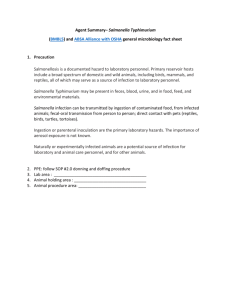

Animal Worker Questionnaire

advertisement

Form W: Animal Worker Questionnaire This form is a required attachment to all new protocols for all personnel to be involved in the project. An updated form must also be submitted any time an individual’s health status changes. Name: Date: Job Title: Department: Work Telephone #: Principal Investigator: Animal Worker Signature Date Principal Investigator Signature Date 1. With which specific animal species will you be working? 2. Please describe, in your own words, the type and extent of animal contact that you will have: 3. Have you had a tetanus shot? 4. Do you have any allergies? No No Yes – please provide date Yes – please specify below. 5. Have you had, or do you currently have, any problems working around animals? dates and the type of problems. No Yes - please list 6. List agents to be used in the proposed animal work: Chemical (includes anesthetics): Biological: Radioactive/Radiation: 7. Which of sections of the Diseases of Concern to Laboratory and Field Workers Exposed to Animals information on the following pages have you read? General Information [Required for all species] Rodents and Rabbits Birds Cattle, Sheep and Goats [should be read if working or conducting research on EKU farms] Pigs [should be read if working or conducting research on EKU farms] Fish, Amphibians and Reptiles 8. Other comments: 9. Are you under a physician’s care for any medical condition? No Yes – please have your physician evaluate/assess any risk to you as a consequence of your participation in this activity and complete the following evaluation section. Evaluation of patient by physician: Based on the description of the activity involving animals, which is being provided by my patient, ________________________________(patient’s name), and taking into account his/her physical and 1 psychological health status, I, _______________________________ (physician’s name), as his/her health care provider, certify him/her capable of safely engaging in the proposed activity, a) with no precautions/ accommodations necessary OR b) with the following precautions/ accommodations: Physician’s Signature Date 2 Diseases of Concern to Laboratory and Field Workers Exposed to Animals GENERAL INFORMATION: TO BE READ BY ALL PERSONNEL Tetanus: tetanus can be contacted via any animal bite or puncture wound of any type. Tetanus (lockjaw) is an acute, often fatal disease caused by the toxin of the tetanus bacillus. The bacterium usually enters the body in spore form, often through a puncture wound contaminated with soil, street dust, or animal feces, or through lacerations, burns, and trivial or unnoticed wounds. The Public Health Service Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends immunization against tetanus every 10 years. An immunization is also recommended if a particularly tetanus-prone injury occurs in an employee where more than five years has elapsed since the last immunization. Every lab and field worker exposed to animals is required to have up-to-date tetanus immunizations or formally signed waiver. If you need a tetanus immunization or have questions regarding this issue, please contact your primary care physician. Appropriate personal-hygiene practices (e.g., protective clothing, disposable gloves) should be employed to help prevent the contraction or spread of tetanus. Rabies: Rabies is included here because of the devastating nature of the disease and because EKU has a large population of researchers working in the field. (Refer also to the EKU Animal Bite SOP). Rabies is a devastating viral disease which results in severe neurological problems and death. Rabies virus infects all mammals, but the main reservoirs are wild and domestic canines, cats, skunks, raccoons, bats, and other biting animals, as well as groundhogs. The disease is virtually unheard of in commonly-used laboratory animals. However, the possibility of rabies transmission to dogs or cats with uncertain vaccination histories, and originating from an uncontrolled environment must be considered. Rabies virus is most commonly transmitted by the bite of a rabid animal, or by the introduction of virus-laden saliva into a fresh skin wound or an intact mucous membrane. Airborne transmission can occur in caves where bats roost. Personnel who handle tissue specimens or other materials potentially laden with rabies virus during necropsy or other procedures should be regarded as “at-risk” for infection. Rabies produces an almost invariably fatal encephalomyelitis. Patients experience a period of apprehension and develop headache, malaise, fever, and sensory changes at the site of any a priori animal-bite wound. The disease progresses to paresis or paralysis, inability to swallow and the related hydrophobia, delirium, convulsions, and coma. Death is often due to respiratory paralysis. Rabies is an endemic disease in Kentucky, especially in skunks and bats. Sporadic cases have been well-documented in other species of wildlife, as well as domestic animals. Animals and animal tissues fieldcollected in Kentucky for research or teaching should be handled with care. Precautions should take into account the facts that infected animals may shed the virus in the saliva before visible signs of illness appear, and that rabies virus can remain viable in frozen tissues for an extended period. Pre-exposure vaccine (human diploid cell vaccine) is available for those people at high risk of exposure. Researchers should consult the current Centers for Disease Control guidelines for the prevention of rabies infection. Personnel should rely on the use of protective clothing (especially the wearing of gloves when handling live or dead mammals), personal hygiene, and sanitation measures to prevent transmission of the disease. Aspergillosis Aspergillus is a common fungus that can be found in indoor and outdoor environments. Most people breathe in Aspergillus spores every day without being affected. Aspergillosis is a disease caused by this fungus and usually occurs in people with lung diseases or weakened immune systems. The spectrum of illness includes allergic reactions, lung infections, and infections in other organs. Aspergilla organisms can be found in any field or farm setting where large amounts of dust are raised by movement of birds, animals or people . Researchers should consult the current Centers for Disease Control guidelines for the prevention of aspergillosis infection. Appropriate personal-hygiene practices (e.g., protective clothing, filter masks, disposable gloves) should be employed to help prevent the contraction of aspergillosis. Lyme Disease Lyme disease is caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi and is transmitted to humans through the bite of infected ticks. Typical symptoms include fever, headache, fatigue, and a characteristic skin rash 3 called erythema migrans. If left untreated, infection can spread to joints, the heart, and the nervous system. Lyme disease is diagnosed based on symptoms, physical findings (e.g., rash), and the possibility of exposure to infected ticks; laboratory testing is helpful if used correctly and performed with validated methods. Most cases of Lyme disease can be treated successfully with a few weeks of antibiotics. Field researchers should consult the current Centers for Disease Control guidelines for the prevention of lyme disease infection. Steps to prevent Lyme disease include using insect repellent (see CDC recommendations for appropriate repellents) and removing ticks promptly. The ticks that transmit Lyme disease can occasionally transmit other tickborne diseases as well. Potential Risks for Women Who are Pregnant or May Become Pregnant: Women of child-bearing age should be aware of the potential risks to themselves and their unborn fetus that may be present working in the laboratory or farm environment. Zoonotic diseases associated with laboratory animals such as “Q” fever, Toxoplasmosis, and/or Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) are a concern as are some hazardous chemicals and compounds. Should you be pregnant or plan to become pregnant, it is strongly advised that you inform your supervisor and seek advice from your obstetrician or physician. This should be done as soon as you become aware of the change in your status. Toxoplasmosis: Toxoplasmosis is a disease caused by an organism called Toxoplasma gondii. Wild and domestic cats are the only definitive hosts of this organism. Usually this disease is quite mild and may be mistaken for a simple cold or viral infection. Swollen lymph nodes are common. In addition, it is common to have a mild fever, general washed-out feeling, and mild headaches. Rarely, more serious illness can occur, with involvement of the lungs, heart, brain or liver. Toxoplasmosis can have severe consequences in pregnant women and immunologically impaired people. Pregnant women should avoid contact with cat feces, soil, or uncooked meat. Cat litter and cat feces should be disposed of promptly before sporocysts become infectious, and gloves should be worn in the handling of potentially infective material. Researchers should consult the current Centers for Disease Control guidelines for the prevention of toxoplasmosis infection. Appropriate personalhygiene practices (e.g., protective clothing, disposable gloves) should be employed to help prevent the contraction or spread of infection. 4 Diseases carried by Rodents and Rabbits: The vast majority of mice, rats and rabbits used in research are bred in controlled environments under exacting microbiologic controls with frequent monitoring. These animals are generally free of any diseases transmissible to man. Wild caught rodents and rodents from facilities lacking standard practices may present a wide variety of zoonotic diseases including: VIRAL DISEASES Hantavirus Infection (Hemorrhagic Fever with Renal Syndrome; Nephropathia endemica) The Hantaviruses, which can cause severe hemorrhagic disease, are widely distributed in nature among rodent reservoirs. Rodents in several genera have been implicated in outbreaks of Hantavirus in the U.S. The transmission of Hantavirus infection is through the inhalation of infectious aerosols. Extremely brief exposure times (five minutes) have resulted in human infection. Rodents develop persistent, asymptomatic infections, and shed the virus in their respiratory secretions, saliva, urine, and feces for many months. Transmission of the infection can also occur by animal bite, or when dried materials contaminated with rodent excreta are disturbed, allowing wound contamination, conjunctiva exposure or ingestion to occur. Cases that have occurred in the laboratory animal environment have involved infected laboratory rats. Person-to-person transmission