Women`s Contributions to the Economy of Medieval Towns ()

advertisement

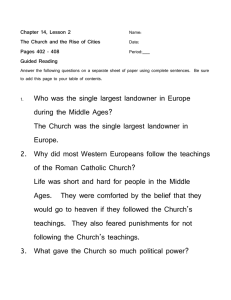

WOMEN'S CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE ECONOMY OF MEDIEVAL TOWNS Women were viable members of the economy of medieval towns in the Middle Ages. They were not able to participate in the formal political process of the towns, but unlike monarchies which were dynastic, political service in towns was by election. This republican form of governing, whether through consuls and communes in Italy and parts of France or through mayors and common councils in England, meant that men had the exclusive right to be citizens and serve in the governmental structure. While infrequently mentioned in the surviving sources, enough information is available to relate their economic contributions, and the wide-variety of employment opportunities they had. Women made their testaments, witnessed charters and deeds to property, and were subject to the legal system, all of which produced documentation. A woman's right to make a will, if she was married, had not completely become law by the late medieval period, but the church had long advocated this right. Widows and spinsters could make their testaments without the approval of a male. Far fewer female than male criminals appear in medieval court records. Some studies show the ratio was 1:9. Women were punished for crimes just like men, but their punishments were often times different. Women were usually punished by some kind of public physical shame. Common convictions for women had to do with them being quarrelsome and overtalkative women. France made the women take off all their clothes except their shift, and then carry around their neck a hefty stone circling the church on Sunday in full view of their fellow parishioners. In England the favored punishment was the ducking stool and the thewe, a pillory just for women. Women were also beaten if they were guilty of being accomplices in minor crimes. In the high middle ages, being burned at the stake or buried alive were the only forms of capital punishment for women, apparently out of fear the corpse if hung might be profaned; that is sexually asssaulted. Burning was usually reserved for the most serious offenses: treason, sorcery, and infanticide. Later on hanging, especially in England, will be added. Torture was an integral part of the justice system, and here again women were excepted from certain forms of torture. They could not be broken on the wheel, and if the woman was pregnant then she was exempted from all forms of torture and even execution. 2 Our most fulsome knowledge on women in towns comes from their economic contributions. Girls and women were generally expected to work in addition to their usual occupation of keeping the house. As large-scale manufacturing did not exist in the middle ages, each home was a cottage industry unto itself. Parents served as the mentors of their daughters, teaching them their trades, including how to run a household, because most all women would marry. Only about seven to ten percent did not wed. In towns, the workplace or shop was attached to the living quarters. Only in a few specialized skills such as silk manufacturing did women go outside the home or family-run shop to serve an apprenticeship, and only if the parents could afford the fees. Once the young maidens married they would continue to practice the occupations they had learned at home, while taking care of their family. Many times they learned new skills during their lifetime or were taught their husband's trade enough to assist him in the family-run shop. In contrast men pursued a more or less steady course whether they were peasants, urban workers or nobles. Men acquired the necessary skills for their occupation and continued to work until old age or death. Marriage and having a family might make their work more or less profitable, but it did not change what they did. Women's occupations were influenced by changes in their life cycle. Unmarried women generally held lower-status jobs with the majority of them domestic servants, and then retailers: sellers of food, new and used household items and clothing. Some towns placed restrictions on certain jobs based on a woman's marital status. For instance, generally single women did not brew ale in rural England. Women who operated their own businesses without a male were called femme soles. If a femme sole became involved in a legal dispute her husband was not held responsible. Only when the married couple was in business together was the husband held libel. In widowhood a woman had lots more options. She could determine to remarry or not, and whether or not to continue with her husband's business. Women could therefore change their work frequently over the course of their lifetime. The magistrates of England recognized this when the Statue of Laborers was reissued in 1363. All men were required to choose a trade and confine themselves to it exclusively, but women were not limited to one occupation. They could be "dabblers". A woman might concentrate on thread production if that was paying well, but switch to brewing or retailing if the market was more robust in those areas. As women's training was primarily for the domestic 3 sphere, they were