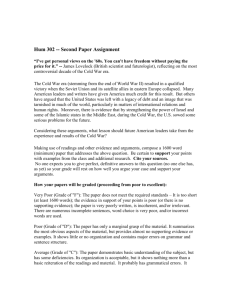

FIN 367 - Investment Management - Ritter

advertisement

FINANCE 367 INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT (UNIQUE # 03720) FALL 2014 Professor Class Class Hours Office Office Hours Phone E-Mail Course Web Page Teaching Assistant John T. Ritter TBD Tuesday and Thursday 8:00 – 9:30 6.210 GSB - Walkway Tuesday and Thursday 7:00 – 8:00 a.m. or by appointment 512-799-7749 (c) john.ritter@mccombs.utexas.edu via Canvas I prefer that you see me with questions Course Objectives This course is designed to be a survey of the field of investments. The course will focus on the application of financial theory to the issues and problems of investment management. In particular, you should leave this class understanding the components used to put together a portfolio. This requires you to understand many different types of investable assets (bonds, stocks, mutual funds, and derivatives), how they are combined to form a portfolio, and how they are each affected by the overall economy. In addition, there is background and fundamental information which is necessary to understand. This information includes topics such as types of markets, how to place orders, behavioral finance and what stock indices represent. Prerequisites Finance 367 is a Restricted Course for students who are currently enrolled in a major program in the College of Business and Administration. Note that several prerequisites apply for this course and are published in the Course Schedule. Prior completion of Finance 357 or Finance 357 H, Statistics 371G or Statistics 371 H are among these requirements. In addition, proficiency in mathematics and spreadsheet packages (Excel) is assumed. Students who are uncertain as to whether they satisfy these requirements should notify the instructor. What this Means: 1) I will not teach you how to use your financial calculator – I assume you know how to use it as it was required for FIN 357. 2) I will not cover basic Present Value, Net Present Value, or Future Value theory or concepts in class as again this was taught in FIN 357. 3) I will not cover basic statistical methodology in class such as mean, standard deviation, correlation, linear regression, covariance, etc. You have been exposed to this before and it is covered again in the text book. I know it has been a long summer and what you learned last year has remanded itself to the farthest reaches of your minds. So, if enough students request an overview of these concepts I will set up a refresher session on these topics outside of class during the first few weeks of class. Ritter FIN 367 – Fall 2014 page 2 Materials Textbook: Investments, 10h Edition by Bodie, Kane & Marcus (McGraw Hill, 2011) – available at the Co-Op Supplementary Readings & Lecture Slides: All supplementary readings listed in the syllabus and lecture slides will be available on-line on Canvas. Lecture Slides (if any) will be available following the class. Lecture Slides are meant as an outline to reduce the amount of rote copying of definitions and formulas but certainly not as a self-contained lecture summary. Reading the lecture slides without attending class will most likely be of little benefit. Additional Readings: Additional readings regarding current events may be made available as Handouts or posted on-line via Canvas. Book for Project: “The Essays of Warren Buffett: Lessons for Corporate America” by Warren Buffett and edited by Lawrence Cunningham (3rd Edition). I don’t care which version they are all about the same if you want to save money by buying a 2nd edition. You must buy this on your own – it is sold by Amazon (and others). Calculator: You will need a business calculator for this class. The calculator should have the following keys: IRR, n, i, PV, PMT, FV, and CF. As long as those keys are present, the calculator is fine. If you may consider taking the CFA exam in the future, I recommend the HP 12c (this calculator is the finance industry standard and one of only two calculators that may be used on the CFA exam). The other calculator which is permissible for the CFA exam is the Texas Instruments BA II Plus. You should bring a financial calculator to every one of our class meetings I will ask you to use it – frequently. Strongly Recommended: Bloomberg.com, WSJ, Financial Times, The Economist, or some other Financial News source Professionalism Policy The highest professional standards are expected of all members of the McCombs community. The collective class reputation and the value of the program’s experience hinges on this. Faculty are expected to be professional and prepared to deliver value for each and every class session. Students are expected to be professional in all respects. This Includes: -Being on-time and in your seat when class starts -Staying until the end of class -Being constructive to the learning environment -Being “present” in the class and focused on class material. This includes, but is not limited to no internet, no email, no cell phones, no laptops, no texting, and no talking to your neighbor about last night. -Coming prepared to contribute to the class -Communication with the professor Think about this class as though it were