From PLI`s Course Handbook Managing Complex Litigation 2007

advertisement

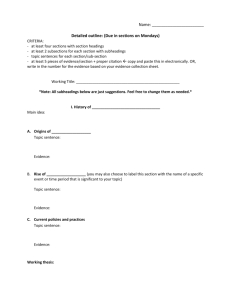

From PLI’s Course Handbook Managing Complex Litigation 2007: Legal Strategies and Best Practices in “HighStakes” Cases #12949 Get 40% off this title right now by clicking here. 4 E-MAIL AND DOCUMENT PRODUCTION IN NATIVE FORMAT J. Michael Rediker Haskell Slaughter Young & Rediker LLC 1 E-MAIL AND DOCUMENT PRODUCTION IN NATIVE FORMAT J. Michael Rediker Haskell Slaughter Young & Rediker LLC 2 E-mail and Document Production in “Native Format” Introduction: in early years of document production after electronic mail (“e-mail”) came into general business usage, retrieval and production of e-mail in any form was not nearly as convenient as it now can be, and e-mail was generally produced by litigants in the form of hard copy prints of “strings” of related e-mails, and any attachments to e-mails were also produced as hard copy print-outs. (For purposes of the following discussion, production in "TIFF" image format or PDF format is deemed equivalent to hard photocopy production, both in technical effect and in cost.) As software and techniques improved, and counsel also learned the meaning and significance of embedded data (“metadata”) in each piece of e-mail that you cannot “see” in a hard copy print-out, as well as the value of directly accessing e-mail attachments in their respective “native” software formats, such as an Excel spreadsheet (where you can see all the ranges, including hidden ranges, and the formulas), many counsel have sought production of email, with their attachments, in “native” format, just as they would be viewable on the originator’s own computer. Recognizing the major knowledge improvements gained by access to e-mails in native format, over what can be learned by viewing only hard copy print-outs of e-mails, many litigants have stoutly resisted production of e-mails in native format, raising a plethora of objections listed below. The law is still in a state of development for this area of document production. 1. Outline of Advantages of Native Format Production over Hard Copy (or TIFF Image) Production a. Ability to view embedded metadata, and the origination, author, tracking and authentication information that can be learned from metadata. b. Ability to view and analyze all attachments in their respective software formats; and to determine precisely which attachments belong to specific e-mails. c. of e-mails. Ability to determine the extent of, and see, the entirety of a string or chain d. Minimizes the opportunity for a producing party, whether inadvertently or otherwise, to separate pieces of e-mail chains or strings, or to separate the attachments from the transmitting e-mail, or to put the wrong attachment with an e-mail print-out, or to leave out part of a reply or chain of e-mail communications, or to omit an attachment. e. Great ease, facility and speed of word and phrase searching through a mass of e-mails produced in native format, using a variety of software and techniques, which simply cannot be done if the e-mails are only produced in hard copy form. f. Very large caches of e-mails can be conveniently stored and transported on a computer laptop in electronic, native format, then individual e-mails and/or their attachments can be printed out on an as-needed basis. 3 g. Counsel can “see” the e-mails in the chronological sequence in which the witness received them, and in any folders to which the witness may have assigned them after receipt. h. E-mails in native format can be rapidly retrieved and sorted by date, or sender, or recipient, for analytical purposes, electronically doing in seconds what could take hours or days to do by hand with hard copy print-outs. i. Cutting and pasting information into counsel’s outlines, or into briefs, from documents in native format, and attachments in native format, is greatly facilitated. j. Production in native format eliminates the need for expensive and bulky Optical Character Recognition (“OCR”) scans of hard copies, which producing parties have traditionally used. k. Production in native format results in an entirely accurate reproduction of a documents, e-mails, and any attachments (also in native format), which OCR scanning of hard copies cannot and does not guarantee. l. Access to e-mail caches in native format usually allows viewing and ascertainment of who received “BCC” or blind copies of e-mails. By contrast, the printing out of e-mails off an addressee’s (“To” or “CC”) computer (instead of the Author’s computer) does not show you “BCC” or blind copy recipients. 