CeriButler1

advertisement

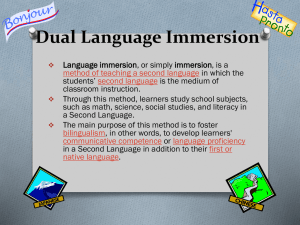

Ceri Butler Immersion in Queensland In 1992 the language department at Park Ridge SHS had the opportunity to propose the establishment of the first Indonesian Immersion program outside Indonesia.. This program has now been operating for nearly ten years, and we decided that now was a good time to undergo a formal review; reflecting on the outcomes and evaluating the effectiveness of instruction. The results of this review will be used to ensure the continued success and improvement of the program. I’ll start the paper with a brief background of the setting up of the program, and then outline some of the key issues for programs of this kind. A language-immersion program is one where the subject matter is taught in a second language. So the language is the medium of instruction rather than the object of instruction. At Park Ridge SHS, it was originally planned to establish a program where all the curriculum activities would be conducted in the Indonesian language; a 'total' immersion program. In initial discussion with parents, though, concerns were voiced that the course be of a high overall academic standard. Language acquisition was secondary to them. Because of this concern, and because it was still experimental, it was decided to offer a partial immersion program. We thought very carefully, then, about the subject or content areas that would be most appropriate for immersion. Bahasa Indonesia was an obvious choice. Science and mathematics were both included. These are subject areas with lots of concrete or tangible content, so they are easily presented in the language of immersion. SOSE was added, as it is another compulsory of the component of the curriculum. So students were assured of having broad curriculum experience from which to draw for senior subject selections in years 11 and 12. This also satisfied the need for academic rigour expressed by the parent body. Staffing was another factor in the decision to offer only partial immersion. It has proved to be very difficult to find qualified teachers who have expertise in a given subject as well as in the language area. In fact, staffing of even a partial immersion program, where up to 50% of the course is covered in Bahasa Indonesia, is always a problem. A key part of the problem is that many people who have studied Indonesian at tertiary level have combined it with arts subjects. So staffing for maths and science is problematical. In addition, very few native Indonesians responded to the initial advertisements and none had the required maths or science background. Finding suitably qualified staff has been an ongoing issue, not only in the Indonesian immersion program but in all the immersion programs offered by Education Queensland. The original staff employed in 1993 consisted of a native Indonesian who was trained as a SOSE teacher in Australia and a non-native but highly proficient math teacher with extensive in-country experience and some science background at tertiary level. The program has been fortunate to maintain the original Indonesian teacher but had to replace the science/maths teacher in the third year of the program. Two part-time Malay teachers took up the challenge and were joined in 2001 by an additional Australian teacher with in-country experience. One of the Malay speakers had completed a tertiary degree in the Indonesian language. The difference in the Malay and Indonesian languages meant that the teachers needed to develop close working arrangements. Language-checking by the native speaker became paramount to 1 Ceri Butler Immersion in Queensland maintain the language integrity of the program. This impacted on the time allocation needed for the teachers’ development of course materials. A further constraint on teacher time was the need to develop all course materials. There were no suitable materials available from Indonesia because of the difference in curriculum content in Indonesia and Queensland. To support the teachers in this endeavor a number of administrative procedures were needed. Time to develop the materials had to be timetabled and factored into teachers’ allocations of duties. A teacher aide was also employed to compile the curriculum documents and give much needed support in their production. Purchasing of supporting Indonesian curriculum materials was needed especially in the Science curriculum areas to ensure the correct use of terms. Not only was this purchasing expensive but also problematical as no Indonesian book suppliers in Australia could cater for these needs. This meant that resources needed to be purchased in Indonesia. The funding of this kind of program is outside standard budgetary allocations. Special funding was sought and delivered by Education Queensland. Two Full time teacher allocations were made to the school as extra to the school’s allocation. An initial funding of $12 000 was given in 1993. This was increased to $15 000 in1994 and further increased to $17 000 in 1995. Changing political environments saw the continual decrease in funding until in 1998 funding ceased all together. The outcomes of the program were sufficiently established and obvious by this time for the school administration to take up the short fall and continue to fund the program from internal budget allocations. Unfortunately, this has resulted in a decrease in the time allocation of the teacher aide and purchasing of materials. The implementation of 3 new syllabi and a fourth soon to come on line will place further pressure on existing resources and time as teachers struggle to develop appropriate materials to suit the new syllabi. In 1993 the first intake of 33 students occurred with students studying the four subjects of Indonesian, Science, SOSE and Mathematics. The lessons of that first year saw the additional subject of typing included in 1994 to help develop procedural language for the students prior to the introduction of Science in term 2. Over the next 4 years woodwork, graphics and cooking in term 1 became Immersion subjects using second subject area skills of language teachers on staff. With mainstream Indonesian language teachers of very high proficiency on staff, it became possible to develop students’ mastery of procedural and general language proficiency through Indonesian lessons in term 1, in preparation for managing the demands of science and SOSE which are introduced in term 2 of year 8. During the early stages of development there was considerable opposition from the teachers outside language curriculum areas. In the second year of the program the English department in the school offered their first term time tabling slot of English to the Indonesian immersion teacher to further enhance language skills. The support of the English department was the catalyst for school-wide acceptance. This meant that an overall acceptance of and support for the program from teachers in other content areas began to develop. The proficiency and academic outcomes of the program are now well documented. Since 1995 when the first year Immersion students reached Year 10, an immersion student has been 2 Ceri Butler Immersion in Queensland Junior dux five years out of six and Senior dux three years out of five. In the National Australia Bank Language Certificate 60% to 75% of Immersion students have been in the top 10% of Australian and New Zealand students. The proportion of ex-immersion students enrolling in further education far exceeds the school average in any given year. The proficiency outcomes can be seen in the students exit level of achievement in year 10 and