The Maximization of Falsifiability: How the Child realizes the logic

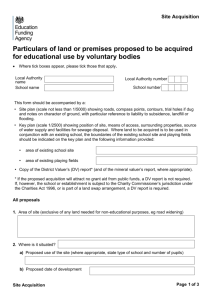

advertisement

The Maximization of Falsifiability: How To Acquire the Logic of Implicatures from The Illogic of Experience Tom Roeper UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS 1.0 Introduction to an Intricate Interface Deductive reasoning requires precision in the definitions of logical words.The word “logic” itself refers to that notion, although in daily life the term“ logical”, like virtually all words, is used with pragmatic ambiguity and even wilful imprecision. The pragmatic force of real life situations is very important when one addresses the acquisition question: how does a child’s innate knowledge mesh with experience in order to lead to the understanding of particular grammars. The discussion to follow originates in elementary reasoning about how we should conceive of the acquisition path. It does not reflect a thorough background in philosophy, logic, the evidence of how implicatures work, nor a thorough study of adult uses of logical terms, nor a much-needed careful study of how children use logical terms in naturalistic contexts beyond experimental contexts. An acute application of what is already known will, one hopes, enhance the claims to follow, but may challenge them as well. This discussion should be seen as a prolegomena to the study of these questions, and a plea for pursuing one angle on that interdisciplinary research.1 Learnability theory needs to be conceived of with sufficient intricacy and sensitivity to meet the actual kinds of variation that children experience every day. The argument below is that the concept of Maximization of Falsifiability (MaxF) is ideally suited to the task. This paper follows the theory of Anna Verbuk: that MaxF can apply to the interface between pragmatics and semantics. I will present and expand upon a few of the core examples in her work and seek to orient it in a larger context. Where do the complexities of real life entangle the acquisition process? One place is the difficult dividing line between pragmatics and semantics (Levinson (2000)). For instance, as we shall see, while some unusual properties of quantifiers might simply be considered forms of “pragmatic strengthening ” for adults and therefore irrelevant to the core definition of logical terms, it may not be immediately evident to the child that a property of pragmatics is not a property of the semantics and therefore required in any exercise of deductive logic, independent of context. The claim here is that a child’s apparent errors may reveal more strict deductive reasoning than adult’s reasoning precisely because their definitions of crucial terms may, briefly, carry stronger restrictions. It appears that languages vary in what information is included in quantificational terms. Terms in Dutch like “allemall” vary across the meaning “often” “all the time” and “all kinds”.2 Terms like “all the time” in English can mean either constantly or repeatedly. Acquisition of such terms requires a lot of subtle work by children and a capacity to register the nuances of triggering experiences. 1.1 Maximization of Falsifiability Edwin Williams (1981) advanced an important idea for learnability theory: the Maximization of Falsifiability (MaxF). The claim is that: (1) a. A child’s initial representations (definitions) of words and nodes are as rich as possible. (1) a. A child’s initial representations (definitions) of words and nodes are as rich as possible. Definitions which are too broad are compatible with too many interpretations, while highly specific definitions are quickly contradicted by experience. In a word, vague or incomplete representations are the enemy of learning. The impact of negative information, which can change grammar, is strongest when the definition of words are too precise and restrictive., which we will illustrate shortly. In that sense, this theory adheres to the logic of the Subset principle at the semantic level. (See Berwick (1985), Crain and Thornton(1998)). New information expands the number of sentences that the grammar accommodates by reducing grammatical restrictions, which in turn gradually makes the rules more abstract. Here is a little illustration of how it can work, and how quickly it can work. Suppose the child hears either den (German) or the in front of a noun. Let the child guess that it is an article. How should she determine its properties. Suppose in both cases the child makes the Maximal assumption about possible features associated with articles (probably there are more than these in fact) (2) a. English Child I saw the man Masc Sing Accusative