Syndrome of fever in surgical infection

advertisement

MINISTRY OF HELTHCARE OF THE REPUBLIC OF UZBEKISTAN

TASKENT MEDICAL ACADEMY

APPROVED

Vice-rector for studying process

Senior Prof.

Teshaev O.R.

«_________» __________2011y

Lecture

For students of VII course of treatment faculty

By theme

FEVER SYNDROME AT SURGICAL INFECTIONS

Written on basis of tutorial

Tashkent 2011

2

APPROVED

On conference in department of surgical diseases for general practitioners

Head of department___________________senior prof Teshaev O.R.

Text of lecture accepted by CMC for GP of Tashkent Medical Academy

Report №___________from____________2011 y

Moderator senior professor Rustamova M.T.

3

Theme: FEVER syndrome AT sURGICAL INFECTIONs

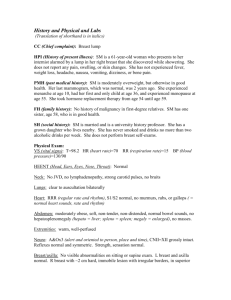

Right at the beginning of sharp diseases of a stomach{belly} the fever arises seldom. It is necessary

to measure temperature in a direct gut by the thermometer in a special environment, or by means of

катетера for a pulmonary artery. The temperature in an oral cavity also can be informative enough,

but is less reliable parameter. The temperature in an axillary hollow usually does not give the

necessary information, therefore it{her} do not measure. The normal body temperature at many

patients does not exceed 98,60F (37,00С). The fever above 990F (37,20С) has the certain clinical

value and should draw attention of the doctor. Rise in temperature of a body can accompany with

any inflammatory process in an organism, but is rather late symptom. At patients with

гангренозным аппендицитом before development of punching the moderate rise in temperature

can be observed only. Rise in temperature of a body not always testifies to connection of a bacterial

infection. The fever in a combination to a fever is usually observed бактериемии and is the

indication to performance of bacterial crop of blood and search of a source of this бактериемии.

The degree of rise in temperature can matter at differential diagnostics. For example, for the

beginning sharp аппендицита the high fever is not characteristic. The body temperature above

1020F (38,90С) is marked{celebrated} at a bacterial peritonitis, сальпингите, a pyelonephritis and

a pneumonia. The high peaks of temperature defined{determined} at a time of day (in the form of a

characteristic paling), arise at formation of abscesses of a belly cavity. In general it is possible to

consider{count}, that at patients with pains in a stomach{belly} the above a fever, the disease is

heavier. It is necessary to remind, that the fever and pains in a stomach{belly} not always show the

diseases demanding operative intervention (for example, a family Mediterranean fever). However

variability of temperature reaction at various diseases of bodies of a belly cavity is so great what to

diagnose, or, on the contrary, to exclude any disease only on the basis of a temperature curve it is

impossible. At the dehydrated patients or patients of advanced age temperature reaction to

pyoinflammatory diseases can be insignificant or be absent. At small children, on the contrary, the

high fever is observed often enough at not heavy diseases. Гипотермия attention of doctors as at the

septic phenomena can be прогностически more significant, than the fever also should draw.

Purposes{assignments;destinations} of antibiotics should be avoided until the reason of a fever if

only антибиотикотерапия is not the compelled{forced} measure for decrease{reduction} in a body

temperature is found out.

4

The Breast

Lymphatic drainage

The lymphatic drainage of the breast is important, but there Is in no mistique about it; as

with any other organ, its lymph drainage follows the pathway its blood supply and therefore travels.

1. Along the tributaries of the axillary vessels to the axillary lymph nodes.

2. Along the perforating branches of the internal thoracic vessels, which pierce each

intercostal space, to the lymph nodes along the Internal thoracic chain. These lymph nodes also

receive lymphatics which accompany the lateral perforating branches of the intercostal vessels.

Although the lymph vessels lying between the lobules of breast communicate freely, there is

a tendency for the lateral part of the breast to drain towards the axilla, and the medial part to be

served by the internal thoracic chain.

A subareolar plexus of lymphatics below the nipple (the plexus of Sappey) and another deep

plexus on the pectoral fascia have, in the past, being considered to be the central points to which the

superficial and deep parts of the breast drain before passing to the main efferent lymphatics. These

plexuses are, however, relatively unimportant, the main drainage proceeding directly to the regional

lymph nodes.

The axillary lymph nodes drain the pectoral region, upper abdominal wall and the upper

limb in addition to the lymphatics of the breast, and are arranged in five groups.

1. Anterior: lying deep to pectoralis major.

2. Posterior: along the subscapular vessels.

3. Lateral: along the axillary vein.

4. Central: within the axillary vein.

5. Apical: immediately behind the clavicle at the apex of the axilla-receiving lymph from all

the other axillary nodes.

The subclavian lymph trunk emerges from the apical nodes. On the left this trunk usually

drains directly into the thoracic duct; on the right it either empties directly into the subclavian vein

or else joins the right jugular trunk.

Lymphatic spread of a growth in the breast may occur further afield when these normal

pathways have become interrupted by malignant infiltration, surgical ablation or radiotherapy.

Deposits may then be found in the limphatics of the opposite breast or opposite axilla, the groin

lymph nodes (via lymph vessels in trunk wall), the cervical nodes (as a result of retrograde

extension from the blocked thoracic duct or jugular trunk) or intraperitoneal lymphatics as

retrograde spread from the lower internal thoracic nodes.

Symptoms of breast disease

There are three common symptoms of breast disease; a lump, bleeding or discharge from the

nipple, and pain.

A lump in the breast

Ninety-five per cent of all lumps in the breast will be one of the four following.

1. Carcinoma of the breast.

2. Cyst.

3. Fibroadenoma.

4. A localized area of fibroadenosis.

In addition, the following possible causes need to be considered.

1. Traumatic: fat necrosis.

2. Other cysts.

a) galactocele

b) chronic abscess

c) cystadenoma

d) retention cyst of the glands of Montgomery

5

3. Other tumours.

a) sarcoma (extremely rare)

b) duct papilloma

4. Swellings arising from the chest wall.

a) tuberculosis or tumour of a rib

b) llpoma

c) eroding aortic aneurysm

d) cold abscess (empyema necessitatis)

f) thrombosis of superficial veins of breast or chest wall (Mondor's disease).

Although useful Information can be derived about a lump in the breast by careful

examination, it is a good clinical rule that any discrete lump in the breast must be excised for

histological examination or aspirated for cytologlcal examination: 'No lady should have a lump in

the breast.'

If the lump is considered likely to be a cyst, it is safe practice to aspirate it to confirm the

diagnosis. If it disappears, no further treatment is required. However, if no fluid is obtained, the

lump should be surgically removed or submitted to fine needle aspiration and cytologlcal

examination of the material obtained.

Disharge from the nipple

It may be.

1. Bloodstalned.

a) duct papilloma

b) Intraduct carcinoma

c) Paget's disease

d) Invasive carcinoma (unusual)

2. Serous: Early pregnancy.

3. Yellowish, brown or green: flbroadenosls.

4. Mlky: following lactation

5. Purulent: breast abscess.

It is the first, the bloodstained discharge, which alarms the patient. Its management is as

follows.

