7. The Classification of languages I) Genetic classification and the

advertisement

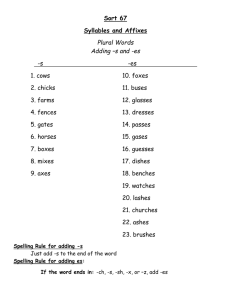

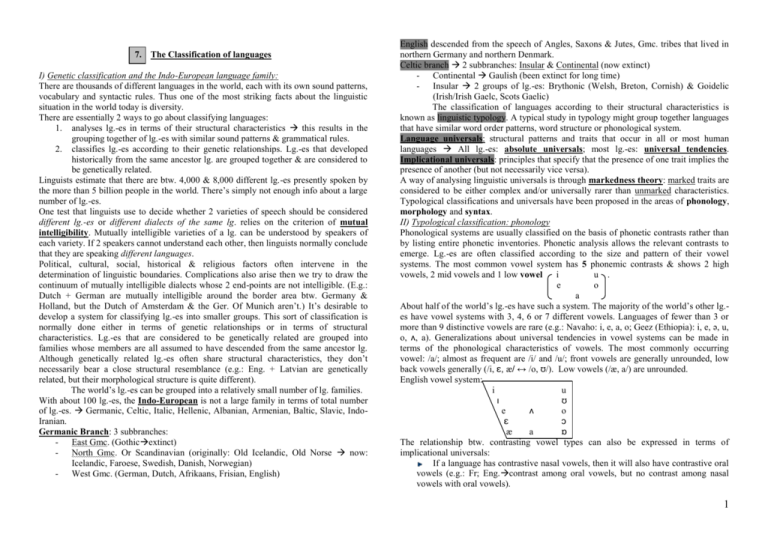

7. The Classification of languages I) Genetic classification and the Indo-European language family: There are thousands of different languages in the world, each with its own sound patterns, vocabulary and syntactic rules. Thus one of the most striking facts about the linguistic situation in the world today is diversity. There are essentially 2 ways to go about classifying languages: 1. analyses lg.-es in terms of their structural characteristics this results in the grouping together of lg.-es with similar sound patterns & grammatical rules. 2. classifies lg.-es according to their genetic relationships. Lg.-es that developed historically from the same ancestor lg. are grouped together & are considered to be genetically related. Linguists estimate that there are btw. 4,000 & 8,000 different lg.-es presently spoken by the more than 5 billion people in the world. There’s simply not enough info about a large number of lg.-es. One test that linguists use to decide whether 2 varieties of speech should be considered different lg.-es or different dialects of the same lg. relies on the criterion of mutual intelligibility. Mutually intelligible varieties of a lg. can be understood by speakers of each variety. If 2 speakers cannot understand each other, then linguists normally conclude that they are speaking different languages. Political, cultural, social, historical & religious factors often intervene in the determination of linguistic boundaries. Complications also arise then we try to draw the continuum of mutually intelligible dialects whose 2 end-points are not intelligible. (E.g.: Dutch + German are mutually intelligible around the border area btw. Germany & Holland, but the Dutch of Amsterdam & the Ger. Of Munich aren’t.) It’s desirable to develop a system for classifying lg.-es into smaller groups. This sort of classification is normally done either in terms of genetic relationships or in terms of structural characteristics. Lg.-es that are considered to be genetically related are grouped into families whose members are all assumed to have descended from the same ancestor lg. Although genetically related lg.-es often share structural characteristics, they don’t necessarily bear a close structural resemblance (e.g.: Eng. + Latvian are genetically related, but their morphological structure is quite different). The world’s lg.-es can be grouped into a relatively small number of lg. families. With about 100 lg.-es, the Indo-European is not a large family in terms of total number of lg.-es. Germanic, Celtic, Italic, Hellenic, Albanian, Armenian, Baltic, Slavic, IndoIranian. Germanic Branch: 3 subbranches: - East Gmc. (Gothicextinct) - North Gmc. Or Scandinavian (originally: Old Icelandic, Old Norse now: Icelandic, Faroese, Swedish, Danish, Norwegian) - West Gmc. (German, Dutch, Afrikaans, Frisian, English) English descended from the speech of Angles, Saxons & Jutes, Gmc. tribes that lived in northern Germany and northern Denmark. Celtic branch 2 subbranches: Insular & Continental (now extinct) - Continental Gaulish (been extinct for long time) - Insular 2 groups of lg.-es: Brythonic (Welsh, Breton, Cornish) & Goidelic (Irish/Irish Gaelc, Scots Gaelic) The classification of languages according to their structural characteristics is known as linguistic typology. A typical study in typology might group together languages that have similar word order patterns, word structure or phonological system. Language universals: structural patterns and traits that occur in all or most human languages All lg.-es: absolute universals; most lg.-es: universal tendencies. Implicational universals: principles that specify that the presence of one trait implies the presence of another (but not necessarily vice versa). A way of analysing linguistic universals is through markedness theory: marked traits are considered to be either complex and/or universally rarer than unmarked characteristics. Typological classifications and universals have been proposed in the areas of phonology, morphology and syntax. II) Typological classification: phonology Phonological systems are usually classified on the basis of phonetic contrasts rather than by listing entire phonetic inventories. Phonetic analysis allows the relevant contrasts to emerge. Lg.-es are often classified according to the size and pattern of their vowel systems. The most common vowel system has 5 phonemic contrasts & shows 2 high vowels, 2 mid vowels and 1 low vowel i u . e o a About half of the world’s lg.-es have such a system. The majority of the world’s other lg.es have vowel systems with 3, 4, 6 or 7 different vowels. Languages of fewer than 3 or more than 9 distinctive vowels are rare (e.g.: Navaho: i, e, a, o; Geez (Ethiopia): i, e, ə, u, o, ʌ, a). Generalizations about universal tendencies in vowel systems can be made in terms of the phonological characteristics of vowels. The most commonly occurring vowel: /a/; almost as frequent are /i/ and /u/; front vowels are generally unrounded, low back vowels generally (/i, ɛ, æ/ ↔ /o, ʊ/). Low vowels (/æ, a/) are unrounded. English vowel system: i u ɪ ʊ e ʌ o ɛ ɔ æ a ɒ The relationship btw. contrasting vowel types can also be expressed in terms of implicational universals: If a language has contrastive nasal vowels, then it will also have contrastive oral vowels (e.g.: Fr; Eng.contrast among oral vowels, but no contrast among nasal vowels with oral vowels). 