2. Traditional objections that have been made to Native Format Production; and some responses (leaving aside the impact of recent changes to the Federal Rules, see infra). a. It is claimed that it is more expensive. (Actually, if native format production is agreed to or ordered from the outset, before production commences, see, amended FRCP Rule 34(b)(iii), it is generally considerably less expensive to handle production in electronic form. The “key” is to broach and resolve the issue of native format production before the hard copy production commences.) b. Authenticity problems: e-mails or e-mail chains, or attachments, can be altered, thus posing problems of verification and checking before an e-mail is acceptable for use as an exhibit. (Of course, hard copies can be altered just as easily, if someone had a mind to do so. Producing parties usually create a “reference set” and any alterations of digital mail can be detected fairly easily from embedded metadata and/or simple side-byside comparison. Sometimes litigants store the e-mail caches with a third party service provider in a form or web site which prevents or detects alterations.) c. Hard copies can easily be bates numbered; native format e-mails, by their nature, are not bates numbered. (Counsel can agree, in native format production, to a variety of methods of identification, such as some form of electronic tagging or indexing, 4 or creating a single hard copy reference set which is bates numbered, or only printing out and bates numbering the e-mails from the cache that a party agrees by a date certain will be designated for possible use as exhibits, etc.). d. It is burdensome and onerous to review e-mails in native format for privileged communications, and especially to do so “on screen” as opposed to working with hard copy print-outs. (Actually, it is faster and usually more accurate and comprehensive, to review e-mails in native format for privileged communications, because - in addition to the ability to view them e-mail-by-e-mail on screen, or print them out and make such review - counsel and the client in advance of production can run electronic name searches and key word searches through the cache, to pick up potential privileged items.) e. Requested discovery of e-mail is often very comprehensive and intrusive, involving a large number of employee workstations and servers, and is disruptive to ordinary business operations. (But that is also true for e-mail production to be made in hard copy form.) f. Many companies do not have e-mail retention guidelines or controls, and key e-mails may have been automatically dropped, purged or archived and later discarded, from various workstations. (But that is also true for e-mail production to be made in hard copy form.) It is clear that under the December 1, 2006 amendments to the Federal Rules, summarized in the following section, many, if not most, of the above objections go away insofar as being excuses to avoid native format production. For example, Rule 34 now clearly permits a requesting party to specify production of e-mails and other electronically stored data in their native or original software formats. As a tradeoff, many of the traditional means of resisting native format production now will have to be couched in the form of objections under Rule 34 and requests for narrowing or limitation of discovery, and protective orders, or requests for cost-shifting, under revised Rule 26(b)(2). 3. December 2006 changes to Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, and Subsequent rule-making activity; rights to “native format” production recognized. Note: a full review of this complex subject would entail an entire separate panel session; therefore, only a summary will be furnished here. The new provisions relating to electronic discovery added to the Federal Rules do not resolve all the differences of opinion and approach, nor address each of the practical concerns mentioned in section 2 above, thus leaving room for negotiation, innovation and, in the absence of stipulation or agreement, court adjudication. Detailed information on rules changes and the summary of the Committee on Rules of Practice and Procedure of the Judicial Conference of the United States can be found at http://www.uscourts.gov/rules/congress0406.html. The following convenient summary is adapted in modified form from one provided by LexisNexis on an open web site 5 (https://www.lexisnexis.com/applieddiscovery/lawLibrary/courtRules.asp) which has relevant links to more detailed information available at www.uscourts.gov: Provisions in Federal Rules of Civil Procedure: Rule 16(b)(5)& (6): Pretrial Conferences, Scheduling Management. A scheduling order entered under this rule can include provisions for disclosure or discovery of electronically stored information and permit the parties to reach agreements for asserting claims of privilege or protection as trial-preparation material after production. The 2006 Advisory Committee Note points out, “[t]he amendment to Rule 16(b) is designed to alert the court to the possible need to address the handling