a job, and this is a bi-weekly meeting with a senior executive at your firm. Would you show up late, unprepared, be texting during the meeting? Of course not! Professionalism in class is a good discipline to prepare you for the real world. As the semester progresses, you will realize that I will hold you to a very high standard, but I will hold myself (and how this class is presented) to an even higher one. Ritter FIN 367 – Fall 2014 page 3 Grading Your grade in the course will be determined as follows: Mid-Term Exam (Classes 1 through 15) Final Exam (Comprehensive): Book Review of “The Essays of Warren Buffet” Weekly Problem Sets Group Project – Portfolio Management 20% 30% 15% 15% 20% Letter grades for the course will be based on the student’s ranking in the course relative to other students (i.e., the curve) as shown to the left. In general, there will be about 30% A’s, 40-50% B’s, 20-30% C’s or below. Plus/minus grades will be assigned for the final grade (there is no A+ though). With that said, grades are typically curved up substantially at the end of the semester. Curves are done for the class as a whole, not for individuals. In other words, someone with a final course grade of 88 will not get a higher grade than someone with a course grade of 89 as long as that person is eligible for the curve. Also, there will be a uniform grading average target for all 367 classes which will be somewhere between 3.2 & 3.4 which equates to roughly a B+ on the above scale. Finally, be vigilant of your final grade. If you receive a grade that does not look right, let me know. Appeals: There are no verbal appeals of grade changes. You should submit a written statement explaining the problem within one week of receiving your grade and we will be happy to re-grade any exam or assignment. The entire exam or project will be re-graded and the score may increase, remain the same, or even decrease. Late Assignments: Assignment turned in after the start of Class will lose 25% of the grade. After 1 day, an assignment will not be accepted. Bad Questions: Unfortunately, there are poorly written questions that find their way into exams from time to time. If more than 80% of the class misses a question, it will automatically be deemed a ‘bad question’ and removed from consideration. Fairness to Students: I strive to treat students with dignity and fairness. This does not mean that I will agree with your ideas or opinions. If you feel that I have been unfair in any way, please let me know. It takes courage to do so. Make-Up Work: There are no do-overs in the business world. Likewise, there are no make-ups or extracredit given in this class. Class Preparation It is particularly important to me that you prepare for class, arrive on time, stay for the entire class, keep your laptops and other non-necessary electronics closed and most of all respect your peers. Being prepared for class means that you have read the assigned materials and that you have worked any assigned problems. That way, you will have thought about the material already. I do not collect homework. The problem sets will be accessed online and will be automatically graded. I will go over most of the problems in class starting with the ones most missed by the class. Please note that the problem sets are only available until Ritter FIN 367 – Fall 2014 page 4 midnight before class. Please do not procrastinate. Once the deadline has passed, there will not be an opportunity to make up. There are 118 points out of 100 assigned, which allows you to make up for other grades with an exceptional job on the homework. It also allows you to miss a few assignments and still receive a 100. You may access this courses Connect material via the following link: http://connect.mheducation.com/class/j-ritter-fall-2014---03720 Class Participation Class participation and questions are encouraged! If you have a question, you can be assured that someone else in the class has the same question, so ask. However, participation will not always be voluntary. This is why it is important to come to class prepared. Class contribution consists of positive and constructive comments, questions, remarks, and answers in class. Effective contribution means participating such that your answer or question moves our analysis and understanding forward. In addition, as with your future employer, your participation includes participating in the class in an ethical and upstanding manner. Any violations of the honor code or inappropriate attitude in class will be met with zero tolerance, removal from the classroom, and potential prosecution under University guidelines. Attendance Policy and Late Policy I expect you to attend class and I expect you to be on time. I understand that things happen – you oversleep, a bus runs late, you’re sick, etc. When students don’t come to class tend to receive grades of D or F on the exams. When students arrive late, they are generally confused and tend to disrupt other students and the teaching of the class. I will not take attendance. However, I will cover a significant number of topics in class that are not covered in the text book. So skip class at your own risk. If you need to leave the class early for any