei

tris

Num’

Num

three

ei [+PL]

vivlia

Num

xiljadhes

[+PL]

thousand-adhes

Question:

NP

books

How can we choose among (42a, b) and (43)?

Our decision will be based on:

(i) the agreement in phi-features between the various elements of the cardinal construction,

(ii) the ‘compound’ nature of complex cardinals, and

(iii) the interpretation with which each one of the three structures is associated:

We take up each one of the above factors:

5.3 Agreement patterns

Below is a mainstream complex cardinal involving xiljadhes.

(10)

a.

ta

tris

xiljadhes

vivlia

the.neut.pl.acc/nom three.fem.pl.acc/nom thousand.fem.pl.acc/nom

books.neut.pl.acc/nom

b.

??i

tris

xiljadhes

vivlia

the.fem/masc.pl.nom three.fem.pl.acc/nom thousand.fem.pl.acc/nom

books.neut.pl.acc/nom

We noted in section 3.1 the agreement paradox according to which complex cardinals do not agree in

gender with the lexical noun. We attributed this mismatch to the fact that the second part of the

complex is a noun, and, as such, it comes with its own gender features.

How come tris xiljadhes does not violate gender agreement?

The complex cardinal is opaque for the rule of agreement that holds for the NumP as a whole.

Alternatively, xiljadhes checks its gender feature against that of tris, which is the functional element in

this complex and the checked gender feature is erased.

The agreement pattern of the complex cardinal with the article excludes (42a) as a candidate. If

the structure of complex cardinals was as in (42a), the article would have to agree with its complement

noun, i.e., the numerical noun, as it does in complex numerals with set interpretation:

(44)

a.

i

tris

ekatondadhes

vivlia

the.fem.pl.acc/nom three.fem.pl.acc/nom hundred.fem.pl.acc/nom

books.neut.pl.acc/nom

b.

*?ta

tris

ekatondadhes

vivlia

the.neut/masc.pl.nom three.fem.pl.acc/nom hundred.fem.pl.acc/nom

books.neut.pl.acc/nom

14

We turn next to point (ii), namely, to the issue of compound formation of the simplex cardinal and the

noun xiljadhes that follows it and constitute the complex cardinal together.

5.4 Complex cardinals as compounds?

The structure in (43) provides us with an insight to some further facts concerning complex cardinals

like tris xiljadhes. Such cardinals can be taken to form a syntactic (two-word) compound and the two

parts involved are found in just the right configuration for compounding to be effected. It has been

independently argued that strings of the A+N or N+N type can form together a single N despite the

appearance of internal inflection in Greek (Anastasiadi-Simeonidi 1986, Ralli 1992, Ralli and Stavrou

1997). Such two-word compound Ns may be formed either in the syntax or in the lexicon, see (45a)

for the former and (45b) for the latter type. An important difference between (45a) and (45b) is the

compositional character of (45a) and the ‘opaque’, or idiosyncratic, character of lexical compounds as

in (45b).

(45)

.

a.

b.

sxoliko leoforio

school adj neut.sg bus.neut.sg

laiki agora

popular market

‘school bus’

‘open market’/‘farmers’ market’

A crucial factor for the formation of syntactic compounds, as in (45a), is that nothing separates the two

elements of the compound, a situation also met by the complex cardinals involving xiljadhes

‘thousands’. Moreover, the meaning of complex cardinals involving xiljadhes is compositional.

In the structure in (43) nothing ever intervenes between tris and xiljadhes and the two elements are

found within the same maximal projection – NumP.

By contrast, in (42a) and (42b) each of the two parts that constitute the complex cardinal is within a

different projection, namely, NumP and NumclP.

The compound status of complex cardinals, tris xiljadhes, can be the base for the formation of an

ordinal adjective:

(46)

trisxiliostos, tesseraxiliostos

3000th, 4000th

The complex ordinal in (46) is exactly parallel to tritos ‘third’, defteros ‘second’, etc., which are

derived from simplex cardinals. If they did not count as a single word they could not constitute the

basis for the derivation of an ordinal adjective.

