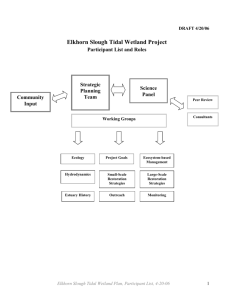

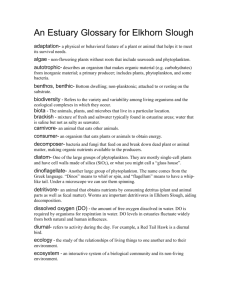

ESNERR Management Plan - Elkhorn Slough Foundation

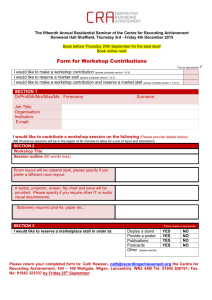

advertisement