DOC - Epsom College Intranet

advertisement

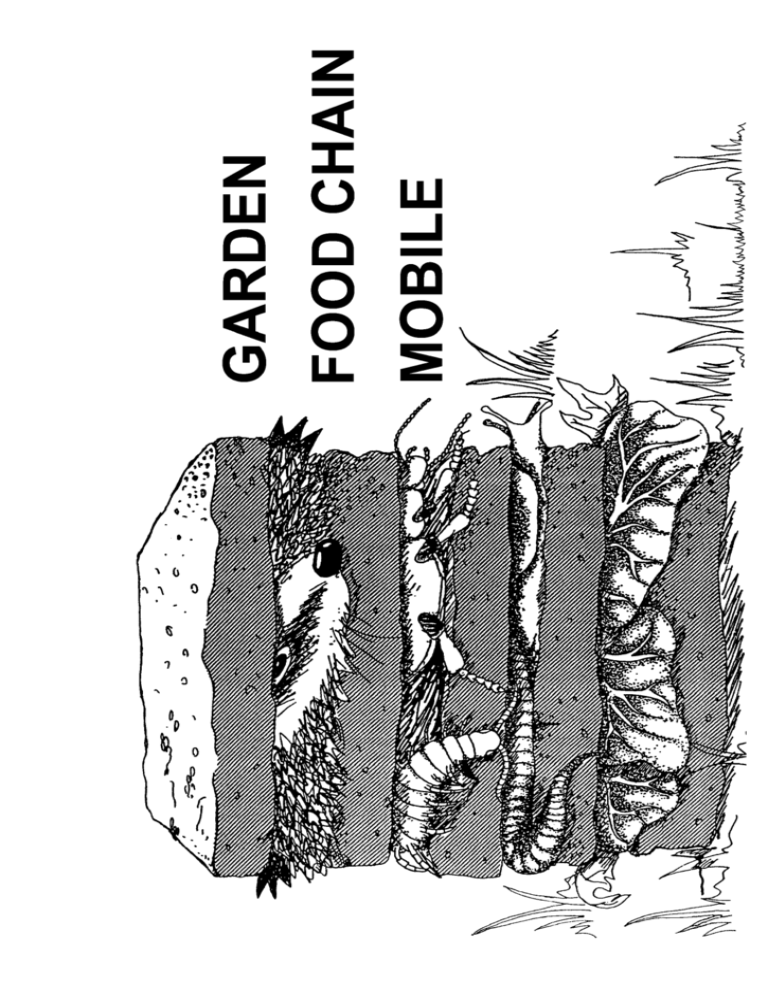

E244cs Garden Food Chain Mobile (Colour version) Contents 1. Page Background notes ........................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Decomposing vegetation ..................................................................................... 2 1.2 Mites ....................................................................................................................... 3 1.3 Springtails .............................................................................................................. 3 1.4 Earthworms ........................................................................................................... 4 1.5 Snails ....................................................................................................................... 5 1.6 Slugs........................................................................................................................ 6 1.7 Centipedes ............................................................................................................. 6 1.8 Ants ......................................................................................................................... 7 1.9 Carabid beetles ...................................................................................................... 8 1.10 Hedgehogs ............................................................................................................. 9 2. References for further reading .................................................................................... 10 3. Instructions for construction ....................................................................................... 11 4. Garden food chain organisms ..................................................................................... 13 5. Garden food chain mobile cut-out pictures .............................................................. 15 Acknowledgements This guide was originally published by the ILEA Centre for Life Studies. Following the closure of the Centre, CLEAPSS has been able to acquire the copyright of all the CLS publications. Original design and artwork by Bernice Holloway, now working at Sir Henry Floyd Grammar School. Strictly Confidential Circulate to members and associates only As with all CLEAPSS materials, members and associates are free to copy all or part of this guide for use in their own establishments. © CLEAPSS® 2005 CLEAPSS® The Gardiner Building Brunel Science Park Uxbridge UB8 3PQ Tel: 01895 251496 Fax: 01895 814372 E-mail: science@cleapss.org.uk Web site: www.cleapss.org.uk BACKGROUND NOTES The materials in this kit, when cut out and hung together, form a mobile that illustrates some of the many organisms that can be found in a garden, woodland or hedgerow habitat and the various feeding relationships between them. Naturally, the organisms chosen for the garden mobile are only a small sample of the animal communities present in such a habitat in which feeding links would be much more complex. All the organisms form FOOD CHAINS, which in turn are linked into food webs as follows. HEDGEHOG CARABID (GROUND) BEETLE CENTIPEDE SLUG ANT EARTHWORM MITE SPRINGTAIL SNAIL FUNGI & BACTERIA DECAYING VEGETATION DEATH PLANTS 1 A food chain can be relatively short: Plants Slugs Hedgehog Plants Fungi Mites Hedgehog Carabid beetles or longer: Ants All of the organisms illustrated in the mobile depend ultimately on plant material which, by taking in carbon dioxide, water and minerals, has synthesised its own foods using sunlight energy. Herbivorous animals feed on the plants and in turn are eaten by the carnivores. Many animals require vegetation to be in a state of decay, caused by the decomposers - bacteria and fungi. Most of the animals illustrated are inhabitants of the soil or leaf litter and will rarely be immediately visible. In addition, many are nocturnal in their movements, but a careful investigation of the wildlife beneath leaves, stones and pieces of wood will reveal all of the animals described here, and many more besides! DECOMPOSING VEGETATION When plant material dies, millions of microorganisms invade the tissues and begin to feed on it. These include various bacteria and the threads or hyphae of fungi. Together these form the DECOMPOSER organisms and by their actions they decay dead plants and animals and release materials into the soil which can be reutilised by plants. Most of the soil bacteria are rod-shaped and have a length between 1 and 3 µm (micrometres) (1 µm =1/1000 mm). Generally most bacteria survive best in neutral or slightly alkaline soils. In sandy or acidic