Ten Tips for Successfully Responding to an OCR Investigation from

advertisement

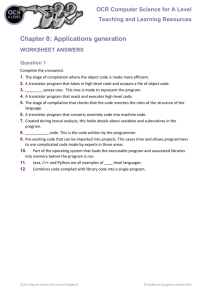

10 TIPS FOR SUCCESSFULLY RESPONDING TO AN OCR INVESTIGATION FROM START TO FINISH March 19 – 21, 2003 Cynthia Jewett Arizona State University Tempe, AZ Lisa Rutherford University of Wisconsin-Madison Madison, WI The mission of the Office for Civil Rights is to ensure the equal access to education and to promote educational excellence throughout the nation through vigorous enforcement of civil rights. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights “The Office for Civil Rights (OCR) enforces several Federal civil rights laws that prohibit discrimination in programs or activities that receive federal financial assistance from the Department of Education. These civil rights laws extend to all state education agencies, elementary and secondary school systems, colleges and universities, vocational schools, proprietary schools, state vocational rehabilitation agencies, libraries, and museums that receive U.S. Department of Education funds. Areas covered may include, but are not limited to: admissions, recruitment, financial aid, academic programs, student treatment and services, counseling and guidance, discipline, classroom assignment, grading, vocational education, recreation, physical education, athletics, housing and employment. “A complaint of discrimination can be filed by anyone who believes that an education institution that receives Federal financial assistance has discriminated against someone on the basis of race, color, national religion, sex, disability or age. The person or organization filing the complaint need not be a victim of the alleged discrimination but may complain on behalf of another person or group.” Excerpted from the Office for Civil Rights website (www.ed.gov/offices/OCR/aboutocr.html). I. THE SCOPE OF OCR’S AUTHORITY (AND LIMITATIONS ON AUTHORITY) In accordance with its mission, OCR is responsible for (1) preventive activities and (2) enforcement activities related to the following Federal civil rights laws that prohibit discrimination in programs or activities that receive federal financial assistance from the Department of Education: National Association of College and University Attorneys 1 A. Civil Rights Laws Applicable to Higher Education 1. Disability: Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act, 42 U.S.C. §12134 et seq.; 28 CFR Part 35 (35.190); ADA Accessibility Guidelines (“ADAAG”), 28 CFR Part 36 and Appendix to Part 36; Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, 29 U.S.C. §794; 34 CFR Part 104 (Subpart E, Postsecondary Education); 34 CFR 104.61 (Procedures); 2. Sex: Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, 20 U.S.C. §1681 et seq.; 34 CFR Part 106 (106.71 – Procedures); 3. Race/National Origin: Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C. §2000d and §2000d-1; 34 CFR Part 100 (100.6 through 100.11 – Procedures); and 4. Age: Age Discrimination Act of 1975, 42 U.S.C. §6103; 34 CFR Part 110. With the exception of allegations of age discrimination, complainants do not need to exhaust their administrative remedies before initiating litigation directly against the institution. As noted below, in 2000 only 1% of the complaints filed with OCR pertained to age discrimination allegations. Why is OCR such a busy federal agency? Recently, OCR observed that the coverage of these civil rights laws extends to “more than 4,000 colleges and universities” and to “nearly 15.4 million students attending colleges and universities.” Office for Civil Rights 2000 Annual Report to Congress. “During FY 2000, OCR received 4,897 and resolved 6,364 discrimination complaints, . . ..” Id. Of the complaints received in FY 2000, 25% (or 1224) were filed against postsecondary institutions (68% were against K-12 schools and 7 % were against vocational rehabilitation and other types of institutions). Id. The breakout of the complaints by civil right category was: 55% 18% 11% 8% 7% 1% Disability discrimination Race/National Origin discrimination Multiple grounds Sex discrimination Other (complaints outside of OCR’s jurisdiction) Age discrimination Organizational Structure of OCR OCR is a division of the US Department of Education. The reporting structure of the agency provides for 4 divisions (Eastern, Southern, Midwestern and Western) with each division having 3 regional offices. OCR has discontinued its former practice of referring to regional offices by number. 5. Eastern Boston (CO, ME, MA, NH, RI, VT) New York (NJ, NY, Puerto Rico, Virgin Islands) National Association of College and University Attorneys 2 Philadelphia (DE, MD, KY, PA, WV) 6. Southern Atlanta (AL, FL, GA, SC, TN) Dallas (AR, LA, MS, OK, TX) Washington, DC (NC, VA, Washington, DC) 7. Midwestern Chicago (IL, IN, MN, WI) Cleveland (MI, OH) Kansas City (IA, KA, MO, NB, ND, SD) 8. Western Denver (AZ, CO, MT, NM, UT and WY) San Francisco (CA) Seattle (AK, HA, ID, NV, OR, WA, American Samoa, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands) Preventive Activities of OCR A core responsibility of OCR is to develop and implement preventive activities to avoid discriminatory acts from occurring in the first instance. Examples of OCR’s efforts in Technical Assistance include: - Publications and guidances (e.g., OCR Case Resolution Manual, Guidances on topics such as disability harassment, disability – mitigating measures, sexual harassment, Brochures, such as “Students with Disabilities Preparing for Postsecondary Education: Know Your Rights and Responsibilities”) - On-site consultations - Co-sponsor or participation in conferences and workshops - Training Enforcement Activities of OCR The Office’s other core responsibility is to enforce the provisions of the federal civil rights laws under its jurisdiction. OCR achieves enforcement through several vehicles: 1. Compliance Reviews - OCR self-initiates these reviews. This flexibility allows the agency to pursue a concern when no formal complaint has been received and also allows the agency to make strategic use of its budgetary and manpower resources. If a violation of law if found, OCR will prepare a Corrective Action Agreement (CAA) with the institution which will detail the actions to be taken by the institution to remedy the violation. The CAA will specify the actions that are to be taken and the timeframes within which the actions are to be completed. OCR will then monitor the institution’s performance under the CAA. Per the 2000 Annual Report to Congress, OCR initiated 47 compliance reviews and closed 71 compliance reviews. The initiation of compliance reviews appears to National Association of College and University Attorneys 3 be decreasing – in 1999, OCR initiated 76 reviews, 102 reviews were initiated in 1998 and 152 reviews were initiated in 1997. Id. 2. Complaint Investigation and Resolution – OCR acts on receipt of a formal complaint. Complainant may be the alleged victim of discrimination or another person or organization may file on behalf of the victim. Outcomes that can flow from a complaint investigation are: a. b. c. d. Determination letter – issued when either complaint is not substantiated or OCR declines to investigate on any of the several grounds listed in the Case Resolution Manual (e.g., moot, withdrawn, litigation pending on same matter, allegations too convoluted). Resolution Between the Parties (RBP) – issued when the parties reach a mutual agreement between themselves without OCR making any findings of fact. Commitment to Resolve (CTR) – issued when OCR has determined that the institution is not in compliance with the law and the institution voluntarily agrees to take remedial action. OCR then monitors the CTR. Violation Letter of Findings (LOF) – issued when OCR has determined that the institution is not in compliance with the law and the institution is unwilling to enter into a CTR. OCR is limited to administrative action in this circumstance; OCR cannot institute litigation against college or university. Available sanctions: i. OCR may initiate administrative proceedings to terminate Department of Education financial assistance to the College or University, or ii. refer the matter to the US Department of Justice for the initiation of litigation to enforce any rights under the applicable civil rights law(s). OCR accomplishes resolution of concerns in large part by (a) serving as an impartial fact-finder who stops the assertion of baseless contentions within compressed timeframes, (b) raising the visibility of concerns to senior administrators (the notice of complaint letter is addressed to the President) who may not have been aware that a dispute existed but who can then direct appropriate actions to be taken to resolve the dispute, and (3) facilitating resolution at an early and low level to lessen the development of an adversarial relationship between the parties. II. AVOID A COMPLAINT OF DISCRIMINATION BEING MADE