reason, please let me know before the beginning of the class period and leave quietly so as not to disturb the other members of class. Students should attend the class section to which they are registered. I only teach 1 section. My class will cover different topics than or topics in a different order than other professors. Preparing for the Exams You need to read each chapter and do the homework problems. I will teach you material in class and then you will need to spend time working AFTER class. You will need to review what we did in class and work problems. Working problems is essential. You should read the textbook when you are having difficulty understanding my notes and problems. I have also provided a number of other background readings for areas that are of particular difficulty that can be found under Class Readings on Canvas. If you still have questions, please come see me during my office hours as soon as possible. This class utilizes a lot of non-textbook readings. These readings are used to enhance and expand on the text book readings and provide additional real world application for the discussions. You will not be tested on anything in the non-textbook readings that is not specifically discussed in class. This means you do not need to memorize all of the facts and ideas in these readings. However, you do need to read them in order to be able to actively discuss them in class. Exams The Mid-Term exam will be held online and will cover material covered up to that point in class. (Through Class #15). The midterm will be available beginning Monday October 20th and be available through midnight of the 21st. Once you start the exam, you will have 2 hours to complete it. It will be open book. However, you will not have time to look up answers and complete the exam. Further, most of the questions are algorithmic, which means the questions you receive will not be identical to others. Ritter FIN 367 – Fall 2014 page 5 The Final Exam will be comprehensive and will cover material from lectures, class discussions, assigned readings, and guest lectures. Exams will strive to test the comprehension level, not merely memorization skills. Exams tend to include most of the material that I have taught (rather than just a few big questions). The tests will include both qualitative and quantitative material. The qualitative questions are usually short answer or multiple-choice. The difficulty level of the multiple-choice questions is intended to parallel the level of question that you could face on the CFA® exam. I do not release old exams. I have found that releasing old exams is problematic because (1) it results in people studying “to the exam” rather than studying to learn; and (2) students inevitably feel that old exams are easier than the current exam. In addition, I do not allow students to keep their exams. This maintains the fairness of exams, since you know that no one has seen old exams. You will have ample opportunity to review your exam during the week following the reception of the grade. Book Review Project This project is intended to further your Investments education and to help you to realize that you can continue to educate yourself when you graduate. For your project, I want you to write a paper about “The Essays of Warren Buffett: Lessons for Corporate America” by Warren Buffett and edited by Lawrence Cunningham (3rd Edition). Your paper should be a well-written, coherent summary that addresses the following topic: “Key Takeaways from ‘The Essays of Warren Buffett’”. There are two reasons that I have you do this project: (1) people love this book; and (2) there is probably no better way to learn about the market and investing than by reading Buffett’s letters to his shareholders. This book consolidates key points from letters. If you have further interest, all of his letters are available online at www.berkshirehathaway.com. Your paper cannot be longer than five pages plus a cover page. In the business world, getting your point across succinctly and concisely is highly valued. Doing so takes time. Pascal is quoted as saying, “I would have written you a shorter letter if I only had more time.” Five pages is the total (other than the cover) regardless of whether you call something an appendix or anything else. I will stop reading at five pages. Anything after that point will not be considered. The goal of your paper should be to allow someone who has not read this book to fully understand what it is about. A good paper clearly distinguishes thoughts. Your paper should evidence that fact that you have read the entire book. The project is not a grade differentiator. The reality is that the exams will result in grade differentiation. The project is a learning exercise and the grading scale is normally pretty tight (usually 88 - 94). With that said, every so often someone turns in something that results in a significantly lower grade. The fact that the grade range is normally tight is not intended to diminish the importance of this assignment. This assignment is to be done alone. Examples of times that people receive low grades include when someone clearly has not read the entire book or turns in a paper that is full of grammatical