Ian Breakwell

advertisement

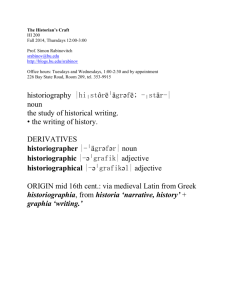

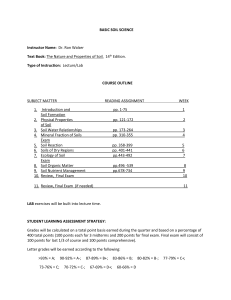

Home Introduction Keynote Speakers Symposium Overview Papers Ian Breakwell WALSERINGS A personal response, through drawings, to the life and work of the writer Robert Walser Copyright © 2000 Loughborough University and the Author 1 WALSERINGS Short prose fiction other than stories and fables is scarce; in 1988 I had difficulty quoting antecedents for the publisher's blurb of my own prose collection The Artist's Dream.1 Swift, Kafka, Beckett, Burroughs, Firbank, Artaud: the list was short and unnervingly big-league. Then those sharp booksellers, Mike and Paul in Compendium, said 'Why didn’t you mention Robert Walser?' And I replied, ‘Who?’ When I left the shop I had bought Walser's only book then in print in English: Selected Stories2 and been loaned the out-of-print American edition of his novel Jakob Von Gunten. I settled down to read and my eyebrows rose: Walser was, without doubt, one of the most intriguingly original 20th century writers. So who was he, and why is his work now so little known? Robert Walser was born in Switzerland in 1878, the son of humble working-class parents. He left school when he was 14; from 1895 until 1929 he led a peripatetic life in Zurich, Berlin and Biel, had 15 books published, and worked as a bank clerk, butler, secretary, a worker in a rubber factory and a brewery. Those jobs only lasted long enough to finance his long, solitary walks through Switzerland and Germany. In all Walser wrote eight novels, many poems, and over a thousand short prose pieces written in a microscopic shorthand script, many of which have still not been deciphered. His admirers included Kafka, Thomas Mann, Walter Benjamin, and Herman Hesse who said of him: 'If he had a hundred thousand readers the world would be a better place'. But his uncompromising lack of conventional ambition, and a prose style radically at odds with the times, meant that his writing earned him little. By 1929 he was working in poverty in an unheated attic room, dressed in a military greatcoat, and shoes which he made out of bits of old clothing. Plagued by hallucinations and nightmares, he made several suicide attempts before voluntarily committing himself to Waldau Sanatorium, where he was diagnosed as schizophrenic. In 1933 he was transferred, against his wishes, to another hospital, after which he never wrote again. To his legal guardian Carl Seelig, he said, 'I am not here to write but to be mad'. He died in the snow while out walking alone in the hospital grounds on Christmas Day 1956, a demise he had foretold with uncanny accuracy in the prose piece "A Christmas Story"3 forty years earlier. Copyright © 2000 Loughborough University and the Author 2 So finally, in a snowdrift, Walser attained his lifelong ambition: oblivion. This desire to become a zero is the theme of his novel Jakob Von Gunten, retitled Institute Benjamenta4 in 1995 when it was republished to coincide with the Quay Brothers' feature film of the book. Institute Benjamenta is the impromptu, first-person journal of Jakob, a boy attending a school for butlers (as Walser did in real life). Yet it seems to be the school's contrary function to teach the pupils nothing. Frustrated at every turn, Jakob rambles incessantly on about the trivialities, enigmas and disorientation of his everyday life, and finally finds acceptance in the eyes of the principal, Herr Benjamenta, only when he relinquishes every desire to understand. The theme of the Underdog and Authority appealed to Kafka, but Walser's prose remains unique. This master of the absurd wrote his celebrations of the insignificant and the antiheroic, not in his native Swiss but in High German, the language of civic authority and public speeches. Walser's is an oscillating verbal style which simultaneously creates and cancels meaning. ... If I want to, if I tell myself to, I can revere everything, even bad behaviour, but it must be the colour of money. Meandering rhapsodic reverie is abruptly deflated by self-referential commentary. 'That’s very poetic.' Convoluted musings riddled with contradiction are set beside exquisitely modulated prose. Ironic detachment and mocking self-parody switch into acutely observed vignettes. The courtyard out there lies deserted, like a foursquare eternity, and I usually practice standing on one leg. Often, for a change, I see how long I can hold my breath. Not for long. Walser's writing turns on the paradox of his tortured awareness of the inadequacy of words to express true meaning and the compulsion to use them. 