IN THE FIRST PLACE Are your existing policies and procedures consistent with the federal civil rights protections afforded to students at your institution? Consider conducting a legal audit of the policies and procedures adopted by your college or university: (a) to assess the need for and/or implementation process for reasonable accommodations and provide auxiliary aids and service to students with disabilities, (b) to administer the institution’s programs and activities without regard to sex, race, national origin, age or disability, and (c) to provide for an internal grievance process. Questions and situations will always arise, but the presence of existing policy and procedure will often serve to answer questions and end disagreements in the earliest of stages. National Association of College and University Attorneys 4 A. Institutional policies The development of appropriate policies, procedures and forms serves to educate the university community on the respective rights and responsibilities of students, faculty and administrators. The institution can establish reasonable standards and procedures for students to follow to obtain academic adjustments. University of Arizona, _ NDLR ¶ __ (Case No. 0902-2011 OCR 5/12/02), Temple University (PA), 8 NDLR ¶125 (OCR 1995), San Jose State University (CA), __ NDLR ¶ ___(Case No. 09-93-2161 OCR Region IX 1993)(university can require non-burdensome administrative tasks related to their accommodations be performed by the student). A student with a disability must exercise due diligence in seeking any requested academic adjustment. Id. (student failed to exercise due diligence in requesting adjustment of test taking conditions). Winona State University (MN), 22 NDLR ¶96 (OCR 2001)(no discrimination by university where neither student nor parents ever requested academic adjustments or services for the four courses that were the subject of the student’s complaint). The failure by a university to have appropriate policies in place to implement the protections of the ADA and Section 504 will be considered to be a violation by OCR. See e.g., Bellevue Community College (WA), 7 NDLR ¶135 (OCR 1995); United States International University (CA), 6 NDLR ¶206 (OCR 1994). References to university web pages for samples of policies and procedures pertaining to students with disabilities appear in the Appendix. B. Avoid Re-inventing the Wheel More than 4,000 post-secondary institutions in the United States receive federal financial assistance from the US Department of Education. The question or situation that is about to arise on your campus has likely already occurred at another college or university. Besides your institution’s existing policies and procedures, available resources that can be consulted include: 1. Other Institutions’ Policies – has another institution either developed a policy or successfully defended an existing policy that addresses an area for which your institution does not have a policy, but should? 2. Professional Associations - Higher education is fortunate to have numerous professional organizations that enable administrators to learn from one another’s experiences (e.g., NACUA, NCAA, SJAA, etc.). The sharing of day-to-day knowledge (e.g., NACUANET and its archive) as well as the continuing education materials developed by each professional group (NACUA conferences, NCAA Title IX compliance seminars, NACDA, SJAA conferences, International Study Program professionals) can provide helpful information. There are many questions and disputes that arise and are resolved at the institution level – without a complaint being filed with OCR or litigation being initiated. Professional colleagues can provide practical, effective advice. 3. Disability Specific Support Groups – there are extensive information resources available through the Internet that can provide basic background information on a particular disability or health condition. On occasion, you may find that a National Association of College and University Attorneys 5 student is providing information that is inconsistent with a particular medical condition or with an established practice. For example, when an employee began bringing a puppy to work, claiming that she was training the dog to become a service animal, the university was able to contact one of the established guide dog training schools to verify the process used for training guide dogs. The training group confirmed that the dog was too young to even start training. III. 4. Agency Website and Publications - consult the agency website to quickly access links to the applicable statutes, regulations, agency technical guidances, help lines, proposed regulations, press releases, agency procedures (e.g., OCR Case Resolution Manual). The URL for OCR is www.ed.gov/offices/ocr 5. Administrative Decisions – With decades of administrative enforcement of Section 504 since 1973 and now a decade of enforcement of Title II of the ADA, a substantial body of administrative decisions has developed. OCR has spoken on a broader range of disability issues than what can be found by surveying the reported court decisions. Accessing the administrative decisions can be accomplished through (a) making Freedom of Information Act requests to OCR, (b) consulting OCR and/or DOJ’s websites, or (c) subscribing to specialized news services, such as those offered through LRP, Inc. 6. Settlement Agreements - The text of actual settlement agreements is available at the US Department of Justice’s website: www.ada.gov The ability to access settlement agreements is helpful in advising your client on strategy if your institution finds itself on the wrong side of the law. 7. Reported Court Decisions - published decisions of the federal district courts and the federal circuit courts of appeals are available through the Internet as well as paid subscription services, such as Westlaw or Lexis/Nexis. Court decisions are also available on LRP’s “Disability Law on CD Rom.” LET’S START WITH SOME PROCEDURAL DEFENSES Because there is no exhaustion of administrative remedies requirement for disability, sex, race or national origin discrimination complaints, OCR has established a number of procedural grounds upon which it can decline to accept or pursue a complaint. OCR initiates a complaint on the information provided to the agency by the complainant. When your president receives notice of the complaint, you may possess additional facts that will enable OCR to drop the matter at the outset. A. What Constitutes a Complaint? OCR uses a complaint form (see Appendix). The agency does not consider: (1) oral allegations, (2) anonymous correspondence, (3) courtesy copies of correspondence or a complaint filed with others, or (4) inquiries that seek advice or information but that do not seek action or intervention from the department, to constitute complaints. OCR Case Resolution Manual at I.A. National Association of College and University Attorneys 6 B. Is the Complaint Timely? To be timely, all complaints of discrimination must be filed with an office of OCR within 180 days of the alleged discriminatory event.1 34 CFR §100.7(b). C. Is there a reason that makes OCR’s pursuit of the complaint unnecessary or duplicative? OCR may decline to pursue an investigation into complaint allegations because: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. The complaint is so weak, attenuated or insubstantial that it is without merit; The complaint is a continuation of a pattern of previously filed complaints involving the same or similar allegations against the same or similar recipients that has been found factually or legally insubstantial by OCR (Note: In 1999, one individual complainant filed 1,614 complaints with OCR per the 2000 Annual Report to Congress). The same allegations and issues of the complaint have been addressed in a recently resolved OCR complaint or compliance review. The complaint has been investigated by another agency and the resolution of the complaint meets OCR regulatory standards. The complaint allegations are foreclosed by previous decisions of the federal courts, Secretary of Education, the Civil Rights Reviewing Authority, or OCR policy determinations. The complainant withdraws his or her complaint. OCR obtains information at any time indicating that the allegations have been resolved. Litigation has been filed raising the same allegations. The same complaint allegations have been filed with another federal, state or local agency or through the recipient’s internal grievance procedures. OCR obtains information that the allegations are moot. The information received in the complaint does not provide sufficient detail to proceed with complaint resolution. Complainant refuses to cooperate with OCR. OCR transfers the complaint to another agency for investigation. Death of the complainant. See OCR Case Resolution Manual at I.H. for full description of the circumstances OCR will consider in deciding to decline