errors. If you have not read the entire book, the highest grade you can receive is 50 (and that score isn’t likely). But, if you read the book and you feel like you have made a good-faith effort, you should not worry. You will know if you fall into one of the “troubled” categories. Group Project Details of this will be handed out separately and are posted on Canvas. FIN 367 – Fall 2014 Ritter page 6 Tentative Class Schedule All readings correspond to “Investments” 10th Edition by Bodie, Kane, & Marcus (McGraw Hill, 2012). Readings are to be read ahead of class. All classes will be held in GSB 5.142A on Tuesdays & Thursdays from 8:00 to 9:30. The following Schedule is Subject to Change. Check Canvas for any updates and the latest version. Due Dates Mid-Term Exam – October 21, 2014 Book Report Due – November 26, 2014 Group Project Due – December 5, 2014 Final Exam – Based on UT Schedule Connect Problems – Due before each class Thursday, August 28 Class#1 The Investment Environment Textbook: Chapter #1 Readings: None Video: How the Economic Machine Works by Ray Dalio – Bridgewater Associates Online Problem Set: 5 Q’s in Connect Tuesday, September 2 Class #2 Asset Classes & Financial Instruments Textbook: Chapter #2 Readings: JPM Guide to the Mkts 3Q14 AMZ Facts & Methods (2 articles) Online Problem Set: 10 Q’s in Connect Thursday, September 4 Class #3 How Securities are Traded Textbook: Chapter #3 Readings: Embracing Complexity Online Problem Set: 10 Q’s in Connect Tuesday, September 9 Class #4 (No Class) Mutual Funds & Investment Companies Textbook: Chapter 4 Readings: ETF Market Structure…. Online Problem Set: 16 Q’s on Connect Thursday, September 11 Class #5 Risk, Return & the Historical Record Textbook: Chapter 5 Readings: Understanding Expected Returns. Online Problem Set: 10 Q’s on Connect (Optional Makeup class on September 12) Tuesday, September 16 Class #6 Capital Allocation to Risk Assets Textbook: Chapter 6 + Appendices Readings: Does Asset Allocation Explain… Online Problem Set: 19 Q’s on Connect Thursday, September 18 Class #7 Optimal Risky Portfolios Textbook: Chapter 7 + Appendices Readings: None Online Problem Set: 18 Q’s on Connect Ritter FIN 367 – Fall 2014 Tuesday, September 23 Class #8 Index Models Textbook: Chapter 8 Readings: None Online Problem Set: 12 Q’s on Connect Thursday, September 25 Class #9 Capital Asset Pricing Model Textbook: Chapter 9 Readings: None Online Problem Set: 22 Q’s on Connect Tuesday, September 30 Class #10 Arbitrage Pricing Theory & Multifactor Models Textbook: Chapter 10 Readings: Factor Investing: When Alpha becomes Beta Online Problem Set: 11 Q’s on Connect Thursday, October 2 Class #11 The Efficient Market Hypothesis Textbook: Chapter 11 Readings: The Fallibility of Efficient Markets Online Problem Set: 10 Q’s on Connect Tuesday, October 7 Class #12 Behavioral Finance Textbook: Chapter 12 Readings: Demographics of Overconfidence Behavioral Sciences 101 Problems: 10 Q’s on Connect Thursday, October 9 Class #13 Empirical Evidence on Security Returns & International Diversification Textbook: Chapters 13 & 25 Readings: International Diversification Works Problems: 6 Q’s on Connect Tuesday, October 14 Class #14 Portfolio Performance Evaluation Textbook: Chapter 24 Readings: None Problems: 12 Q’s on Connect Thursday, October 16 Class #15 Investment Policy & Process Textbook: Chapter 28 Readings: Elements of an IPS Problems: 2 Q’s on Connect Tuesday, October 21 Class #16 The All Weather Portfolio – A Different Perspective Textbook: None Readings: Bridgewater All Weather Strategy Problems: None Online Midterm Exam due by 11:59 PM Thursday, October 23 Class #17 Financial Statement Analysis Textbook: Chapter 19 Readings: None Problems: 8 Q’s on Connect page 7 Ritter FIN 367 – Fall 2014 Tuesday, October 28 Class #18 Financial Statement Analysis – II & Macro & Industry Analysis Textbook: Chapter 17 Readings: None Problems: 12 Q’s on Connect Thursday, October 30 Class #19 Bond Prices & Yields Textbook: Chapter 14 Readings: None Problems: 25 Q’s on Connect Tuesday, November 4 Class #20 Term Structure of Interest Rates Textbook: Chapter 15 Readings: None Problems: 18 Q’s on Connect Thursday, November 6 Class #21 Managing a Bond Portfolio Textbook: Chapter 16 Readings: What Practitioners need to know about Duration & Convexity Problems: 18 Q’s on Connect Tuesday, November 11 Class #22 Equity Valuation Models Textbook: Chapter 18 Readings: Note on Cash flow Valuation Methods What’s it Worth Problems: 17 Q’s on Connect Thursday, November 13 Class #23 Option Markets & Trading Textbook: Chapter 20 Readings: None Problems: 10 Q’s on Connect Tuesday, November 18 Class #24 Option Valuation Textbook: Chapter 21 Readings: None Problems: 38 Q’s on Connect Thursday, November 20 Class #25 Forward and Futures Markets Textbook: Chapter 22 Readings: None Problems: 6 Q’s on Connect Tuesday, November 25 Class #26 Futures, Swaps, & Risk Management Textbook: Chapter 23 Readings: None Problems: 16 Q’s on Connect November 27, 2014 Thanksgiving Break page 8 FIN 367 – Fall 2014 Ritter Tuesday, December 2 Class #27 Ethics Textbook: None Readings: CFA Code of Ethics The Ethical Mind Problems: Buying Lubrizol – Case Study page 9 