unlikely to develop skills that would permit them to enter high-status positions. Men were reluctant to admit women into their craft and its mysteries. A wife and daughter might be taught part of the mystery, but not the whole process. Men believed that if women entered their craft, they would take over because women were paid less. At Bristol in 1461, women were accused of contributing to unemployment among weavers: "For as much as divers persons of the weavers' craft hire their wives, daughters, and maidens, to weave in their own looms and men learned in the said craft go vagrant and unoccupied; therefore no weavers from this day forward set, put or hire, his said wife, daughter or maid to weaving on the loom...upon pain of six schillings eight pence, a considerable sum. Once crafts became more regulated into guilds in the later Middle Ages, women gradually were eliminated from those professions regulated by guilds. Men discouraged women from organizing their own crafts into guilds. In a survey circa 1300 in Paris, women participated in eighty-six of the one hundred guilds. Fourteen guilds excluded all women, but seven guilds were exclusively for women, although management was male. At about the same time Cologne had five guilds solely for women whereas London had none. It appears that in Europe no trade was closed to women legally. The only respectable alternative for women was to work within the home economy. It has been determined now that medieval women had more access to high-status and independent employment than women had in later periods of history, basically until the twentieth century. Women worked in a wide-range of jobs. While most women worked as domestic servants and retailers in the towns, all women learned how to spin thread. The distaff was a symbol of this endeavor and had been since the days of the ancient Greeks. Most girls also learned how to weave, but if the cloth was to be sold, then it was usually done by men. We find women also being employed as tanners, skinners, butchers, mercers, grocers, brewers, vintners, fishnet makers, blacksmiths, armorers, prostitutes and bakers. All these occupations are portrayed in illuminated manuscripts from the Middle Ages. Women in some of these positions had apprentices. Not too many woman could get into the baker's guild as they used the specious argument that women were not strong enough to knead the dough. Women in Paris appealed this discrimination and won. A small selection of professions women were employed in will be discussed in more detail. 4 Women were the mainstay of the retail trade. Most all food items, household goods, and clothing were sold by these women. As medieval society was stratified, so too was this occupation. Those that could afford it had their own shop where they would make and sell specific items, like candles and seals, and be called a chandler. Some women rented space, and others hawked their wares from the street corners. These hucksters were not as well respected as the retail traders, and even less flattering were the regrators, who bought goods in the market early in the day and then sold them at a profit later in the day, when scarcity drove up the prices. Customers felt that these regrators and hucksters charged too much, and a popular poem by William Langland, Piers Plowman, relates how the man, Avarice, recalled his wife as Rose the Regrator...she hath holden huckstery all her lifetime. Rose commonly cheated her customers using false weights and sold thinned ale by the cupful to poor people for the price of better-made ale. Unfair business practices did not just begin in the twentieth century. The courts even seemed to have been prejudiced against these regrators, leveling stiffer fines to the women than to the men. Domestic servitude was a common occupation for young girls. They usually signed a multi-year contract to work for a set amount. Some signed ten year contracts, and these maidens could be sued if they left before the contract was finished. Pay was dismal being about 1 pound per year plus room, board, and clothes. Young women were subject to being sexually assaulted by their masters, and if an infant resulted from this, the woman had to give it up to a foundling home or it also could be exposed, a subject of infanticide. Ale and later on beer were imbibed by all in the middle ages. It was usually the women who brewed the ale. Most all women brewed ale for their household's use, and many went into commercial production, producing larger amounts for resale. Women brewsters or ale-wives usually came from the more successful merchant families, at least in England. Lower class women frequently got into trouble with town authorities because they failed to obtain a license, called the assize of ale. Medieval towns regulated all aspects of the brewing process, and women could make a good living as brewsters. Margery Kempe was a successful brewster in King's Lynn before becoming a pilgrim and mystic. Cloth production was the most labor-intensive industry in the middle ages. Over twenty- 5 five different occupations were connected with producing primarily woolen cloth. Women served in all of these, although the most prestigious job was weaving and it was usually reserved for men. Throughout Europe various types