further pursuit of a complaint. In two circumstances, OCR will not pursue a complaint investigation but may initiate a compliance review: 1. A complaint, because of its scope, requires a massive amount of resources, and 1 OCR may extend the time for filing in certain circumstances by allowing the complainant an opportunity to request a waiver. For a complete list of circumstances in which a waiver may be granted, please see the OCR Case Resolution Manual, I.G. The URL for the Manual is: www.ed.gov/offices/OCR/docs/ocrdrm.html National Association of College and University Attorneys 7 2. IV. Multiple individual complaints against the same recipient are received. THE ART OF THE PRE-EMPTIVE STRIKE There is no reason your college or university should always be in the position of last to know or always having to respond to an allegation(s) that has been framed by a complainant. In many instances it pays to get out in front of a situation. A. Use OCR’s Legal Staff As noted above, OCR is responsible to implement preventive action and to this end, its staff is there to answer questions and give guidance to its constituents. If your institution is encountering a novel situation, consider calling an OCR staff attorney to get an informal opinion. The benefits of this action can include: 1. helping to establish and/or maintain a professional rapport with the staff attorneys; 2. gaining credibility for the institution for taking steps to educate itself to comply with the civil rights laws; 3. while you will likely only receive an informal (and verbal) opinion, if a dissatisfied student later brings a challenge and your institution followed the informal opinion, the likelihood of a determination favorable to the institution increases; 4. if the staff attorney disagrees with the institution’s proposed course of action, you’ve gained the opportunity to debate the issue more thoroughly in a nonenforcement context. You may succeed in convincing the attorney to your view or you’re better informed about the counter-arguments and can further analyze the weight they should receive. In the alternate, you’ve gained the opportunity to alter the institution’s course of action and thus avoid a subsequent complaint by the dissatisfied student. The drawbacks: 1. your question may draw greater attention to the issue by the agency than the situation would have otherwise drawn; 2. you may get an answer you don’t like or are not able to implement. Weigh the risks – consider who will make the call on behalf of the institution and who, at OCR, is to be contacted. Outline your points, authorities and carefully frame the question. ASU followed this approach when we were confronted with the request by a deaf student to provide a sign language interpreter for a full academic year of study abroad in Ireland. The student then filed a complaint with OCR over the university’s denial of the request. OCR issued its determination letter, upholding the University’s decision. Arizona State University, 22 NDLR ¶ 239, No. 08012047 (OCR Denver 2001). National Association of College and University Attorneys 8 B. Use OCR’s Publications and/or “Blessing” of Institutional Publications As part of its prevention activities, OCR offers numerous publications to help explain the respective rights of students and educational institutions. A familiarity with the publications list will enable you to refer students and/or their parents to a particular publication to head off a complaint being made to OCR. For example, one issue that has been arising with greater frequency on university campuses is the situation of the newly enrolled college student who has grown up receiving services under the Individuals with Disabilities in Education Act (“IDEA”) and believes that the college or university must provide the same level of services at the post-secondary level under either Title II of the ADA or Section 504. To reduce the number of complaints in this area, OCR released a new pamphlet in July 2002 entitled “Students with Disabilities Preparing for Postsecondary Education: Know Your Rights and Responsibilities.” This document is available on-line or as a printed pamphlet. The routine provision of this document to new or prospective students by your institution’s Office of Disability Resources may stop many disagreements from ever arising. An institution may agree to develop a policy or an institutional publication in the course of resolving a student complaint filed with OCR. OCR reviews and approves the policy or publication. If subsequent questions or disagreements arise between the institution and a student and/or parent, the institution can speak from a position of strength in saying that the particular document has been reviewed and approved by OCR. At ASU, our briefing paper “Educating Students with Disabilities at the Post-Secondary Education Level” (see Appendix) was developed in this manner and has been effectively used many times with students, parents, faculty and staff to resolve contrasting opinions without OCR needing to become involved. C. Calling the Bluff: Give the Dissatisfied Student the Telephone Number to Your Regional OCR Office or Call OCR Yourself On occasion, students registering for service with the Office of Disability Resources make unreasonable demands for accommodations or auxiliary aids and services. The student, through sheer force of personality, may have succeeded in getting a prior institution to accede to the same or similar demands. In these situations, consider whether a university staff member should call OCR or whether you think allowing the student to speak for himself or herself would better convey to OCR the inappropriateness of the demand (see Section II.C, above). Either way, there is great benefit to neutralizing the threat of “I’m going to file a complaint with OCR” at the start of the institution’s relationship with the student. V. A COMPLAINT OF UNLAWFUL DISCRIMINATION AGAINST YOUR INSTITUTION HAS BEEN FILED WITH OCR: STRATEGIES FOR A SUCCESSFUL INVESTIGATION Should a complaint with OCR be filed against your institution, the following outline provides practical considerations for planning your strategy in each stage of the process. As with any complaint, knowledge is key to a successful defense. In the early stages, it is important to gather together internal and external information. Because OCR provides an institution only the very minimum of specifics regarding a complaint, the following actions are recommended: National Association of College and University Attorneys 9 A. Understand OCR’s Perspective of Time Constraints OCR is charged with reaching a determination on a complaint of discrimination within 180 days of its receipt of the complaint. 34 CFR §110.39 and OCR Case Resolution Manual, II.B. By the time you are having your first conversation with the investigator and first opportunity to obtain the factual substance behind the general allegation stated in the notice of complaint letter, perhaps as much as 30 days has passed since the complaint was received by OCR. The investigator may offer you a fairly short period of time within which to respond (i.e., next day responses as contrasted to the OCR Case Resolution Manual’s provision that at least 15 calendar days should be provided). Prompt responses to OCR requests can be beneficial, particularly if they cut off the need for a more detailed investigation. This is particularly the case where the complaint is straightforward and easily addressed through existing written documentation. However, some complaints raise complex and/or subjective issues requiring careful investigation and analysis. Counsel should be prepared to argue for a reasonable length of time within which the institution will respond. Undue or unnecessary delays in responding to OCR should be avoided, if at all possible. Note: OCR staff receives incentive pay if they close 80% of their cases within 180 days from the receipt of the complaint. B. Begin a Dialog with OCR On the day the complaint comes down to your office from the president’s office, call OCR to inform them which attorney in your office will be handling the complaint and ask which investigator is assigned to handle the case. Call them that day or in the early stages of an investigation, contact the OCR investigator and discuss the complaint. An early contact has several important purposes: 1. OCR staffs a complaint investigation by utilizing a “work team” approach that consists, at minimum, of a supervisory team leader, a staff attorney and an investigator. The investigator is not an attorney. The investigator is going to be your point of contact person. 2. Establishes a rapport with the investigator. This cannot be stressed enough—the investigator will review all of the information provided to the OCR and, in all likelihood, conduct the on-site investigation. An amicable relationship with the investigator may prove invaluable should an investigation later expose an institutional problem that needs correcting. 