String ERJ

advertisement

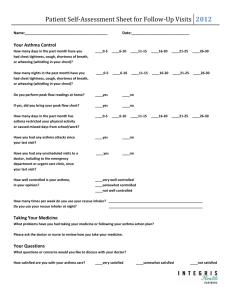

EUROPEAN RESPIRATORY JOURNAL October issue (Vol. 26, Number 4) Good news: After twenty years on the rise, child asthma seems now to be declining The steady rise in asthma rates, a trend which has been seen over the last fifteen years, may now be reversing. This study finds the clearest indications of this in young children, but the same may also apply to older age groups. This encouraging development could be the result of better diagnoses and improved treatment. On the basis of various data sources, such as hospital admissions, family doctors’ diagnoses, clinical symptoms suggestive of asthma or, even more objectively, the identification of an increased reactivity to allergens or other stimuli, researchers have generally reported an annual increase in asthma cases of approximately 5% for all ages taken together. “Since this is the commonest chronic disease affecting children, and since it has serious social and economic consequences, the trend provided strong grounds for concern,” emphasises one of the article’s authors, Onno van Schayck of the Caphri Research Institute at Maastricht University in The Netherlands. Yet things seem to be getting better, judging by the ERJ article written by van Schayck, together with Henriëtte A. Smit of the National Institute for Public Health in Bilthoven. Trend reversed Their work drew on two separate databases: the Nijmegen Continuous Morbidity Registration and regular health surveys conducted in the southern part of The Netherlands province of Limburg. The first database provides standardised accounting of all diseases affecting the region’s population. Since healthcare in The Netherlands can only be accessed through a family doctor with whom the patient must be registered, the database is a good reflection of the real situation. Analysis of the data from this source (most vividly illustrated by the graph that accompanies the article, demonstrating that asthma is also becoming less prevalent in young adults) shows a clear rise in asthma rates that starts in the early 1980s and mainly affects children from birth to age 14 years. “For this age group, asthma rates went up five-fold over fifteen years”, van Schayck explains, “but the most recent data show a reversal of the trend from the start of the new millennium. Here, again, it can be seen most clearly in children”. Respiratory symptoms reduced by 20% The second database used for the study was built up from the results of regular surveys of parents, conducted by the regional health authorities to determine the prevalence of respiratory problems in children aged eight to nine years. The surveys were repeated every four years from 1989 onwards, and used the same questionnaire each time. Since they were carried out in conjunction with the regular health checks provided for schoolchildren, participation rates were very high. “In 2001, we collected data on 1,102 children, or 95.5% of the target group, which was a similar level to that achieved in the previous three surveys”, explained van Schayck. “What surprised us was that, between 1989 and 2001, the percentage of children with at least one of the studied respiratory symptoms (cough, wheezing or breathlessness) had decreased by over 20%, falling from 17.4% to 13.5%. The reduction was particularly marked for wheezing, which affected 13.4% of children in 1989 and only 9.1% in 2001”. Over the same period, however, the researchers found that the percentage of wheezing children using either a bronchodilator or an inhaled corticosteroid had risen by more than 50%, increasing from 39.2% to 56%. This rise leads the authors to put forward hypotheses regarding the likely origin of such variations in child asthma prevalence. The cause? In seeking to explain the rise and then the recent fall in child asthma, one could certainly point to improved living conditions and, thus, a higher general level of hygiene, which has been suggested as a reason for the initial sharp increase in asthma prevalence. The authors emphasise, however, that the rise in asthma rates occurred mainly in the 1980s and 1990s, while the “westernisation” of our behaviour and increased focus on hygiene began several decades earlier. So the “hygiene hypothesis”, for them, is less than convincing. As to the recent reduction in respiratory symptoms, the authors believe it can be attributed to increasingly early diagnosis and rapid treatment of children, which leads to respiratory symptoms disappearing in many cases. As evidence, they point to the fact that the sharpest drop in wheezing, between 1997 and 2001, coincided with the publication of clear guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of child asthma by The Netherlands College of General Practitioners, which emphasised the importance of early treatment with inhaled corticosteroids. The encouraging message contained in this ERJ article is borne out by results from other teams, particularly those from a Swiss research group, which found that the rise in child asthma rates was apparently levelling off. These results from The Netherlands also emphasise, as do those from other teams, the potential benefits of improved diagnosis and early intervention. These, the authors conclude, are the factors that most probably underline this reduction in the rate of child asthma symptoms.