apparently is not a feature of Hantavirus infection. The form of the disease known as Nephropathia endemica is characterized by fever, back pain, and nephritis that cause only moderate renal dysfunction. The infection is usually self-limiting with proper treatment. The form of the disease that has been noted after laboratory animal exposure fits the classical pattern of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome. The infection is characterized by fever, headache, myalgia, gastrointestinal bleeding, bloody urine, severe electrolyte abnormalities, and shock. Human Hantavirus infections associated with the care and use of laboratory animals can be prevented through the isolation or elimination of infected rodents and rodent tissues before they can be introduced into the resident laboratory animal populations. Field researchers should consult the current Centers for Disease Control (CDC) guidelines for prevention hantavirus infection AND their professional literature for research guidelines related to hantavirus protection. Appropriate personalhygiene practices (e.g., protective clothing, disposable gloves) should be employed to help prevent the contraction or spread of infection. Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus Infection Human infection with Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis (LCM) associated with laboratory animal and/or pet contact has been recorded on several occasions. LCM is widely distributed among wild mice throughout most of the world, and presents a zoonotic hazard. Many laboratory animal species are infected naturally, including mice, hamsters, guinea pigs, nonhuman primates, swine and dogs. But the mouse has remained the primary concern in the consideration of this disease. Athymic, severe-combined-immunodeficiency (SCID), and other immunodeficient mice can pose a special risk by harboring silent, chronic infections, which present a hazard to personnel. The LCM virus produces a pantropic infection under some circumstances, and can be present in blood, cerebrospinal fluid, urine, nasopharyngeal secretions, feces, and tissues of infected natural hosts. Bedding material and other fomites contaminated by LCM-infected animals are potential sources of infection, as are infected ectoparasites. Lab workers can be infected by inhalation and contamination of mucous membranes or broken skin with infectious tissues or fluids from infected animals. Aerosol transmission is well documented. Humans develop an influenza-like illness characterized by fever, myalgia, headache, and malaise after an incubation period of 1-3 weeks. In severe cases of the disease, patients might develop meningoencephalitis. Central nervous system involvement has resulted in several deaths. Researchers should consult the current Centers for Disease Control (CDC) guidelines for the prevention of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection. Appropriate personal-hygiene practices (e.g., protective clothing, disposable gloves) should be employed to help prevent the contraction or spread of infection. BACTERIAL DISEASES Campylobacteriosis Organisms of the genus Campylobacter have been recognized as a leading cause of diarrhea in humans and animals. Numerous cases involving the zoonotic transmission of the organisms in pet and laboratory animals 5 have been documented. Results of prevalence studies on dogs, cats, nonhuman primates, and group-housed animals suggest that young animals readily acquire the infection and shed the organism. Campylobacter is transmitted by the fecal-oral route via contaminated food or water, or by direct contact with infected animals. Campylobacter spp. produces an acute gastrointestinal illness, which, in most cases, is brief and selflimiting. The clinical signs of Campylobacter enteritis include watery diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever, nausea, and vomiting. The infection generally resolves with specific antimicrobial therapy. Researchers should consult the current Centers for Disease Control (CDC) guidelines for the prevention of campylobacteriosis infection. Appropriate personal-hygiene practices (e.g., protective clothing, disposable gloves) should be employed to help prevent the contraction or spread of infection. Animal Biosafety Level 2 is recommended for activities using naturally or experimentally infected animals [Animal Biosafety Level 2 is assigned for animal work with those agents associated with human disease that pose moderate hazards to personnel and the environment]. Enteric Yersiniosis Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis are present in a wide variety of wild and domestic animals, which are considered the natural reservoirs for the organisms. The host species for Yersinia enterocolitica include rodents, rabbits, swine, sheep, cattle, horses, dogs, and cats. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis has a similar host spectrum and also includes various avian species. Human infections often have been associated with household pets, particularly sick puppies and kittens. Occasional reports of Yersinia infections in animals housed in the laboratory, such as guinea pigs, rabbits, and nonhuman primates, suggest that zoonotic Yersinia infection should not be overlooked in this environment. Yersinia spp. is transmitted by direct contact with infected animals through the fecal-oral route. Yersinia enterocolitica produces fever, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. In some cases, lesions may develop in the lower small intestine, resulting in a clinical presentation that mimics acute appendicitis. Researchers should consult the current Centers for Disease Control (CDC) guidelines for the prevention of enteric yersinia infection. Personnel should rely on the use of protective clothing, personal hygiene, and sanitation measures to prevent the transmission of the disease. Leptospirosis This is a contagious bacterial disease of animals and humans due to infection with Leptospira interrogans species. Rats, mice, field moles, hedgehogs, squirrels, gerbils, hamsters, rabbits, dogs, domestic livestock, other mammals, amphibians, and reptiles are among the animals that are considered reservoir hosts. Leptospires are shed in the urine of reservoir animals, which often remain asymptomatic and carry the organism in their renal tubules for years. The usual mode of transmission occurs through abraded skin or mucous membranes and is often related to direct contact with urine or tissues of infected animals. Inhalation of infectious droplet aerosols and ingestion of urine-contaminated food or water are also effective modes of transmissions. Clinical symptoms may be severe, mild or absent, and may cause a wide variety of symptoms including fever, myalgia, headache, chills, icterus and conjunctiva suffusion. The disease can usually be treated successfully with antibiotics. Researchers should consult the current Centers for Disease Control (CDC) guidelines for the prevention of leptospirosis infection. Personnel should rely on the use of protective clothing, personal hygiene, and sanitation measures to prevent transmission of the disease. Plague Plague, caused by Yersinia pestis, has not been identified as an important disease entity in the laboratory animal setting. However, focal outbreaks of this once devastating disease continue to be recognized worldwide, including the United States, where the disease exists in wild rodents in the western one-third of the country. In the United States, most human cases are related to wild rodents, but cats, dogs, coyotes, rabbits, and goats have also been associated with human infection. Most cases are the result of bites by infected fleas or contact with infected rodents. In human plague associated with nonrodent species, infection has resulted from bites or scratches, handling of infected animals (especially cats with pneumonic disease), ingestion of infected tissues, and contact with infected tissues. Nonrodent species can serve as transporters of fleas from infected rodents into the laboratory. Human plague has a localized (bubonic) form and a septicemic form. In bubonic plague, patients have fever and large, swollen, inflamed, and tender lymph nodes, which can suppurate. The bubonic form can progress 6 to septicemic plague, with spread of the organism to diverse parts of the body, including lungs and meninges. The development of secondary pneumonic plague is of special importance because aerosol droplets can serve as a source of primary pneumonic or pharyngeal plague, creating a potential for epidemic disease. Preventive measures in a laboratory animal facility should encompass the control of wild rodents and the quarantine, examination, and ectoparasite treatment of incoming animals with potential infection. Vaccines are available for personnel in high-risk categories, but confer only brief immunity. Animal Biosafety Level 2 practices, as well as containment equipment and facilities, are recommended for personnel working with naturally or experimentally infected animals. Researchers should consult the current Centers for Disease Control guidelines for the prevention of plague. Appropriate personal-hygiene practices (e.g., protective clothing, disposable gloves) should be employed to help prevent the contraction or spread of infection. Rat-Bite Fever Rat-bite fever is caused by either Streptobacillus moniliformis or Spirillum minor, two microorganisms that are present in the upper respiratory tracts and oral cavities of asymptomatic rodents, especially rats. These organisms are present worldwide in rodent populations, although efforts by commercial suppliers of laboratory rodents to eliminate Streptobacillus moniliformis from their rodent colonies now appear to have been largely successful. Most human cases result from a bite wound inoculated with nasopharyngeal secretions, but sporadic cases have occurred without a history of rat bite. Infection also has been transmitted via blood of an experimental animal. Persons working or living in rat infested areas have become infected even without direct contact with rats. In Streptobacillus moniliformis infections, patients develop chills, fever, malaise, headache, and muscle pain. A rash, most evident on the extremities, follows. Arthritis occurs in 50% of Streptobacillus moniliformis cases, but is considered rare in Spirillum minor infections. Complications of untreated cases of the disease include abscesses, endocarditis, pneumonia, and hepatitis. Researchers should consult the current Centers for Disease Control guidelines for the prevention of rat-bite fever. Proper animal handling techniques are critical to the prevention of rat-bite fever. Personnel should rely on the use of protective clothing, personal hygiene, and sanitation measures to