Notice that ordinary A+N syntactic compounds give rise to derived (denominal) adjectives as well:

(47)

a. dimosios ipalilos < dimosioipalilikos (adj)

state (public) employee

b. dimosios nomos < dimosionomikos (adj)

public law

‘pertaining to a state employee’

c. ekso pragmata < eksopragmatikos (adj)

outside things

‘non-real’

‘pertaining to a public law’

15

The compound status of complex cardinals has the consequence that their use as predicative elements

comes out for ‘free’, i.e., complex cardinals are used in predicative position just as simplex cardinals

are.

(48)

Cf.

a. Ta vivlia tis viliothikis

ine tris xiljadhes.

the books the.gen library.gen are three thousands

b. Ta vivlia tis vivliothikis tu

ine enea.

the books the.gen library.gen his are nine

c. O Janis ine dimosios ipalilos

the Jani is state (public) employee

Complex cardinal

Simplex cardinal

A+N compound

Ionin and Matushansky (2006) reject the idea of complex cardinals as predicate modifiers precisely on

the basis of the wrong semantics that would arise if each one of the two parts of the complex cardinal

was used predicatively. Under the assumption that the two parts form a compound in Greek, no such

contradiction arises, since, three thousand, just as three, behave in the same manner as predicates.

Conclusion: (43) is preferred over (42a-b) on compound formation grounds.

Note that there is no evidence that a numerical noun with set interpretation can ever form a compound

with its preceding cardinal, as there is no derived word out of such a (hypothetical) compound – nor

could we detect any other process that would use the string cardinal+numerical noun with set

interpretation as a base.

5.5 The interpretation of (42) and (43)

The third reason why we do not consider either version of (42) as the structure for complex cardinals

involving xiljadhes, is its interpretation. The interpretation of tris xiljadhes is the interpretation of any

other cardinal, and is different from the set interpretation that ekatondadhes and other such numerical

nouns have. Therefore, xiljadhes cannot possibly be dominated by NumclP, which we take to be

associated with set/group nouns. This last fact is captured by (43), but not by (42).

Alternatively put, we believe that xiljadhes, in contrast to ekatondadhe for instance, is not a

semi-lexical noun, despite the presence of the nominalizing suffix -adhes, but just a noun, albeit a

cardinal one. In other words, it is not of the numerical kind that act as classifiers, this is why it does

not have a set reading. Xiljadhes falls under the category ‘M’ of Hurford 1987 (like English hundred, ty, thousand). Independent support we get from Hurford (1987: 239), where it is explicitly stated that

“…the fact that in multiplicative constructions, the Noun has to be a ‘Numeral Noun’, i.e., one formed

of a numeral.” But if xiljades is not a relational noun, it comes as no surprise that it does not take a

complement and does not get a set interpretation either. It is for this reason that we do not take

xiljadhes to be inserted in the position of ekatondadhes ‘hundreds’.

Thus, once again we conclude, (43) is the structure for Greek complex cardinals involving

xiljadhes. Xiljadhes is inserted in the complement position of (the embedded) NumP, getting its

cardinal interpretation next to the simplex cardinal that resides in the specifier of the same projection.

Since the complex cardinal it forms with the preceding lower cardinal is not in the c-commanding

domain of the determiner, it does not agree with the determiner in gender. Instead the determiner

agrees with the lexical noun.

5.6 A note on ekatomirio

There is one more complex cardinal of the multiplicative type, ekatomirio ‘a million’, (4b).

16

(49)

I vivliothiki tu panepistimiu exi tessera ekatomiria vivlia.

the library the university-gen has four million books

‘The university library has four million books.’

ekatomirio differs from other numerical expressions in a number of ways.

a) it differs trivially from monomorphemic cardinals such as ‘one’, ‘two’, ‘three’, etc. in that it is not

monomorphemic.

b) it differs from bi-morphemic cardinals in that it is a compound noun, formed out of two cardinal

roots: ekato ‘hundred’ and –mirio ‘ten thousand’ in ancient Greek. In other words, no grammatical

suffix is implicated in the formation of ekatomirio, unlike the bi-morphemic xiljadhes ‘thousand(s)’

that is employed in the other type of complex cardinals.

c) it differs from cardinals such as xilja ‘thousand’, in that it has to be preceded by the article.6

At the same time, ekatomirio is similar to all the above elements, in that it is a cardinal, and not a

numerical noun with set interpretation.

It is surprising therefore, that unlike the complex cardinal with xiljadhes ‘thousand(s)’, but like

the complex numerals with set interpretation, (44), the definite article that precedes ekatomirio must

agree in gender with it, rather than with the lexical noun.