Thursday, December 4 Class #28 Theory of Active Portfolio Management Textbook: Chapters 26 & 27 Readings: Engineering Targeted Returns & Risks The Right Answer to the Wrong Question Problems: 11 Q’s on Connect THIS OUTLINE SHOULD BE CONSIDERED REPRESENTATIVE OF THE MATERIAL WE WILL COVER DURING THE SEMESTER; IT IS SUBJECT TO CHANGE UPON PROPER NOTIFICATION – WHICH INCLUDES POSTING ON CANVAS AND / OR IN CLASS NOTIFICATION. ACADEMIC DISHONESTY There is no tolerance for acts of academic dishonesty. Such acts damage the reputation of the school and the degree and demean the honest efforts of the majority of students. Any student engaging in any form of academic dishonesty will be dealt with in the most serious manner. These acts include but are not limited to: lying, cheating, stealing (e.g., answers), multiple submissions, plagiarism (including, improper attribution of sources), unauthorized cooperation, and misrepresentation of facts. Note that it is your responsibility for understanding all attributes of proper conduct. In particular, students should understand exactly how to engage in proper citations, changing sentence structure around is still paraphrasing. If ideas are borrowed from someone and phrased in your own wording, citation is always required. Lack of knowledge is no excuse. Please carefully read: http://deanofstudents.utexas.edu/sjs/scholdis_plagiarism.php and http://www.yale.edu/bass/writing/sources/plagiarism/what.html. The responsibilities for both students and faculty with regard to the Honor System are described on http://mba.mccombs.utexas.edu/students/academics/honor/index.asp and http://deanofstudents.utexas.edu/sjs/acint_student.php. As the instructor for this course, I agree to observe all the faculty responsibilities described therein. If the application of the Honor System to this class and its assignments is unclear in any way, it is your responsibility to ask me for clarification. Any individual assignment should be completed individually without help from others. Group preparation for examinations is acceptable and encouraged. STUDENTS WITH DISABILITIES Upon request, the University of Texas at Austin provides appropriate academic accommodations for qualified students with disabilities. Services for Students with Disabilities (SSD) is housed in the Office of the Dean of Students, located on the fourth floor of the Student Services Building. Information on how to register, downloadable forms, including guidelines for documentation, accommodation request letters, and releases of information are available online at http://deanofstudents.utexas.edu/ssd/index.php. Please do not hesitate to contact SSD at (512) 4716259, VP: (512) 232-2937 or via e-mail if you have any questions. FIN 367 – Fall 2014 Ritter page 10 Appendix: Excerpts Directly from the University of Texas at Austin Office of the Dean of Students website (http://deanofstudents.utexas.edu/sjs/acint_student.php) “The Standard of Academic Integrity A fundamental principle for any educational institution, academic integrity is highly valued and seriously regarded at The University of Texas at Austin, as emphasized in the standards of conduct. More specifically, you and other students are expected to "maintain absolute integrity and a high standard of individual honor in scholastic work" undertaken at the University (Sec. 11801, Institutional Rules on Student Services and Activities). This is a very basic expectation that is further reinforced by the University's Honor Code. At a minimum, you should complete any assignments, exams, and other scholastic endeavors with the utmost honesty, which requires you to: acknowledge the contributions of other sources to your scholastic efforts; complete your assignments independently unless expressly authorized to seek or obtain assistance in preparing them; follow instructions for assignments and exams, and observe the standards of your academic discipline; and avoid engaging in any form of academic dishonesty on behalf of yourself or another student. For the official policies on academic integrity and scholastic dishonesty, please refer to Chapter 11 of the Institutional Rules on Student Services and Activities. What is Scholastic Dishonesty? In promoting a high standard of academic integrity, the University broadly defines scholastic dishonesty—basically, all conduct that violates this standard, including any act designed to give an unfair or undeserved academic advantage, such as: Cheating Plagiarism Unauthorized Collaboration Collusion Falsifying Academic Records Misrepresenting Facts (e.g., providing false information to postpone an exam, obtain an extended deadline for an assignment, or even gain an unearned financial benefit) Any other acts (or attempted acts) that violate the basic standard of academic integrity (e.g., multiple submissions— submitting essentially the same written assignment for two courses without authorization to do so) Several types of scholastic dishonesty—unauthorized collaboration, plagiarism, and multiple submissions—are discussed in more detail on this Web site to correct common misperceptions about these particular offenses and suggest ways to avoid committing them. For the University's