prevent transmission of the disease. Salmonellosis Enteric infection with Salmonella spp. has a worldwide distribution among humans and animals. Despite the efforts to eliminate the organism in laboratory animal populations, carriers continue to occur, as a result of infection by contaminated food, or other environmental sources of contamination. These carriers represent a source of infection for other animals and for personnel who work with animals. Surveys in dogs and cats have indicated that the prevalence of salmonellosis infection remains approximately 10% among random-source animals. Salmonella spp. continue to be recorded frequently among recently imported nonhuman primates. Infection with Salmonella spp. is nearly ubiquitous among reptiles. Avian sources are often implicated in food borne cases of human Salmonellosis. Birds in a laboratory animal facility should be considered likely sources for zoonotic transmission. The organism is transmitted by the fecal-oral route, via food derived from infected animals, or from food contaminated during preparation, contaminated water, or direct contact with infected animals . Salmonella spp. infection produces an acute, febrile enterocolitis. Septicemia and focal infections occur as secondary complications. Focal infections can be localized in any tissue of the body, so the disease has diverse manifestations. Researchers should consult the current Centers for Disease Control guidelines for the prevention of salmonellosis. Personnel should rely on the use of protective clothing, personal hygiene, and sanitation measures to prevent the transmission of salmonellosis. Animal Biosafety Level 2 is recommended for activities using naturally or experimentally infected animals. FUNGAL DISEASES Dermatomycosis (Ringworm) Many species of animals are susceptible to fungi (dermatophyte) that cause the condition known as ringworm. Dogs, cats, and domestic livestock are the most commonly affected animals. The skin lesion usually spreads in a circular manner from the original point of infection, giving rise to the term “ringworm.” The complicating factor is that cats and rabbits may be asymptomatic carriers of the pathogens that can cause the condition in humans. Dermatophyte spores can become widely disseminated and persistent in the 7 environment, contaminating bedding, equipment, dust, surfaces, and air, resulting in the infection of personnel who have no direct animal contact. In humans, the disease usually consists of small, scaly, semi-bald, grayish skin patches with broken, lusterless hairs, with itching. Lesions often are on the hands, arms or other exposed areas, but invasive and systemic infections have been reported in immunocompromised people. Researchers should consult the current Centers for Disease Control guidelines for the prevention of ringworm infection. Appropriate personal-hygiene practices (e.g., protective clothing, disposable gloves) should be employed to help prevent the contraction or spread of infection. PROTOZOAN DISEASES Cryptosporidiosis Cryptosporidium spp. have a cosmopolitan distribution and have been found in many animal species, including mammals, birds, reptiles, and fishes. Among the laboratory animals, lambs, calves, pigs, rabbits, guinea pigs, mice, dogs, cats, and nonhuman primates can be infected with the organisms. Cryptosporidiosis is common in young animals, particularly ruminants and piglets. Cryptosporidiosis is transmitted by the fecal-oral route and can involve contaminated water, food, and possibly air. Many human cases involve human-to-human transmission or possibly the reactivation of subclinical infections. Several outbreaks of the disease have been associated with surface water contaminants. Zoonotic transmission of the disease to animal handlers has been recorded, including among handlers of infected infant nonhuman primates. Although cryptosporidiosis has become identified widely with immunosuppressed people, the ability of the organism to infect immunocompetent people also has been recognized. In humans, the disease is characterized by cramping, abdominal pain, profuse watery diarrhea, anorexia, weight loss, and malaise. Symptoms can wax and wane for up to 30 days, with eventual resolution. However, in immunocompromised persons, the disease can have a prolonged course that contributes to death. Researchers should consult the current Centers for Disease Control guidelines for the prevention of cryptosporidiosis infection. Appropriate personal-hygiene practices (e.g., protective clothing, disposable gloves) should be employed to help prevent the contraction or spread of infection. Giardiasis Many wild and laboratory animals serve as a reservoir for Giardia spp., although cysts from human sources are regarded as more infectious for humans than are those from animal sources. Dogs, cats, and nonhuman primates are most likely to be involved in zoonotic transmission. Drinking untreated water can be a source of Giardia spp. organisms. Giardiasis is transmitted by the fecal-oral route chiefly via cysts from an infected person or animal. The organism resides in the upper gastrointestinal tract where trophozoites feed and develop into infective cysts. Humans and animals have similar patterns of infection. Infection can be asymptomatic, but anorexia, nausea, abdominal cramps, bloating, and chronic, intermittent diarrhea are often seen. Researchers should consult the current Centers for Disease Control guidelines for the prevention of giardiasis infection. Appropriate personal-hygiene practices (e.g., protective clothing, disposable gloves) should be employed to help prevent the contraction or spread of infection. Additional sources to consult: www.cdc.gov Centers for Disease Control (CDC) website. National Institutes of Health (NIH). August 2002. Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. NIH, Office for Protection from Research Risks, Washington, DC. National Research Council (NRC, the “Guide”). 2011. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. NRC, Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, Commission on Life Sciences, National Academies Press, Washington, DC. National Research Council (NRC). 1997. Occupational Health and Safety in the Care and Use of Research Animals. NRC, Institute of Animal Laboratory Resources, Commission on Life Sciences, National Academies Press, Washington, DC. 8 Diseases carried by Cattle, Sheep and Goats Rabies Refer to page one of this document. Tuberculosis Tuberculosis of animals and humans is caused by acid-fast bacilli of the genus Mycobacterium. Cattle, birds, and humans serve as the main reservoirs for these mycobacteria . Many laboratory animal species, to include nonhuman primates, swine, sheep, goats, rabbits, cats, dogs, and ferrets, are susceptible to infection, and contribute to the spread of the disease. Animals confirmed positive will normally be euthanatized. Mycobacterium tuberculosis is transmitted via aerosols from infected animals or tissues. This mode of transmission also applies to most of the other mycobacterial species that might be encountered in laboratory animal contact. Humans can contract the disease in the laboratory through exposure of infectious aerosols generated by the handling of dirty bedding, the use of high-pressure water sanitizers, or the coughing of animals with respiratory involvement. The bacteria may also be shed in droppings, or from skin exudates resulting from infected, ruptured lymph nodes. The most common form of tuberculosis reflects the involvement of the pulmonary system and is characterized by soft coughing, which progresses to the coughing of blood or blood-stained sputum. Other forms of the disease can involve any tissue or organ system, due to the spread via the blood stream. General symptoms as the disease progresses include weight loss, fatigue, lassitude, fever, and chills. The diagnosis of tuberculosis in humans and animals relies primarily on the use of the intradermal tuberculin skin test. Researchers should consult the current Centers for Disease Control guidelines for the prevention of tuberculosis infection. Personnel should rely on the use of protective clothing (face shields or masks, goggles, and gloves), personal hygiene, and sanitation measures to prevent transmission of the disease. Brucellosis Brucellosis, also called Bang's disease, undulant fever, is a highly contagious zoonosis caused by ingestion of unpasteurized milk or undercooked meat from infected animals or close contact with their secretions. Brucella spp. organisms function as facultative intracellular parasites, causing chronic disease, which usually persists for life. Brucellosis has been recognized in animals, including humans, since the 20th century. The symptoms are like those associated with many other febrile diseases, but with emphasis on muscular pain and profuse sweating. The duration of the disease can vary from a few weeks to many months or even years. In the first stage of the disease, septicemia occurs and leads to the classic triad of undulant fevers, sweating (often with characteristic smell, likened to wet hay), and migratory arthralgia and myalgia (joint and muscle pain). Researchers should consult the current Centers for Disease Control guidelines for the prevention of brucellosis. Appropriate personal-hygiene practices (e.g., protective clothing, disposable gloves) should be employed to help prevent the contraction or spread of infection. Coxiella burnetti (Q Fever) Q fever is a worldwide disease with acute and chronic stages caused by the bacteria Coxiella burnetii. Cattle, sheep, and goats are the primary sources of infection. Organisms are excreted in milk, urine, and feces of infected animals. During birthing the organisms are shed in high numbers within the amniotic fluids and the placenta. The organism is extremely hardy and resistant to heat, drying, and many common disinfectants which enable the bacteria to survive for long periods in the environment. Infection of humans usually occurs by inhalation of these organisms from air that contains airborne barnyard dust contaminated by dried placental material, birth fluids, and excreta of infected animals. Other modes of transmission to humans, including tick bites, ingestion of unpasteurized milk or dairy products, and human to human transmission, are rare. Humans are often very susceptible to the disease, and very few organisms may be required to cause infection. Symptoms begin 2-3 weeks after infection. Symptoms include high fevers (104oF), headache, malaise, myalgia, abdominal and chest pain, chills and/or sweats, vomiting and/or diarrhea. Pregnant women who become infected may miscarry. This is a difficult disease to diagnose and treat. Researchers should consult the current Centers for Disease Control guidelines for