(50)

a

b.

ta

tria

ekatomiria

tomi

the.neut.pl.nom three.neut.pl.nom millions.neut.pl.nom

volumes.masc.pl.nom

??i

tria

ekatomiria

tomi

the.masc/fem.pl.nom three.neut.pl.nom millions.neut.pl.nom

volumes.masc.pl.nom

Thus, although ekatomirio has a cardinal interpretation, it is unlike other cardinals (simplex or

complex) in that when it is preceded by the definite article, the article agrees with it rather than with the

lexical noun – resembling in this sense complex numerals with set interpretation.

One way of making sense of the above gender agreement facts is to say that ekatomirio

‘million’ is a semi-lexical noun, just like ekatondadhes ‘hundreds’, hence, its structure is as in (40).

This explains gender agreement.

However, this implies that the numeral in (49) has a set reading, something that is not easily

perceived. It may be that the reading of (49) is indeed that of a set counting noun, but we do not

perceive as such because of purely pragmatic reasons, i.e., because it is difficult to imagine sets

consisting of a million items each. Tricky as it may seem such an explanation at first glance, we would

be willing to accept it if it was not for the two disturbing pieces of data below.

First, if gender agreement in (50a) is so because ekatomirio is in fact a numerical noun with set

interpretation, it is difficult to see why gender agreement with the lexical noun is not as bad as it is with

the other set denoting numerical expressions, see (44b).

Moreover, if indeed the structure of (49) is as in (40)=(42a), one would expect ordinals with

ekatomirio not to be possible. As argued in section 5.4, ordinals are possible with xiljadhes, but not

with ekatodadhes because the former are (syntactic) compounds. This is not the case with complex

cardinals involving ekatomirio, however, which nevertheless can form acceptable ordinals:

6

Apparently, xilja is itself an adjective, not a noun, as can be verified by the simple fact that it alone modifies the noun:

xilja tragudja, ‘a thousand songs’, just like any other simplex cardinal (or adjective for that matter). Moreover it displays

the kind of agreement illustrated in (9a-b). So in order for eksi ‘six’, for instance, to be able to modify xilja, xilja has to be

noun or, more noun-like. This seems to be the effect of the suffix –adha that we have discussed, i.e., to convert xilja into a

noun, which then becomes an appropriate modifiee of ‘six’ (‘two’, ‘three’, etc.), resulting in eksi xiljades ‘six thousand’, etc.

17

(51)

trisekatomiriostos, teseraketomiriostos, etc.

3.000.000th , 4.000.000th

The structure of complex cardinals involving ekatomirio ‘million’ requires further investigation. Once

we have something more concrete to say, our claims concerning the syntactic structure of the other

complex cardinals will be even more strengthened.

6.

Summary - Conclusions

▪ Greek cardinals are like adjectives, in the sense that they agree in phi-features with the lexical noun.

Hence, they can be considered as syntactic modifiers. However, they can introduce a bare nominal,

unlike adjectives.

▪ We claim that this is so because an empty D is present in their structure, on which the cardinal, from

the specifier of NumP that we consider it to be located, imparts existential force.

▪ Being at a specifier position, cardinals agree with the associated lexical nouns in phi-features.

▪ Morphologically identical complex numerals demonstrate a different syntax, on par with the above

claims regarding the syntactic and semantic properties of cardinals.

REFERENCES

Alexiadou, A., Haegeman, L. and M. Stavrou. 2007 (Alexiadou et al.). NP from a generative

perspective. Mouton de Gruyter.

Anastasiadi-Symeonidi, A. 1986. Neology in modern Greek Koine (in Greek). Thessaloniki. Aristotle

University.

Barbiers, S. 2007. Indefinite numerals ONE and MANY and the case of ordinal Suppletion. Lingua 117:

859-880.

Barwise, J. and Cooper, R. 1981. Generalized Quantifiers and Natural Language. Linguistics and

Philosophy 4, 51-93.

Bouchard, D. 2002. Adjectives, Number and Interfaces. Why Languages vary. Amsterdam, Boston:

Elsevier.

Cardinaletti, A. and Giusti, G. 2005. The syntax of quantified phrases and quantitative clitics. In H. van

Riemsdijk & M. Everaert (eds.), The Blackwell Companion to Syntax. Vol. 5. Oxford:

Blackwell, 23-93.