year 11 in comparison to non-immersion students. In 1999, over 80% of year 10 immersion students scored a Very High Achievement in comparison to 30% non-immersion. More than 60% of year 12 ex-immersion students of the same year scored VHA's in comparison to 20% of non-immersion students. Those students who have continued their studies on to tertiary level are accepted into second year or third year university Indonesian language studies based on the very high proficiency levels gained. As the program was being developed, parents voiced concerns about the levels of support that students and parents could expect. Parents, in general, felt helpless and inadequate about supporting their own children in this kind of learning. Support networks were an integral component of the success of the program, and continue to be important as the program progresses. These networks involve student self support as well as the more formalised 'buddy system' where students receive the phone number of 3 other students from within the program across year levels as well as the home phone numbers of their teachers. This system has developed a supportive learning environment across the program as well as developing self-directed learners with less need for teacher help. Students can also access extra tutorials during school time and after school. The parents’ natural desire to help and support their students is made all the more difficult in an immersion context because of their lack of linguistic knowledge. Initial 'How-to-helpyour-Immersion-Student' meetings are held. At these meetings parents are taught how to use a bilingual dictionary, take part in an immersion lesson and issues of parental support are discussed. To further alleviate parents’ feelings of helplessness, parent coffee evenings were inaugurated in 1998. These are held every term and in term 4 include the parents of the new intake for the coming year. These evenings have led to a casual parent support network developing outside the school. Parents now have the support of each other as well as of the teachers and administrators. As many families enroll second and third children, a pool of 'expert' parents has developed. One of the ongoing issues for the program is student enrolment. In 1995 the intake of students was very low. Community perception of Indonesia impacted on the numbers of students applying for entrance to the program. The process for information to the community was extended. Information sessions are now held in all feeder schools with students and teachers, and are followed with parent information evenings. At these meetings, the language outcomes and subsequent job opportunities are explained. Issues about academic development and standing , work ethics, cultural understanding and social outcomes are now emphasized as well as the language proficiency outcomes. Over time, the parents have come to recognise these other benefits to their students. Inter-cultural understanding and tolerance, strong work ethics, independent and consistent learning habits and the development of excellent study skills that transfer over to other subject areas have been identified by all stakeholders. 3 Ceri Butler Immersion in Queensland This outline has demonstrated that the main challenge for the program is not related to student achievement. It has been shown that immersion student proficiency outcomes far surpass those of non-immersion language students. The main challenges are in the areas of pedagogy and inter-cultural understanding. There is an ongoing need to support the development of language teaching skills in immersion teachers. The pedagogical challenge for the content area teachers is to use language teaching methodology, that is, to apply a language-in-use or communicative approach where the focus is on the process of using language rather than on language as the product. As the requirement for being an immersion teacher includes language proficiency and content area knowledge, it is easy to overlook qualifications in pedagogy. Only one of the native teachers has training in language methodology. It is necessary to continually encourage the development of language teaching skills that enhance language-learning as well as content area outcomes. The immersion teacher needs to employ many strategies to help the students understand the content area curriculum. The comprehensible input skills are paramount to building language proficiency. From observations and discussions it is evident that this is more of a challenge for the native teachers in the program. When faced with lack of understanding or misunderstanding from the students, they are more likely to revert to English than non–native Indonesian teachers who apply a range of strategies to achieve student comprehension. There are clear professional development implications in this for the program. Teachers need to train and network together so that there is a pooling and transferring of respective skills. Native-speaker teachers can contribute language expertise, while others can contribute pedagogic skills and strategies, for everyone’s mutual benefit. In this way, teachers will work together as a team on a task-based curriculum framework, to ensure that the immersion program of the new millennium is more effective than ever. Achieving genuine intercultural understanding as part of the program outcomes emerges as another key challenge. One of the expected outcomes of the program is an increase in intercultural understanding. The pursuit of this has led to some interesting moments in the immersion program. To have teachers from one culture interacting with students, parents and administrators from another culture has, at times, lead to misunderstandings and tension. Through the parent support networks, both formal and informal discussions have taken place in the effort to give cultural background knowledge to help develop more of an understanding of how parents and students can talk with and interact with the native immersion teachers. For the teachers, formal inservice sessions about the need to individualise learning and apply multiple intelligence theory have been offered, as well as informal discussions on the students’ and parents’ perspectives. It is only through explicitly attending to any cultural misunderstandings that it has been possible for some parties to bridge the gap between cultures. An interesting observation is that this bridging seems to be more easily accomplished on the part of the students and parents, rather than the native speaker teachers, perhaps because of some subliminal notion of ‘expert’ in their understanding of the studentteacher relationship. Clearly, inter-cultural understanding needs to remain an integral component of the immersion program, with all participants encouraged to find that ‘middle’ 4 Ceri Butler Immersion in Queensland place where comfortable and appropriate interaction with people from another culture can occur. Any repercussions for teacher professional development and for explicit mediation of culture in immersion lessons need to be incorporated into the management of the immersion program. The immersion program described here is a source of great pride for those who developed it and have seen it grow from success to success. Yet no-one is complacent about it. We are all aware that there is always more to learn, and many ways to improve. Those involved in the program are committed to its ongoing development and renewal so that the immersion program remains a vital one, one that continues to attract committed students and one that continues to develop high levels of outcomes. 5