'I want to think of something else, that's to say, I don't want to think of anything.' There are curious echoes of Walser's ambivalent jabbering in the disembodied, obsessional chatter of roleplaying nerds on the Internet. Copyright © 2000 Loughborough University and the Author 3 Walser repeatedly implies that any coherent synthesis lies beyond verbal language, perhaps in the visual arts. Comparisons between Walser and his fellow Swiss, Paul Klee, are apt, and Walser's perverse humour has parallels with Bunuel's films, his love of paradox with Magritte's painting, This Is Not a Pipe. The dizzy perambulations which in texts such as "Kleist in Thun"5 spin towards a vortex of visionary intensity echo Van Gogh's Starry Night. But Walser's prose, with its sly cross-referencing within a relentlessly driven, improvised quest, aspires most of all to music, to great jazz players such as Sonny Rollins and particularly Thelonious Monk. It's ironic that in the 1990s it should be painting and jazz which are beset with floundering doubt and self-parody. Walser remains relevant, and it is inexplicable that so little is available in English by this heroic nobody whom Susan Sontag rightly called 'a truly wonderful, heartbreaking writer'.6 Walser said: My writing is wallpapering... My prose pieces are parts of a long, plotless, realistic story. The novel I am constantly writing is always the same one, and it might be described as a variously sliced-up or torn apart book of myself. But who is myself? Walser's character, like his skittish, self-effacing writing, remains elusive, evasive, difficult to pin down. His original ambition was to be an actor, and he is adept at ironic disguise: when his writing reads most like a tourist brochure is when it is most mysterious. There is a concealed text on the unseen reverse of his picture postcards. It was Walser's personification of the flâneur, the wandering, amused voyeur of seemingly insubstantial and inconsequential subject matter transformed by deadpan humour, with which, through my Diaries,7 I felt a particular kinship. The Walking Man, in various guises had also been a preoccupation in my visual work for over twenty years. Subconsciously I knew that this Walking Man was a disguised mirror image of me. It seemed to me that the lengthy analysis of Walser by academics and psychologists was irrevocably flawed by the means they employed: yet more words trying to unravel the convoluted web of Walserian word play. In 1991 I decided to see if I could portray Walser, the man, visually. Copyright © 2000 Loughborough University and the Author 4 Walserings. 1991. 27 drawings, ink and gouache on paper, smallest 15 x 9 cm, largest 19 x 18 cm I began with a pen and wash 'copy' of the one photograph of Walser I had (on the back of the Selected Stories): a head and shoulders right profile as a young man. The second drawing was how I imagined his left profile. Then I imagined him full face and, using black and white watercolour and ink, progressed, like one of Walser's meandering walks, on a series of imagined facial portraits of him throughout his life to his death mask. I captioned the drawings with handwritten extracts from his writings, with a free abstract interpretation of his microscript as a microbe script 'wallpaper' backdrop. Unknowingly, until it was pointed out to me, by the time the series of watercolours had reached Walser's middle age, the pictures had become self-portraits. The drawing I was constantly making, to paraphrase Walser, was always the same one, a variously sliced-up or torn apart picture of myself. This discovery unnerved me, but although I then Walser's Walk. 1992. Oil, ink and pastel on paper, 165 x 66 cm made a conscious effort not to portray myself, my face continued to merge with Walser's mask. Copyright © 2000 Loughborough University and the Author 5 After completing the watercolour series, 27 in all, I made one last attempt in 1992 to objectively portray Walser in a large, full-length silhouette profile portrait of him in overcoat and bowler hat, carrying an umbrella and smoking a cigarette, the smoke from which forms a darkening cloud above his head, from which fall autumn leaves. Calligraphic overlays spell out Walser's words: 'Evening is now beginning to fall upon my walk and its quiet end, I think, cannot anymore be very far away'. No one has yet identified this picture as a self-portrait, for it does not look like me, yet for me it is the picture most clearly of 'myself'. Ian Breakwell July 1998 NOTES The quotations of Robert Walser's writings are taken from the books The Walk and Institute Benjamenta (both pub. Serpents Tail), and Masquerade and Other Stories (pub. Quartet). REFERENCES 1 Ian Breakwell The Artist's Dream Serpents Tail, 1988. 2 Robert Walser Selected Stories Carcanet, 1982. Republished in paperback as The Walk Serpents Tail, 1992. 3 Robert Walser "A Christmas Story" in Gesamtwerk 9, 1919 (untranslated). 4 Robert Walser Institute Benjamenta Serpents Tail, 1995. 5 Robert Walser "Kleist in Thun" in Selected Stories and The Walk, op. cit. 6 Susan Sontag in Foreword to Selected Stories, op. cit. 7 Ian Breakwell Ian Breakwell’s Diaries Pluto Press, 1986. Copyright © 2000 Loughborough University and the Author 6