of discovery of electronically stored information early in the litigation if such discovery is expected to occur.” Rule 26(a)(1)(B): General Provisions Governing Discovery; Duty of Disclosure; Required Disclosures; Methods to Discover Additional Matter. This rule requires that parties, without awaiting a discovery request, provide to other parties a copy of, or description by category and location of, electronically stored information. Rule 26(f)(3) & (4): General Provisions Governing Discovery; Duty of Disclosure; Conference of Parties; Planning for Discovery. This rule requires that parties, in their initial planning conference, discuss and develop a discovery plan addressing, among other things, issues relating to preserving discoverable information and any issues related to disclosure or discovery of electronically stored information. This includes the form or forms in which electronically stored information should be produced, and any issues relating to claims of privilege or protection as trial-preparation material. If the parties agree on a procedure to assert such claims after production, the parties should discuss whether to ask the court to include this agreement in an order. As with Rule 16(b), the 2006 Advisory Committee Note to Rule 26(f) emphasizes the need for electronic discovery issues to be addressed in detail and very early in the case, and speaks to the need for counsel to become familiar with their client’s information systems before such conference. Form 35: Report Parties Planning Meeting. The form adds a brief description of the parties' proposals for handling the disclosure or discovery of electronically stored information. Rule 26(b)(2)(B): General Provisions Governing Discovery; Duty of Disclosure; Discovery Scope and Limits; Limitations. 6 The rule provides that a party need not provide discovery of electronically stored information from sources that the party identifies as not reasonably accessible because of undue burden or cost. On both a motion to compel discovery or for a protective order, the burden is on the responding party to show that the information is not reasonably accessible because of undue burden or cost. Even if that showing is made, the court may nonetheless order discovery from that party if the requesting party shows good cause, considering the limitations that are set forth in Rule 26(b)(2)(C) (i.e. whether the discovery sought is cumulative, burden of expense outweighs the benefit, etc.). The court may also specify conditions for the discovery. The 2006 Advisory Committee Note to this amended provision states, “[u]nder this rule, a responding party should produce electronically stored information that is relevant, not privileged, and reasonably accessible, subject to the (b)(2)(C) limitations that apply to all discovery. The responding party must also identify, by category or type, the sources containing potentially responsive information that it is neither searching nor producing. The identification should, to the extent possible, provide enough detail to enable the requesting party to evaluate the burdens and costs of providing the discovery and the likelihood of finding responsive information on the identified sources.” Rule 26(b)(5)(B): General Provisions Governing Discovery; Duty of Disclosure; Discovery Scope and Limits; Claims of Privilege or Protection of Trial Preparation Materials; Information Produced. This rule provides that if information is produced in discovery that is subject to a claim of privilege or protection as trial-preparation material, the party making the claim may notify any party that received the information of the claim and the basis for it. After being notified, a party is required to promptly return, sequester, or destroy the specified information and any copies it has and may not use or disclose the information until the claim is resolved. A receiving party may promptly present the information to the court under seal for a determination of the claim. If the receiving party disclosed the information before being notified, it must take reasonable steps to retrieve it. The producing party is required to preserve the information until the claim is resolved. Rule 33(d): Interrogatories to Parties; Option to Produce Business Records. This rule provides that where the answer to an interrogatory may be derived from electronically stored information, and the burden of deriving the answer is substantially the same for the responding party and the requesting party, it is a sufficient answer to the interrogatory to specify the records from which the answer may be derived or ascertained. The responding party must allow the requesting party reasonable opportunity to examine, audit of inspect such records and make copies, compilations, abstracts or summaries. 