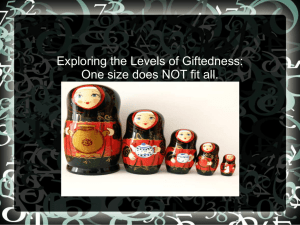

Curriculum Development for Gifted Learners

advertisement