the prevention of Q Fever. Personnel should rely on the use of protective clothing (face shields or masks, goggles, and gloves), personal hygiene, and sanitation measures to prevent transmission of the disease. Orf virus infection (Sore mouth) 9 “Sore mouth,” also known as “scabby mouth,” or contagious ecthyma, is a viral infection caused by a member of the poxvirus group and is an infection primarily of sheep and goats. Orf virus infection is found around the world. It is spread by fomites such as trucks, harnesses and buckets. Early in the infection sores appear as blisters and then become crusty scabs, typically found on the lips, muzzle, and in the mouth. Lesions eventually become ‘scabby’ and fall off. The scabs are loaded with virus which can last for long periods in the environment. A person who comes into contact with virus from an infected animal or equipment (such as a harness) can potentially get infected. People often develop sores on their hands. The sores may be painful and can last for 2 months. People do not infect other people. Sores usually heal without scarring. Researchers should consult the current Centers for Disease Control guidelines for the prevention of Orf virus infection. Appropriate personal-hygiene practices (e.g., protective clothing, disposable gloves) should be employed to help prevent the contraction or spread of infection. Leptospirosis Refer back to Rodents and Salmonellosis Refer back to Rodents and Campylobacteriosis Refer back to Rodents and Dermatomycosis (Ringworm) Refer back to Rodents and Rabbits section. Rabbits section. Rabbits section. Rabbits section. 10 Diseases carried by Pigs: Swine Influenza virus Swine influenza (swine flu) is a respiratory disease of pigs caused by type A influenza viruses that regularly cause outbreaks of influenza in pigs. Influenza viruses that commonly circulate in swine are called “swine influenza viruses” or “swine flu viruses.” Like human influenza viruses, there are different subtypes and strains of swine influenza viruses. The main swine influenza viruses circulating in U.S. pigs in recent years are: swine triple reassortant (tr) H1N1 influenza virus, trH3N2 virus and trH1N2 virus. Swine flu viruses do not normally infect humans. However, sporadic human infections with swine influenza viruses have occurred. When this happens, these viruses are called “variant viruses.” Common signs in sick pigs include fever, depression, coughing (barking), discharge from the nose or eyes, sneezing, breathing difficulties, eye redness or inflammation, and going off feed. Signs of swine flu in people are similar to a human flu virus infection and include fever, lethargy, lack of appetite and coughing. Researchers should consult the current Centers for Disease Control guidelines for the prevention of swine flu infection. Personnel should rely on the use of protective clothing (face shields or masks, goggles, and gloves), personal hygiene, and sanitation measures to prevent transmission of the disease. Streptococcus suis Streptococcus suis causes a host of problems in pigs: meningitis, arthritis, heart valve infections, polyserositis, pneumonia, vaginitis and abortions. The bacteria can reside in the tonsil and/or genital tract of pigs; 35 types of Streptococcus suis have been identified. The most common clinical signs are meningitis (nervous signs) and arthritis (joint swellings) in nursery pigs. Strep infections are a common problem in today's production units, even in some of the “high health” herds. Humans can be infected with S. suis when they handle infected pig carcasses or meat, especially with exposed cuts and abrasions on their hands. Human infection can be severe, with meningitis, septicaemia, endocarditis, and deafness as possible outcomes of infection. Researchers should consult the current Centers for Disease Control guidelines for the prevention of Streptococcus suis infection. Appropriate personal-hygiene practices (e.g., protective clothing, disposable gloves) should be employed to help prevent the contraction or spread of infection. Toxoplasma gondi (undercooked pork, very bad for fetus of pregnant woman) Toxoplasma gondi does not cause disease in swine. Humans will rarely be infected with T. gondi from exposure to pigs. Infection will primarily be from eating undercooked pork, or managing to get the organism from raw pork to one’s mouth. Pork should be cooked to 145oF and rested before carving. Humans infected with T. gondi may exhibit ‘flu like symptoms’. Human fetuses and humans with compromised immune systems are very susceptible to T. gondi infections. Appropriate personal-hygiene practices (e.g., protective clothing, disposable gloves) should be employed as safety precautions. Yersinia coli Refer back to Rodent and Rabbit section. Campylobacteriosis Refer back to Rodents and Rabbits section. Salmonellosis Refer back to Rodents and Rabbits section. 