7 The 2006 Advisory Committee Notes point out, among other things, that, “[d]epending on the circumstances, satisfying these provisions with regard to electronically stored information may require the responding party to provide some combination of technical support, information on application software, or other assistance. … A party that wishes to invoke Rule 33(d) by specifying electronically stored information may be required to provide direct access to its electronic information system, but only if that is necessary to afford the requesting party an adequate opportunity to derive or ascertain the answer to the interrogatory.” Rule 34(a) & (b): Production of Documents, Electronically Stored Information, and Things and Entry Upon Land for Inspection and other Purposes; Procedure. This rule provides that any party may serve on any other party a request to produce electronically stored information. The rule would also permit the party making the request to inspect, copy, test or sample electronically stored information stored in any medium from which information can be obtained translated if necessary by the responding party into a reasonably usable form. The rule provides that the request may specify the form or forms in which electronically stored information is to be produced. The producing party may object to the requested form or forms for producing electronically stored information stating the reason for the objection. If an objection is made to the form or forms for producing electronically stored information - or no form was made in the request - the responding party would be required to state the form or forms it intends to use. If a request does not specify the form or forms for producing electronically stored information, a responding party must produce the information in a form or forms in which it is ordinarily maintained or in a form or forms that are reasonably usable. A party need not produce the same electronically stored information in more than one form. As the 2006 Advisory Committee Note to Rule 34(b) now recognizes, “native format” production may be specified by a requesting party for electronically stored information, especially so as to permit the requesting party to take advantage of computer search features of electronic data: “[t]he amendment to Rule 34(b) permits the requesting party to designate the form or forms in which it wants electronically stored information produced. The form of production is more important to the exchange of electronically-stored information than of hard-copy materials … The rule recognizes that different forms of production may be appropriate for different types of electronically stored information. Using current technology, for example, a party might be called upon to produce word processing documents, e-mail messages, electronic spreadsheets, different image or sound files, and material from databases. … The rule therefore provides that the requesting party may ask for different forms of production for different types of electronically stored information. … Stating the intended form before the production occurs may permit the 8 parties to identify and seek to resolve disputes before the expense and work of production occurs. … If the form of production is not specified by party agreement or court order, the responding party must produce electronically stored information either in a form or forms in which it is ordinarily maintained or in a form or forms that are reasonably usable. … If the responding party ordinarily maintains the information it is producing in a way that makes it searchable by electronic means, the information should not be produced in a form that removes or significantly degrades this feature.” Rule 37(f): Failure to Make Disclosures of Cooperate in Discovery Sanctions; Electronically Stored Information. This section of Rule 37 provides that absent exceptional circumstances, a court may not impose sanctions under the rules on a party for failing to provide electronically stored information lost as a result of the routine, good faith operation of an electronic information system. The “good faith” requirement of this provision should be construed to require imposition of a “litigation hold” on electronically stored information which, but for such litigation hold, would otherwise be purged or discarded. The 2006 Advisory Committee Notes state, in relevant part, “[g]ood faith in the routine operation of an information system may involve a party’s intervention to modify or suspend certain features of that routine operation to prevent the loss of information, if that information is subject to a preservation obligation. A preservation obligation may arise from many sources, including common law, statutes, regulations, or a court order in the case. The good faith requirement of Rule 37(f) means that a party is not permitted to exploit the routine operation of an information system to thwart