The patient is carefully examined; there may be one of the following possibilities:

1. A mass is discovered, pressure on which produces the discharge; the mass is excised and

further treatment is based on the result of histological examination.

2. If a mass is not discovered, it may be possible by pressing on one spot adjacent to the

nipple to obtain a discharge. This segment of the breast is surgically explored and submitted to

histological examination; again a limited or more extensive operation may be required, depending

on the results of hystological examination. It is, however, very rare for a malignant condition to be

present without a lump having been detected.

3. If no mass can be felt and no duct can be incriminated, a conservative approach is

adopted; the patient is kept under supervision either until the site of discharge is located and

excised, or the bleeding ceases; again, this is most unlikely to be the presentation of malignant

disease of the breast.

Special investigations which may help are a mammogram and a 'ductogram`, performed by

injecting contrast into the discharging duct.

Pain in the breast.

The possible causes to be considered are.

1. Breast abscess.

6

2. Fibroadenosis: typically the pain is present immediately before each period.

3. Carcinoma of the breast: this occasionally gives rise to a 'pricking pain`.

4. Lesions, not of the breast, but of the chest wall, e.g. chondritis of the coastal cartilage.

This syndrome (Tietze's disease) is of unknown etiology, aftects one or more of the 2nd, 3rd or 4th

costo-chondral junctions and, left alone, resolves over a number of months.

TRAUMATIC FAT NECROSIS

Pathology

Disrupted fat cells released by trauma produce a foreign body giant cell reaction with

subsequent fibrosis and perhaps calcification.

Clinical features

Many women presenting with a lump in the breast attribute this to injury. A clinical

diagnosis of fat necrosis should only be made when the trauma was sufficient to cause bruising of

the breast and when the patient is obese. The lump itself may have become smaller in size and this

again would suggest non-malignant condition, in spite of the fact that clinically the lump may be

tethered to the skin and accompanied by large axillary lymph nodes.

Treatment

This is excision since it is impossible to be quite certain of the diagnosis without biopsy: a

section through the lump reveals a pale, fibrous mass which may contain Central fluid fat or chalky

material.

ACUTE INFLAMMATIONS OF THE BREAST

Classification

1. Mastitis of the newborn | probably hormonal but may

2. Mastitis of puberty | proceed to suppuration.

3. Mumps mastitis: rare complication.

4. Traumatic (due to the chafing of braces, etc.).

5. Subareolar: from infection of one of the glands of Montgomery which are sebaceous-like

glands around the areola.

6. Acute bacterial mastitis and acute mammary abscess.

The last cause is the commonest and most important. The majority occur during lactation,

caused either by invasion by Staphylococcus aureus through in abrasion of the nipple resulting in a

circumareolar abscess, or along the milk ducts themselves, producing a deep intramammary

infection. Typically it affects mothers in the first month after their first pregnancy. Breast abscess

may also occur in non-lactating women, but it is a rarity after the menopause.

Clinical features

The infection commences as a cellulitis which localizes into an abscess after several days.

Treatment

Milk engorgement is relieved by manual expression or a breast pump. It is best to stop

lactation with stilboestrol 10 mg daily for 1 week. If the patient is seen within the first 24 hours of

the onset, when the condition is still a spreading cellulltis of the breast, infection may be aborted by

antibiotic therapy. If the infection has been present for more than a day or two it is almost certain

that a localized abscess will have commenced to form. In these circumstances it is best to be oldfashioned and apply poultices which comfort the patient until a localized fluctuant mass forms

which can then be drained. If chemotherapy Is persisted with in these later cases, an unpleasant

condition may result of chronic and recurrent abscesses burrowing through the breast.

7

CHRONIC ABSCESS OF THE BREAST

Tuberculosis, gumma and actinomycosis of the breast are all very rare. The most likely

chronic abscess of the breast is one following prolonged and misguided chemotherapy in the

treatment of acute breast abscess ('antibioticoma' or `penicllllnoma').

FIBROADENOSIS, 'CHRONIC MASTITIS', OR CHRONIC PLASTIC MASTITIS

This is the commonest of all breast conditions. Indeed, some degree of fibroadenosis is

probably present in most women.

Etiology.

Any organ in the body which undergoes cyclical changes of proliferation and regression is

prone to abnormalities of this process; these are the prostate, thyroid and ovary as well as the breast.

Fibroadenosis is found in women from puberty to menopause, after which it only occurs

occasionally in the form of large cysts within the breast. It is frequently bilateral.

Pathology

Macroscopically

The affected breast tissue is tough, yellowish white and of india-rubber consistency. It is not

encapsulated. Cysts are usually present and vary from numerous tiny ones to solitary, large, blue

domed cysts (of Bloodgood). The cyst fluid may be yellow, green or brown in colour. Sometimes

the ducts contain toothpaste-like material.

Microscopically

The main features are.

1. Glandular hyperplasla.

2. Connective tissue hyperplasia.

3. Cyst formation.

4. Papillary formation within cysts.

5. Lymphocytic infiltration.

(It is this lymphocytic infiltration which induced the early microscopists to label this

condition 'chronic mastitis'.)

It is probable that duct papilloma is in essence a localized form of the papillarv formation

seen in chronic mastitis, and that flbroadenoma is a localized glandular and connective tissue

hyperplasia.

Clinical features

The patient, who may be of any age from teens to the menopause, may present with one or

more of the following: a lump in the breast, pain in the breast, particularly before the periods, or

discharge from the nipple, which may bloodstained, yellow, green or brown.

Examination may reveal diffuse lumpiness of both breasts or a mass confined to one sector

of the breast, particularly the upper, outer quadrant. It is characteristic that this lumpiness is best

defined by palpation between the index finger and the thumb, and it is more difficult to feel with the

flat of the hand (in contrast to a carcinoma – symptom of Konig). This is because the segment of

flbroadenosis has almost the same consistency as the surrounding breast tissue.

Less commonly the patient presents with a local, smooth, spherical lump in in the breast

which may be of considerable size. It may be possible to elicit fluctuation or transillumination in

such a lump, and then to be tolerably certain thai the diagnosis is a cyst. Quite commonly shotty

nodes are palpable in the axilla.

Differential diagnosis

8

The differential diagnosis from an early carcinoma of the breast may be very difficult,

indeed impossible; moreover, it is far from rare to find both conditions present within the same

breast, although there is no definite evidence that flbroadenosis is premalignant. It is sound practice

therefore to submit every localized mass in the breast to biopsy, either by needle aspiration or

excision.

Special investigation

A soft tissue X-ray of the breast (mammography) may be helpful in revealing a small

malignant lesion which typically shows an area of speckled calcification. It may also be helpful in

reassuring the patient that a lesion is benign. It must be stressed, however, that errors may occur

even in the most expert interpretation of these X-rays so that biopsy is the safest policy in any

doubtful case.

Treatment

The golden rule is that "no lady is allowed to have a lump in her breast'.

A discrete lump which may be a cyst is subjected to immediate aspiration under local

anaesthetic in the out-patient clinic. If clear fluid is obtained and the lump completely disappears,

we can be certain that it is a simple cyst. The rare condition of a carcinoma in the wall of a cyst

(cystadenocarcinoma) will yield blood-stained fluid on aspiration and a persistent lump can still be

felt; urgent excision biopsy is then necessary.