of cloth were produced with the raw wool coming from England and Spain. Each town specialized in a particular type and sometimes color. Each step of the cloth industry was highly regulated, and women generally received lower wages than men for the same work. Through the close reading and translation of the custom accounts, it has been found that many women were overseas trading and not just buying wholesale for their large households. Women were actually in the wholesale trade importing and exporting goods to Iceland, France, Spain, Wales and other destinations. Some were widows who continued their husband's business, and others were trading at the same time as their husbands. As women were not to travel far without male companionship, women wholesale merchants usually hired a male buyer to make the purchases abroad. Many towns in England like Bristol, Coventry, London, and Exeter all had women who traded locally, nationally, and internationally in such items as cloth, iron ore, and wine. One of the famous traders was Alice Chestre, who lived in Bristol in the fifteenth century. Initially in business with her husband, after his death her business acumen was demonstrated by her lucrative trade that she carried on for twelve years. For at least a decade, she was responsible for one-fourth of all import and export trade in Bristol, the second largest city after London in the Middle Ages. She was successful enough to purchase ships herself, so she did not have to lease them, and even had the first ship-loading crane constructed at a cost of 41 pounds. Wealthy enough to build a new four-story house on High Street in Bristol, she also spent a considerable amount of money on her parish church, who have maintained her philanthropic endeavors in their written records. In reconstructing the experiences of women healers in the Middle Ages, only two monographs were written on this. Prejudice about women as healers in many ways is based on the modern reconstruction of the history of medicine. Victorian and earlier stereotyping of midwives as fat, dirty, drunken old women was passed from fiction into fact, and by extension included all woman healers of history. All medieval women were expected to know something of medical practices. They were expected to treat wounds, fevers, colds, and contagious diseases. 6 Women served as physicians, surgeons, barber-surgeons, midwives, herbalists, and apothecaries. Physicians were university trained and dealt with general diagnosis using urine samples, feeling the pulse, and consulting astrological charts. Surgeons did bone setting and amputations, while barber-surgeons were largely confined to minor surgical procedures, especially bloodletting. Apothecaries dispensed medications from their herb gardens and other sources besides giving medical advice, antithetical to physicians. An empiric was a generic terms loosely defining all those who practiced on their own, independent of university, licensure and usually guild regulations. Herbalists and leeches came under this category as well as many midwives. Duties of the midwives varied greatly in the middle ages. These various medical care giving categories were more fluid and much cross overing of duties and titles existed in the Middle Ages. Also, few medical practitioners during these centuries relied solely on medicine for their livelihood. So many families could not afford to pay the requisite fees for consulting one of these care givers, especially if they were male, for men charged considerably more than females did. It has also been established that women medical care givers also treated poorer patients, and in some cases purely for charity. Once universities and medical schools were available for training, then women who wanted to be a physician, were slowly eased out because it required a professional education and license, not available to women. As the guilds developed, from the High to Later Middle Ages more specialization occurred in medical care, and the various medical professionals were in separate guilds. While delivery of babies was still strictly reserved for women, over time male physicians realized the lucrative fees that could be obtained for deliveries. When the male physicians espoused the scientific medical rhetoric to a patient, it made the female midwives appear uneducated and not up to the important task of bringing an infant into the world. The oldest and most prestigious medical school in the west was the medical school at Salerno in Southern Italy. Women here not only attended these schools studying medicine and pharmacy, but some were the professors. Dame Trotula was the most famous woman from Salerno. While some scholars doubt her existence, most now agree that she was a real person sometimes between the mid eleventh century and early thirteen century. It appears she was the author of a famous book on the diseases of women, translated into middle English as On the Diseases of Women before, During, and after Childbirth. Even the well-known English author, Geoffrey 7 Chaucer wrote about Trotula, and is a reflection of the long respected position that women held in medicine. We have some documentation from the southern part of Italy, in the Duchy of Calabria, that the Duke was the one to grant the medical license