Global Citizenship and Technology: A Case Study from

advertisement

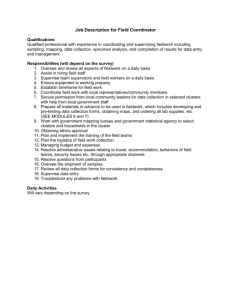

Mobile Mapping in Urban Environments Elizabeth Langran School of Education & Human Services Marymount University USA elangran@marymount.edu Abstract: This research examines the process of a high school teacher and his students as they integrated mobile technologies (phones, tablets, digital cameras, iPod touches) to capture images and data and post them to a map-based website (crowdmap.com) as an assignment for the first time. As part of their International Baccalaureate fieldwork project, the high school students are required to do actual observations in the field and write up an analytical paper. This year, the high school teacher assigned this student project using mobile devices. The resulting raw data (such as images, notes, and counting of items) were uploaded by students directly to an online class map at crowdmap.com. The researcher examined in what ways the use of the mobile devices and online mapping shaped the students' learning experience, and how the teacher perceived this assignment to be different from previous iterations completed without mobile technologies Engaging Students in Place-based Learning with New Technologies Cities have the potential to be an authentic instructional environment, but the complexity that makes these urban areas rich for learning creates challenges for educators who must ensure that students master specific learning outcomes. In experiential learning environments, the structure of assignments is critical to achieving student success, particularly when the learning is inquiry-driven. While a great deal is written about the potential of experiential learning, the results are often hit or miss. For students, translating from experience to conceptual understanding without scaffolded instructional support can be a long journey full of distractions, wrong turns and dead ends. Place-based learning, specifically mapping strategies that take advantage of mobile devices such as smart phones and tablets, is one approach that can support experiential learning experiences (Dewitt & Langran, 2012). City as Text and Moblie Learning When students leave the quiet confines of a classroom for experiential learning assignments, they must deal with sensory overload and multiple distractions, and become efficient time managers who are focused and task-oriented. In these learning environments, the structure of assignments is critical to ensuring student success, particularly when that learning is inquiry-driven. Using new technologies such as mobile devices can offer exciting learning opportunities, but also requires new pedagogical approaches that ensure that students formulate a conceptual framework for anchoring their community explorations. In higher education, City as Text is one of the leading pedagogical initiatives to take advantage of place-based learning. Developed by Dr. Bernice Braid (2000) and shared through workshops held by the National Collegiate Honors Council, this technique involves the recursive process of mapping, observing, listening and reflecting (Machonis, 2008). Resulting excursions involve an extensive planning process, which includes identifying a location and theme, selecting background materials (texts), and creating several participant assignments. The goal for City as Text participants is to hone their observational skills and generate questions that require additional information. The City as a Text model differs from just exploring the city. While analyzing a city “as text” is more likely to produce deep learning, it also requires a significant time investment on the part of those creating the experiences as well as participating in the experiences. More recently, Blair (2011) refines the idea of place-based learning by incorporating urban mapping as an experiential learning pedagogy in study abroad programs. Like City as Text, his approach requires that students use observation skills to create maps that are annotated with personal photography, thereby anchoring their conceptual understanding that was gained from course readings in the authentic context of urban neighborhoods. Recognizing the importance of developing a conceptual map to frame their experiences, he creates directed excursions that guide students through the streets of Paris, increasing the likelihood that they will successfully master the targeted course outcomes. Students complete this series of excursions, which were created to focus on particular aspects of the social and urban fabric of Paris (Dewitt & Langran, 2012). In the realm of K-12 education, there are emerging methods of place-based learning designed to engage students in mobile learning, such as WonderPoints (developed by Dr. Bernie Dodge, SDSU faculty and creator of WebQuests), and History Pin (developed by international group We Are What We Do, in partnership with Google). In each of these methods, mobile devices are used to stimulate learning by having students craft their own inquiry-based experience. The place-based learning then gets integrated back into the classroom, where the instructor guides student discussions to model the process of analysis. Bernie Dodge refers to this as mgagement—engagement fostered by mobile learning (Dodge, 2011). In the Wonderpoints learning structure, students identify a location of interest, and while on location, capture voice notes and photos that are geotagged. Students propose questions, rate them for “interestingness,” and then conduct research to find the answers. As in an inquiry-based model, students can engage in the wonder of asking questions and discovering answers. History Pin also tags or “pins” images to a specific geographical location, but rather than the student-created present-day photos of WonderPoints, History Pin uses images and stories from the past. These images and stories are then uploaded to the History Pin community website and can be accessed on-location using the free mobile application. The resulting interaction allows students to imagine change over time—how a location looked during a different historical period—and learn about the associated stories. … the concept of learning immediately conjures up images of classrooms... Yet in our experience, learning is an integral part of our everyday lives. …part of our participation in our communities... The problem is not that we do not know this, but rather we do not have very systematic ways of talking about this familiar experience (Wenger 2009, p. 214). As Wenger notes, the problem for educators is developing systematic ways to explore familiar territory. Mapping strategies with hand-held devices have the potential to be an effective way of enabling students to move fluidly between concrete experience and the process