soils they are less common and, as a result, vegetation decays here much more slowly. The fungal hyphae can penetrate right inside plant cells, release digestive enzymes to break down the cell walls and contents, and then absorb the digested products for food. Many organisms rely on the combined action of bacteria and fungi to begin the breakdown of the resistant cellulose of plant cell walls. Once this decomposition has begun, cells are broken apart, materials are released, and the decaying vegetation becomes a more readily accessible source of food. 2 MITES Mites are arthropods and belong to the ARACHNID class which includes spiders and harvest men. Their size usually varies from 0.1 mm to 2 mm in length but most are very small. They are oval in shape and often have no clear body sub-divisions, unlike other arachnids. Identification of individuals is not easy and the various sensory hairs (setae) on the body are used to distinguish different species. The mites’ life cycle involves a larva-like animal emerging from the egg which only has three pairs of legs - unlike subsequent stages and adults which have the four pairs characteristic of arachnids. Following the ‘larval’ stage, there are three stages of nymphs in which the mite resembles the final adult form but is much smaller. The body covering is shed by moulting between each phase of the lifecycle. The majority of mites feed on decaying vegetation, fungal hyphae and simple plants - the algae, but there are many species which have piercing mouth parts and feed on the cell sap of living plants. (For simplicity, the mobile does not attempt to show this direct feeding link with living plants.) There are also many parasitic mites which attack the external parts of their animal hosts and an abundance of mites in houses feed on human sloughed skin cells and hair fragments in dust. SPRINGTAILS The springtails are very primitive wingless insects belonging to the COLLEMBOLA group. They are very numerous in the soil and leaf litter and have a hairy cylindrical grey or yellowish body up to about 5 mm in length. They get their name because most (but not all) species possess a forked springing organ which, when not in use, is held beneath the body in a small groove. When disturbed the animal releases its ‘tail’ which springs downwards and backwards propelling the insect forward quite vigorously. Springtails consume a wide variety of organic food according to availability but feed mainly on decaying vegetation. They show incomplete metamorphosis with a small nymph hatching from the egg which resembles the adult in all but size and body pigment. At each moult, the nymphs become larger and more deeply pigmented until the adult stage is reached. The number of juvenile stages is variable depending on the species. 3 EARTHWORMS There are about 25 species of British earthworm which all look fairly similar but vary considerably in size (from a few centimetres up to 30 cm) and to some extent colour. Earthworms are ANNELIDS - the segmented worms - and are related to leeches. They belong to the oligochaete class of annelids which means having ‘few bristles’. The earthworms do, however, possess bristles or chaetae - 4 pairs on each segment except the first and last - which are used to grip the soil surface in movement; these are not, however, very visible. All earthworms have a cylindrical body, pointed at the front end as an adaptation for burrowing through the soil. The anterior mouth is covered by the prostomium - a fleshy flap. The number of segments in the earthworm varies from species to species and also according to age and size. In mature worms, a swelling develops at some point along their length called the saddle or clitellum which plays an important role in reproduction. The earthworms feed by swallowing soil as they burrow and digesting bacteria and decaying vegetation within the soil. Indigestible mineral matter is egested from the posterior of the animals in the upper parts of their burrows. Only a couple of species of earthworm called Allolobophora produce the familiar worm casts on the soil surface. By this deposition of soil at or near the surface, earthworms return minerals to the region where plant roots are growing, counteracting the effects of rainfall which tends to carry dissolved minerals deeper into the soil. In this way, earthworms aid plant growth, as well as promoting good aeration and drainage because of their tunnels. The earthworms’ behaviour of bringing the soil to the surface eventually leads to stones and other large objects being buried. Darwin estimated that this burying rate of stones is about 5 mm per year. Earthworms do not spend all their time in their burrows. On