1 If a language has contrasting long vowels, it will also have contrasting short vowels (e.g.: Finnish; Eng.contrasting short vowels, but no contrast of short with long vowels). Consonant inventories of languages may range from as few as 8 consonant phonemes (e.g.: Hawaiian) to more than 90 (! Kung, a lg. spoken in Namibia, has 96 consonant phonemes). Nevertheless, a number of claims can be made about the consonant system that occurs in human lg.: All lg.-es have stops /p, t, k/. If any of these stops is missing, it will probably /p/ (e.g.: Alent, Nubian). The most commonly occurring phoneme of the 3 is /t/. The most commonly occurring fricative phoneme is /s/, few lg.-es lack it. Almost every known lg. has at least 1 nasal phoneme; in cases where a lg. has only 1 nasal phoneme, that phoneme is usually /n/. The majority of lg.-es have at least 1 phonemic liquid; some lg.-es have none at all (Eng. has 2: /l/ & /r/). Consonant phonemes are also subject to various implicational universals: If a lg. has voiced obstruent phonemes (=> stops, fricatives or affricates), then it will also have voiceless obstruent phonemes. Sonorant consonants are generally voiced. Very few languages have voiced sonorants (e.g.: Burmese). If a lg. has fricative phonemes, then it will also have stop phonemes. Lg.-es can also be classified according to their prosodic or suprasegmental type. Lg.-es, in which pitch distinctions are phonemic, are called tone languages. Tones are of 2 types: level tones and contour tones. Tone lg.-es most often contrast only 2 tone levels (phonologically high & low), although contrasts involving 3 levels (high, low, mid) aren’t uncommon. If a lg. has contour tones, then it will also have level tones. If a lg. has complex contour tones (e.g.: rise-fall, fall-rise), then it will also have simple contour tones (rising or falling simply). Differences in stress are also useful in classifying lg.-es. Fixed stress lg.-es are those in which the position of stress on a word is predictable. In free stress lg.-es, the position of stress is not always predictable. Free stress is also called phonemic stress because of its role in distinguishing btw. words. All lg.-es permit V & CV syllable structure (V=syllabic element, C=non-syllabic element). These structures are assumed to be unmarked, since they appear in all lg.-es. If a lg. permits sequences of consonants in a syllable onset, then it will also permit single consonants or zero consonants in the onset. If a lg. permits C sequences in a syllable coda, then it will permit single consonants in a coda. III) Typological classification: morphology Combining morphemes to form words 4 types of systems, although no lg. fits any of these types perfectly: Isolating (or analytic) type: the words of the lg. consist of a single morpheme. Categories such as number & tense are usually expressed by a free morpheme (=a separate word). E. g.: Mandarin. Agglutinating type: the lg. makes use of words containing 2 or more morphemes (=a root + 1 or more affixes). Each affix is clearly identifiable & characteristically encodes a single grammatical contrast. E.g.: Turkish. Fusional type: words in a ~ or an inflectional lg. are also complex. Fusional affixes often mark several grammatical categories simultaneously. E.g.: Russian. Polysynthetic type: in a ~ lg. long strings of affixes or bound forms are united into single words, which may translate as an entire sentence in English. The use of portmanteau morphemes is common. E.g.: Inuktitut, Cree, Sarcee. Most lg.-es, including Eng., don’t belong exclusively to any of the 4 categories. A variety of generalizations can be made about word structure in human lg.: If a lg. has inflectional affixes, it will also have derivational affixes (e.g.: Eng.). If a word has both a derivational and inflectional affixes, the derivational affix is closer to the root. If a lg. has only suffixes, it will also have only postpositions. IV) Typological classification: syntax Study of word order: 3 most common word orders: SOV, SVO & VSO. All these place the subject before the Od. Subject: usually encodes the topic. (SOV Turkish; SVO Eng.; VSO Welsh.) If a lg. has VSO word order, then it will have prepositions rather than postpositions. If a lg. has SOV word order, then it will probably have postpositions rather than prepositions. In lg.-es with VSO order, adj.-es & relative clauses usually follow the N that they modify. Lg.-es with SOV order will usually place both adj.-s & relative cl.-es before the N they modify. Implicational universals are often stated in terms of hierarchies of categories or relations. One of the most important hierarchies of this type refers to the grammatical relations of Subj. + Od. Hierarchies represent degrees of markedness. least marked Subject Direct object Other most marked There are no lg.-es in which the V agrees with just the Od. 2