3. Allows the investigator to provide guidance. In conducting an investigation into the complaint, it is important to understand OCR’s understanding of the complaint. 4. May prevent frequent follow up. It is possible OCR may want specific information from the institution. Providing that with a written response may prevent having to do numerous follow up responses to OCR requests for information. National Association of College and University Attorneys 10 C. Use the Freedom of Information Act OCR protects the privacy of individuals who file complaints. Unless agreed upon in writing, OCR will not disclose the complainant’s name. As a result, a typical notice from OCR of a complaint filed against an institution includes only a very brief summary of the allegation(s). The following examples are the entirety of the complaint allegations provided by OCR to an institution: “The Complainant alleges that the University discriminated against persons with disabilities by failing to provide an appropriate number of spaces for persons who use wheelchairs at Camp Randall Stadium.” “OCR received a complaint filed by Student A against UW-Madison alleging that the university discriminated against Student A on the basis of disability by (1) refusing to follow its usual practice of assisting UW-Milwaukee students in obtaining a field placement in Madison and (2) requiring Student A to release information on Student A’s disability to potential placement sites.” “The complaint alleges that the University submits students to harassment based upon race.” Although it may be possible to respond to the specific complaint, the context in which it was made may be helpful in planning a defense. For additional information, an institution may request the complaint and supporting documentation from OCR by using the Freedom of Information Act. 34 CFR Part 5. D. Understand the Culture of Department/Unit 1. Determine the rationale behind the decision To evaluate credibility and appropriateness of a departmental response to a situation, it is imperative to understand why a certain action was taken. Ask: “Has it always been done this way?” “Is there a reason it is done this way—i.e. accreditation requires it; rules permit it; academic standards and program integrity require it; it’s consistent with our technical standards.” “Have there ever been exceptions?” “Why and under what circumstances?” OCR will question the reasoning behind the decision to determine if an action was justified and will uphold an institution’s right to establish and maintain legitimate nondiscriminatory policies, standards, etc. See Letter to Quinsigamond College, No. 01-94-2060 (OCR Boston 1994) in which OCR concluded the College’s attendance policy and requirement for hands-on experience were not discriminatory. See Board of Education of the City of New York, 12 NDLR ¶157, No. 02-97-1125 (OCR New York 1997) in which OCR upheld dismissal of a mobility-impaired student who could not fulfill all of the clinical requirements of a nursing program. National Association of College and University Attorneys 11 See Letter to Florida Community College, 21 NDLR ¶192, No. 04002062 (OCR Atlanta 9/12/00) in which OCR upheld the College’s requirement that a student meet a specific diploma requirement for admission despite the student already possessing an “exceptional student program” diploma. 2. Visit the Scene Attempt to put yourself into the environment about which the complaint was made. If it is an accessibility complaint under Title II of the ADA, view the structural barrier; if it is a climate issue, spend time in the department/unit during the regular course of business. Doing so assists with making a credibility determination of both the complainant and the department. Furthermore, viewing the scene will assist in the determining whether OCR should tour it during an on-site visit. E. Collect general as well as specific facts OCR will contact an institution in response to a specific complaint. However, in resolving the complaint, OCR may make conclusions and expect resolution of issues that go beyond the complaint. For example, an individual may complain that a denial of his accommodation request was a violation of the ADA. In making a determination, OCR will conclude if an institution followed its accommodation process with respect to the individual as well as make a determination about the legality of the accommodation process in general. 34 CFR §100.7(c) (“The investigation should include, where appropriate, a review of the pertinent practices and policies of the recipient, the circumstances under which the possible noncompliance with this part occurred, and other factors relevant to a determination as to whether the recipient has failed to comply with this part.”) See Letter to New Mexico Highlands University, No. 08002045 (OCR 10/13/00) in which an individual claimed portions of a university building were not accessible. OCR conducted a barrier access review of the entire building. See Santa Clara University, No. 09-00-2108 (OCR, Western Division, San Francisco Regional Office, 2001) in which OCR reviewed the method by which the university addressed complaints about failure to accommodate even though the specific complaint filed with the OCR was time barred. See Appendix, for a resolution agreement sent to the University of Wisconsin-Madison in response to a complaint filed solely about the number of wheelchair accessible seats in the stadium. The agreement included accessibility issues for public restrooms, telephones, etc. VI. REMOTE INVESTIGATIONS: RESPONDING TO THE CHARGE WHEN OCR CONDUCTS THE INVESTIGATION FROM ITS OFFICE In many instances, OCR is going to conduct its complaint investigation from its offices and will not come on-site. That is, the exchange of information will occur through the use of correspondence, faxes, e-mails and telephone calls. When responding to an OCR complaint investigation that is conducted in this manner, it remains important to provide all relevant information and supporting documentation. National Association of College and University Attorneys 12 A. OCR is entitled to all information and documentation 34 CFR §100.6(c): Each recipient [of federal funds] shall permit access by the responsible Department official...during normal business hours to such of its books, records, accounts and other sources of information, and its facilities as may be pertinent to ascertain compliance…. 2 At the outset, find all policies and procedures that apply to the complaint situation. This includes policies at your board of trustees/regents level, university level, college level and school or department level. Make sure you’ve got the edition of the policy and/or procedure that was in effect at the time the alleged wrongful conduct occurred. Determine if the policies and procedures were followed by the complainant AND the department/unit. OCR reviews policies and makes determinations based upon them. See University of California, Davis, 4 NDLR ¶108, No. 09-92-2101-I (OCR San Francisco 1993) in which OCR concluded University’s policy of suspending interpreter services because of no-shows to class or late cancellation was permissible. But see, reported settlement of federal class action lawsuit with UC Davis (Siddiqi v. Regents) wherein university agreed to abolish its policy that a hearing-impaired student’s interpreter would leave class if the student did not show up within the first 10 minutes of class and the interpreter would not continue reporting to class if the hearing-impaired student was more than 10 minutes late on three occasions. Chronicle of Higher Education, November 12, 2002. See University of Wisconsin-Madison, No.05-00-2033 (OCR Chicago 7/27/00) in which OCR upheld the University’s denial of an accommodation when individual making the request failed to follow proper procedure. The importance of documentation when responding to an OCR complaint cannot be overstated. Under the broad grant of power contained in 34 CFR §100.6, OCR investigators are to have access to documentation within the custody of the institution. OCR uses documentation to (a) corroborate oral statements, (b) develop interview questions of witnesses, (c) establish the factual record and (d) support its investigative findings. OCR Case Resolution Manual, Tab B. 1. This includes providing student records without written consent: 34 CFR § 99.31 (a)(3)(ii): An educational agency or institution may disclose personally identifiable information from an education record of a student without the consent required by §99.30 if the disclosure…is subject to the 2 Interestingly, there is no corresponding authority to OCR to require the complainant to provide supporting documentation. In practical effect, if a complainant does not cooperate with requests from OCR the agency may decline to pursue the investigation any further. National Association of College and University Attorneys 13 requirements of §99.35, to authorized representatives of the Attorney General of the United States. 