after the candidate was tested by the faculty of medicine at the University of Salerno. Extant is the medieval medical license for Francesca, a new surgeon, which states: "...the law permits women to practice medicine and because it is better, out of consideration for morals and decency, for women rather than men to attend female patients, we grant her the license to heal and to practice, having first received the usual oath from the said Francesca to the effect that she will loyally abide by the traditions of the said art...Naples 10 September 1321." Francesca would have had her own herbal garden to obtain the necessary plants to carry out her medical practice, which would have included blood letting, teeth pulling, and other procedures. Irises, marigolds, peonies, violets, sage, borage, and pulmonaria would have all been part of her flora and fauna. Hildegard of Bingen, was an infirmarian before becoming an abbess in Germany and was renowned for her cures and skill, writing a book on human biology, illnesses, and describe some 485 herbs and plants. This work was the most advanced of the time, and reflects the knowledge available long before Arabic Medical works were translated into Latin in the twelfth century and later. In fact, there are Hildegard of Bingen homeopathic clinics in Germany and America today, attesting to her skill and knowledge of medicine. Midwifery has been practiced by women for thousands of years. Up until the last several centuries, the majority of births were attended by women. Many towns had official midwives. These midwives controlled access to their profession and maintained its standards, including a four-year apprenticeship with very specific rules and regulations. Probably in earlier times and in smaller villages apprenticeships were shorter. These women served as the local doctor or what today would be called a nurse practitioner. Married women with families could not be midwives as the authorities felt they were too busy with their own households. In some places where there was a shortage of women in this profession, the midwives that took in apprentices received a good fee together with free citizenship in the town. Dovetailing these financial benefits, many midwives would get exemption from taxes, a pension, and citizenship. Other rules that these 8 midwives followed were: to threat rich and poor expectant mothers the same, distributing public welfare to poor expecting women, doing the vaginal examinations for the male doctors, giving the annual examinations for leprosy, doing minor surgeries, and backing up other medical people during outbreaks of pestilence and other epidemics. Outside requirements were also given to these care givers. Some towns required them to report all illegitimate children, abortions, and infanticides. If the midwives did not then they could be subject to the same punishment of the perpetrator of the crime: buried alive, burned at the stake, or drowned in a sack. During the labor process, the midwives had a large repertoire of ways to alleviate the pain from secret ingredients to superstitious incantations. In the centuries to follow, it will be these mysterious practices that will help lead to the accusations of witchcraft on the part of midwives. The Textbook of Midwifery, published in the late sixteenth century, stated emphatically that "many midwives were witches and that they offered infants to satan after killing them by thrusting a bodkin into their brains." However, no evidence of this exists. By the twelfth and thirteenth centuries as towns greatly increased in size and prosperity, various medical institutions were established for orphans, lepers, and for the poor, services that today would be called medicare and medicaid. Wealthy merchants and even the nobility established hospitals for the ill, and separate hospitals for lepers outside the town walls. In Paris, St. Catherine's Hospital was founded to take care of poor or sick women. It had only six nuns, whose duties included gathering up drowned corpses from the Seine River, the dead prisoners, and those found dead on the streets. After collecting the bodies, they then took care of burying them. St. Catherine's also served as a short-term lodging for penniless women coming to Paris to seek work, suggesting the medieval equivalent of the YWCA. Poor pregnant women could be housed in these hospitals too. Two hospitals founded in the middle ages are still functioning today: Hotel Dieu in Paris and St. Bartholomew's in London. It was during the Middle Ages that the Augustinian Order of Sisters was founded, whose nuns were mainly in the nursing profession. By the end of the thirteenth century it has been estimated that 200,000 women were serving as nurses within church orders. It was not uncommon for poor mothers, especially single ones, to surreptiously leave without their babies. Other infants were abandoned on the hospitals' doorsteps, at monasteries, and at churches. Because of the scarcity of wet nurses, the nuns 9 attempted to feed the babies using earthenware or tin bottles with a cloth teat. Survival rates were very low, but then this was true for at least the next five hundred years. Too many unwanted babies were abandoned to their fate, and there were not enough personnel and money