Metabolic and cardiovascular risks with atypical antipsychotics – do

advertisement

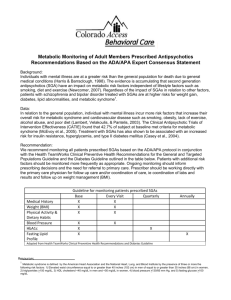

NeLM In-Focus Review Metabolic adverse effects with atypical antipsychotic agents Date Published: Author Initials: Author surname: Author affiliation: 09/05/2008 C Proudlove Medicines Information Pharmacist The Bottom Line Emerging data suggest that the risks of adverse metabolic effects, including hyperglycaemia, diabetes, weight gain and dyslipidaemia, are greater with olanzapine than other atypical antipsychotics (with the exception of clozapine). Recent changes to EU and US prescribing information for olanzapine reflect these findings. People with severe mental illness are at higher risk of cardiovascular disease than the general population. Treatment with olanzapine potentially increases the risk and this should be considered when choosing an antipsychotic agent. For the treatment of newly diagnosed schizophrenia, an agent with fewer metabolic adverse effects is preferable. However, olanzapine remains a valuable treatment option when first-line choices have failed. NICE is currently reviewing it’s guidance on the treatment of schizophrenia and publication is expected in March 2009. Background Compared to the general population, people with serious mental illness experience increased morbidity and mortality, especially due to cardiovascular disease. The risk of premature death from medical causes is at least two-fold greater in individuals with schizophrenia and bipolar disorders. Key risk factors for cardiovascular disease include obesity, dyslipidaemia, hypertension, smoking, hyperglycaemia and diabetes. The prevalence of these risk factors is higher in people with severe mental illness as they often live in poverty, have poor nutrition, and lack self- and medical-care. However, there is also evidence that antipsychotic medication, particularly atypical antipsychotics, may contribute to increased cardiovascular risk by causing weight gain, lipid abnormalities and increases in blood glucose.1 Over recent years, emerging data suggest that the risk of these metabolic adverse effects is greater with olanzapine than with other atypical antipsychotics (with the exception of clozapine) and is now recognised within US and EU prescribing information. The first changes in US prescribing information In 2003, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) asked the manufacturers of the six atypical antipsychotics then available on the US market (clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine, ziprasidone and aripiprazole) to include a warning in their prescribing information about the risks of hyperglycaemia and diabetes developing during treatment.2,3 It suggested the following wording be used “Hyperglycemia, in some cases extreme and associated with ketoacidosis or hyperosmolar coma or death, has been reported in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics……Precise risk estimates for hyperglycemia-related adverse events in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics are not available. The available data are insufficient to provide reliable estimates of differences in hyperglycemia-related adverse-event risk among the marketed atypical antipsychotics.” Although the manufacturers complied with the FDA request, some were unhappy as there was a lack of published evidence of a risk of diabetes for all drugs. In addition, clinicians were unhappy because the warning failed to address the issue of weight gain, which is considered to play a central role in the risk of diabetes, and a lack of clarity about how physicians were to manage patients who developed diabetes.4 Four US organisations (American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and North American Association for the Study of Obesity) convened a joint conference in November 2003 and published a consensus statement regarding the issue of obesity and diabetes with antipsychotic drugs. The statement was more specific than the FDA warning regarding the the risk of these adverse effects with different atypical antipsychotics and also highlighted the association between antipsychotics and dyslipidaemia.5 The consensus statement identified clozapine and olanzapine as the highest risk drugs in terms of their association with weight gain, diabetes and worsening lipid profiles. Risperidone and quetiapine were deemed to cause only moderate weight gain with evidence of drug-induced diabetes or dyslipidaemia being conflicting or non-compelling. Ziprasidone and aripiprazole were considered to have minimal effects on weight, lipids and hyperglycaemia, although the lack of long-term data was noted. A detailed monitoring protocol was recommended for patients receiving atypical antipsychotics, which is discussed later. Emerging data from new studies Subsequent to the consensus statement, the results of two important studies, CATIE6and CAFÉ7 have been published. Both studies involved long-term head-tohead comparisons of atypical agents and confirmed the higher risk of metabolic effects with olanzapine. In CATIE, 1,493 patients with schizophrenia were randomised to receive one of four atypicals or a first generation antipsychotic agent for up to 18 months, with a primary aim of delineating differences in effectiveness.6 Overall, 74% of patients discontinued study medication before 18 months. Olanzapine was the most effective antipsychotic in terms of discontinuation rates with only 64% of patients discontinuing this drug, compared to 74% of those on risperidone, 75% on perphenazine, 79% on ziprasidone and 82% of those on quetiapine. However, half of those who discontinued olanzapine did so because of weight gain or metabolic effects, compared to 18 to 25% of patients on other atypical agents and only 8% of patients on perphenazine. 