of conceptualization (Dewitt & Langran, 2012). Transforming a High School Assignment This research focuses on one Geography teacher and his high school students from the close suburbs of a mid-Atlantic city. As part of their International Baccalaureate (IB) fieldwork project, which is specified in the IB Geography curriculum, students are required to (a) do actual observations in the field; and (b) write up an analytical paper of 1,500 words, describing their research question, hypothesis, data collection methods, data analysis, and conclusions. The fieldwork topic is related to one of the major course themes, “urban environments.” The written analytical paper is required to be individual, but the fieldwork is explicitly allowed to be a group project, which in the past has made it possible to undertake projects involving students pooling data from many sites in the local region, and allowing everyone to draw as needed on the pooled data. To provide relevant data for analysis, the IB wants students, if possible, to conduct observations and measurements that can be subject to simple statistical analysis. In the past, fieldwork topics have tried to meet these requirements by, for example, mapping the distribution of one particular type of restaurant and comparing that to the distribution of some other type of restaurant or fast food chain, noting differences in distribution patterns, and attempting to determine the factors that may have led to such geographic differences. Most work in the past has been done with simple paper and pencil charts and clipboards, supplemented by photographs and, back at home, Google map searches of the full lists of certain types of facilities. This year the IB classroom teacher proposed a comparison of the geography of (#1) a segment of a highly developed corridor with (#2) a very much more suburban commercial strip. One of the primary objectives of the IB Geography curriculum is to understand changes and development in land use patterns, for which these two areas provide sharply different examples of ways of organizing space and activities. To do this, students worked in small groups of four or five students each, to (a) identify, count, categorize, and map facilities, e.g. grocery stores, restaurants, and other retail outlets, non-commercial spaces, and residential units; (b) describe the physical layout, e.g. number of stories of buildings, (and uses of upper stories), parking arrangements (most of area #2 is open asphalt, whereas there is limited on-street parking in area #1, plus garages; (c) count both vehicle and foot traffic in the assigned area; (d) count customers at an assigned retail facility in that area. This type of fieldwork data collection was done using mobile devices, including cellphones, tablets, digital cameras, and iPod Touches. The resulting raw data (such as images, notes, and counting of items) were uploaded directly to a password protected on-line class map at crowdmap.com. The researcher examined in what ways the use of the mobile devices and online mapping shaped the students' learning experience, and how the teacher perceived this assignment to be different from previous iterations completed without mobile technologies. The research also focused on the following questions: Technology: Are the mobile devices and applications functional and easy to use? Does the protocol work on multiple platforms? Do students have sufficient access to technology devices to conduct their own place-based learning experiences? Replicability/sustainability: Are the procedures clear enough for other educators to conduct their own place-based learning experiences? Can it be used across content areas? Can it be easily used in other locations or even other countries for study abroad? Are additional resources needed? Student learning: Does this project enable students to combine their understanding of course objectives with a sense of place? Is it an engaging learning experience for the students? Community connections: Does this project help create closer ties to the communities in which the students are collecting data? Methodology Participants and Instruments One high school teacher and his IB Geography students (n=75) participated in this study. This teacher was selected for this study because he approached the researcher with an interest to try out this new method of teaching his students, and thus represents a convenience sample. The teacher delivered the instruction to the students and oversaw the mobile mapping assignment; the researcher served as a technology consultant to the teacher. Because this is a relatively new area of study, this research was primarily qualitative in nature, relying on self-report from the classroom teacher and students on the efficacy and utility of this approach. The following was used to collect data and later analyzed, following the completion of the student assignment: 1 - An online survey of students; 2 - interview with the classroom teacher; and 3 - document analysis of submitted student assignments. Data and Procedures This study used primarily qualitative measures, with additional quantitative data used to achieve convergent validity and a more complete understanding of the use of mobile learning and mapping technologies among participants. The quantitative data came from a document analysis of the online assignments submitted to the crouwdsourcing.com website. The qualitative data was collected in the forms of participant surveys from students and an interview with the classroom teacher. The interview, survey, and document analysis were coded based on emergent themes. Data were reduced to that which applies to each code. Analytic memos were written as a place where the researcher put thoughts and hunches about how to make sense of the data. Patterns and themes were noted among the data from different sources. The quantitative items (some survey items; student assignments) used descriptive statistics. Analytic induction was employed to test hypotheses produced from the data by asking follow-up questions with the classroom teacher at the completion of the initiative, and reformulating hypotheses as necessary. Following the model suggested by Huberman and Miles (1994), data were reduced through coding and reporting, and displayed in narrative form. The study is limited by the absence of a control group for comparison; by the limited size of the study; and by the inclusion of only one classroom teacher. Results In total, 158 reports from the students’ fieldwork data collection appeared on the online map. Each report contained a photo, a location that appeared on a common map, and a category (grocery, restaurant/café, fast food, other). Most of the reports included a description of the site, but varied in level of detail. The information generally included