official definition of scholastic dishonesty, see Section 11-802, Institutional Rules on Student Services and Activities. Unauthorized Collaboration If you work with another person on an assignment for credit without the instructor's permission to do so, you are engaging in unauthorized collaboration. This common form of academic dishonesty can occur with all types of scholastic work—papers, homework, tests (takehome or in-class), lab reports, computer programming projects, or any other assignments to be submitted for credit. For the University's official definitions of unauthorized collaboration and the related offense of collusion, see Sections 11-802(c)(6) & 11-802(e), Institutional Rules on Student Services and Activities. Some students mistakenly assume that they can work together on an assignment as long as the instructor has not expressly prohibited collaborative efforts. Actually, students are expected to complete assignments independently unless the course instructor indicates otherwise. So working together on assignments is not permitted unless the instructor specifically approves of any such collaboration. FIN 367 – Fall 2014 Ritter page 11 Unfortunately, students who engage in unauthorized collaboration tend to justify doing so through various rationalizations. For example, some argue that they contributed to the work, and others maintain that working together on an assignment "helped them learn better." The instructor—not the student—determines the purpose of a particular assignment and the acceptable method for completing it. Unless working together on an assignment has been specifically authorized, always assume it is not allowed. Many educators do value group assignments and other collaborative efforts, recognizing their potential for developing and enhancing specific learning skills. And course requirements in some classes do consist primarily of group assignments. But the expectation of individual work is the prevailing norm in many classes, consistent with the presumption of original work that remains a fundamental tenet of scholarship in the American educational system. Some students incorrectly assume that the degree of any permissible collaboration is basically the same for all classes. The extent of any permissible collaboration can vary widely from one class to the next, even from one project to the next within the same class. Be sure to distinguish between collaboration that is authorized for a particular assignment and unauthorized collaboration that is undertaken for the sake of expedience or convenience to benefit you and/or another student. By failing to make this key distinction, you are much more likely to engage in unauthorized collaboration. To avoid any such outcome, always seek clarification from the instructor. Unauthorized collaboration can also occur in conjunction with group projects. How so? If the degree or type of collaboration exceeds the parameters expressly approved by the instructor. An instructor may allow (or even expect) students to work together on one stage of a group project but require independent work on other phases. Any such distinctions should be strictly observed. Providing another student unauthorized assistance on an assignment is also a violation, even without the prospect of benefiting yourself. If an instructor did not authorize students to work together on a particular assignment and you help a student complete that assignment, you are providing unauthorized assistance and, in effect, facilitating an act of academic dishonesty. Equally important, you can be held accountable for doing so. For similar reasons, you should not allow another student access to your drafted or completed assignments unless the instructor has permitted those materials to be shared in that manner. Plagiarism Plagiarism is another serious violation of academic integrity. In simplest terms, this occurs if you represent as your own work any material that was obtained from another source, regardless how or where you acquired it. Plagiarism can occur with all types of media—scholarly or non-academic, published or unpublished—written publications, Internet sources, oral presentations, illustrations, computer code, scientific data or analyses, music, art, and other forms of expression. (See Section 11-802(d) of the Institutional Rules on Student Services and Activities for the University's official definition of plagiarism.) Borrowed material from written works can include entire papers, one or more paragraphs, single phrases, or any other excerpts from a variety of sources such as books, journal articles, magazines, downloaded Internet documents, purchased papers from commercial writing services, papers obtained from other students (including homework assignments), etc. As a general rule, the use of any borrowed material results in plagiarism if the original source is not properly acknowledged. So you can be held accountable for plagiarizing material in either a final submission of an assignment or a draft that is being submitted to an instructor for review, comments, and/or approval. Using verbatim material (e.g., exact words) without proper attribution (or credit) constitutes the most blatant form of