discovery obligations by allowing that operation to continue in order to destroy specific stored information that it is required to preserve. When a party is under a duty to preserve information because of pending or reasonably anticipated litigation, intervention in the routine operation of an information system is one aspect of what is often called a ‘litigation hold.’” Rule 45 Subpoena; Form; Issuance. This rule adds that a subpoena shall command each person to whom it is directed to attend and give testimony or to produce and permit inspection, copying, testing, or sampling of among other things, electronically stored information. In addition, a subpoena may specify the form or forms in which electronically stored information is to be produced. Subpoenas may be served to not only inspect materials but to copy, test or sample those materials. Similarly to Rule 34, if a subpoena did not specify the form or forms for producing electronically stored information, a responding party is required to produce the information in a form or forms in which it is ordinarily maintained or in a form or forms that are reasonably usable; and a party need not produce the same electronically stored 9 information in more than one form. As in Rule 26(b)(2)(B), a party need not provide discovery of electronically stored information from sources that the party identifies as not reasonably accessible because of undue burden or cost. On both a motion to compel discovery or for a protective order, the burden is on the responding party to show that the information is not reasonably accessible because of undue burden or cost. Even if that showing is made, the court may nonetheless order discovery from that party if the requesting party shows good cause, considering the limitations that are set forth in Rule 26(b)(2)(C) (i.e. whether the discovery sought is cumulative, burden of expense outweighs the benefit, etc.). The court may also specify conditions for the discovery. Similarly to Rule 26(b)(5)(B), if information is produced in response to a subpoena that is subject to a claim of privilege or protection as trial-preparation material, the party making the claim may notify any party that received the information of the claim and the basis for it. After being notified a party would be required to promptly return, sequester, or destroy the specified information and any copies it has and may not use or disclose this information until the claim is resolved. Proposed Rule of Evidence 502 In April 2007, the Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules approved Rule 502, a proposed amendment to the Federal Rules of Evidence. The amendment was proposed to address some of the issues raised by the effect of disclosure of attorney client and work product materials, in light of the costs of reviewing the volume of electronic information now being produced in litigation. The purpose of the rule is also to resolve the concern that any disclosure of protected information will operate as a subject matter waiver. See Hopson v. Mayor, 2005 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 29882 (D. Md. 2005), cited again below. The Rule is discussed in detail as an “action item” in the May 15, 2007 Report of the Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules. See http://www.uscourts.gov/rules/Reports/EV05-2007.pdf The Advisory Committee states that it will transmit Rule 502 to the Committee on Rules of Practice and Procedure with its recommendation that the proposed rule be approved and transmitted to the Judicial Conference for its consideration. Under the proposed rule, the disclosure of the attorney client or work product protected material does not operate as a waiver in a state or federal proceeding if the disclosure was inadvertent and made in connection with federal litigation or administrative proceedings and if the holder of the privilege took reasonable precautions to prevent disclosure and took reasonably prompt measures once the holder knew or should have known of the disclosure, to rectify the error, following the procedures in FRCP 26(b)(5)(B). In addition, in a federal or state proceeding, a disclosure of attorney client or work product privileged material when made to a federal public office or agency in the exercise of its regulatory authority does not operate as a waiver of the privilege in favor of nongovernmental persons or entities. The effect of disclosure to a state or local government agencies, however, is governed by applicable state law. The rule does not limit or expand the authority of a government agency to disclose communications or information to other governmental agencies. A federal court order concerning preservation or waiver of 10 privilege (in, for example, such agreements as "claw-back" or "quick peek" agreements) governs in federal or state proceedings-- even as to third parties. Agreements between the parties but not subject to a court order govern the parties to the agreement, but not third parties. 