If no fluid is obtained, a tissue diagnosis must be made. This is performed either by excision

biopsy or by fine needle aspiration and cytological examination. Should this prove to be an area of

benign flbroadenosis, the patient is reassured and suitable follow-up arranged. If a flbroadenoma is

confirmed, local excision is all that is necessary. If the biopsy proves to be a carcinoma, slate

further treatment.

The patients who are not submitted to surgery are the large group of women with diffuse

granularity of one or, more usually, both breasts with no localized mass. A mammogram is helpful,

particularly in post-menopausal women, but usually the patient can be reassured that there is no

evidence of malignant disease and kept under supervision in the out-patient clinic. Monthly selfexamination can also be taught and the patient advised to report if she find any discrete lump.

Many patients with fibroadenosis complain of pain in the breasts, which may or may not be

cyclical. Most can be managed by reassurance and analgesics.

Severe cyclical breast pain may require treatment with the prolactin inhibitor bromocriptine

or with danazol, which inhibites gonadotrophin release. Both, however, may have quite unpleasant

side effects (mastodinyne).

Tumours OF THE BREAST

Classification

Benign

1. ftbroadenoma.

2. intraduct papilloma.

Malignant

1. Primary.

a) carcinoma

b) intraduct carcinoma

c) Paget's disease of the nipple

d) fibrosarcoma

2. Secondary.

a) direct invasion from tumours of the chest wall

b) metastatic deposits from melanoma

9

FIBROADENOMA

Pathology

This is a firm, encapsulated, benign tumour with a whorled appearance on cut surface.

Microscopically it comprises fibrous tissue surrounding epithelial duct proliferation.

Clinical features

Fibroadenomas occur after the age of puberty, commonly in young women; they are highly

mobile 'breast mice' which are not attached to the skin. Rarely in middle-aged or elderly women a

very large lobular fibroadenoma may be found which may even ulcerate the overlying skin by

pressure necrosis (serocystic disease of Brodie). The majority of these remain benign, but a few

may undergo sarcomatous change.

Treatment

Excision and histological confirmation of the diagnosis.

DUCT PAPILLOMA

This may be part of a generalized papillomatosis or may occur as a solitary entity.

The duct papilloma is usually situated in one of the 15 to 20 ducts near the nipple In a young

woman. The patient complains of bleeding from the nipple and the examiner may either find a small

elliptical swelling adjacent to the nipple, pressure on which produces this discharge, or he may

merely find that pressure on one spot causes blood to emerge from the mouth of the duct.

An X-ray 'ductogram' may define the lesion.

Treatment

Excision of the lump with, of course, histological examination of the specimen, or. if no

lump can be felt, excision of the small segment of breast tissue from which the discharge can be

expressed.

CARCINOMA

Pathology

This is an immensely important subject - the commonest malignant disease of females in the

United Kingdom, accounting for about 13 000 deaths annually In England and Wales; less than 1

per cent occur in men. Any age may be affected, but it is rare below the age of 30.

There is no definite evidence of any predisposing factors in humans, but there is a familial

tendency; It is rare in orientals and less likely to affect women who have had pregnancies in their

teens. There is no proved association with the contraceptive pill.

Clinical and macroscopic types

1. Scirrhous: hard and encapsulated; the cut surface is grey, concave, gritty and with white

spots resembling an unripe pear.

2. Atrophic scirrous; scar-like tumour occurring in the shrivelled breast of the elderly.

3. Encepnaloid; large, soft and 'brain-like'.

4. Papillary: intraduct or intracystic.

5. Lactational: a fulminating form occurring in or after pregnancy ('mastitis carcinomatosa').

6. Paget's disease of the nipple.

Microscopic classification

Carcinomas of the breast are all derived from ductal or alveolar epithelium. They may be

classified as follows.

1. Adenocarcinoma: well-differentiated acini in a fibrous stroma.

10

2. Spheroidal cell: clumps of spheroidal cells in a fibrous stroma.

3. Carcinoma simplex: (anaplastic carcinoma) undifferentiated cells arranged in solid

masses.

4. Colloid or mucold carcinoma: where excessive mucus production is a feature.

5. Intraduct carcinoma: arising in a duct and invading its wall.

6. Papllary cystadenocarcinoma; arising in a cyst wall.

7. Squamous cell: arising in squamous metaplasia, usually in a cyst wall.

8. Paget's disease. Lobular carcinoma in situ: a premalignant condition, often present in both

breasts.

Spread

1. Direct extension: involvement of skin and subcutaneous tissues leads to skin dimpling,

retraction of the nipple and eventually ulceration. Extension deeply involves pectoralis major,

serratus anterior and eventually the chest wall.

2. Lymphatic: blockage of dermal lymphatics leads to cutaneous oedema pitted by the

orifices of the sweat ducts, giving the appearance of peau d'orange. Dermal lymphatic invasion

produces daughter skin nodules and eventually 'cancer en culrasse', the whole chest wall becoming

a firm mass of tumour tissue. The main lymph channels pass directly to the axillary and internal

thoracic lymph nodes. Later spread occurs to the supraclavlcular, abdominal, mediastinal, groin,

and opposite axillary nodes.

3. Blood spread: especially to lungs, liver and bones (at the sites of red bone marrow, i.e.

skull, vertebrae, pelvis, ribs, sternum, upper end of femur and upper end of humerus). The brain,

ovaries and adrenals are also frequent foci of deposits.

4. Trans-coelomic: pleural and peritoneal seeding occurs commonly in advanced disease,

accompanied by pleural effusion and ascites respectively.

Staging

The following clinical staging is in common use (Fig.).

I. The lump is confined to the breast, with or without some degree of skin fixation to it or

with indrawtng of the nipple.

II. As above, but in addition, the axillary lymph nodes are enlarged and quite mobile.

Ill. The tumour and/or the nodes are fixed superficially or deeply.

IV. Distant metastases are present.

There is a high degree of clinical error, about 25 per cent in fact, in estimating whether a

tumour is stage I or II; axillary lymph nodes may be involved although they cannot be felt,

conversely axillary nodes which are palpable may prove free

Fig. 1. The clinical staging of breast cancer.

from tumour. However, the classification is of great practical Importance since patients with

stage 1 and II lesions are usually submitted to 'curative' surgery, whereas those in stages III and IV

are only suitable for palliative treatment (see section on treatment below).

TNM classification

There are considerable variations in the classification of malignant tumours which makes

exchange of information between centres difficult. The International Union against Cancer has

devised a clinical system for staging tumours which has already been applied to most sites. The

Initial letters TNM stand for: T — the tumour, N — the regional lymph nodes and M — distant

metastases. The addition of numbers of the three components indicates different degrees of extent

of the malignant process.

The classification applied to the breast is as follows:

T — Primary tumour

T0: no evidence of primary tumour.

11

T1: the tumour is 2 cm or less in diameter, skin not involved, except in the case of the

Paget's disease where confined to the nipple; no nipple retraction or fixation to underlying tissues.

T2: tumour more than 2 cm but not more than 5 cm In diameter, or incomplete skin fixation

with tethering or dimpling of the overlying skin, or nipple retraction, but no fixation to underlying

tissues.