2. If voluminous, it is acceptable to give OCR direct access. OCR Case Resolution Manual, Tab B III.C.3: If a recipient invites OCR to come on-site and collect the requested information, and provides OCR with sufficient access to files, records, logs and appropriate indexes for OCR to extract the needed information, then the recipient has provided OCR with the requisite access. 3. Confidentiality protections permitted OCR Case Resolution Manual, Tab B III.D: To protect the confidential nature of the records, OCR may permit the recipient to code names and retain a key to the code. However, if such a procedure impedes the timely investigation of a case, OCR will access unmodified records. 4. Don’t Just Think 8 ½ x 11 Paper In addition to correspondence, forms, policies and procedures, catalogs, medical documentation, handwritten notes, cards, transcripts, and codes, relevant documentation can be in the form of: e-mail, web pages, and other electronic data, microfilm and microfiche, ads, blueprints, photographs, diagrams, CAD drawings, etc. B. Gather Names and Follow Through with Interviews of Witnesses OCR may rely on university counsel to list the individuals who are the most knowledge of a situation. To make this determination, anyone with relevant information should be interviewed. This allows for the collection of background information, sorting out relevant information, determining the quality of the witnesses and preparing individuals for a possible interview by an OCR investigator. This will enable you to prepare a factually accurate written response to the discrimination complaint, even if OCR makes no request for interviews. If the OCR investigator does wish to interview witnesses, he or she should send a written notice to you with the request that each scheduled witness be provided with a copy of the notice before a substantive interview starts. OCR Case Resolution Manual, Tab B.IV. A copy of the standard notice forms can be found in the Appendix. OCR investigators are to document each interview and this can be done by either keeping hand-written notes of the interview or by tape recording. If the OCR investigator wishes to tape record, the witness must consent to such taping. Id. Ask the investigator when the issue of interviewing witnesses first arises if legal counsel will be permitted to sit in on the in-person interview or be on the telephonic interview. C. Disclose the Successes and the Failures 1. Admit the Failure and Provide a Plan to Remedy National Association of College and University Attorneys 14 If, during the course of an investigation, a problem is discovered, this should be revealed to the OCR. Along with the disclosure, provide a plan to remedy the situation. For example, if a bathroom does not comply with Title II of the ADA, admit it to OCR and provide details of the remodeling plan, including blueprints, anticipated construction dates, bills paid to date, etc. A proactive response may prevent further OCR investigation and/or an on-site visit. See Felician College, No. 02-00-2131 (OCR, Eastern Division, New York, 3/09/01), in which a student complained that certain buildings did not provide wheelchair access. OCR found validity to some of the student’s complaints but, because the College had either completed corrections or was in the process of making the necessary corrections, concluded the complaint was resolved. 2. Accentuate the Successes It is equally important to share the “good” with OCR. This may take a variety of forms. For example, in response to a Title II ADA complaint in which the university is not currently in compliance, provide OCR with information about completed renovations addressing a different Title II issue. Likewise, provide details on any current construction or renovation projects and how Title II issues are addressed. For a Title IX complaint, provide newspaper clippings of awards, honors and accomplishments of female student athlete teams, players and coaches. By highlighting proactive activities or, as with Title IX, celebrating the accomplishments of a particular population, OCR may be more inclined to provide the institution with greater latitude in resolving the current situation. See Notre Dame College, No. 01-01-2002 (OCR, Eastern Division, New Hampshire, 04/24/01) in which the OCR approved a five-year renovation project to provide accessibility. National Association of College and University Attorneys 15 D. The Town/Gown Aspect of OCR Investigations Some types of disability discrimination complaints lend themselves to matters that are beyond the strict control of the college or university. For example, many college and university campuses are large enough that they are either intersected and/or bounded by city streets. While many institutions maintain their own sworn police departments, they receive fire and emergency medical services from the city. If the institution receives notice of a complaint challenging the sufficiency/safety of accessible routes or emergency evacuation procedures, the institution may need to seek input from city officials to support the rationale of prior administrative decisions. This collaborative input may be obtained through specifically scheduled meetings or through a standing committee with membership from both the institution and the city. For example, the Public Safety Advisory Committee at ASU is a standing advisory committee to the Executive Vice President for Administration and Finance. City fire, police and public works representatives participate with university representatives from police, risk management, parking, media, general counsel, staff, faculty and student councils. See Arizona State University (AZ), 15 NDLR ¶187, No. 08-98-2064 (OCR Denver 1998), in which a student complained that the university failed to provide her with an accessible route across a street that bypasses the campus. Student also alleged that students with disabilities were treated differently than students without disabilities since the university provided a safer alternative (a pedestrian bridge) to crossing the street to students without disabilities. OCR held for the university, finding that 4 crosswalks that complied with ADA accessibility guidelines were provided. Also, university had engaged in a process with the city to develop additional safety measures. The “pedestrian bridge” was constructed prior to 1977 for the primary purpose of running utility lines, not for pedestrian use. See Arizona State University, No. 08022020 (OCR Denver 2002), in which a class action complaint alleged that the university’s emergency evacuation procedures discriminated against students with disabilities residing in the university’s residence halls. OCR held for the university, finding that the emergency evacuation plan adopted by the university was effective for students with disabilities. Prior to the complaint being filed with OCR, this issue had been publicly debated on campus. The attendance and participation of the city fire chief was critical to explaining the safety concerns with the proposals made by the students with disabilities while explaining the safety concerns that were met by the existing university policy. The fact of the fire department’s participation and the content of its professional recommendations were documented in the minutes of the Public Safety Advisory Committee and became a key exhibit for the university. VII. ON-SITE INVESTIGATIONS: PREPARING FOR AND HOSTING AN OCR INVESTIGATION OCR may choose to inform an institution that it is coming on campus to speak with witnesses, review documentation, inspect buildings and conduct its own inquiry in response to the complaint. An on-site visit is more likely where (a) the complaint is directed towards accessibility/structural barrier issues or (b) OCR is undertaking a compliance review under Title IX of the institution’s intercollegiate athletics program. An on-site visit also may be likely in other complaint contexts when your institution is located in close geographical proximity to an OCR regional office. A well-presented onNational Association of College and University Attorneys 16 site visit can be an institution’s best defense to a complaint of discrimination. In addition to the points mentioned for remote investigations (section VI, above), consider the following: A. Preparation 1. Witnesses As with litigation, a well-prepared witness is an absolute must. Regardless of the amount of information that university counsel may have previously provided to OCR up to this point, the witnesses will be the key to the final outcome. If possible, choose the witnesses for the investigator. However, be prepared for the investigator to request speaking with additional witnesses as the investigation progresses (the complainant may suggest individuals to the investigator). In preparing your