to care for them. Prostitution was generally legal in the Middle Ages. Mainly municipal but also religious authorities regulated this profession, including the type of clothing a prostitute must or must not wear, where they could ply their trade in the town, and the actual name of the street where they were located. St. Augustine, the Bishop of Hippo in the 5th century, wrote the definitive statement on why prostitution could be allowed: "If you expel prostitutes from society, prostitution will spread everywhere...the prostitutes in town are like sewers in the palace...it was better for a man to have non procreative sex with a prostitute than with his own wife because then he at least would not be corrupting an innocent woman...If you take away the sewers, the whole palace will be filthy." Prostitutes kept licentiousness from spreading all over. Research in medieval Florence, Italy suggests that institutionalization of prostitution was to increase the falling birth rates due to men's homosexuality. For the Church, the prostitute was a contemptible creature not because she posed as a loving woman and had sexual relations with men in return for financial reward, but because her entire life was devoted to the lust of the flesh, which was one of the seven deadly sins. Why did women become prostitutes? The most common reasons were poverty and male violence. The poor included widows with small children, servants sexually abused by a master, and non-residents unable to get legitimate work. In Dijon, France, the town provided young men with opportunities for fornication with prostitutes as a remedy for the epidemic of rape, for in Southeast France groups of young men often practiced sexual violence, what would now be called gang rape, on lower class women. This was an acceptable amusement for young males. These victims were either virginal young girls or young wives with husbands temporarily absent. Once these maidens were deflowered, they were easily recruited by a madame or brothel keeper. Initially prostitutes had to reside outside the town walls, but then they were allowed inside, but restricted from too close of proximity to churches, monasteries, and cemeteries. Paris had an official "red-light" district rather than municipal brothels many towns had in England, and in this 10 case it is though that powerful citizens controlled the brothels, so Paris and other towns did not establish municipal brothels. London relegated prostitutes to only one part of the city in Cock's Lane, but mainly outside of the city in Southwark, the area south of the Thames. The Bishop of Winchester owned this land, so he regulated the brothels. Interesting, the prostitutes were nicknamed "Winchester Geese." Some towns in England forbade prostitution, but their assessment of fines against them indicates a form of licensing fee. Town authorities changed street names to represent colloquially the emotional state of the prostitute. Hot Street was the street name in English towns and Caliente Street in Spain. One enterprising harlot gave herself the name of Juliana Full of Love. If a prostitute would not relocate to the proper street, then her door and windows could be removed. Public bath houses were supposed to be segregated by gender, but often this rule was ignored, and illicit activity occurred. Prostitutes were forbidden to touch food in the marketplace, just like the Jews. In many places prostitutes were forbidden to attend church with or speak to respectable women. In Paris prostitutes solicited clerics who passed them by, but if these clergy did not respond then these women cried out "sodomite". In France there was a special official whose job was to take a fee of two schillings a week from a prostitute to allow her to follow royal armies. His title was King of the Ribalds. Even the Papacy earned income from prostitution. All town authorities had strict rules outlining the clothing regulations. Each town had different rules, and it was important for women traveling to be aware of the certain color that was set aside for the prostitutes. In some areas it might be a red or yellow scarf or gown, and in other places, white or saffron. Yellow and then red seem to be the popular choices for the pigment. Bristol was unique in stipulating a stripped hood. In some towns the height of the prostitutes' heels, and the depth of her decolletage were also measured and regulated. Brothel keepers in one town even had to wear a specific garment, a red hood with a bell attached. Pimps were regulated in many areas too, but they definitely had more advantages than the women. In certain places brothel keepers could sell prostitutes to another brothel or pawn them. Parents in some places could sell their daughters to brothel keepers. Many prostitutes were able to save enough to provide themselves with an adequate dowry to marry a respectable man. Detailed explanations have been given of women's work in the middle ages because 11 women will continue their involvement in these occupations until the Industrial Revolution, circa the nineteenth century. While opportunities will increase or lessen as the economy fluctuates, women were employed in a wide variety of professions, and were an essential part of the medieval economy in the towns and in the countryside.