MAR Strategic Plan

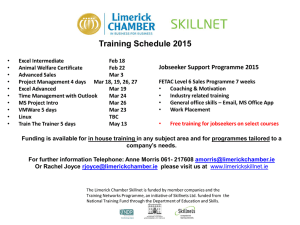

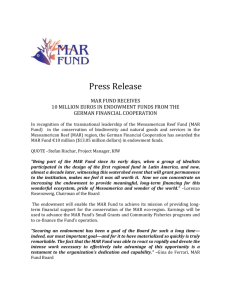

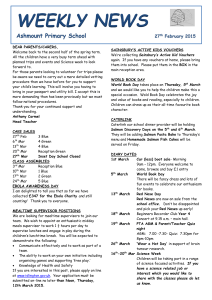

advertisement