T3: tumour more than 5 cm but not more than 10 cm in diameter, nor infiltration nor

ulceration of the skin or peau d'orange or fixation to the pectoral muscles.

T4: tumour of more than 10 cm diameter or skin involvement or peau d'orange wide of the

tumour or fixation to the chest wall.

N — Regional lymph nodes

NO: no palpable homolateral axillary nodes.

NI: palpable, mobile homolateral axillary nodes.

N2: homolateral axillary nodes fixed to one another or to other structures.

N3: homolateral supra- or infraclavicular nodes movable or fixed, or oedema of the arm.

M — Distant metastases.

MO: no evidence of distant metastases. (This includes X-rays of the chest and skeleton,

bone scan and liver ultrasound).

MI: distant metastases present, Including skin involvement wide of the breast, involvement

of contralateral nodes or breast, and clinical, scanning or X-ray evidence of spread to lungs, pleural

cavity, skeleton, liver etc.

Clinical features

The patient may present with local symptoms, usually a painless lump in the breast

(although occasionally a pricking discomfort is complained of). Sometimes the principal complaint

is of recent indrawing of the nipple or of bloodstained discharge. In addition, a small percentage of

patients present with symptoms produced by secondaries, for example backache, pathological

fracture, or dyspnoea from lung and pleural involvement.

Examination of a patient with a lump in the breast must be carried out in an orderly manner.

The breasts are Inspected for evidence of nipple elevation or retraction, or of skin fixation to

the underlying tumour; the-latter is then checked by gently moving the lump within the breast.

Recent nipple retraction is very suggestive of malignant disease, but the nipple may have been

indrawn since birth or following a previous acute infection. Skin fixation is also strong supporting

evidence of carcinoma, although it may be seen rarely over an area of chronic mastitis and may

accompany fat necrosis or follow chronic abscess.

Palpation commences first with the normal breast. The diseased breast is then examined, the

clinical features of the lump being determined with especial reference to skin attachment and deep

fixation. The axillary nodes and then all other lymph node areas are palpated. A search is made of

the other foci of possible distant spread; examine the chest, palpate the liver, test for the presence of

ascites and examine the pelvis.

Investigations

The chest is X-rayed and a radiological and bone scan skeletal survey of skull, spine and

pelvis is performed for secondary deposits.

A full blood count is performed, since anaemia and leucopenia suggest widespread bone

marrow Involvement.

Diagnosis is confirmed by fine needle aspiration or biopsy.

Treatment – one word – "COMPLEX".

Stages I and II

When the disease is clinically confined to the breast tissue alone or has only involved the

axillary lymph nodes with no evidence of either spread into adjacent tissues, or of widespread

12

dissemination, the surgeon hopes to be able to eradicate the disease and achieve a 'cure'.

Unfortunately, in a proportion of these patients, microscopic metastases will already have occurred

and so evidence of dissemination may become manifest months or years after the primary tumour

has been removed. There is wide variation in the treatment of these cases in different centres.

Surgery ranges from, at one end of the spectrum, removal of the lump only, through simple

mastectomy, mastectomy with clearance of the axillary nodes (Patey), radical mastectomy in which

the pectoral muscles are removed (Halstead), to, at the other extreme, radical mastectomy combined

with excision of the internal thorach chain. There is no uniformity of opinion as to whether any of

these method should be combined with either pre- or post-operative irradiation or whether or not the

ovaries should be either ablated or irradiated in pre-menopausal patients The reason for this

controversy is the rarity, to date, of carefully controlled clinical trials comparing the results of these

various combinations of therapy. Such trials have now shown that no form of local treatment has

any advantage over the other as regards patient survival.

Current opinion favours a relatively conservative approach. Most surgeons perform either

simple mastectomy with clearance of the axilla, or else local removal of the tumour ('lumpectomy')

combined with radiotherapy; the latter has the great advantage of an excellent cosmetic result and

long-term studies indicate that life expectation and local tumour control are as good for this

technique as for more radical mutilating surgery.

Because of the relatively poor prognosis in advanced stage II disease (those with extensive

lymph node involvement), suggesting that in 60 per cent of these patients occult dissemination of

tumour has already occurred at the time of presentation, there is particular interest in the trials in

progress on the value of adjuvant cytotoxic or hormonal therapy in this group.

Stage III cases.

Surgical clearance of the disease is now impossible. Neoadjuvant therapy (local

radiotherapy or/and chemotherapy before operation) often produces useful palliative results

although a 'toilet, sanitary' operation may later be required to remove a fungating and ulcerating

local lesion.

Stage IV and recurrences after previous mastectomy

A solitary distant deposit, for example in one bone, or local recurrence in the scar following

mastectomy, is best treated by local radiotherapy.

Topical injection of a cytotoxic may be used in the treatment of malignant ascites or pleural

effusion after preliminary aspiration of the fluid.

Where dissemination is widespread, sex hormones or 'hormone surgery' are used. About 30

per cent of all breast tumours are hormone dependent. The tumour estrogen receptor assay, at

present only performed at special referral centres, is helpful in predicting the likelihood of response.

ER positive tumours respond to hormone therapy in 60 per cent of cases, whereas ER negative

tumours are rarely hormone dependent (10 per cent). Hopefully refinement of this type of assay will

enable more accurate assessment to be made in the future.

There are several methods of hormone therapy available Tamoxifen, a potent anti-oestrogen,

has a low incidence of side-effects and should be the first line of treatment in both pre- and postmenopausal patients.

Patients who do not respond to Tamoxifen are managed.

1. If the pre-menopausal or early post-menopausal: ovarian ablation, either by

oophorectomy (laparoscopic) or radiotherapy.

2. Post-menopausal women: either stilboestrol or ethinyl-oestradiol.

3. Bilateral adrenalectomy (laparoscopic).

4. Hypophysectomy.

These last two major surgical procedures are now rarely employed and have been replaced

by.

13

5. Pharmacological adrenalectomy, which may be effected by means of Aminoglutethimide,

which inhibits synthesis of cortisol and adrenal androgen and estrogen.

In patients with widespread disease not responding to hormone therapy temporary

regression may be effected by means of cytotoxic drugs, particularly in the form of combination

therapy.

Pregnancy and breast cancer

Fortunately carcinoma of the breast occurs rarely during pregnancy and lactation. The

disease process, presumably because of hormonal effects, may be considerably accelerated with the

appearance of an inflammatory type of lesion, the so-called mastitis carcinomatosa. In most cases,

however, the tumour behaves llke a cancer of the same stage in a non-pregnant woman.

Although the prognosis is serious it is not necessarily hopeless. Treatment is carried out

along the lines already indicated according to the stage at which the disease presents. Most surgeons

advise termination of the pregnancy.

Carcinoma of the male breast.

The amount of patient was a little increased per the last years in connection with treatment

of a cancer of a prostate gland antitestosteronic drugs.

This accounts for less than 1 per cent of all cases of breast cancer. The prognosis worse than

in the female, probably because of the sparse amount of breast tissue present, which allows rapid

dissemlnation of the growth into the regional lymphatics.

Treatment consists of radical mastectomy, but since so little skin is available it is often

necessary to carry out a skin graft to the cover the resulting cutaneous defect.

Orchidetomy and cytotoxic therapy may be employed in advanced cases with disseminated

disease.