warm, moist evenings they often can be found on the soil surface with their rear ends firmly anchored in their tunnels. They regularly drag dead leaves back into their burrows either to block the entrance or to use as an additional source of food as they decay. The most common and largest garden earthworms, Lumbricus terrestris, can sometimes be seen mating on the soil surface. Earthworms are hermaphrodites having both male and female sexual organs and, when mating, they lie head to tail so that sperm can be transferred from one animal to the other. The animals then part and later a cylinder of mucus is produced around the worm by the clitellum. The worm moves through this belt, depositing both eggs and sperm inside to produce a cocoon surrounding the fertilised eggs which may number up to 20. These hatch in a few weeks or months. By their mating actions at the surface, some worms increase their risks of predation considerably but most species mate in the safety of their burrows. 4 SNAILS All land snails belong to the MOLLUSC group which is largely aquatic and includes the octopus, squid and bivalves such as mussels. Snails are called gastropods which literally means ‘stomach foot’ as they have a strong muscular ‘foot’ on which they glide about and inside which is their large gut. There are about 80 species of British snail with a wide variety of shapes, colours and sizes to their shells. The smallest adult snails have a shell height of about 5 mm, the largest - the edible or Roman snail - about 50 mm. The common garden snail, Helix aspersa, has a shell height of up to 40 mm. The spiral shells may be very flattened or have a conical or almost spherical shape. Colours can be very variable even within the same species with most shells being brown, yellow or cream, often with striped banding or mottled patterns. The colours and the patterns are thought to aid camouflage. Snails are largely nocturnal, resting out of sight in cool, moist areas in the daylight hours. They will, however, become active during the day in wet weather. The majority of British land snails are herbivorous, feeding on a wide variety of vegetation, both living and decaying. (For simplicity, the snail is shown in the mobile feeding just on living plants.) A few species are carnivorous, feeding on other snails and their eggs. Snails require calcium carbonate in their diet to provide the raw material for their shells. They are rarely found in areas with very acid soils, being most common on lime-rich alkaline soils. The larger species, such as the edible snail with its larger calcium requirements, are usually restricted to areas with very chalky soils. In unfavourable weather or when danger threatens, the snails retreat into their shells, and may seal up the opening with layers of mucus which harden. Snails are hermaphrodites and mating often involves a ritual courtship ‘dance’ lasting several hours. During this, the snails raise the front parts of their bodies and press the soles of their feet together. A ‘love dart’, which is thought to trigger sperm release, is ‘fired’ and penetrates the skin of the partner. On average about 30-40 eggs are laid (but with some species it may be as many as 100), each encased in a chalky shell, and deposited in shallow burrows made in the soil. The young snails, which are identical to the adult except in size, emerge within a month and eat their egg shells first (which provides an immediate source of calcium carbonate for their shell growth). As the snail grows, it adds chalky material to the leading edge of the shell, enlarging it in a spiral pattern. Growth lines can be seen on the shell, the spacing of which represents when growth slowed down during the winter or a long dry spell in the summer. 5 SLUGS Slugs are essentially snails without shells, though some species do have a small plate-like shell beneath the skin on the back of the body. Garden slugs rarely exceed 5 cm in length and many smaller specimens, measuring just 1-2 cm, are common. They are usually black or grey in colour, though some have a variable colour from white to dark brown. Several species such as the field slug feed at the soil surface, others such as the garden and keeled slugs generally keep below ground. In wet weather, however, and during the night, many slugs will venture out and feed above ground. A wide range of plant material including leaves, fruit and tubers is eaten, as well as decaying vegetation. Slugs also seem to have a fondness for beer! Slugs are less restricted in their distribution than snails because they do not need large quantities of lime in their diet. The absence of a shell enables them to move into small crevices not