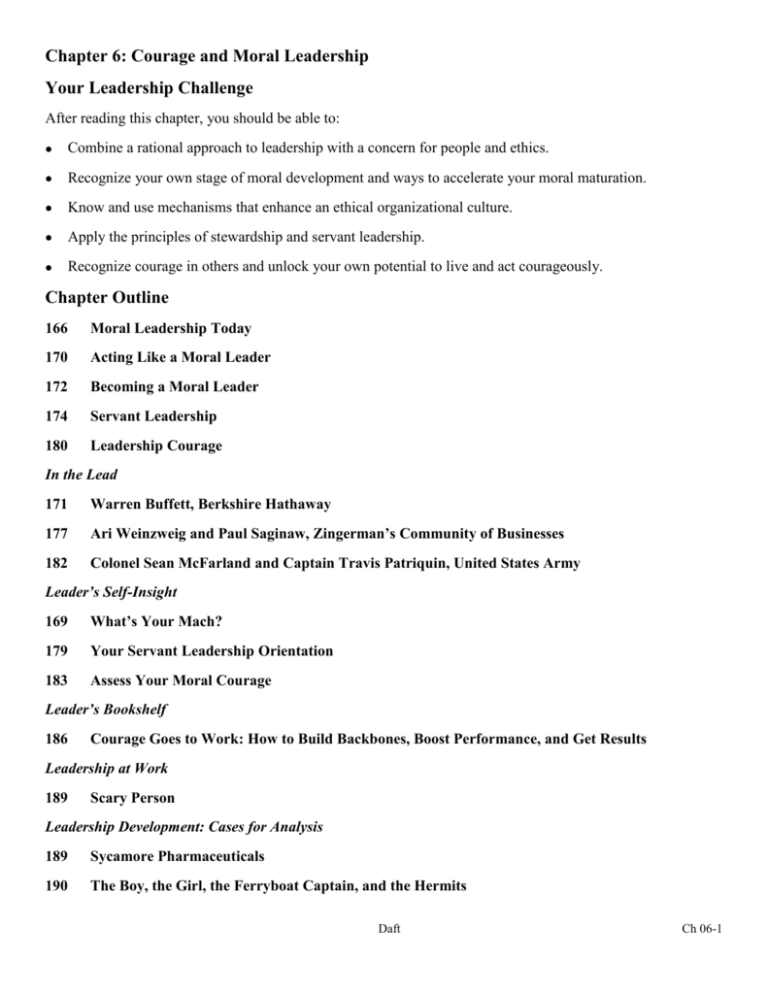

Courage and Moral Leadership: Chapter Overview

advertisement