witnesses, consider the following: a. Witnesses should be encouraged to talk freely and openly. Advising a witness to answer every question to the extent possible aids institutional credibility and, ultimately, advances the institutional position. b. Witnesses should know what policies/procedures and other documents have been provided to OCR and freely refer to that documentary record, as appropriate. i. 2. Witnesses should be prepared to educate the investigator. The investigator may be well versed in the law but have limited knowledge of how it applies to an institutional specific situation. For example, an investigator expected UW-Madison to add a new women’s sport within three months to comply with the substantial proportionality component of Title IX. Logistically, adding a sport in a short time frame was impossible. Strategically Choose an Interview Site If possible, conduct the interviews where the investigator will get the best understanding of the institutional rationale behind a decision. This can be done by (1) providing the investigator with a tour of where an incident took place or a decision was made and (2) arranging for the interviewer to spend some time in a unit by conducting the investigation in the heart of the action. For example, in a complaint of discrimination alleged by a medical resident, the interviews were held in a conference room in the hospital near the patient examining rooms. During the course of the interviews, medical personnel and patients could be seen moving through the hallways and the overhead paging system was audible. The activity underscored the university’s position that a resident needs to be a team player in a fast paced, close quarter environment. National Association of College and University Attorneys 17 3. Environment OCR is coming to your institution. Assess if experiencing the environment/culture advances the institutional position. Does the investigator need to “get a feel” for an environment to better understand the rationale behind a decision? Spend some time at the site to prepare yourself in advance for what the investigator will see during a visit. As you prepare directions for the investigator, consider what the investigator will see as he or she walks on your campus. (Realize, however, that the investigator can, and will, walk additional and/or alternate routes while on campus. Get out and have a sense of what is happening on your campus so that any potential problem areas can be inquired into and not leave you surprised.) B. Hosting the Investigation 1. Hospitality is Important C. a. An investigator expects an institution to arrange a productive visit. Take the initiative and prepare an agenda in advance of the investigator’s arrival. List the individuals with whom the investigator will meet, providing name and title. Share the draft agenda with the investigator. He or she can make revisions but will appreciate your efforts to make the visit productive. Be prepared to schedule appointments between the investigator and each witness. Leave extra time for additional interviews in anticipation of the investigator adding witnesses as the investigation progresses. The agenda can serve as a quick check sheet for the investigator to refer to and helps to keep all parties on a schedule. Have documents ready or know where to find them. Consider finding a space for the investigator to work between interviews and tours. b. A working lunch can be productive in terms of efficient use of the investigator’s time and to establish a rapport in a neutral location. An establishment on campus saves travel time, allows the investigator to get a sense of the campus and also provides food at a reasonable cost. The OCR investigator will not allow his or her lunch to be paid for by the institutional representative. On-Site Investigation of Accessibility Complaints Prior to the arrival of OCR, it is critical for institutional representatives to conduct a pre-inspection to determine the strengths and weaknesses of the building or other structure that is the subject of the pending complaint. This inspection should help you identify obvious and not so obvious relevant documents that you will want to have readily available when OCR is on-site. In addition, the pre-inspection can assist in identifying the areas of expertise relevant to the complaint. Those individuals need to be prepared and present. Be prepared for the complainant to join you in the on-site visit. He or she may be accompanied by an attorney or National Association of College and University Attorneys 18 advocate. Be prepared to set the ground rules if the entourage is not limited to institutional representatives and OCR. 1. ADAAG: Have your own copy of the ADA Accessibility Guidelines because everyone else (i.e., OCR and the complainant) will most certainly have their copy (highlighted and dog-eared). Prior to OCR arriving on-site, make certain you have determined which accessibility standard your institution chose to for the newly constructed or altered facilities – ADAAG or Uniform Federal Accessibility Standards (UFAS). See University of California, Berkeley, 25 NDLR ¶16 (OCR San Francisco 2002) in which student complained that university’s athletic facility did not fully comply with accessible seating guidelines for patrons in wheelchairs and did not provide appropriate accessible emergency evacuation procedures. OCR agreed with complainant but considered the matter resolved because the university planned to modify the seating arrangements and evacuation procedures. 2. Applicable Codes: Know the history of the building and have identified and copied the sections of the applicable codes that were in force at the time of construction or modification (e.g., building codes, plumbing codes, electrical codes, fire codes, etc.). You may also want current code sections available as well. 3. Know Your Property Lines: Complainants will judge a college or university by its physical appearance and draw conclusions as to roads, sidewalks, parking lots, or buildings being “university property.” In many instances, the legal description of the property shows otherwise. Always verify that the structural barrier being complained about is your institution’s responsibility. If it is not, then promptly advise OCR so they can close the complaint as to your institution or redirect the complaint or a portion of it to the US Department of Justice for enforcement action. 4. Yard Stick, Tape Measure, Camera: Come equipped with the tools that are appropriate to respond to the complaint against the institution. Again, OCR will have their tools in hand. Caveat: strict dimensional compliance may not be sufficient if the overall design of the area renders it inaccessible. For example, a dorm room might have the proper minimum dimensions, but if the design is poor such that closet or cabinet doors cannot be opened, then you’ve likely still got a problem. Involvement of your institution’s Accessibility Coordinator at the planning stage of construction projects is essential. 5. Subject Matter Experts: Your institution’s ADA Accessibility Coordinator is a key person to have at any accessibility inspection. Other personnel will vary, but may include, architects, engineers, fire marshals, project managers, parking director, athletics personnel responsible for the stadium or arena, etc. National Association of College and University Attorneys 19 6. D. Budget Authorizers: Prior to proposing any remedial action to OCR or agreeing to an action proposed by OCR, it is important to understand the technical steps that will need to be taken, the length of time to accomplish the work, the cost of the remedial work, and the budget resources that are available to pay the cost. Once an agreement is reached, it is difficult, if not awkward, to attempt to go back and revisit the commitment. On-Site Investigation of Title IX Compliance of Athletics The decision by OCR to conduct a compliance review of your institution’s athletics program under Title IX will almost certainly involve an on-site visit to your campus. The President will receive a notice letter describing the scope of the compliance review that will be undertaken (i.e., assessment of written policies/procedures, a tour of the institution’s athletic and ancillary facilities, and interviews with coaches, student-athletes, athletic directors, and other persons responsible for administering the university’s athletics program). The university will be required to provide relevant documentation to OCR in advance of the on-site visit. Typically, OCR will attach to the notice letter a list of all document categories that are to be supplied with a specified deadline. The notice letter will also identify a tentative visit date (could be week-long) when the inspectors will be on your campus. The scope of the compliance review can be expected to cover the “laundry list” of program components: 1. the provision of reasonable opportunities for award