Prognosis

The 5-year survival rate in stage I tumours is approximately 80 per cent; stage II lesions

approximately 40 per cent. A small number of stage III and IV growths may also have prolonged

survival, especially if slow growing or hormonally dependent.

In addition to the staging of the tumour, histological grading is also of great importance; the

less differentiated the tumour, the worse the prognosis.

PAGET'S DISEASE OF THE NIPPLE

Paget described diseases of bone, penis and nipple, all of which bear his name.

Pathology

The nipple lesion occurs in middle-aged and elderly women. It presents as a unilateral red,

bleeding, eczematous lesion of the nipple which is eventually destroyed. It is associated with a

carcinoma of the underlying breast which may not form a palpable mass.

Microscopic appearance

The epithelium of the nipple is thickened with prolongations of the rete pegs. The deeper

layers of the epithelium contain multiple clear Paget cells with small dark-staining nuclei; these are

hydropic malignant cells. The underlying dermis contains an inflammatory cellular infiltration.

Careful search of the breast after mastectomy usually reveals the presence of an associated

intraduct carcinoma, even if this was clinically impalpable and some distance from the nipple.

Etiology

Paget's disease probably represents the invasion of the nipple by malignant cells arising in a

duct which also gave origin to the associated breast tumour.

14

Treatment

Mastectomy or local excision with post-operative radiotherapy. In the absence of a palpable

mass the prognosis is excellent. When a mass is present the prognosis resembles carcinoma of the

breast in general and depends on the stage of the tumour and its histological grade.

BREAST SCREENING

Since micrometastases are frequently present when only a small lump can be detected by

palpation, much effort has been devoted to discover breast cancer before there is a lump. A

nationwide mammography breast screening is now in progress in the UK. All women between 50

and 65 are offered mammography every three years. A suspicious lesion on X-ray that cannot be

felt has to be localized by 3 dimensional radiography and a wire inserted into the radiological

abnormal tissue so that the surgeon can remove the area by local excision and confirm that the

specimen is the correct portion of breast by X-ray. Then histological examination will establish the

diagnosis. If carcinoma is found, management is as for Stage I tumours outlined above. Early data

from screen trials indicate a pickup of 1 suspicious mammogram in 1000 and of these selected

cases, 50 percent are malignant. It Is hoped that this-early detection will be rewarded by a

significant Improvement in survival and that the expensive screening process does not In itself

cause harm from the radiation exposure.

The Thyroid

CONGENITAL THYROID ANOMALIES

The embryological line of descent of the thyroid gland, from the region of the foramen

caecum of the tongue to its normal position in the neck, may be the site of fistula or cyst formation

(Fig. 1). Rarely the thyroid fails to descend properly into the neck and such a patient may present

with a lump at the foramen caecum (lingual goiter) or at the front of the neck near the body of the

hyoid bone. Such a swelling may not be suspected as being thyroid and if this is removed the

patient may have no other functioning thyroid tissue. In all cases of unexplained nodules in the line

of thyroid descent, a radio-iodine scan should be performed to ensure that there is normal thyroid

tissue present in the correct place before the lump is removed. Occasionally the thyroid descends

beyond its normal station superior mediastinum — a retrosternal thyroid.

THYROGLOSSAL FISTULA

This presents as an orifice in the line of the thyroid descent, in the midllne of the neck. It

may discharge thin, glairy fluid and attacks of infection can occur.

1. – lingual hyoid

2. – suprahyoid thyreoglossal cyst

3. – track of thyroid descent and of a thyreoglossal fistula

4. – thyroglossal cyst or ectopic thyroid

5. – pyramidal lobe

6. - retrosternal goiter

Fig. 1. The descent of the thyroid, showing possible sites of ectopic thyroid tissue or

thyroglossal cysts, and also the course of a thyroglossal fistula. (The arrow show tin further descent

of the thyroid which may take place retrosternally into the superior mediastinum).

Treatment

The treatment is to excise the fistula and this excision must be complete. The track runs in

close relationship with the body of the hyoid, therefore this should be removed in addition to the

fistula and the dissection is continued up to the region of the foramen caecum of the tongue.

THYROGLOSSAL CYST

15

Forms in the embryological remnants of the thyroid and presents as a fluctuant swelling in

the midllne of the neck. Clinically the cyst moves upwards when the patient protrudes the tongue

because of its attachment to the tract of the thyroid descent and moves on swallowing because of its

attachment to the larynx by the pretracheal fascia.

Treatment

Such cysts should be removed surgically.

THYROID PHYSIOLOGY

The thyrold gland is concerned with the synthesis of the iodine containing hormones

thyroxine (tetra-iodothyronine, T4) and tri-iodothyronlne (T3) which control the metabolic rate of

the body. It also secretes calcitonin from its parafollicular C-cells, which reduces the level of serum

calcium and is therefore antagonistic to parathormone.

Iodine in the diet is absorbed into the blood stream as iodide which is taken up avidly by the

thyroid gland. After entering the follicle, the iodide is converted into organic Iodine which is then

bound with the tyrosine radicals of thyroglobulln to form the precursors of the thyroid hormones.

The colloid within the thyroid vesicles composed of thyroglobulin synthesized in the follicular cells.

Within thyroglobulin, iodine and tyrosine combine first to form mono-iodotyrosine from which T3

and T4 are formed and stored within the thyroglobulin colloid. These hormones are released into the

blood stream after being separated from thyroglobulin within the follicular cells. In the general

circulation about 99 per cent of T3 and T4 Is bound to protein (protein-bound iodine) and it is the

minute amount of unattached thyroid hormones in the circulating blood which produces the

endocrine effects of the thyroid gland.

The concentration of the thyroid hormones in the blood under normal conditions is

maintained within narrow limits. The immediate control of synthesis and liberation of T3 and T4 is

by the thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) produced by the anterior pituitary. TSH is secreted in

response to the level of thyroid hormones in the blood by a negative feedback mechanism so that a

drop in the level of these hormones stimulates TSH production and vice versa. The secretion of

TSH is also under the influence of the hypothalamic thyrotrophln-releasing hormone (TRH).

The production of thyroid hormones can be inhibited by the thiouracils and mercazolilum

which block the binding of iodine but do not Interfere with the uptake of iodide by the gland.

Although less T3 and T4 are produced, the thyroid gland tends to become large and vascular with

treatment by these drugs.

High doses of iodide given to patients with excessive thyroid hormone production result in

an increase in the amount of iodine-rich colloid, and a diminish liberation of thyroid hormones; the

gland also becomes less vascular. The effects of Iodide treatment are maximal after two weeks of

treatment and then diminish.

Lack of iodine in the diet prevents the formation of thyroid hormones and excess pituitary

TSH Is produced which may result in an iodine deficient goiter. Thiocyanates prevent the thyroid

gland from taking up iodide.