4. Suggestions for Making a Native Format Production Request for Electronically Stored Information a. Definitions. Definitions of sufficient breadth to accomplish your client’s discovery needs and goals should be incorporated into the discovery request, including definitions for “electronically stored information” and “information systems” and “native format” (or such alternative equivalent phrase as counsel may choose). At a minimum, “electronically stored information” should include: word processing documents; other documents; e-mail messages and any attachments to such messages; electronic spreadsheets; image files; video files; audio or sound files; presentations (e.g., Microsoft Powerpoint files); and databases. “Native format” generally means and refers to the original format of a type of electronically stored information in which such information was embodied at the time it was created by the software application used to create it; however, if you intend to specify a particular data format other than the original format used by the software application that created it, the definition of “native format” should be modified accordingly; see “b” below. You may wish to create definitions for “hard copy” format and “image” format. b. Specify the Format. It is critical under the amended Rules for the requesting party to include, from the first moment of making a discovery request, a specification of the computer file format of the data being requested. Examples of such specification might be: Microsoft Excel, for electronic spreadsheets; Microsoft Word or WordPerfect, for word processing files; Microsoft Outlook “pst” format for e-mail; Microsoft Office Access for databases; and so forth. With regard to e-mail, it is preferable to specify that “native format” be considered as a “pst” format file, if you plan to use Microsoft Outlook to review, search, sort or display such e-mail. If, for e-mail, you plan to use other forms of software than Microsoft Outlook, such as litigation support software, you may wish, instead, to specify that e-mail be output by the producing party in a different format than a “pst” file, using the format which is compatible with the data loading method called for by such litigation software. Note that Microsoft Outlook also has an “export” function allowing export to other formats such as comma separated values (useful for exporting databases of “contacts” information). If instead of “native” or computer file format, your need is for “hard copy” or “Tiff” image or “JPEG” image format, that, too, should be specified. Rule 34 only requires the responding party to produce in one format, so advance planning and specification of particular format on the front end is critical. c. Earliest possible specification. At the earliest stage of a case, before the opposing party has embarked upon expenditure of time and money, counsel should use the initial Conference under Rule 26, or informal discussion, to learn about the types of 11 information systems involved and the types and native formats of electronically stored information involved, and then frame the initial discovery requests so as to address such types of information systems and electronically stored information. The Rules allow the requesting party, in a way not previously afforded, the right to specify production formats, but if the requesting party does not do so promptly and in a timely manner, before discovery production work commences, that advantage under the amended Rules is lost. d. Avoid need for cost-shifting. Be careful what you ask for; it may wind up embroiling you in a lengthy fight and delay over cost-shifting and end up costing you a considerable amount of money. Using the Advisory Committee Notes’ seven guidelines to Rule 26(b)(2)(C), supra, and the Zubulake guidelines, supra, as planning tools, design a narrower, focused, supportable, case-specific, demonstrably relevant discovery request, than the very broad version you might otherwise have used in a case involving solely “hard copy” document production. Computer databases and computer backup files are often incredibly huge, and usually contain large masses of information not truly needed to prosecute or defend the litigation at hand. The goal, through discussion with the responding side, is to design a search and sorting process, which may even work in phases or stages, on a cost-effective basis, so as to target the portions of the backup files and databases or e-mail caches that more likely contain what you really need. 5. Costs attendant upon electronic discovery; other issues. a. The party of whom electronic discovery is requested often seeks cost-shifting to the requesting party. Courts have in recent years been