of athletic financial assistance (34 CFR §106.37(c)); 2. the selection of sports and levels of competition equally effectively accommodates the interests and abilities of members of both sexes (34 CFR §106.41(c)(1)); 3. whether the institution is providing equal opportunity for male and female athletes under the following factors addressed at 34 CFR §106.41(c)(2)-(10): i. ii. iii. iv. v. vi. vii. viii. ix. x. xi. the provision of equipment and supplies (c)(2); scheduling of games and practice time (c)(3); travel and per diem allowance (c)(4); opportunity to receive coaching and academic tutoring (c)(5); assignment and compensation of coaches and tutors (c)(6); provision of locker rooms, practice and competitive facilities (c)(7); provision of medical and training facilities and services (c)(8); provision of housing and dining facilities and services (c)(9) publicity (c)(10) support services (added through 12/11/79 Policy Interpretation) recruitment of student-athletes (same) The compliance review is to be completed by OCR within an established target date (typically 120 days after the commencement of its site visit). A Corrective Action Agreement addressing each program component that is not in compliance with the law will be prepared. See Appendix for a copy of the initial notice letter and resulting Corrective Action Agreement for National Association of College and University Attorneys 20 Arizona State University. ASU is going into its tenth year of monitoring under the CAA, as we remain out of compliance on the issue of substantial proportionality with the question of financial assistance deferred until substantial proportionality is achieved. Counsel should be monitoring the activities of the federal panel on Title IX. Good resources include the websites maintained by the US Department of Education (www.ed.gov) and the Chronicle for Higher Education (http://chronicle.com/daily). The Panel’s final report is due to the Secretary of Education by the end of February 2003. The report’s recommendations will not be binding on the Secretary. VIII. NEGOTIATING AND STANDING FIRM A. Think Global In resolving the complaint, an institution may be agreeing on how to act in all future similar circumstances. Before resolving the complaint, consider if it is realistic or desirable to deal with similar situations in the same manner. B. Know When to Say “NO” Remember that you know your institution better than the investigator. Determine if a resolution proposed by OCR is in the institution’s best interests. In deciding on whether to accept resolution conditions offered by OCR, consider the following: 1. Reasonableness of OCR’s position to the institution Although an OCR investigator may be an expert in the law, he/she is not necessarily well versed in how it applies to a specific situation. During the course of a Title IX investigation, OCR concluded that UW-Madison would be in compliance if it reinstated a female varsity sport in 4 weeks and added a new sport within 3 months. Both expectations were unreasonable given the logistics of creating and managing an athletic team at the Division I level. To counter these unreasonable expectations, your institution should be prepared to layout, through written documentation (a) the budget cycle of your institution, (b) the full cycle of steps to start up a sport, (c) a breakdown of all the costs associated with starting up and operating the specific sport, (d) the relevant cycle for scheduling of athletic contests, etc. These various forms of documents serve to establish the reasonableness of the length of time being proposed by the institution for the seamless incorporation of a new sport such that the other existing sports programs are not unduly disrupted. 2. Going Over the Investigator’s Head The investigator assigned to your case is NOT a lawyer. He or she may be new to OCR, may have never handled the particular type of complaint that is at issue National Association of College and University Attorneys 21 on your campus, or may just not “get it.” He or she may be checking with the team leader, who may not be an attorney either. When you are not able to agree to a term proposed by OCR and you’ve got solid legal and/or factual arguments, call the OCR staff attorney directly to press your argument. Consider also putting your argument in writing. The written record is crucial in terms of making sure your argument is not misreported as the various levels of agency review take place. 3. Prior OCR findings Before standing firm, it is recommended to research other OCR findings in similar circumstances. The OCR does not appear to set nation wide standards for all types of complaints such that regional offices may make different findings on similar fact patterns. In Title IX substantial proportionality cases, the Chicago office appeared to expect a ratio of less than 3% even though the Denver office allowed a 5% differential. 4. Research Tools The following resources can provide valuable comparative information as to the terms under which other similar complaints have been resolved. i. ii. iii. Freedom of Information Act requests may be made to the Washington, D.C. office.3 34 CFR Part 5 (Note: Department of Education is to maintain current indexes providing identifying information for the public as to any matter – opinions, orders, statements of policy and interpretations, administrative staff manuals and instructions to staff, see 34 CFR §5.13(b)); Search the web: www.ada.gov is the web site maintained by the US Department of Justice. Settlement Agreements are posted to this site on a periodic basis. If you have an accessibility dispute, in particular, this website can provide insight into tolerances for agreed upon time frames for implementing alterations. See if your local law library subscribes any of LRP’s publications on disability law. “Disability Law on CD Rom” is issued monthly and includes statutes, regulations, administrative decisions and court decisions on Titles I, II and III of the ADA and §504 of the Rehabilitation Act. “Disability Compliance for Higher Education” is a monthly newsletter that covers disability issues at colleges and universities and provides summaries of case decisions and OCR administrative decisions. “Disability Compliance Bulletin” is a monthly newsletter that covers Titles I, II and III of the ADA and §504 of the 3 The number of FOIA requests made to the U.S. Department of Education has been decreasing with the placement of agency material on its website and those of its various offices, including OCR. OCR determination letters and orders are not routinely placed on the web. National Association of College and University Attorneys 22 iv. v. C. Rehabilitation Act. Coverage does include college and university matters but it is not limited to higher education. Post a NACUANET inquiry. It is not a level playing field when all is said and done. OCR maintains an intranet so that its staff members can access all determination letters, commitments to resolve, resolutions by parties, and settlement agreements pertaining to all areas under its jurisdiction. Unlike disability discrimination claims, where an institution can subscribe to an LRP subscription service, there is no equivalent for discrimination complaints based on sex, age, race or national origin. LRP does offer a newsletter on Title IX, but its contents are limited to athletics arena (“Title IX Compliance Bulletin for College Athletics”). Understand the Process for Challenging Decisions If the investigator and the institution are unable to reach a voluntary resolution, the investigator will initiate an enforcement action by sending the case to administrative proceedings to terminate financial assistance or by referring the case to DOJ for judicial proceedings. Before taking either step, the investigator will issue a Letter of Finding in which OCR states its conclusions and explains the consequences of failure to achieve a voluntary resolution. OCR Case Resolution Manual, III.A. Importantly, before the Department of Education terminates any funding, an institution will be provided a right to a hearing. Furthermore, any termination of funding will be limited to the particular program in which noncompliance has been found. 