PATHOLOGY OF GOITER

Nodular goiter

Like the breast, ovary and the prostate, the thyroid gland undergoes periods of activity and

regression at different times. There is excessive thyroid activity at puberty and during pregnancy

and a fall after the menopause. The commonest cause of enlargement of the thyroid gland in Great

Britain is a nodular goiter and this has similarities with the commonest pathological conditions of

the breast and prostate, namely fibroadenosis and benign hyperplasia. In a nodular goiter, gland is

enlarged, irregular and partly cystic. The pathology would appear to be an excessive degree of

activity and regression resulting in a varied appearance of the gland, some vesicles are lined with

hyperactive epithelium and others with flattened atrophic cells. Some contain no colloid, others an

excessive amount. The thyroid interstitium is excessive with a certain amount of fibrosis and round

16

cell infiltration. Nodular goiters may produce a normal amount of thyroxine, but sometimes

excessive thyroxine production results in hyperthyroidism in this condition ('secondary

thyrotoxicosis').

Complications of nodular goiter

1. Tracheal displacement or compression.

2. Haemorrhage into a cyst (which may produce urgent tracheal compression).

3. Toxic change.

4. Malignant change (rare).

Colloid goiter

All diseases of the thyroid are commoner in geographical locations in which the water and

diet are low in iodine. In Great Britain the most notorious district was Derbyshire and the frequency

of goiters in this region gave rise to term 'Derbyshire neck'. Iodination of table salt has all but

abolished this state of affairs. Tadjikistan, Switzerland, Nepal, Ethiopia and Peru are also areas

where natural iodine is very scarce in the diet and water, and there thyroid disease is common. The

commonest lesion of the thyroid gland due to iodine deficiency is the colloid goiter in which the

gland as enlarged and the acini are atrophic with a large amount of colloid. As has been mentioned,

this accumulation of colloid is probably due to over-secretion of TSH from the anterior pituitary,

acting on the thyroid which is unable to produce thyroxine.

Hyperplasia

In primary Grave's disease the thyroid is uniformly enlarged and there is hyperactivity of the

acinar cells with reduplication and infolding of the epithelium. The gland is very vascular and there

is little colloid to be seen. Lymphocyte infiltration is usually a pre-dominant feature.

CLINICAL CLASSIFICATION OF THYROID SWELLINGS

The clinical assessment of a patient with an enlarged thyroid falls Into two phases.

1. First, determine the physical characteristics of the gland itself — is It smoothly enlarged,

is there a single nodule present, is it nodular?

2. Second, determine the endocrine state of the patient; euthyroid, hyperthyroid or

hypothyrold?

A synthesis of these two phases gives a simple clinical classification of the vast majority of

thyroid swellings.

The common findings are.

1. A smooth, non-toxic enlargement of the thyroid gland: this is the physiological goiter

which tends to occur at puberty and pregnancy.

2. A nodular, non-toxic gland — there being either a solitary nodule or multiple nodules.

This is the common nodular goiter.

3. A smooth toxic goiter: primary thyrotoxicosis or Graves' disease.

4. A nodular toxic enlargement: secondary thyrotoxicosis.

The less common findings are.

5. A smooth, firm enlargement (although sometimes asymmetrical and irregular) with

myxoedema, usually in a middle-aged female: Hashimoto's disease.

6. An invasive enlargement: carcinoma.

7. Riedel's thyroiditis and acute thyroidltis are uncommon.

Clinical features

Patients may present complaining of a lump in the neck and/or with symptoms due to

excessive or diminished amounts of circulating thyroxine.

The thyroid swelling

17

The characteristics of an enlarged thyroid are a mass in the neck on one or both sides of the

trachea, which moves on swallowing, since it is attached to the larynx by the pre-tracheal fascia.

The draining lymph nodes, lying in the anterior triangle of the neck, are palpated.

Evidence of retrosternal enlargement of the thyroid should be sought by percussion over the

sternum. A retrosternal thyroid can block the venous return to the superior vena cava and result in

engorgement of the jugular veins and their tributarles and in edema of the upper part of the body —

a cause of the superior mediastinal syndrome. In such cases X-rays of the thoracic inlet should be

taken; the enlarged thyroid will be stown as a radio-opaque mass in the retrosternal position.

The trachea should be examined to determine displacement or compression by the thyroid

enlargement; the patient should be asked to take a deep breath, when stridor may become apparent.

The vocal cords should be examined by indirect laryngoscopy, as thyroid enlargement may

result in damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerves and vocal cord paralysis. If surgery is

contemplated it Is obviously important to know whether or not the cords are functioning normally

before operation.

Symptoms and signs of hyperthyroidism.

Patients with hyperthyroidism (thyrotoxicosis) are usually female.

Clinical features are conveniently grouped into systems from above downwards:

1. CNS: the patient is irritable, nervous and demonstrates tremor of the outstretched fingers,

she cannot keep still.

2. The skin: is moist and hot, the patient prefers winter to summer.

3. The eyes: exophthalmos in 85 per cent.

4. The thyroid: this is usually enlarged but not invariably so; it may be highly vascular and

demonstrates a bruit and thrill.

5. CVS: a rapid pulse is almost Invariable and typically the sleeping pulse is also raised.

There may be atrial fibrillation and indeed the patient may present with heart failure.

6. Alimentary system: the patient's appetite is increased and yet she loses weight. Diarrhoea

is occasionally a feature.

Exophthalmos is present in 85 per cent of patients with primary thyrotoxicosis. The

extraocular muscles undergo lymphocyte infiltration and are swollen by edema. It appears to be

Immunologically mediated, with the extra-ocular muscles as the main target, but no antibody has

been identified to date.

The eyes have a staring appearance and when the patient is asked to follow the examiner's

finger from above the head to below it, the whites of the eyes have a staring appearance and when

the patient is asked to follow the examiner finger from above the head to below it, the whites of the

eyes will be visible above the pupils ('lid-lag'). If there is doubt, then the degree of protrusion of the

eyes can be measured by an ophthalmologist. In extremely severe exophthalmos the extrinsic

muscles of the eye may be damaged, resulting in incoordlnation of eye muscul (exophthalmic

ophthalmoplegia).

The exophthalmos is an extremely distressing condition for the patient, and, if severe, the

patient is unable to close her eyelids; the eyes are then liable to corneal ulceratlon and eventual

blindness. This condition is difficult to treat. Severe cases may respond to high dosage

corticosteroids but may require surgical decompression of the orbit and also suture of the eyelids

across the eyeball – rarsorraphy.

A rare clinical feature of hyperthyroidism is thickening of the subcutaneous tissues in front

of the tibia, the so-called 'pretibial myxoedema'.

From the clinical aspect, patients with thyrotoxicosis fall into two groups primary and

secondary (Table 1).

1. Primary thyrotoxicosis (Graves' disease) occurs usually in young women with no

preceding history of goiter. The gland is smoothly enlarged and exophtalmos is a common feature.

Symptoms are primarily those of CNS disturbance, perhaps because the young and healthy are little

disturbed by the high pulse rate.

18

2. Secondary thyrotoxicosis is a disease of middle-age, occurring In patients with a preexisting non-toxic goiter. The gland is nodular and there are no eye changes.

Table 1.

Primary and secondary toxic goiters compared.

AgePre-existing goiter

Thyroid

Exophtalmos

CNS features

CVS features

Primary

Young

Smooth

+

+++

+

Secondary

Middle aged

+

nodular

+

+++

Symptoms fall more on the CVS than on the nervous system, the patient often presenting in

heart failure with atrial fibrillation, although nervousness. Irritability and tremor may also be

present.