30% of patients on olanzapine had a weight gain of ≥7% of their original weight vs. 7 to 16% of patients on other drugs. The mean increases in all the following parameters were greater for olanzapine than for other antipsychotics: blood glucose 15mg/dL (0.83 mmol/L) vs. 2.3 to 6.8mg/dL; Hb1Ac 0.41% vs. -0.1 to 0.1; total cholesterol 9.7mg/dL (0.25 mmol/L) vs. -9.2 to 5.3; and triglycerides 42.9mg/dL (0.48 mmol/L) vs. -2.6 to 19.2mg/dL. It was suggested that the doses of risperidone, quetiapine and ziprasidone used in this study may have been therapeutically suboptimal compared with olanzapine, with consequent minimisation of adverse effects. However, the results of CAFÉ, which compared olanzapine (using a smaller dosage range than in CATIE), risperidone and quetiapine in the treatment of early psychosis, confirmed the higher risk of metabolic adverse effects with olanzapine.7 The latest changes in US prescribing information Further changes to US prescribing information for olanzapine (but not for the other atypicals) were made in 2007 on the request of the FDA, to include additional information on the risks of hyperglycaemia, hyperlipidaemia and weight gain.8 The changes acknowledge the mounting evidence that atypical antipsychotics differ in the risks of inducing adverse metabolic effects.9 The prescribing information now states that "the association between atypical antipsychotics and increases in glucose levels appears to fall on a continuum, and olanzapine appears to have a greater association than some other atypical antipsychotics." There are also warnings of "significant, sometimes very high (>500 mg/dL) elevations in triglyceride levels" and "modest mean increases in total cholesterol". The prescribing information states that abnormal or borderline glucose levels at baseline are an important risk factor for further glucose increases. In a letter to health care professionals highlighting the changes, the company note that “changes in total and LDL cholesterol and triglycerides have been observed in patients with and without evidence of dyslipidaemia at baseline”.10 Legal challenges in the US Several US states are taking legal action against Lilly, accusing the company of concealing information about the association between Zyprexa (olanzapine) and weight gain and diabetes, and seeking reimbursement for Medicaid costs. In the first settlement, the company has agreed to pay $15 million to the state of Alaska without an admission of wrongdoing. It has been suggested that claims from other states could increase Lilly’s liability to over $1 billion. This is in addition to the $1.2 billion that the company has already set aside to settle around 30,000 individual claims.11 Changes in European prescribing information The European (and UK) Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) for Zyprexa was updated in 2001 to include a warning about hyperglycaemia and diabetes and the possible relationship to weight gain. The SmPCs for other atypical antipsychotics did not contain such a warning until some years later. In this respect, prescribing information in Europe has acknowledged for some time that adverse metabolic effects may be greater with olanzapine than with other agents. Following consideration of the current evidence by European regulatory authorities12, the SmPC for Zyprexa13 (but interestingly not yet for generic olanzapine products available in mainland Europe) was updated in January 2008 to include more detail on olanzapine’s effects on blood glucose and lipid levels and on weight gain. SmPCs for other atypicals have not been amended and it is unlikely that there will be an imperative for them to change in the near future. Is there any guidance on how this should affect practice? In considering olanzapine’s place in therapy and taking into account emerging information, the editorial that accompanied the publication of the CATIE study made several pertinent points.14 It stated that although olanzapine was the most effective drug in the study in terms of discontinuation rates, it was associated with notable metabolic effects which can affect cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. These may be considered to be more problematic than the side effect of tardive dyskinesia which has limited use of conventional antipsychotics. The editorial notes that because of the relative absence of side effects with risperidone, quetiapine and ziprasidone (the latter is not available in the UK) these agents are often used for the initial treatment of schizophrenia. However, it would seem reasonable to try olanzapine in patients who have not had a full clinical remission on these agents as it has been shown to have a striking effect on the course of the illness in some patients. The use of olanzapine must be a matter of clinical judgement and informed patient preference. Because of the metabolic problems that are likely to occur, dietary and exercise counselling should be given before the prescription. If metabolic side effects are threatening the patient’s health, treatment should be switched. NICE published guidance on the use of atypical antipsychotics in schizophrenia in 2002.15 It recommended that atypical antipsychotics are considered for the first-line treatment of patients with newly diagnosed schizophrenia and for those currently on conventional antipsychotics who are suffering unacceptable side-effects or who are in relapse and whose