accessible to snails and so escape predation in this way as well as producing distasteful mucus which discourages some predators. CENTIPEDES These joint-legged arthropod animals belong to the MYRIAPOD (many feet) group which also includes the herbivorous millipedes. The centipedes are called chilopods and have one pair of legs per body segment (as compared with the two pairs in millipedes). Depending on the species, centipedes have anything between 15 and 101 pairs of legs. There are 44 British species, the most familiar, such as Lithobius, having a shiny, flattened, dark or reddish brown body about 3 cm in length. Centipedes move around at night on the soil surface and can be found during the day beneath leaves and stones, sheltering from the drying effects of the Sun. They are restricted to damp areas because, when exposed, they lose moisture very quickly and die. They have a marked aversion to light. Other types of centipede are subterranean in habit and have a more delicate body with larger numbers of legs. They may be bright yellow in colour and reach a length of 7 cm. Centipedes are generally carnivorous though some subterranean species may attack root crops. They have sharp-pointed fangs which are in fact specially adapted fore legs. A wide variety of invertebrates is preyed upon, including insects, slugs and snails, spiders and earthworms. (In order to keep the mobile to a manageable size, the centipede is illustrated as feeding only on three organisms. This is not meant to imply that it feeds exclusively on these animals.) The prey is seized by the fangs and passed back to the biting mandibles, or sometimes held secure by throwing body coils around the prey as with a constricting snake. (This is more usual with the larger subterranean species.) Cannibalism is not uncommon. 6 Centipedes can move very quickly (up to 50 cm per second in Scutigera which has very long legs) and use their speed effectively to chase after prey (which are usually detected by scent and touch) and also to escape from predation by larger animals. Centipede reproduction involves the production of a packet of sperm which the female takes up from the silk web on which it was placed by the male. Eggs are often laid singly in the soil. The young centipedes are immediately active and, in the surface-active species, are independent of their parents. Subterranean species may protect their young until after they have grown a little and moulted. ANTS There are about 40 species of ants in the UK and these vary in size depending on the species and also on the status of the animal within the colony. The smallest ants are a few millimetres; the largest, which are the wood ants, are 12 mm in length. A variety of species is regularly found in gardens, woodlands and hedgerows including the black garden ant, Lasius niger, the common red ant, Myrmica ruginodis, the yellow meadow ant, Lasius flavus, and the wood ant, Formica rufa, which has distinctive red and black markings. The ants belong to the HYMENOPTERA group of insects, which also includes bees and wasps. Where these insects have wings, they have two pairs. There are three types of ant in the colony: winged queens (one or more but always a restricted number), workers which are wingless females, and males at certain times of the year (May to September) which have wings and are the smallest. It is most likely that ants found outside the nest will be workers - it is these ants which forage for food, tend the queen, rear the offspring and maintain the nest. The queen is essentially an egg-laying machine and the males’ sole function is to mate with the queen. Males are only produced in the summer when the female can produce unfertilised eggs which will become males. Fertilised eggs develop into workers or other queens. Mating occurs outside the nest in the summer in warm, humid conditions. Males and queens emerge and generally mate in the air, though some species appear to mate on the ground after the nuptial flight. The males, once mated, soon die and the queens lose their wings and return to the old nest or attempt to find a fresh site to form a new colony. Sufficient sperm are stored from this single mating for the queen to use when laying thousands of eggs throughout the rest of the year. As the queen lays eggs, these are carried away by workers to special chambers in the nest. The larvae which hatch are fed on the larvae of other insects and honeydew which workers solicit from aphids by stroking them with their antennae. Mature larvae pupate inside silk cocoons (the ‘ants eggs’ used to feed aquarium fish). 