34 CFR §100.8(c). The administrative hearing process is laid out in 34 CFR §§100.8 - 100.11. IX. Commitments to Resolve The strategy for developing a Resolution Between the Parties and/or a Commitment to Resolve is similar to that used in any litigation settlement agreement. The primary difference, however, is that a Commitment to Resolve almost always will contain a monitoring component such that the “settlement” does not officially close a complaint. A well-fashioned Commitment to Resolve is a useful tool and a productive resolution. A. Positive Considerations 1. Halts Investigative Process If an institution agrees to resolve a complaint through a settlement process, OCR will not conduct any additional investigation. If the decision to enter into a Commitment is made early in the process, it may prevent OCR from recounting detailed information in its summary. See Letter to Augustana College, No. 07-00-2069 (OCR Kansas City, 9/27/00) in which the College entered into a Commitment to Resolve early into the process avoiding OCR providing specific facts in its cover letter or Commitment. National Association of College and University Attorneys 23 See Letter to the University of Southern California, No. 09-99-2112 (OCR San Francisco 12/29/99) in which USC entered into a resolution commitment without admitting any wrongdoing. See Lincoln Land Community College, No. 05-01-2008 (OCR Midwestern Division, Chicago Office 2/01/01) in which the college and student entered into a commitment to resolve regarding the issue of auxiliary aids in a timely fashion. By entering into the commitment at an early point in the process, OCR closed the investigation without a complete investigation into the complaint. 2. Avoids a negative finding For a complaint in which OCR probably will conclude a legal violation has occurred, it makes sense for the institution to enter into a Commitment to Resolve on all or a portion of the complaint. By resolving the institution’s weaker points early on, the university indirectly turns the investigator’s attention to the aspects of the complaint more favorable to the institution. See Letter to Notre Dame College (NH), 20 NDLR ¶29, No. 01-00-2053 (OCR Boston 9/6/00) in which Notre Dame acknowledged a deficiency in appropriate signage for the visually impaired and entering into a Commitment to Resolve on that point but prevailed on the remaining aspects of a complaint filed on behalf of students with visual impairments. B. Negative Considerations 1. Monitoring Requirement Entering into a Commitment to Resolve will not officially close a complaint. All Commitments will include a monitoring component in which the OCR sets time lines within which the institution is to act.4 OCR will strictly observe those time lines and, if an institution fails to act without reasonable explanation, may reopen the investigation, issue a letter of findings and/or forward the complaint on for enforcement action. 2. Negotiating Acceptable Terms Because OCR may not have a good understanding of the practicality of a solution for a particular institution, it may be difficult to reach mutually acceptable terms. Typically, OCR expects a quick implementation of a plan or a 4 From the OCR Case Resolution Manual, II.G: All agreements should be crafted with a view toward effective monitoring. Any agreement must incorporate the following...(a) specific acts or steps the recipient will take to resolve allegations; (b) the timetable for implementing each act or step; and (c) a specific timetable for submission of documentation. National Association of College and University Attorneys 24 change in policy. Oftentimes, for an institution to change a policy or process, it may require committees to redraft it and legislative bodies to vote on it. Be cautious in negotiating away typical institutional time frames. If the institution cannot meet the expectations of OCR, it may be better not to negotiate a resolution. X. CONCLUSION The majority of discrimination complaints investigated by OCR pertain to disability issues: academic adjustments as well as accessibility issues. The ever-growing body of case law and administrative decisional law provide guidance on a variety of issues. The precedents enable both OCR and universities to answer compliance questions fairly early in the life of a complaint. Prompt resolution of disability complaints also benefits from the existence of policies/procedures (and other written documentation) and/or precise, objective measurements that come from ADAAG or applicable local codes. A cooperative approach to uncovering the relevant facts and evidence tends to be highly effective on these types of investigations. Similarly, complaints under Title IX concerning college athletics are measured against a “laundry list” of components set forth in the regulations (34 CFR §106.41(c)). Every institution with an intercollegiate athletics program will have an extensive amount of documentation relating to all aspects of its sports programs (e.g., Equity in Athletics Disclosure Act (EADA), records kept per the requirements of NCAA legislation, student records, budgetary records of the department, etc.) The development of a collaborative and collegial working relationship with OCR on Title IX complaints is advisable because literally every institution that receives an OCR visit will find themselves entering into either a Corrective Action Agreement (CAA) or Commitment to Resolve (CTR), either of which will include a monitoring component. On-going monitoring can last years and years, such that it is not unusual to encounter “changed circumstances” (e.g., change in athletic director, institution’s president, local economy, etc.). It will be to your institution’s benefit in seeking an amendment to the CAA or CTR if a collegial rapport has been built and maintained with the agency. Specific complaints based on sex, age, race or national origin discrimination are relatively rare. Conducting an intensive factual investigation is essential to determine if a violation of law has occurred. These matters should be handled with full awareness that litigation could subsequently be filed. The complainant, through his or her attorney, may be seeking some free discovery. In this circumstance, a formal and professional relationship with OCR is advisable. In summary, consider the following 10 tips when your institution is confronted with an OCR investigation: 1. Call OCR the day the notice of complaint is received to introduce yourself as the university attorney assigned to the matter and to obtain the name and phone number of the OCR investigator. Get as much factual background to the complaint as you can over the phone so you can promptly start your investigation. 2. Make a FOIA request for the actual complaint and supporting documentation if the OCR investigator will not reveal factual information beyond the written notice of complaint. National Association of College and University Attorneys 25 3. Establish a rapport with the OCR investigator. Even if the determination is made in a particular case to adopt a more formal, arms-length relationship with OCR, it is essential to maintain a professional and collegial manner of communication with the agency. 4. The OCR investigator is not an attorney. Find out from the investigator who else is on the work team, including the staff attorney. When warranted, don’t hesitate to go over the investigator’s head to the staff attorney. 5. Learn the culture of the college or university unit from which the complaint arises so that you have the proper context against which to identify relevant witnesses and make credibility determinations, understand why practices or procedures have been adopted, and the circumstances under which exceptions to practice or procedure have been or will be made. 6. Conduct a broad fact-finding inquiry. While OCR will be investigating the specific complaint of the student, the agency will also be considering the overall adequacy of your institution’s policy(ies) and procedure(s). If the complaint concerns a structural barrier, OCR will look at the entire building/parking lot/common area, etc. 7. Be prepared to provide or allow inspection of all relevant documentation. OCR has broad inspection powers. Think beyond 8 ½ x 11 paper when searching for information that is relevant to the investigation. Good documentation will end an investigation quickly and will generally result in a finding favorable to the institution. 8. Disclose all relevant information, the good as well as the bad. Self-identify appropriate remedial actions, if a problem is discovered. Initiate negotiations for either a Resolution Between the Parties or a Commitment-to-Resolve to avoid OCR making adverse findings of fact. 9. Keep in control of on-site investigations through planning and preparation: prepare an agenda in advance, identify relevant documents and subject matter experts to participate in the visit, anticipate the possible attendance by the complainant and set ground rules, and encourage the investigator to experience the institutional environment. 10. Keep your promises. Virtually any form of agreement with OCR has a monitoring component. Throughout the negotiation process it is essential to involve knowledgeable institutional representatives who can identify: (a) internal procedures/committees that may be impacted, (b) practical constraints that will impact the timeline for accomplishing an end result, (c) budgetary cycles and resources, and (d) the senior level administrator who will have to agree to the terms and sign the agreement on behalf of the institution. National Association of College and University Attorneys 26