symptoms were previously inadequately controlled. There is no reference to the potential metabolic adverse effects of olanzapine. However, the NICE 2006 guideline for the management of bipolar disorder suggests a schedule of monitoring that implies a difference between atypical antipsychotics on blood glucose levels.16 The guidance recommends measuring blood glucose at the start of treatment, at three months and then annually for all antipsychotics; for olanzapine an additional measurement is recommended after one month of treatment. Recommendations for measuring weight and height (at the start and every three months for the first year - more frequently if the patient gains weight rapidly - and then annually) and for lipid profiling (at the start and at three months and then, in the over 40s only, annually) are the same for all atypical antipsychotics. The 2004 US consensus statement5 considers that the risks of obesity, diabetes and dyslipidemia have considerable clinical implications for patients “and should influence drug choice." It states that a careful risk-benefit analysis must be done for each patient before treatment is initiated. It recommends that the baseline risk for the development of metabolic adverse effects is assessed by taking a thorough personal and family history, and measuring the patient’s weight, height, waist circumference, blood pressure, fasting plasma-glucose level and fasting lipid profile. Appropriate treatment should be started if the patient is overweight, has hypertension, dyslipidaemia, hyperglycaemia or diabetes. The consensus statement suggests more frequent recording of body weight than NICE, at baseline, four, eight and 12 weeks and then quarterly. If a patient gains 5% or more of their initial weight while taking an antipsychotic, clinicians should consider gradually switching the patient to a medication with a lower risk of weight gain. A switch should also be considered if the patient develops worsening glucose or lipid levels. Subsequent to publication of CATIE and CAFÉ and the changes in prescribing information for olanzapine, the American Psychiatric Association has commissioned a review of the current evidence of metabolic effects with antipsychotic drugs. The review will provide updated clinical recommendations for screening, monitoring, and reducing cardiovascular and metabolic risks in patients treated with antipsychotic medications and should be available shortly.9 NICE is also updating its guideline on schizophrenia. It will cover the assessment and management of known side effects of antipsychotic medication, such as diabetes. Publication is expected in March 2009.17 References: 1. Newcomer JW. Antipsychotic medications: metabolic and cardiovascular risk. J Clin Psychiatry 2007: 68 [suppl 4]; 8-13 2. Anon. FDA’s proposed diabetes warning. Psychiatr News October 17, 2003: 38. Accessed via http://pn.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/38/20/26?maxtoshow=&HITS=10&hits=10&RESU LTFORMAT=&searchid=1&FIRSTINDEX=0&minscore=5000&resourcetype=HWCIT on 15/4/08 3. 2004 Safety Alert: Zyprexa (olanzapine). Accessed via http://www.fda.gov/medwatch/SAFETY/2004/zyprexa.htm on 15/4/08 4. Nasrallah, HA and Korn ML. Metabolic disorders in schizophrenia: relationship to atypical antipsychotic treatment. Medscape Psychiatry & Mental Health 2007: 9. Accessed via http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/483780 on 15/4/08 5. Anon. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004; 27: 596-601 6. Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 2005: 353: 1209-23 7. McEvoy JP, Lieberman JA, Perkins DO et al. Efficacy and tolerability of olanzapine, quetiapine and risperidone in the treatment of early psychosis: a randomised doubleblind 52-week comparison. Am J Psychiatr 2007: 164; 1050-60 8. Zyprexa. Prescribing Information. Eli Lilly & company. Revised March 2008. Accessed via http://pi.lilly.com/us/zyprexa-pi.pdf on 15/4/08 9. Yan J. Lilly agrees to Zyprexa labelling on glucose-metabolism risk. Psychiatr News November 16, 2007: 42; 5 Accessed via http://pn.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/42/22/5a?maxtoshow=&HITS=10&hits=10&RESULTFORMAT=&searchid=1&FIRSTINDEX=0&minsco re=5000&resourcetype=HWCIT on 15/4/08 10. Garnett T. Safety data on Zyprexa® (olanzapine) and Symbyax® (olanzapine and fluoxetine HCl capsules) – Hyperglycemia, Weight Gain, and Hyperlipidemia. Accessed via http://www.insidezyprexa.com/pdf/Dear_HCP_Letter.pdf on 15/4/08 11. Faigen N. Lilly to pay Alaska $15 million over Zyprexa data. Scrip 2 April 2008: p5 12. EMEA. Zyprexa. Procedural steps taken and scientific information after the authorisation. Accessed via http://www.emea.europa.eu/humandocs/PDFs/EPAR/Zyprexa/064696en8b.pdf on the 15/4/08 13. Zyprexa. Summary of Product Characteristics. Eli Lilly. Date of last revision January 2008 14. Freedman R. The choice of antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 2005: 353; 1286-8 15. National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Guidance on the use of newer (atypical) antipsychotic drugs for the treatment of schizophrenia. June 2002. Accessed via http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/ANTIPSYCHOTICfinalguidance.pdf on the 15/4/08 16. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Bipolar disorder. July 2006. Accessed via http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG38niceguideline.pdf on 15/4/08 17. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Scizophrenia (Update). Accessed via http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/index.jsp?action=byID&o=11657 on 8/5/08