Cheng, L.-S. and Sybesma, R. 1999. Bare and Not-So-Bare Nouns and the Structure of NP. Linguistic

Inquiry 30: 509-542.

Chila-Markopoulou, D. 2000. The indefinite article in Greek. A diachronic approach. Glossologia 1112, 11-130. Athens, Leader Books.

Chierchia, G. 1998. Plurality of Mass Nouns and the notion of ‘Semantic Parameter. In S. Rothstein

(ed.), Events and Grammar. Kluwer, 53-103.

Cinque, G. 1994. On the Evidence for Partial N-movement in the Romance DP. In G. Cinque, J.

Koster, J.-Y. Pollock, L. Rizzi & R. Zanuttini (eds.), Paths to Universal Grammar. Studies in

Honor of R. Kayne. Georgetow University Press, 85-110.

Cinque, G. 1999. Adverbs and Functional Heads. A Crosslinguistic Perspective. New York/Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

Cornilescu, A. 1993. Notes on the Structure of the Romanian DP and the Assignment of the Genitive

Case. In University of Venice Working Papers in Linguistics. Vol. 3, n.2. Pp. 107-133.

18

Corver, N. and Zwarts, J. 2006. Prepositional Numerals. Lingua 116: 811-835.

Danon, G. 2009. Grammatical number in numeral-noun constructions. Handout Bar-Ilan University.

Den Dikken, M. 2006. Linkers. MIT Press

Diesing, M. 1992. Indefinites. MIT Press.

Embick, D. 2007. Blocking Effects and Analytic/Synthetic Alternations. Natural Language and

Linguistic Theory 25:1.

Etxeberria, U. and A. Giannakidou. 2010. D-heads, domain restriction, and variation: from Greek and

Basque to St'at'imcets Salish. Ms. IKER-CNRS & University of Chicago.

Giannakidou, A. 2004. Domain restriction and the arguments of quantificational determiners. Talk at

SALT 14. Cornell University, Ithaca, NY.

Giannakidou, A. 2011. Quantification, (In)definiteness and specificity: syntax and semantics. Talk at

the 32nd Annual Meeting of the Dept. of Linguistics, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki.

Giannakidou, A. and Stavrou, M. 1999. Nominalization and Ellipsis in the Greek DP. Linguistic

Review 16: 295-331.

Giusti, G. 1991. The categorial status of quantified nominals. Linguistische. Berichte 136: 438-452.

Giusti, G. 1997. The categorial status of determiners. In L. Haegeman (ed.), The New Comparative

Syntax. Longman.

Grimshaw, J. 1991. Extended Projection. Ms. University of Rutgers.

Heycock, C. and Zamparelli, R. 2005. Friends and colleagues: Plurality, coordination and the structure

of DP. Natural Language Semantics 13:201-270.

Hurford, J. 1987. Language and Number. Blackwell.

Jackendoff, R. 1977. X’-Syntax. A theory of Phrase Structure. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. Linguistic

Monograph Series.

Ionin, T. and O. Matushansky. 2006. The Composition of Complex Cardinals. Journal of Semantics

23: 315-360.

Kratzer, A. 1998. Scope or pseudoscope? Are there wide scope indefinites? In S. Rothstein (ed), Events

and Grammar. Kluwer. Dordrecht, 163–196.

Kayne, R. 2006. A Note on the Syntax of Numerical Bases. In Y. Suzuki (ed.), In Search of the

Essence of Language Science: Festschrift for Professor Heizo Nakajima on the Occasion of his

Sixtieth Birthday. Tokyo: Hituzi Syobo, 21-41.

Landman, F. 2003. Predicate-argument mismatches and the adjectival theory of indefinites. In M.

Cohene and Y. D’hulst (eds.), The Syntax and Semantics of noun phrases. Linguistics Today

55. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 211-237. Landman, F. 2004. Indefinites and the types of

sets. Blackwell.

Loebel, L. 1990. Q as a functional category. In Ch. Bhatt, E. Loebel & C. Scmidt (eds.), Syntactic

Phrase Structure Phenomena in Noun Phrases and Sentences. Amsterdam: John Benjamins,

135-160.

