5.1.1 Strengthen existing customary forms of cooperation among

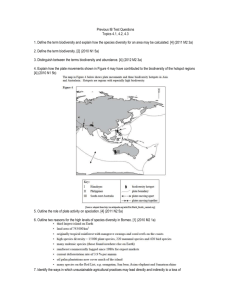

advertisement