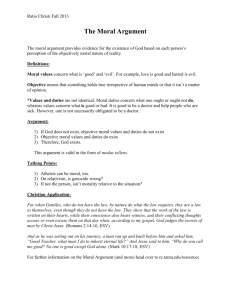

AS Religious Studies Revision Notes

advertisement