Loebel, L. 1993. On the Parametrization of Lexical Properties. In G. Fanselow (ed.), The

Parametrization of Universal Grammar. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 183-199.

Loebel, L. 2001. Classifiers and semi-lexicality: Functional and semantic selection. In N. Corver &

H.Van Riemsdijk (eds.), Semi-lexical Categories. Berlin, NewYork: Mouton de Gruyter, 223272.

Longobardi, G. 1994. Reference and Proper Names: a Theory of N-Movement in Syntax and LF.

Linguistic Inquiry 25: 609-665.

Lyons, C. 1999. Definiteness. Cambridge University Press.

Marinis, Th. 2005. Subject-object asymmetry in the acquisition of the definite article in Greek. In

Stavrou, M. and A. Terzi (eds), Advances in Greek Syntax. Studies in honor of Dimitra

Theophanopoulou-Kontou. 153-178.

Marmaridou, S. 1984. The study of reference, attribution and genericiness in the context of English and

19

their grammaticalisation in M. Greek noun phrases. Ph.D Diss. University of Cambridge.

Milsark, G. 1977. Toward an Explanation of certain Peculiarities in the Existential Construction in

English. Linguistic Analysis 3: 1-30.

Montague, R. 1973. The proper treatment of quantification in ordinary English. In Approaches to

Natural Language. J. Hintikka, J. Moravcsik and P. Suppes (eds.), 221-242. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Reprinted in Formal Philosphy, R. Thomason (ed.), 247-270. New Haven, Yale University

Press, 1974.

Partee, B. 1987. Noun Phrase interpretation and type shifting principles. In Studies in Discourse

Representation Theory and the Theory of Generalized Quantifiers. J. Groenendijk, D. de Jongh

and M. Stokhof (eds.), 115-43. Dordrecht, Foris.

Riemsdijk, H. van. 1998. Categorial Feature Magnetism: The endocentricity and distribution of

projections. Journal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics 2: 1-48.

Ralli, A. 1992. Compounds in Modern Greek. Rivista di Linguistica 4:143-174.

Ralli, A. and Stavrou, M. 1997. Morphology-syntax interface: A-N compounds vs. A-N constructs in

Modern Greek. Yearbook of Morphology 1997: 243-264.

Ritter, E. 1991. Two Functional Categories in Noun Phrases: Evidence from Modern Hebrew. In S.

Rothstein (ed.), Syntax and Semantics 26. San Diego: Academic Press, 37-62.

Roussou, A. and Tsimpli, I.M. 1993. On the interaction of case and definiteness in Modern Greek. In

Themes in Greek Linguistics, I. Philippaki-Warburton, K. Nikolaides and M. Sifianou (eds).

Amsterdam: John Benjamins. 69-76.

Rutkowski, P. 2008. Case study: The Nominal Syntax of Polish. Handout. Academy of Lithuania,

Salos.

Selkirk, L. 1977. Some remarks on noun phrase structure. In P. W. Culicover, T. Wasow & A. Akmajian

(eds.), Formal Syntax. London: Academic Press, 285-316.

Sioupi, A. 2001. The distribution of object bare singulars. In Proceedings of the 4th International

Conference on Greek Linguistics. Nicosia, Cyprus. G. Agouraki et al (eds). Thessaloniki:

University Studio Press. 292-299.

Shlonsky, U. 2004. The form of Semitic Noun Phrases. Lingua 114 (12):1465-1522.

Stavrou, M. 1983. Aspects of the structure of the Noun Phrase in Modern Greek. Unpublished Ph.D

Thesis, University of London.

Stavrou, M. 2003. Semi-lexical nouns, classifiers and the interpretation(s) of the pseudopartitive

construction. In From NP to DP, M. Coene & Y. D’Hulst (eds.), From NP to DP. Amsterdam:

John Benjamins, 329-354..

Stavrou, M. and Terzi, A. 2008. Types of numerical nouns. In C.B. Chang & H.J. Haynie (eds.)

Proceedings of the 26th WCCFL. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, 429-437.

Van Riemsdijk, H. 1998. Categorial Feature Magnetism. The endocentricity and distribution of

projections. Journal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics 2:1-48.

Wiese, H. 2003. Numbers, Language and the Human Mind. CUP.

Zamparelli, R. 2000. Layers in the Determiner Phrase. New York: Garland. .

20