plagiarism. However, other types of material can be plagiarized as well, such as ideas drawn from an original source or even its structure (e.g., sentence construction or line of argument). FIN 367 – Fall 2014 Ritter page 12 Improper or insufficient paraphrasing often accounts for this type of plagiarism. (See additional information on paraphrasing.) Plagiarism can be committed intentionally or unintentionally. Strictly speaking, any use of material from another source without proper attribution constitutes plagiarism, regardless why that occurred, and any such conduct violates accepted standards of academic integrity. Some students deliberately plagiarize, often rationalizing this misconduct with a variety of excuses: falling behind and succumbing to the pressures of meeting deadlines; feeling overworked and wishing to reduce their workloads; compensating for actual (or perceived) academic or language deficiencies; and/or justifying plagiarism on other grounds. But some students commit plagiarism without intending to do so, often stumbling into negligent plagiarism as a result of sloppy note taking, insufficient paraphrasing, and/or ineffective proofreading. Those problems, however, neither justify nor excuse this breach of academic standards. By misunderstanding the meaning of plagiarism and/or failing to cite sources accurately, you are much more likely to commit this violation. Avoiding that outcome requires, at a minimum, a clear understanding of plagiarism and the appropriate techniques for scholarly attribution. (See related information on paraphrasing; note taking and proofreading; and acknowledging and citing sources.) By merely changing a few words or rearranging several words or sentences, you are not paraphrasing. Making minor revisions to borrowed text amounts to plagiarism. Even if properly cited, a "paraphrase" that is too similar to the original source's wording and/or structure is, in fact, plagiarized. (See additional information on paraphrasing.) Remember, your instructors should be able to clearly identify which materials (e.g., words and ideas) are your own and which originated with other sources. That cannot be accomplished without proper attribution. You must give credit where it is due, acknowledging the sources of any borrowed passages, ideas, or other types of materials, and enclosing any verbatim excerpts with quotation marks (using block indentation for longer passages). Plagiarism & Unauthorized Collaboration Plagiarism and unauthorized collaboration are often committed jointly. By submitting as your own work any unattributed material that you obtained from other sources (including the contributions of another student who assisted you in preparing a homework assignment), you have committed plagiarism. And if the instructor did not authorize students to work together on the assignment, you have also engaged in unauthorized collaboration. Both violations contribute to the same fundamental deception—representing material obtained from another source as your own work. Group efforts that extend beyond the limits approved by an instructor frequently involve plagiarism in addition to unauthorized collaboration. For example, an instructor may allow students to work together while researching a subject, but require each student to write a separate report. If the students collaborate while writing their reports and then submit the products of those joint efforts as individual works, they are guilty of unauthorized collaboration as well as plagiarism. In other words, the students collaborated on the written assignment without authorization to do so, and also failed to acknowledge the other students' contributions to their own individual reports. Multiple Submissions Submitting the same paper (or other type of assignment) for two courses without prior approval represents another form of academic dishonesty. You may not submit a substantially similar paper or project for credit in two (or more) courses unless expressly authorized to do so by your instructor(s). (See Section 11-802(b) of the Institutional Rules on Student Services and Activities for the University's official definition of scholastic dishonesty.) You may, however, re-work or supplement previous work on a topic with the instructor's approval. Some students mistakenly assume that they are entitled to submit the same paper (or other assignment) for two (or more) classes simply because they authored the original work. Ritter FIN 367 – Fall 2014 page 13 Unfortunately, students with this viewpoint tend to overlook the relevant ethical and academic issues, focusing instead on their own "authorship" of the original material and personal interest in receiving essentially double credit for a single effort. Unauthorized multiple submissions are inherently deceptive. After all, an instructor reasonably assumes that any completed assignments being submitted for credit were actually prepared for that course. Mindful of that assumption, students who "recycle" their own papers from one course to another make an effort to convey that impression. For instance, a student may revise the original title page or imply through some other means that he or she wrote the paper for that