It is now considered that primary thyrotoxicosis is due to the action of long-acting thyroid

stimulator (LATS), a gamma-globulin produced by lymphocytes and probably an antibody to some

thyroid antigen. TSH-receptor antibodies can be demonstrated in most patients with this condition.

Secondary thyrotoxicosis is overactivity developing in an already diseased and hyperplastic gland.

Hypothyreoidism

Congenital hypothyroidism or cretinism is a condition in which the child is born with little

or no functioning thyroid. He is stunted and mentally defective, with puffy lips, a large tongue and

protuberant abdomen, often surmounted by an umbilical hernia.

In adults hypothyroidism or myxoedema usually affects women, and most often occurs in

the middle-aged or elderly. These patients have a slow, deep voice and are usually overweight and

apathetic, with a dry, coarse skin and thin hair, especially in the lateral third of the eyebrows. In

contrast with hyperthyroidism, myxedematous patients usualiy feel cold in hot weather, have a

bradycardia and are constipated. They are often anaemic and may suffer from heart failure due to

myxoedematous infiltration of the heart.

Investigations in thyroid disease.

The simplest and most reliable clinical test of hyperthyroidism is the sleeping pulse rate: the

greatest difficulty in the clinical diagnosis of hyperthyroidism is its differentiation from an acute

anxiety state. However, such patients when sleeping will have a normal pulse rate, whereas in

patients with hyperthyroidism the sleeping pulse will remain elevated.

Laboratory Investigations

I. The serum thyroxine (T4) and tri-iodothyronine (T3) can be estimated directly. Their

elevation are valuable test for hyperthyroidism.

2. Radlo-iodine studies of the thyroid gland provide very useful Information. A small tracer

dose of gamma ray emitting I131 is injected intravenously; the rate at which it is cleared from the

blood stream is a measure of thyroid activity. The gland itself can be scanned with a gamma ray

detector and areas of high activity mapped out. For instance, a nodule in the thyroid gland which is

hyperactive can be pinpointed by this method, a so-called 'hot nodule'. Similarly, a nodule that is

not producing thyroxine will not take up the radio-iodine, for example a cyst or tumour.

3. The serum cholesterol is usually raised in myxoedema and may be normal or a little low

in hyperthyroidism.

4. The basal metabolic rate is quite a useful assessment of thyroid function, provided it is

done by a reliable method and the patient is under really basal conditions; because of these

19

difficulties it is now rarely used in clinical practice. Increase in the basal metabolic rate occurs in

hyperthyroidism and the revers in myxoedema.

5. An ECG in myxoedematous cardiac involvement will show low electrical activity with

small complexes. Atrial fibrillation complicating hyperthyroidism will be confirmed.

6. Thyroid antibodies; these are detected in Hashimoto's (autoimmune thyroiditis).

7. Ultrasound gives valuable information as to whether the mass is solid or cystic.

8. Fine needle aspiration allows material to be obtained for cytological examenation.

OUTLINE OF TREATMENT OF GOITER

Non-toxic nodular enlargement

Thyroidectomy is advised in patients with an enlarged, non-toxic, nodular goiter, when there

are symptoms of tracheal compression. In addition, in younger patients, it is reasonable to advise

operation because of the danger of haemorrhage into a thyroid cyst with acute tracheal compression,

and because of the small risks of toxic or malignant change in the gland. The patient may be

concerned with the cosmetic appearance of her swollen neck, which is a perfectly valid indication

for surgery.

In elderly patients with a long-standing goiter which is symptomles it is good practice to

leave well alone.

In the patient with a single nodule in the thyroid this may be a solitary benign adenoma, a

malignant tumor, or most likely of all, a cyst in a thyroid showing histological changes of a nodular

goiter.

Just as every solitary lump in a woman's breast is best removed, it is similarly wise to advise

removal of any solitary thyroid nodule.

Hyperthyroidism

The available therapy in thyrotoxicosis comprises.

1. Anti-thyroid drugs, of which mercazolilum is the drug of choice.

2. Beta-adrenergic blocking drugs.

3. Anti-thyroid drugs combined with subsequent thyroidectomy.

4. Radio-active iodine.

Mercazolilum

This is given in a dosage of 10 mg tds and is combined with sedation and bed rest in the

acute phase of hyperthyroidism. There is rapid regression of toxic symptoms, the patient beginning

to feel better and to gain weight with reduction of tachycardia within a week or two. Unfortunately,

a high relapse rate occurs after ending treatment, even if this is prolonged for two or more years.

Medical treatment alone is therefore usually confined to the treatment of primary hyperthyroidism

in children and adolescents.

The toxic effect are drug rash, fever, arthropathy, lymphadenopathy and agranulocytosis; the

last Is the dangerous complication which is potentially lethal, but occurs in well under 1 per cent of

patients. The first symptom is a sore throat and patients on mercazolilum must be warned to

discontinue treatment immediately if this occurs and to report to hospital. Antibiotic therapy is

commenced, fresh blood transfusion given if necessary and the patient barrier-nursed until the bone

marrow recovers.

Beta-adrenergic blocking drugs

In patients with severe hyperthyroidism propranolol induces rapid symptomatic

improvement of the cardiovascular features while the hyperthyroidism comes under control with

specific anti-thyroid therapy.

Drugs And surgery combined

The majority of adult patients in this country are treated by preliminary mercazolilum until

euthyrold and are then submitted to subtotal thyroidectomy.

20

Radioactive Iodine

From the patient's point of view this is the most pleasant treatment since all she has to do is

swallow a glass of water containing the radio-iodine. There is no need for prolonged treatment with

drugs nor the risk of operation; it is particularly useful in recurrence of hyperthyroidism after

thyroidectomy. It usually takes 2 or 3 months before the patient is rendered euthyroid. Antithyrold

drugs, with or without a beta-blocker, may be used to control symptoms during this time.

There is a theoretical risk of malignant change in the irradiated gland although there has

been no report of this occurring in humans. It is, however, current practice not to use radio-iodine in

patients under the age 45 and, in addition, not to employ it in young women who may become

pregnant during treatment, since there is a very real danger of affecting the Infant's thyroid. Another

disadvantage of this treatment is the production of a high incidence of late myxoedema which rises

to near 30 per cent after 10 years and which requires replacement therapy with thyroxine.

IMPLICATIONS OF THYROIDECTOMY

In addition to the hazards of any surgical operation there are special complications to

consider following thyroidectomy. These can be divided into hormonal disturbances (the thyroid

itself and the adjacent parathyroid glands) and injury to closely related anatomical structures.

1. Hormonal.

a) tetany (parathyroid removal or bruising)

b) thyroid crisis

c) myxoedema (due to extensive removal of thyroid tissue)

d) late recurrence of hyperthyroidism (inadequate operation in the toxic gland)

2. Damage to related anatomical structures.

a) recurrent laryngeal nerve

b) injury to trachea

c) pneumothorax

3 The complications of any operation

Especially.

a) haemorrhage

b) sepsis

c) post-operative chest infection

Some of these complications require further consideration here.

Hypoparathyroidism

May result from inadvertent removal of the parathyroids or their injury during operation.

The patient may develop tetany a few days post-operationely with typical carpo-pedal spasms,

which may be induced by tourniquet around the arm (Trousseau's sign), and a positive Chvostek's

sign; this is elicited by tapittt lightly over the zygoma when the facial muscles will be seen to

contract. It serum calcium falls to below 1.5 mmol/1 (6 mg per cent).