Definite b. German child: Ich sah den Mann Masc Sing Accusative Definite The German child will be immediately right. The English child quite wrong, but the Hypothesis lends itself to contradiction. In five minutes the child might hear “I saw the woman” which cancels the gender feature, then “I saw the girls” which cancels the singular feature, and then “The girls came” which cancels the accusative feature leaving only definiteness. There is no reason not to believe that a great deal of micro-acquisition occurs—within a few hours---much like many steps in the mastery of bicycle balance occur in the few minutes after a child manages to stay on a bike. If the opposite strategy is assumed— the/den = only definiteness--then the English child will be right, but the German child will freely use den in nominative positions and with plurals, etc. What will force a change. Hearing Der (nominative) Mann is a nominative form, but also carries demonstrative force, and therefore it might not be seen as an alternative blocking the use of den. The child could easily continue with the assumption that either der mann or den Mann is acceptable. The conditions for revision are far more obscure if one seeks to add features. It is interesting to ask how far MaxF can be applied. Not only syntax but implicatures, as we will show, and also, following Verbuk and Roeper (2006) the acquisition of Principle B in binding theory can be understood from this perspective. Nevertheless, the concept of Maximization of Falsifiability itself is an idealization that is surely too strong. There must be contexts where a child does add to the definition of words as well as subtract from them and at least a few contexts where acquisition depends upon comparison of words and an application of the “uniqueness” assumption that words have different meanings. 1.2 Innate Logic A strong and important claim has been advanced by Cherchia (2004): in essence, the principles of logic are innate and therefore a) require no learning, and b) instantly engender implicatures which are implicitly or explicitly computed all of the time. Acquisition evidence (Papafragou (2006) and, Guasti et al (2004) , and others) have suggested that the implicature consequences of these principles by children are not immediately realized. Therefore it could be that the entire capacity for computing implicatures must be triggered or mature, or become available via an interface computation (see Reinhard (to appear), although mixed evidence leaves such a conclusion rather murky. Others (Papafragou and Tanatalou (2004), Papafragou (2006)) have claimed that the implicatures involving “world knowledge” are particularized in a way that slows their acquisition. Horn (2005) argues that pragmatics is present everywhere. We will argue that the range of possible definitions of words with logical force within Universal Grammar is much larger than usually supposed. Consequently the task of isolating the logical force of words is not straightforward and requires subtle, and pragmatically exact experiences. Nevertheless deductive reasoning must eventually be possible---even against pragmatics---and it supplies us with the capacity to, for instance, build a theory of linguistics where grammaticality can be identified without the requirement of compatibility with context. The argument here is that the child must, in some domains, move from a restrictive pragmatic definition to a broader semantic one. It could be an implicit goal of growth, belonging to the whole species, to find definitions that allow strict deductive reasoning free of pragmatic qualifications. To put it differently, the efficiency of language in general lies largely in guaranteeing meanings that are independent of context and which can even support antipragmatic readings (see Hollebrandse and Roeper (to appear)). Sentences like: (3) John met every person in the world have a meaning which is impossible. but its meaning is computed as fast as any other sentence---as well as its implausibility, without any particular context needed. 