particular course, sometimes to the extent of discussing a "proposed" paper topic with the instructor or presenting a "draft" of the paper before submitting the "recycled" work for credit. The issue of plagiarism is also relevant. If, for example, you previously prepared a paper for one course and then submit it for credit in another course without citing the initial work, you are committing plagiarism—essentially "self-plagiarism"—the term used by some institutions. Recall the broad scope of plagiarism: all types of materials can be plagiarized, including unpublished works, even papers you previously wrote. Another problem concerns the resulting "unfair academic advantage" that is specifically referenced in the University's definition of scholastic dishonesty. If you submit a paper for one course that you prepared and submitted for another class, you are simply better situated to devote more time and energy toward fulfilling other requirements for the subsequent course than would be available to classmates who are completing all course requirements during that semester. In effect, you would be gaining an unfair academic advantage, which constitutes academic dishonesty as it is defined on this campus. Some students, of course, do recognize one or more of these ethical issues, but still refrain from citing their authorship of prior papers to avoid earning reduced (or zero) credit for the same works in other classes. That underlying motivation further illustrates the deceptive nature of unauthorized multiple submissions. An additional issue concerns the problematic minimal efforts involved in "recycling" papers (or other prepared assignments). Exerting minimal effort basically undercuts the curricular objectives associated with a particular assignment and the course itself. Likewise, the practice of "recycling" papers subverts important learning goals for individual degree programs and higher education in general, such as the mastery of specific skills that students should acquire and develop in preparing written assignments. This demanding but necessary process is somewhat analogous to the required regimen of athletes, like the numerous laps and other repetitive training exercises that runners must successfully complete to prepare adequately for a marathon.” Ritter FIN 367 – Fall 2014 Short Bio John Ritter, Esq., CFA Lecturer Department of Finance • MBA, University of Texas Graduate School of Business, 1994 • JD, University of Texas School of Law, 1994 • BS, University of Texas, 1991 CFA - 2002 page 14 Ritter FIN 367 – Fall 2014 page 15 Academic Dishonesty Academic dishonesty will not be tolerated. Any individual suspected of cheating, including stealing or using stolen examinations, will be disciplined to the maximum extent possible. Review UT Honor Code at http://registrar.utexas.edu/catalogs/gi09-10/ch01/index.html The McCombs School of Business has no tolerance for acts of scholastic dishonesty. The responsibilities of both students and faculty with regard to scholastic dishonesty are described in detail in the Policy Statement on Scholastic Dishonesty for the McCombs School of Business: By teaching this course, I have agreed to observe all of the faculty responsibilities described in that document. By enrolling in this class, you have agreed to observe all of the student responsibilities described in that document. If the application of that Policy Statement to this class and its assignments is unclear in any way, it is your responsibility to ask me for clarification. Policy on Scholastic Dishonesty: Students who violate University rules on scholastic dishonesty are subject to disciplinary penalties, including the possibility of failure in the course an/or dismissal from the University. Since dishonesty harms the individual, all students, and the integrity of the University, policies on scholastic dishonesty will be strictly enforced. You should refer to the Student Judicial Services website at http://deanofstudents.utexas.edu/sjs/ or the General Information Catalog to access the official University policies and procedures on scholastic dishonesty as well as further elaboration on what constitutes scholastic dishonesty. Students with Disabilities Upon request, the University of Texas at Austin provides appropriate academic accommodations for qualified students with disabilities. Services for Students with Disabilities (SSD) is housed in the Office of the Dean of Students, located on the fourth floor of the Student Services Building. Information on how to register, downloadable forms, including guidelines for documentation, accommodation request letters, and releases of information are available online at http://deanofstudents.utexas.edu/ssd/index.php. Please do not hesitate to contact SSD at (512) 471-6259, 471-6441 TTY or via e-mail if you have any questions. Religious Holidays By UT Austin policy, you must notify me of your pending absence at least fourteen days prior to the date of observance of a religious holiday day. If you miss a class, an examination, a work assignment or a project in order to observe a religious holiday day, you will be given an opportunity to complete the missed work within a reasonable time after the absence.