7 Worker ants leave the nest to forage for food and may travel quite extensive distances (50 - 100 metres). The trails they use lead to plants where aphids are feeding (and provide the ants with honeydew), to flowers where nectar is collected, or to trees or other areas where a variety of insects may be found and captured with the strong jaws. These include larvae of many species, flies and moths, together with a large number of mites. (In this mobile, only the feeding link with mites is illustrated.) A large amount of food is collected each day by the entire work force - as much as 1 kilogram of insects per day for a large colony of wood ants! When food is plentiful, separate ant colonies keep to their own territories but, when food is scarce, marauding trips into neighbouring hunting grounds may be made - leading to extensive battles between opposing ones. Some species, including the meadow ant, remain in their nests for much of the time and instead of foraging outside for food, nurture large numbers of aphids within the nest and milk these for the honeydew that they secrete. CARABID BEETLES Carabid or ground beetles belong to the COLEOPTERA order of insects which generally have a thickened pair of wing cases or elytra meeting along the back in a straight line and protecting a second pair of delicate wings underneath. All carabids are efficient hunters, having large jaws, long legs for rapid movement and long sensitive antennae. They are largely nocturnal animals and consequently most are a shiny black or drab brown in colour. There are some species, however, which have a more spectacular colouration with metallic green, bronze or purple patches on their elytra. The carabid illustrated in the mobile is the violet ground beetle, Carabus violaceus, which is about 3 cm in length and has a characteristic violet flush along the edge of its wing cases. Other carabids are usually smaller than this with several that are 5 mm and many about 1 - 2 cm. All carabids prey on a wide range of invertebrates including slugs, snails, worms, woodlice, ants and a variety of other insects. They will regularly attack and kill animals that are many times their own size. On warm, wet evenings the larger species such as the violet ground beetle are particularly active, hunting earthworms that have left their burrows and attacking snails and slugs out feeding on plants - even climbing trees in search of prey! Only some of the possible prey organisms of carabid beetles have been shown in the mobile. Carabid beetles have a ‘complete’ life cycle with larvae becoming pupae from which the adults emerge. The larvae are aggressive hunters like the adults with either soft white, or hard black, bodies and three pairs of legs. They develop from eggs laid in the soil or decaying wood and vegetation and hunt small invertebrates in the soil and leaf litter. 8 HEDGEHOGS Hedgehogs are common in woodlands and hedgerows and far more common in urban gardens than many people realise, even right in the centre of very built-up areas. Being nocturnal, their activities are not often noticed unless they reveal their presence by squealing like a pig which they can do when they are unduly frightened or making loud snorting noises when mating. The hedgehog, Erinaceus europaeus, reaches a body length of about 26 cm in the male and between 800 - 1110 g in weight. Females are slightly smaller and weigh between 560 and 700 g. They have an overall brown colour with dark brown spines that have lighter tips. The head and underbelly fur is coarse and a pale brown colour. The hedgehog’s nocturnal behaviour is more likely to be linked to its food supply than a need to protect itself in the dark from potential predators - its spines usually prevent any serious attacks. At night, particularly when warm and humid, many invertebrates will be active and virtually all seem to be eaten. Particularly tasteful are worms, slugs, caterpillars, centipedes and millipedes, beetles and a variety of other insects. Woodlice and snails seem, however, to be less popular. Hedgehogs will also take a wide variety of other foods including bird table scraps plus cat and dog food. They are particularly fond of bread and milk left out for them and this can be used to attract hedgehogs close to a house for observation of their activity. Food is identified and tracked down by using the hedgehog’s acute sense of smell and hearing. Eyesight is not particularly good. Some of the hedgehog’s prey animals are illustrated in the mobile, but it would be clearly impossible to show them all (including bottles of milk and loaves of bread!). Hedgehogs will travel quite long distances at night in search of food (e.g. up to a couple of miles) and can run faster than a human walking, swim, burrow and climb over 2 metre-high fences