Treatment

Consists of giving 10 ml of 20 per cent calcium gluconate intravenously followed by oral

calcium lactate 15 g daily, together with dihydrotachysterol. Often the tetany is transient and the

injured parathyroids recover; in other cases permanent treatment is required. Parathormone is not

used because the patient quicly acquires resistance to it.

In addition to frank tetany, which occurs in about 1 per cent of cases, milder degrees of

hypoparathyroldism may occur and may present with mental changes (depression or anxiety

neurosis), skin rashes and bilateral cataracts. A low post-operative calcium is treated by the

administration of calcium lactate 15 g daily by mouth.

21

Thyroid crisis

An acute exacerbation of thyrotoxicosis seen immediately post-operatlvely is now extremely

rare because of the careful pre-operatlve preparation of these patients. It is however, a frightening

phenomenon with mania, hyperpyrexia and marked tachycardia which may lead to death from heart

failure. The cause is not fully understood, but it may be due to a massive release of thyroxine from

the hyperactive gland during the operation.

Treatment

Comprises heavy sedation with barbiturates, propranolol, intravenous iodine and cooling by

means of ice packs.

Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury

The recurrent laryngeal nerve lies in the groove between the oesophagus and trachea in close

relationship to the inferior thyroid artery. Here it is at risk of division, injury from stretching, or

compression by edema or blood clot.

If one nerve alone is damaged the patient may have little in the way of symptoms apart from

slight hoarseness because the opposite vocal cord compensates by passing across the midllne during

phonation. However, if both recurrent nerves are damaged there is almost complete loss of voice

and serious narrowing of the airway; a permanent tracheostomy may be required, although an

incomplete injury may recover in time. It is estimated that the nerve is injured in about 2 to 3 per

cent of thryroidectomies.

Hemorrhage

This occurring shortly after thyroidectomy is a dangerous condition as bleeding into the

thyroid bed may compress the trachea already softened by pressure from the thyroid swelling. The

neck becomes distended with blood; there is acute dyspnoea and stridor, as well as shock from

blood loss.

Treatment

This may be an extreme emergency and must be dealt with at once by decompressing the

neck in the ward. The skin and the subcutaneous sutures are removed, the wound is opened and the

blood clot expressed. The patient can then be transferred to theatre, anaesthetized, and bleeding

points secured and the wound resutured.

THIYROID TUMOURS

Classification

Benign

Adenoma

Malignant

1. Primary.

a) adenocarcinoma (papillary of follicular)

b) anaplastic

c) medullary carcinoma (arises from the parafollicular cells, secretes calcltonin)

d) lymphoma (rare)

2. Secondary.

a) invasion from adjacent structures, e.g. oesophagus

b) very rare site for blood-bome deposits

BENIGN ADENOMA

Although benign encapsulated nodules in the thyroid gland are common, the majority are

part of a nodular colloid goiter. A small percentage represent true benign adenomas.

22

THYROID CARCINOMA

Pathology

Affect females twice as often as males, often arise in pre-existing goiters and have been

reported following radiation of the neck in childhood. There are two main groups.

1. The well-differentiated adenocarcinomas (papillary, follicular and medullary).

2. Anaplastic spheroidal cell carcinoma.

Such important differences occur between these two groups that they might almost be

considered separate disease entities.

The well-differentiated tumours comprise.

1. Papillary: the commonest type of thyroid cancer. It occurs in young adult adolescents or

even children. It is a slow-growing tumour and lymphatic spread occurs late. Deposits in the

regional lymph nodes may be solitary and in the past have been mistakenly regarded as lateral

aberrant thyroid tissue. However, a careful search of the thyroid gland will reveal a well

differentiated tumour in the homolateral lobe.

2. Follicular; occurs in young and middle-aged adults. It has a greater tendency to blood

stream spread and therefore a worsened prognosis.

3. Medullary; arises from the parafolllcular C cells and may secrete calcitonin. It may occur

at any age and, unlike other thyroid tumours, has a roughly equal sex distribution. It may be familial

and may be associated with phaeochromocvtoma and with adenomas in other endocrine glands. The

characteristic finding is deposits of amyloid between the nests of tumour cells.

The anaplastic carcinomas occur in the elderly; there is thus a reversal usual state of affairs

in that the more malignant tumours of the thyroid occur In the older age group. Rapid local spread

takes place with compression and invasion of the trachea; there is early dissemination to the

regional lymphatics and blood stream spread to the lungs, skeleton and brain.

Treatment

The well-differentiated carcinoma presenting with a localized mass in the thyroid should be

treated, after histological confirmation of the diagnosis, by total removal of the affected lobe of the

thyroid together with block dissection of the lymph nodes if these are involved.

Many of these well-differentiated tumours take up radioactive iodine and it is possible to

treat recurrences or metastases by I131 therapy. A tracer dose of radioactive iodine will give

evidence of the suitability of isotope therapy by confirming uptake of the radio-iodine in the

secondary deposits.

The anaplastic carcinomas may be treated by radical thyroidectomv but frequently these

patients present with an already inoperable mass in the neck. Palliative radiotherapy may give

temporary relief and tracheostomy may be required for the obstructed airway.

The thyroid cells are under the control of the anterior pituitary and this applies even to the

well-differentiated tumours. It has been shown that giving thyroxine will suppress the thyrotrophic

hormone of the pituitary and there have been remarkable examples of regression of well

differentiated thyroid cancer when large doses of thyroxine have been given.

Prognosis

This is very different in the two groups of cases; the well-differentiated tumours are often

associated with long survival, even in the presence of lymph node deposits, whereas patients with

anaplastic tumours are usually dead within a year or two either from local invasion or widespread

dissemination.

HASHIMOTO'S DISEASE

This is an uncommon thyroid disease which has received considerable attention since it was

the first of the auto-immune diseases to be elucidated. The patient is usually a middle-aged female

23

with clinical evidence of hypothyroidism. The gland is uniformly enlarged and firm, although it

may occasionally be asymmetrical and irregular. Its cut surface is lobulated and greyish yellow.

Histologically there is diffuse infiltration with lymphocytes, Increased fibrous tissue and

diminished colloid. It is considered to be an autoimmune disease in which the patient has developed

circulating antibodies to her own thyroid. Such antibodies, which react against thyroglobulin, can be

demonstrated in about 90 per cent of cases (reaction of Boyden).

It is important to diagnose the condition correctly by demonstrating the presence of thyroid

antibodies and, if necessary, by biopsy since thyroldectomy will precipitate severe hypothyroidism

in the cases.

Treatment

Thyroxine 0.3 mg is given daily; on this regime the gland shrinks and symptoms of

myxoedema disappear.

RIEDEL'S THYROIDITIS

An extremely rare disease of the thyroid in which the gland may be only slightly enlarged

but is woody hard with infiltration of adjacent tissues. The cause of this condition is not known, but

it may represent a late stage of Hashimoto's disease or possibly be inflammatory in origin.

It is mistaken clinically for a thyroid carcinoma, but histologically the gland is replaced by

fibrous tissue containing chronic inflammatory cells.

A wedge resection of a portion of the gland may be required if symptoms of tracheal

compression develop.