1.3 Inference and Implicature Horn (2005) and Papafregou (2006) argue and provide evidence that children can undertake particularized situational implicatures. We argue that some of these implicatures belong to General Inference which is needed to see what is not said, to infer motives, in every conversation, and in many non-verbal situations. They should be kept distinct from implicatures that are properties of words which are immune to pragmatic modification. General inference, while deep and complex, computes plausible, not implausible consequences of situations. In contrast, a statement like the following has a logical implicature whether we can make sense of it or not: (4) Some people are people. implies automatically that Not all people are people, a conclusion with which we have to struggle cognitively, using any kind of inference, including a strong sense of irony or cynicism, to rescue from apparent nonsense. Nevertheless the implicature is present. While it might seem counter-intuitive at first, it is really quite plausible to argue that children bring enormous inferential capacities to the earliest stages of acquisition. In effect, when a sentence is not understood, one tries to make inferences from individual words to possible meanings. This occurs at the one-word stage. Every utterance requires an interpretation for why it is said. The interpretive demand is greater if your grammar is smaller. The child who hears: “Milk!” must be able to translate it into a range of meanings like “do you want some milk” or “be careful and don’t knock over the milk carton” using a lot of inferential power. 2.0 Projecting Restrictors It is a fundamental feature of quantification that it carries both overt and covert restrictors: (5) every child must wear a bathing suit The quantifier every (Heim (1988)) is restricted by the noun child and by some property of the context, such as, in this class. Now we can ask: what constitutes a possible restrictor and how far does it get built into the quantifier itself. Here is where one can be unsure of what is entailed. Elementary time and location restrictions appear to be present without much contextual demands: (6) the boy wearing a red shirt stole the fruit yesterday. This sentence can mean a boy wearing the red shirt now or a boy wearing a red shirt during the robbery. A kind of optional default restriction to Here and Now seems to be present in many circumstances. Are there others? Piaget originally proposed that children cognitively presupposed “simultaneity” in various tasks, but Schmiedtova (2004) has shown that young children have the capacity to make the distinction between what is simultaneous and what is not. We argue that the phenomenon is not a cognitive unit but a part of the system whereby implicatures are calculated. It fits the MaxF systematic effort by children to over-restrict meanings in order to ultimately isolate the correct meaning. Apparent misapplication of simultaneity could be seeking an implicature where none is present, although perhsps it sometimes is. Consider this case: (7) Here are 500 bricks. Can you lift all of them? The natural answer is “no, they would be too heavy”. But note that there is an implication of “all at once” that is not logically necessary. Surely one could lift them one by one. Many situations are open to an ambiguity here: (8) a. Could you carry all your toys to your room? This could mean all separately or all at once. Anna Verbuk reports (to appear) that children often reveal their restrictions in overt conversation. One 4.11 yr old child was asked if one animal had scratched all of another’s body and responded (“a card” means “no”), (8) b. A. (4;11): A card. Because he didn’t do it all at once. Cause he (=Tiger) was asking him (=Deer) to do it (=scratch Tiger’s body) all at once, even though he didn’t say, “do it all at once Many others offer similarly complex reasoning. From the perspective we are pursuing, the child is doing precisely the correct thing: he is maximizing the possible features associated semantically with “all”. The adult, by contrast, has this meaning as an implicature, a part of Pragmatic Strengthening if the context calls for it. It is not a part of the meaning of all when we engage in deductive reasoning. Could this meaning enter the logic of how quantifiers are interpreted elsewhere? Papafragou and Tantalou (2006) gave children sentences involving some whose implicature should be not all. They were given a scene of this general kind: (9) 1. First two animals jump over the fence 2. Then another animal jumps over a fence 3. Then a third animal jumps over a fence When 6 year-olds were asked: (10) “Did some of the animals jump over the fence” they answered “yes” while adults answered “No”. This has been taken to mean that the children have not been able to process the implicature. However they are surely aware that all the animals have jumped over the fence and this implicature is far less complicated than many inferences that are implicitly made by toddlers. If however children have applied the logic of MaxF to some as well as all, then we make precisely the correct prediction about the children’s “yes” answer as seeking a restrictor that allows “yes”: (11) Did some of the animals jump over the fence at once? Put in as a