developing guidelines for defining when some cost-shifting should occur, and to what extent. It is generally preferable to resolve such matters by negotiation and stipulation; such a resolution becomes easier when the obligation to produce in native electronic format is reciprocal, and the scope of the requests for data is pared to achievable, reasonable parameters, often by means of using an agreed set of “search terms” for electronic search and screening. (i) The normal principle is that each party bears its own costs of responding to discovery. Cf., Oppenheimer Fund, Inc. v. Sanders, 437 U.S. 340, 358 (1978) (“Under those [discovery] rules, the presumption is that the responding party must bear the expense of complying with discovery requests, but he may invoke the district court's discretion under Rule 26(c) to grant orders protecting him from ‘undue burden or expense’ in doing so, including orders conditioning discovery on the requesting party's payment of the costs of discovery.”); Rowe Entertainment, Inc. v. The William Morris Agency, Inc., 205 F.R.D. 421, 428-29 (S.D.N.Y. 2002) (holding, among other things, that plaintiffs would be required to bear the costs of producing e-mails from back-up tapes and hard drives; but if any defendant elected to conduct a full privilege review of its e-mails prior to production, that defendant would conduct such review at its own expense). (ii) Since “undue burden” under Rule 26(c) is determined on a case-by-case basis, Medtronic Sofamor Danek, Inc. v. Michelson, 229 F.R.D. 550, 553 12 (W.D.Tenn. 2003), citing, Bills v. Kennecott Corp., 108 F.R.D. 459, 463 (D.Utah 1985), courts have generally considered a number of factors in weighing whether to shift some part of or all of the discovery (in this case, electronic discovery) from the responding party to the requesting party. The newly-amended Rule 26(b)(2)(C) requires, in its text, a weighing of factors such as “the needs of the case, the amount in controversy, the parties’ resources, the importance of the issues at stake in the litigation, and the importance of the proposed discovery in resolving the issues.” As shown further below, the 2006 Advisory Committee Notes to Rule 26(b)(2)(C) provide more detailed factors as guides. In one of the earlier efforts at defining relevant factors for cost-shifting determinations in electronic discovery, Medtronic, supra, suggested the following factors, citing Rowe Entertainment, supra: (1) the specificity of the discovery requests; (2) the likelihood of discovering critical information; (3) the availability of such information from other sources; (4) the purposes for which the responding party maintains the requested data; (5) the relative benefit to the parties of obtaining the information; (6) the total cost associated with the production; (7) the relative ability of each party to control costs and its incentive to do so; and (8) the resources available to each party. In Medtronic, for example, after analyzing all eight factors, the decision found that some cost-shifting was warranted, and that defendant should bear part of the expense of electronic discovery, where the defendant sought 996 network backup tapes from plaintiff containing not only email but also 300 gigabytes of other electronic data not in a backed-up format. The Southern District of New York in a subsequent electronic discovery decision, Zubulake v. UBS Warburg LLC, 217 F.R.D. 309, 316-317 (S.D.N.Y. 2003) (often known as “Zubulake I”), found that the Rowe analysis omitted certain relevant factors and suggested a modified 7-factor set of guidelines for evaluating whether cost-shifting should occur in electronic “native format” discovery, and stated that such factors should not be weighted equally. The Zubulake factors were: 1. The extent to which the request is specifically tailored to discover relevant information; 2. The availability of such information from other sources; 3. The total cost of production, compared to the amount in controversy; 4. The total cost of production, compared to the resources available to each party; 5. The relative ability of each party to control costs and its incentive to do so; 6. The importance of the issues at stake in the litigation; and 7. The relative benefits to the parties of obtaining the information. Other courts have generally found Zubulake to be persuasive in this regard, in native format electronic discovery cases, see, e.g., Hagemeyer North America, Inc. v. Gateway Data Sciences Corp., 222 F.R.D. 594 (E.D.Wis. 2004); 13 OpenTV v. Liberate Technologies, 219 F.R.D. 474 (N.D.Cal. 2003); Wiginton v. CB Richard Ellis, Inc., 229 F.R.D. 568 (N.D. Ill. 2004) (adding to the Zubulake factors another which “considers the importance of the requested discovery in resolving the issues of the litigation”); Quinby v. WestLB AG, 2005 WL 3453908 (S.D.N.Y. Sep. 5, 2006); In