Ascites

advertisement

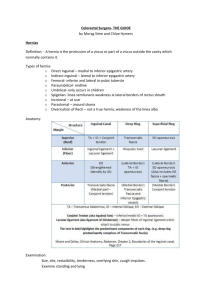

Embryology and Normal Ultrasonographic Appearance of the gastrointestinal canal The embryonic gut has three major parts: the foregut (esophagus, stomach, proximal duodenum, liver, and pancreas), the midgut (distal duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and proximal colon), and the hindgut (distal colon, rectum, anus, and parts of the vagina and bladder). Dilation of the foregut during the 6th menstrual week leads to the formation of the stomach, which then descends into the abdominal cavity by the 8th to 9th week. The midgut typically returns to the abdominal cavity by the 11th week. Although intestinal peristalsis begins by week 11, it can rarely be visualized ultrasonographically before the second trimester. Fetal swallowing is evident before the end of the first trimester, and beyond the 14th week, the stomach should be visualized in nearly all normal fetuses. With a transvaginal probe, the stomach can be visualized as early as the 9th week of gestation. In contrast, the normal fetal esophagus is not generally visualized ultrasonographically. The small bowel and large bowel can be imaged and distinguished from each other, particularly in the third trimester. The more centrally located small bowel is often difficult to discern in normal fetuses, appearing as a relatively homogeneous, slightly echogenic mass. The small bowel remains more echogenic than the large bowel until near term, displaying active peristalsis during the third trimester. Late in the third trimester, small bowel loops are commonly identified, generally measuring less than 15 mm in length and rarely more than 5 mm in diameter. Improvements in ultrasound imaging technology have permitted the imaging of small bowel loops as early as 14 week's gestation. The colon frames the fetal abdomen, appearing as a continuous tube with a hypoechoic lumen. Meconium creates this hypoechoic appearance, in contrast to the echogenic bowel wall. In fact, normal colon with liquid meconium is often mistaken for pathology (eg, dilated bowel, cysts). The colon exhibits far less peristalsis than the small intestine. By the middle of the third trimester, colonic haustra can be identified in nearly all fetuses, despite the fact that clinically, haustra are generally poorly developed in newborns. The diameter of the large bowel increases in linear fashion from 3 to 5 mm at 20 week's gestation to up to 20 mm at term. Although colonic grading has been attempted based on comparative echogenicity, the clinical utility of this approach has not been demonstrated. The liver is the dominant organ in the upper fetal abdomen, the area for standard abdominal circumference measuremen. The gallbladder is often overlooked or misrepresented ultrasonographically (under the assumption that it represents an intrahepatic vein). Although it is a sonolucent structure, its ovoid or conical shape and lack of flow on color Doppler or power angiography, as well as its location inferior and to the right of the intrahepatic segment of the umbilical vein, should help distinguish it The spleen is another upper abdominal organ that is often overlooked or mistaken for an abnormal solid left-sided mass. Although not always easily visualized, it can usually be seen throughout the second half of gestation, posterior to the stomach and lateral and superior to the left kidney. It is homogeneous in appearance and slightly less echogenic than the liver, similar to the kidney. The pancreas is sometimes visualized in the third trimester as well, especially with the fetus in a supine position. ABSENT STOMACH Inability to visualize the stomach in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy requires further examination. Repeated examination over time (several hours or days later) confirms a normal fetal stomach in about half of cases. Esophageal atresia should always be considered when polyhydramnios is accompanied by failure to visualize the stomach bubble. The differential diagnosis for this problem is summarized in the table. Differential Diagnosis of Absent Stomach Bubble Empty stomach (time) Esophageal atresia with or without tracheoesophageal fistula Diagphragmatic hernia Situs inversus Oligohydramnios Facial clefts Central nervous system disorders ESOPHAGEAL ATRESIA Esophageal atresia should always be considered when polyhydramnios is accompanied by failure to visualize the stomach bubble. However, 90% of cases are associated with a communicating tracheoesophageal fistula, usually with a visible stomach. The gastric mucosa alone may produce enough fluid to allow visualization of the stomach in some cases of atresia without fistula. The blind pouch of the proximal esophageal segment has been seen infrequently, as has regurgitation after fetal swallowing during real-time observations. Associated anomalies are seen in nearly 60% of cases, with other gastrointestinal (28%), cardiac (24%), and chromosomal (19%) anomalies being the most common. As with most intestinal atresias, esophageal atresia is rarely diagnosed before the third trimester. Although the survival rate is particularly poor overall (less than 50%), the prognosis is much improved with isolated esophageal atresia (85% survival rate). DUODENAL ATRESIA Duodenal atresia, with an incidence of about 1 in 5000 births, is the most common intestinal obstruction encountered in the perinatal