restrictor it would be: (12) Did “some at once” of the animals jump over the fence? If this logic holds for a wide variety of implicatures, then we will expect the process to involve a great deal of quite specific experience. There are interesting examples that suggest that children might entertain quite unusual restrictors that apply in the domain of comparatives as well. Consider this dialogue from the Adam Files of Childes: (13) Ursula: its much bigger Adam: it’s much smaller too Ursula: it’s much smaller! how can it be both! Such forms of differentiation are not unknown in the adult language, but there is a default notion that bigger/smaller applies to the whole object. If the tail were bigger and the head were smaller we might say “one is both bigger and smaller than the other” with the implication to search for restrictions that would render the sentence non-contradictory. Now let us imagine what the range of possible restrictors could be for one quantifier: all. Then we will provide the kinds of experience which force the child to drop those excessive restrictors. 2.1 Kinds of All The following are examples of possible extensions of the meaning of all: 1. Kind: all = all kinds a. we have all Toyotas on our lot. 2. Variety: all = any possible selection a. we have all nationalities at Umass. 3. Collective: all = group action a. we all lifted the table 4. Exclusive: all = all and only (possible, but not English) a. he picked up all the toys. 5. Adverbial: all = completely a. he ran all the way around the house 6. Adverbial: all = isolated (?) a. he sat all by himself. 7. Quotation: all = enthusiastic attribution a. he was all “I can do it” All of these example sentences are not far removed from the language of parents to children. It would be useful to do a study and see exactly which ones occur. The common property of all is assumed to be exhaustivity. Is this property reliably honored? Consider a situation like this: (14) [5 of 50 students are present at the start of class] Someone says with disdain: “all the students come late to this class” If a child hears some version of this sentence, spoken with common exaggeration, he is entitled to assume: all = most. This would be a difficult assumption to overturn since in every situation where all is used, it would also be true of most. How can we block such a modification? A careful look at the concept of restrictor suggests that it must indeed restrict. Suppose we tried to add a restrictor of the general form roughly speaking—to capture moments of casual overstatement--- to any quantifier. This move would render the quantifier vague in a way that most conceivable evidence could not rescue. By our logic, it would make language unlearnable. Therefore the possible restrictors must themselves be constrained. To state it informally: restrictors must restrict and not expand the relevant domain. It is quite possible that there is a further range of restrictors that apply which we have not seen and which, being short-lived, do not exhibit themselves overtly in the acquisition process. 2.2 Triggering Progress Children have many informative experiences. The child who might briefly entertain the idea that all = most would surely have some corrective experience, which imposes exhaustivity: (15) [two of twenty toys are not picked up by a child] “you didn’t pick up all your toys Similarly if the child assumed, which does not seem unnatural, that all = all and only, experiences would arise, where one says: (16)a. [person buys food and clothing] “I bought all the food” b. [adult reads a series of stories] “ I read all the stories” where the reading for (16a) “all and only” is therefore ruled out and for (16b) the reading “all at once”. A great deal of learning via the MaxF principle would be accomplished silently (see Verbuk for discussion). It might be quite unclear 90% of the time that a child is using a more restricted form of the quantifier all. 3.0 The Path across Quantifiers Are there implications here for the path of quantifier acquisition as a whole? One of the most startling facts is the wide disparity in the appearance of quantifiers. While their frequency is not equal, they all appear far more often than many other nouns and verbs that children readily acquire. Therefore any delay needs an explanation. While 2 yr olds use all easily, it has been found that every is very rarely used (deVilliers and Merchant (2006), Roeper et al (2006)). Only 18 instances of every+N were found among 10 children and they appeared between 4-5 years. As is well-known children make errors in the comprehension of “spreading” as well, allowing an object to treated exhaustively as well as a subject (every cowboy is riding a horse = every horse is being ridden by a cowboy). How does the child learn that all can have a collective reading but it is rare for every and excluded for each. Imagine this contextual contrast: (17) Imagine: set of balls and bats ball ball ball ball ball ball ball bat bat bat bat bat bat bat And now the instruction: (18) “Point to all the balls” => child points to the whole row (19) Now imagine this interchange: “Point to every ball” Child points to the whole row. which elicits this Negative Trigger: (20) “you didn’t point to every ball” Such an experience is not implausible, but it might be that one could only be sure that an experience of that kind occurred over the course of several years, unlike the the/der learning procedure above. Is there any mechanism that could make the process more efficient. It is possible that the set of quantifiers are learned in a partly paradigmatic fashion: blocking a restrictor on one becomes a block for all. There is a range of options that the child seeks to capture, involving contrasts in collectivity, proportion (most, few), and other factors that interact with the notion of set. It would radically enhance acquisition efficiency if the child eliminates a restrictor for the entire set at once, moving a semantic property by MaxF into the pragmatic domain. Further evidence might be needed to make individual quantifiers exceptions to the set. 4.0 Maximization of Falsifiability Elsewhere: Or, And, Reflexives, and Binding Theory These subtle ambiguities are not isolated. We find that words like and, or, then have special features as well. Thus if we say John ate meat ‘n rice or John ate meat and rice the former more naturally associates with eating them together or “at once”. Bryant (2006) has in fact shown that children may overapply the notion of simultaneity in contexts where and occurs with gapping in German sentences roughly like (the elephant brushes the lion, and the dinosaur __ the cat [= dinosaur brushes the cat]). Adults do the two actions separately while children struggle to do them at once. Or allows both an inclusive and exclusive reading. For instance, you can’t eat a hamburger or a lemonade allows the reading that you can have lemonade in Russian. Verbuk has shown that children initially give a default wide-scope to the negative in Russian, blocking that reading, and Goro and Crain (2004) have made extensive studies along the same lines in several languages. Reflexives show the same kind of interesting ambiguity. In English the expressions: (21) a. John and Mary kissed themselves b. John and Mary kissed have different meanings. In (21a) each person only kisses him or herself. In (21b) it is a joint activity (See Roeper and Roeper (2005) for a game theory account, see also Rubinstein (2006)). If the joint activity is chosen as the Default restriction, then evidence of distributivity will occur for the reflexive, dropping the “joint” restroction, but never occur for the empty object (21b). In German the monomorphemic reflexive sich captures the joint reading and the complex form sich selbst captures the distributive reading. Iumguelzow and Roeper (in preparation) show that children do not immediately choose the right meaning for each type of reflexive. Similarly Verbuk and Roeper (2006) argue that children must exclude a range of possible additional restrictions for reflexives like John hurt himself, for instance physical, intentional, and subtle aspects of perspective (see Levinson (2000)) before its parametric opposition to the form him can be realized. 5.0 Conclusion The emergence of implicatures, both conventional and conversational, following the logic of MaxF in Verbuk (to appear) requires us to imagine a very subtle process whereby semantic and pragmatic factors are differentiated. This argument applies the classic logic of learnability to the learnability of logic. The child must have a method to discard potential pragmatic restrictions on logical terms in order to isolate their logical force. Only then does one generate an implicature for words like some to the effect that it entails not all. Or that all operates without a time restriction and therefore does not mean “all at once”. The differentiated meaning under MaxF will encounter sharp contrary evidence, either quickly or only when special circumstances arise, that block the assumption that a circumstantial restrictor belongs to the inherent eaning of the word. This predicts that each logical and quantificational term (e.g. all, every, each) will have its own acquisition path. This claim receives strong, straightforward evidence from the naturalistic data. Several years separate