re Veeco Instruments, Inc. Securities Litigation, 2007 WL 983987 (S.D.N.Y. Apr. 2, 2007) (describing Zubulake as “set[ting] forth a widely followed standard for determining when cost shifting is appropriate” in electronic discovery); W.E. Aubuchon Co. v. Benefirst, LLC, 2007 WL 1765610 (D.Mass. Feb. 6, 2007) (finding that the 2006 amendments to FRCP Rule 26 “to a large degree adopt Judge Scheindlin’s seven-step analysis” in Zubulake); Semsroth v. City of Wichita, 239 F.R.D. 630 (D.Kan. Nov. 15, 2006) (noting that “[t]he similarity between these [Rule 26(b)(2)] considerations and the factors in Zubulake I is readily apparent.”). The 2006 Advisory Committee Notes to revised Rule 26(b)(2)(C) now identify the following “appropriate considerations” that may be weighed in a costshifting analysis: (1) the specificity of the discovery request; (2) the quantity of information available from other and more easily accessed sources; (3) the failure to produce relevant information that seems likely to have existed but is no longer available on more easily accessed sources; (4) the likelihood of finding relevant, responsive information that cannot be obtained from other, more easily accessed sources; (5) predictions as to the importance and usefulness of the further information; (6) the importance of the issues at stake in the litigation; and (7) the parties' resources. It is reasonable to conclude that the current state of the law is that cost-shifting, with respect to electronic discovery, is not required or even the norm, but that this matter requires a case-by-case, fact-specific determination and, in the absence of agreement of the parties, the courts may upon motion consider an order to shift some of the costs, under amended Rule 26(b)(2), and in that event at least seven suggested factors should be considered. b. Mutually agreed protocols for native format production, including cost-bearing, are essential, and should be negotiated at the earliest stage of discovery planning and scheduling order drafting. c. Again, agreement is most easily reached on native format production issues when obligations, conditions and terms are reciprocal, applicable to all parties, and when the parties make sincere, creative efforts to understand the information systems involved, narrow the scope of requests, and ease the work and cost of searching large databases and 14 electronically stored caches of information through reasonable, agreed search terms and parameters. 6. Selected case law references of interest (note: many cases that are retrievable on the subject predate the December 2006 rules changes, supra). Zubulake v. UBS Warburg LLC, 217 F.R.D. 309, 316-317 (S.D.N.Y. 2003) (“Zubulake I”); and id, 216 F.R.D. 280 (S.D.N.Y. 2003) (“Zubulake III”); and id., 220 F.R.D. 212 (S.D.N.Y. 2003) (“Zubulake IV”) Lorraine v. Markel American Ins. Co., 241 F.R.D. 534 (D.Md. May 4, 2007) O’Bar v. Lowe’s Home Centers, Inc., 2007 WL 1299180 (W.D.N.C. May 2, 2007) Nova Measuring Instruments Ltd. v. Nanometrics, Inc., 417 F.Supp.2d 1121 (N.D.Cal. March 6, 2006) Klein-Becker USA, LLC v. Englert, 2007 WL 1795762 (D.Utah June 20, 2007) In re Verisign, 2004 WL 2445243 (N.D. Cal. March 10, 2004) Scotts Co. LLC v. Liberty Mut. Ins. Co., 2007 WL 1723509 (S.D. Ohio June 12, 2007) Quinby v. WestLB AG, 2005 WL 3453908 (S.D.N.Y. Sep. 5, 2006) In re Veeco Instruments, Inc. Securities Litigation, 2007 WL 983987 (S.D.N.Y. Apr. 2, 2007) W.E. Aubuchon Co. v. Benefirst, LLC, 2007 WL 1765610 (D.Mass. Feb. 6, 2007) Hagemeyer North America, Inc. v. Gateway Data Sciences Corp., 222 F.R.D. 594 (E.D.Wis. 2004) OpenTV v. Liberate Technologies, 219 F.R.D. 474 (N.D.Cal. 2003) Wiginton v. CB Richard Ellis, Inc., 229 F.R.D. 568 (N.D. Ill. 2004) Cornell Research Foundation, Inc. v. Hewlett Packard Co., 223 F.R.D. 55 (N.D.N.Y. 2003) Williams v. Massachusetts Mut. Life Ins. Co., 226 F.R.D. 144, 145-146 (D. Mass. 2005). Hopson v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, 232 F.R.D. 228 (D.Md. 2005) Order requiring preservation of computer-stored electronic mail, in Richardson v. TVIA, Inc., 2007 WL 1129344 (N.D. Cal. April 16, 2007) Spoliation of electronic mail, sanctions, in In re Krause, 2007 WL 1597937 (Bkrptcy D.Kan. June 4, 2007) Williams v. Spring/United Management Co., 2006 WL 3691604 (D.Kan. Dec. 12, 2006). Semsroth v. City of Wichita, 239 F.R.D. 630 (D.Kan. Nov. 15, 2006) In re Honeywell Intern. Inc. Securities Litigation, 230 F.R.D. 293 (S.D.N.Y. 2003) (electronic version of accountants’ workpapers) U.S. v. Sattar, 2003 WL 22510435 (S.D.N.Y. Nov. 5, 2003) (issue of production of electronically intercepted files in format other than their original electronic format) 15

![[Insert company logo] Attorney Work Product Privileged and](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006611124_1-6f0e88671e9874b3d173badc2d939d92-300x300.png)