or walls. They do not set up and defend territories but they do establish social hierarchies, e.g. when several individuals regularly feed from a bowl of milk left for them. In the summer, hedgehogs regularly mate, with the male continuously circling round a stationary female for up to half an hour, and leaving a circular track in the soil as a result. With their spiny protection, hedgehogs must be careful when they mate and the female flattens her spines against her back. From now on, the male plays no part in rearing the young, four or five of which are usually born after about 31-35 days. The babies initially have about 100 white spines, which soon darken and increase up to the adult number of between three and seven thousand. The offspring are tended for about five weeks, after which they disperse to live solitarily. Lifespan is, on average, 2 years with some individuals reaching as much as 8 years old. The major threat to hedgehogs are humans - either in motor cars or as gamekeepers (who kill hedgehogs to protect their game bird eggs). There is some evidence of abnormal behaviour such as running round in circles (other than during mating) and wandering around during the day which may be the result of poisoning and a prelude to death. Poisoning may result from the increasing use of pesticides including slug pellets, which leads to many poisoned invertebrates being eaten and the toxin accumulating in the hedgehog’s fat stores. Then, as the fat is used up during the winter hibernation, the concentrated poisons are released. 9 REFERENCES FOR FURTHER READING* A Closer Look at Ants V. Pitt & D. Cook, Hamish Hamilton Animals in the Soil I. Finch, Longman Ants (Social Insects Series) Addison Wesley The Back Garden Wildlife Sanctuary Book R. Wilson, Penguin Bellamy’s Backyard Safari BBC Publications Earthworms Pugh & Tuke, School Natural Science Society Publication No. 16 Ecology of Soil Organisms A. Leadley Brown, Heinemann Educational A Field Guide to the Insects of Britain & Northern Europe M. Chinery, Collins A Field Guide to the Land Snails of Britain & North West Europe Kerney & Cameron, Collins Hedgehogs Pat Morris, Whittet Books The Life of Beetles G. Evans, Allen & Urwin Life Under Stones J. Free, A & C Black The Natural History of Britain and Europe: Towns & Gardens D. Owen, Hodder & Stoughton The Natural History of the Garden M. Chinery, Collins The Nature Trail Book of Garden Wildlife Usborne The Nature Trail Book of Insect Watching Usborne The Oxford Book of Insects Oxford University Press The Oxford Book of Invertebrates Oxford University Press Snails & Slugs E. Tuke, School Natural Science Society Publication No. 45 Urban Ecology (Biology Colour Units Series) D. Gilman, Macdonald Educational Wildlife in Towns G. Carter, Macdonald Educational * Note: This list was compiled when the Garden Food Chain Mobile was developed by the ILEA Centre for Life Studies in the 1980’s. Many of the titles will now be out of print but may be obtained from libraries or equivalent, currently-available materials substituted. 10 INSTRUCTIONS FOR CONSTRUCTION 1. Print out all the organisms on the accompanying sheets onto card using a colour printer and then cut them out. You will find that for each copy of an organism, there is another ‘reverse image’ copy. It is sensible to use the hedgehog as a template to cut out another hedgehog ‘shape’ on a thick piece of card. This is then stuck between the two hedgehog cut-outs to strengthen the construction, since all the other organisms hang from this and otherwise it might bend. Alternatively, if a laminator is available, this might be used to strengthen and protect each organism in the food chain after you have completed step 2. 2. Using a strong paper adhesive (eg, rubber cement such as ‘Fixogum’), stick the two ‘halves’ of each organism together. 3. When the adhesive has dried thoroughly, pierce holes through the positions marked on the organism cut-outs. 4. Cut appropriate lengths of fine, nylon thread (such as that used as ‘fishing line’) or cotton thread to join the organisms together into the food chain mobile. Refer to the illustration of the complete mobile for the relative lengths of each piece of thread. 5. Push the thread through the holes in the organisms and tie a tight knot for each hanging point. Join the organisms together in the sequence shown on the accompanying diagram with the hedgehog at the top of the food chain. (The illustrations of the organisms used in the mobile (page 13) can be laminated and placed on a wall, adjacent to the mobile, to identify the organisms.) 11 12 13 This page has been deliberately left blank. 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22