the emergence of words like all from the emergence of every. The role of subtle triggering experience here needs to be kept clearly in mind. If one takes a general approach, it may appear that children need a frequent exposure to certain words in order to learn them. This is true as a first order empirical generalization, but it does not mean that frequency itself can be the source of discrimination. If certain crucial environments for learning are quite rare, then it may appear that greater frequency is needed when in fact what one needs is more instructive experiences. Second language acquisition instruction reflects this reality. Anyone who has learned a second language, remembers environments where words seem to be used in a surprising way when we thought we knew what they meant. Those are the moments from which we learn, not from a statistical representation of how often the word has occurred. Teachers, likewise, will often compare two situations to explain how two similar words differ. In sum, we have argued that issues at the interface between syntax, semantics, and pragmatics require the same kind of learnability logic that has been advocated for syntax alone. In fact, the diversity of information that contributes to various possible restrictors makes the need for efficient and constraining mechanisms to guarantee acquisition success increasingly necessary. Notes Thanks particularly to Anna Verbuk for discussions. Chris Potts and Uli Sauerland made helpful remarks in various conversations, as did the audiences at the ZAS conference on intersentential anaphora, Tokyo Psycholinguistics Conference, and Tohuku University 2 For instance, Hollebrandse (2006) have interesting evidence that Dutch children are misled by precisely this range of ambiguities. 1 References Berwick, R. (1985) The Acquisition of Syntactic Knowledge MIT Press Bryant, D. (2006) Koordinationsellipsen im Spracherwerb: Die Verarbeitung potentieller Gapping-Strukturen. Akademie Verlag. (Studia grammatica 64) Berlin: Chierchia, G. (2004). Scalar Implicatures, Polarity Phenomena, and the Syntax/Pragmatics Interface. In A. Belletti (ed.), Structures and Beyond. Oxford University Press, Oxford. Crain, S. and R. Thornton(1998) Investigations in Universal Grammar MIT Press deVilliers, J. and G. Merchant (2006) “Children’s Use of the Quantifier “every” Current Issues in First Language Acquisition Umass Occasional Papers in Linguistics 34 ed. Tanya Heizmann Guasti, M. T., Chierchia, G., Crain, S., Foppolo, F., Gualmini, A., Meroni, L. (2005).Why Children Sometimes (but not Always) Compute Implicatures. Language and Cognitive Processes. 20 (5): 667-696. Goro, T., Minai, U., & Crain, S. (2004). Two disjunctions for the price of only one Proceedings of the 29th Boston University Child Language Heim, I. (1988)) The Semantics of Definite and Indefinite Noun Phrases. New York: Garland Horn, L. (2005). The Border Wars: a Neo-Gricean Perspective. In K. Turner & K. von Heusinger (eds.), Where Semantics Meets Pragmatics. Elsevier. Hollebrandse, B. (to appear). “Topichood and quantification in L1 Dutch”. To appear in International Research in Applied Linguistics 42. Iumguelzow,I. and T. Roeper (in preparation) Children’s Acquisition of Reciprocals and Distributivity Levinson, S. (2000). Presumptive Meanings: The Theory of Generalized Conversational Implicature. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Papafragou, A., & Tantalou, N. (2004). Children's computation of implicatures. Language Acquisition 12: 71-82. Papafragou, A. (2006). From Scalar Semantics to Implicature: Children’s Interpretation of Aspectuals. Journal of Child Language 33: 721-757. Reinhard, T. (to appear) “The Processing of Reference Set Computation: Acquisition of Stress-shift and Focus” NYU ms. Roeper, T. U. Strauss, and B. Pearson “The Acquisition Path of the Determiner Quantifier Every: Two Kinds of Spreading” Current Issues in First Language Acquisition Umass Occasional Papers in Linguistics 34 ed. Tanya Heizmann Roeper, T. and T. Roeper (2005) “Game Theory and Syntactic Control” Paper Presented at ZAS Conference on Game Theory Rubinstein, A. (2006) “An investigation of the denotations of reciprocal verbs and the semantic foundations in which they are grounded” Umass ms. Schmiedtov, B. (2004) At the same Time...The Expression of Simultaneity in Learner Varieties Studies on Language Acquisition 26 Verbuk, A. and T. Roeper (2006) “The Acquisition of Principle B” Umass ms. Verbuk, A. (to appear) Acquisition of Scalar Implicatures Umass Dissertation Williams, E. (1981) "X-bar Theory and Acquisition" in S. Tavakolian Language Acquisition and Linguistic Theory (roeper@linguist.umass.edu)