in the text accompanying each report stated the names of the group members, a brief description of the site and types of people present, numbers of people by race observed during the time period, and count of high-end, mid-range, and low-end cars in the parking lot, if applicable. The Student Experience The student survey revealed that 78% of respondents (n=27) found the Ushahidi Crowdmap app functional and easy to use. A couple of students had trouble with the app crashing, and two voiced the wish to more easily go back and edit reports directly from inside the app after submission (this can be done more easily on the website). Twenty students used iPhones, four used Android phones, and three used iPod Touch devices. When asked about the use of the technology as part of the assignment, most (52%) found it easy to collect and share the data, and found it to be a fun learning experience. Table 1: Survey of students about the assignment (n=27) Did the Crowdmap Site and your mobile device… make it easy to collect data? make it easy to share data? make it a fun learning experience? Yes A little bit No 14 7 6 14 7 6 14 10 3 While three students experienced technological barriers due to an app crashing or not functioning properly, several student comments indicated that the integration of the technology added value to the assignment: Uploading the pictures was easy and it was also fun to see photos of the places other groups visited. Collecting data was done with ease and worked better than the traditional paper and pencil technique. The assignment was unique and interesting. Before the assignment, I have never been to Clarendon Boulevard and had no idea that it even existed. Afterwards, I am open to an entire new world beyond Annandale that I now explore frequently. For that I thank you. One of the goals of this type of assignment is to increase ties to the local community in which the students collected data. The above comment, for example, demonstrates a change in this student’s community connection. Of the 27 respondents, only three indicated that this assignment did not help them feel more closely tied to the community in which they collected the data. The Teacher Experience The classroom teacher indicated that he intends on using mobile technologies in this assignment again, based on the experience that 1. The technology was easy for students and the teacher. 2. The visual nature of the assignment allowed students to extend their learning. 3. The students can use the data flexibly. 4. It was fun for the students. The Ushahidi/Crowdmap website and app was developed to report incidents of crime, fires, election violations, etc.; nevertheless, the teacher did not find it difficult to repurpose the website to suit the needs of the assignment, and commented, “I think the students found it easy.” Aside from a handful of students whose applications crashed on their phones, no technology issues were reported by the teacher or students. In previous years, the teacher provided the students with a checklist for the fieldwork, and some students chose to take photographs as well. While many of the questions the students were choosing to explore this year were similar to many the students used in the past, the teacher did note a few differences. One distinction was that students were taking photos from inside the restaurants and other establishments, and were taking many more photos than ever before, prompting them to “extend what you’re looking at.” The teacher observed that the visual nature of the activity allowed students to “see where the clusters of activity are.” For example, one student conducted a nearest neighbor analysis on white majority restaurants; the teacher noted that “that comes from looking at the clusters.” As the students began to think about how to write their paper up, the teacher felt they could use the data they posted online flexibly, integrating maps and photos into the paper as an illustration of what they were positing in their paper. One student for example was comparing the two neighborhoods he explored doing a ratio of how many people were walking on the street to how many cars driving on the street, which was quite different in both neighborhoods. The teacher pointed out how the student can use the photos and maps to illustrate this distinction in his paper. The classroom teacher expressed his intention to repeat doing this assignment next year with the same technology because he believes the students found it fun: I would do it again simply as an adjunct to making it more fun. I don’t think it’s necessary. But I think it makes it more fun and it may open their eyes a bit more, pay attention to more stuff...It helps make the project more exciting. While the technology is not essential to this project (it was done without technology for several years), the teacher found that the technology was a worthwhile addition to the assignment: “Anything you can do for high school students to make it more interesting and fun is worth doing.” Conclusion The use of mobile devices in field-based classroom assignments appears to be a useful pathway for student engagement and connections to the community in which the students are exploring. The easeof-use and fun provided by the mobile technologies in the classroom were regarded by this classroom teacher as a worthwhile endeavor. As students are coming to schools with familiarity with and access to handheld devices, it makes sense to take advantage of their possibilities both inside and outside of classroom walls. Further research will be necessary to determine the best approaches to support City as Text and other place-based learning pedagogies. References Blair, S. (2011, Spring). Study abroad and the city: Mapping urban identity. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad, 20, 37-54. Braid, B. & Long, A. (2000). Place as text: Approaches to active learning. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nchcmono/3/ Dewitt, J. & Langran, E. (2012). Exploring the world begins at home. Unpublished grant proposal, Marymount University, Arlington, VA. Dodge, B. “WonderPoints: A structure for engaging curiosity about the outdoors with mobile devices.” International Society for Technology in Education [Conference]. Philadelphia. 29 June 2011. Huberman, E. A., & Miles, M. B. (1994). Data management and analysis methods. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Machonis, P.A. (2008). Shatter the glassy stare: Implementing experiential learning in higher education A companion piece to place as text: Approaches to active learning. Lincoln, NE: National Collegiate Honors Council. Wenger, E. (2009). A social theory of learning. In K. Illeris (Ed.), Contemporary theories of learning: Learning theorists…in their own words (pp. 208-218). London: Routledge.