period. The lesion is most commonly caused by one or more membranes interrupting the duodenal lumen. The classic double-bubble appearance is almost invariably associated with polyhydramnios, makes the ultrasonographic diagnosis relatively straightforward. It is extremely important, however, to attempt to demonstrate the communication between the stomach and the first part of the duodenum. Associated anomalies are the rule rather than the exception with this disorder, occurring in more than half of cases. In particular, 30% of fetuses with duodenal atresia have Down syndrome; hence, prenatal diagnosis should be offered. By way of contrast, however, only 10% of Down syndrome fetuses have duodenal atresia. Other anomalies commonly associated with Down syndrome include skeletal, cardiac, and other gastrointestinal malformations. Renal anomalies are seen in about 8% of cases, and growth restriction is common. SMALL BOWEL OBSTRUCTION The incidence of small bowel obstruction is about 1 in 5000 births, but the prevalence of in utero or ultrasonographic detection may be somewhat higher. It is often difficult, if not impossible, to differentiate jejunal from ileal atresia, although the extent of bowel dilation is often a clue (more loops are present with ileal abnormalities. Polyhydramnios is often the initial clue to a small bowel obstruction and is present in most cases. Unfortunately, as with duodenal atresia, jejunal and ileal obstructive problems are invariably diagnosed late in pregnancy, specifically in the third trimester. Unlike duodenal atresia, however, nongastrointestinal anomalies are rare in these cases. Other intestinal tract anomalies are common, with up to 45% exhibiting malrotations or enteric duplications, for example. Distal ileal obstructions appear to have the most favorable prognosis. Multiple dilated loops of small bowel (more than 7 mm in diameter) are the typical features in these cases, often with increased peristalsis. Differentiating small bowel from large bowel obstruction is usually possible by the location of the loops, the absence of haustra in small bowel, and the presence of polyhydramnios. Colonic obstructions, however, are uncommonly diagnosed in utero, and Hirschsprung's disease (congenital aganglionic megacolon) is likely to present with dilated small bowel and polyhydramnios, making it difficult to differentiate from a jejunoileal lesion. ANORECTAL ATRESIA The incidence of anorectal malformations is about 1 in 5000 live births. The prenatal diagnosis of imperforate anus and other anorectal anomalies has been reported about 15 times. Generally, the diagnosis has been as part of a syndrome of multiple anomalies (eg, caudal regression syndrome, VACTERL or VATER syndromes, McKusick-Kaufman syndrome). VACTERL syndrome may have a number of concurrent abnormalities, including vertebral abnormalities, anorectal atresia, cardiac anomalies, tracheoesophageal fistulas, esophageal atresia, renal anomalies, and limb abnormalities. MECONIUM ILEUS Meconium ileus results from a distal ileal obstruction with abnormally thick, viscous meconium. When this is present, the fetus is almost certain to have cystic fibrosis (CF), although only 10% to 15% of infants with CF have the condition. The typical appearance of dilated ileum, with a normal jejunum, collapsed colon, and polyhydramnios, may be indistinguishable from other small bowel obstructions. In some cases, however, the bowel presents as an echogenic mass. MECONIUM PERITONITIS Meconium peritonitis is a condition resulting from a small bowel perforation. The perforation generally leads to a chemical peritonitis, which results in intraabdominal calcifications that are the characteristic ultrasonographic feature in this condition. ABDOMINAL CYST: DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS When faced with the dilemma of an anechoic, presumably cystic mass in the fetal abdomen, a systematic approach is critical to making an appropriate diagnosis. Preliminary assessments to make include: Location and orientation of the mass Relation to other abdominal organs Size and shape of the lesion Fetal gender Wall and contents of the cyst In addition, the change in appearance over time may be extremely helpful in difficult cases. (Some of these cystic-appearing abnormalities are covered in the preceding sections on bowel obstruction or meconium pseudocyst.) Ovarian cyst is among the more common anechoic abdominal anomalies seen in a female fetus in the third trimester. They are usually, although not exclusively, located within the lower fetal abdomen. They may change in position in the abdomen or pelvis and may undergo torsion because they are often on a pedicle. It is thought that these cysts arise as a result of hormonal stimulation from the mother and placenta. Mesenteric or omental cysts are usually located in the mid-abdomen and are frequently mobile. Enteric duplication cysts are generally tubular in appearance, do not communicate with the bowel, and are more common in male fetuses. Sacrococcygeal teratomas are solid masses, but they may have cystic components. They originally arise from the deep pelvis coccyx and may have both intrapelvic and extrapelvic components. Ascites HEPATOSPLENOMEGALY Enlargement of the liver or spleen may occur secondary to an isolated finding such as a liver tumor (hemangioendothelioma) or systemic abnormalities such as fetal hydrops.