11 Diseases carried by Birds: Histoplasmosis Histoplasmosis is a disease caused by the fungus Histoplasma capsulatum. The fungus lives in the environment, usually in association with large amounts of bird or bat droppings. Lung infection can occur after a person inhales airborne, microscopic fungal spores from the environment; however, many people who inhale the spores do not get sick. The symptoms of histoplasmosis are similar to pneumonia, and the infection can sometimes become serious if it is not treated. People with a compromised immune system will likely have more severe or disseminated disease. Researchers should consult the current Centers for Disease Control guidelines for the prevention of histoplasmosis infection. Personnel should rely on the use of protective clothing (face shields or masks, goggles, and gloves), personal hygiene, and sanitation measures to prevent transmission of the disease. Cryptococcosus Cryptococcosis is an infection caused by fungi that belong to the genus Cryptococcus. Two species – Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii – cause nearly all cryptococcal infections in humans and animals. Although many people who develop cryptococcosis have weakened immune systems, some are previously healthy. Cryptococcus neoformans can be found in soil throughout the world. People at risk can become infected after inhaling microscopic, airborne fungal spores. Sometimes these spores cause symptoms of a lung infection, but other times there are no symptoms at all. In people with weakened immune systems, the fungus can spread to other parts of the body and cause serious disease. Researchers should consult the current Centers for Disease Control guidelines for the prevention of cryptococcosus infection. Personnel should rely on the use of protective clothing (face shields or masks, goggles, and gloves), personal hygiene, and sanitation measures to prevent transmission of the disease. Psittacosis Cause is Chlamydophila (or Chlamydia) psittaci, a gram-negative bacterium. In humans, infection is characterized by fever, chills, headache, muscle aches, and a dry cough. Pneumonia is often evident on chest x-ray. Endocarditis, hepatitis, and neurologic complications may occasionally occur. Severe pneumonia requiring intensive-care support may also occur. Fatal cases have been reported. Infection is acquired by inhaling dried secretions from infected birds. The incubation period is 5 to 19 days. Although all birds are susceptible, pet birds (parrots, parakeets, macaws, and cockatiels) and poultry (turkeys and ducks) are most frequently involved in transmission to humans. Personal protective equipment (PPE) should be used when handling birds or cleaning their cages. Psittacosis is a reportable condition in most states. Researchers should consult the current Centers for Disease Control guidelines for the prevention of psittacosis infection. Personnel should rely on the use of protective clothing (face shields or masks, goggles, and gloves), personal hygiene, and sanitation measures to prevent transmission of the disease. Salmonellosis Refer to Rodents and Rabbits section. E. coli enterocolitis Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacteria normally live in the intestines of people and animals. Most E. coli are harmless and actually are an important part of a healthy human intestinal tract. However, some E. coli are pathogenic, meaning they can cause illness; either diarrhea or illness outside of the intestinal tract (urinary tract infections, respiratory illness and pneumonia, and other illnesses). The types of E. coli that can cause diarrhea can be transmitted through contaminated water or food, or through contact with animals or persons. E. coli consists of a diverse group of bacteria. Pathogenic E. coli strains are categorized into pathotypes. Six pathotypes are associated with diarrhea and collectively are referred to as diarrheagenic E. coli. Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC)—STEC may also be referred to as Verocytotoxin-producing E. coli (VTEC) or enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC). This pathotype is the one most commonly heard about in the news in association with foodborne outbreaks. Researchers should consult the current Centers for Disease Control guidelines for the prevention of Escherichia coli infection. Personnel should rely on the use of protective clothing (face shields or masks, goggles, and gloves), personal hygiene, and sanitation measures to prevent transmission of the disease. Tuberculosis 12 Refer to Cattle, Sheep and Goats section. 13 Diseases carried by Fish, Amphibians and Reptiles (see also the following table entitled ‘Zoonoses of Fish, Amphibians and Reptiles’; www.apsu.edu/files/iacuc/Zoonoses-fish-reptiles-amphibians.pdf) Pentastomid Worms Pentastomid worms are found in many different species of turtles, lizards and snakes. The worms live in their lungs and nasal passages. Reptiles cough up the eggs and then swallow them, where they are passed out of the body in the stool. A reptile can spread millions of eggs around its enclosure this way. Transmission to humans typically occurs when animals or waste are handled and then the person touches his/her mouth or eyes. If eggs enter the human body, they hatch and become larvae. The larvae penetrate through human intestines and travel through the bloodstream, finding new homes in the liver, lungs or lymph nodes of their new host. The worms do not respond to medication and must be surgically removed. Appropriate personal-hygiene practices (e.g., protective clothing, disposable gloves, hand-washing) should be employed to help prevent contracting diseases or parasites associated with amphibians, fish and reptiles. Researchers should consult the current Centers for Disease Control guidelines for the prevention of the listed zoonoses associated with fish, amphibians and reptiles. 14 EKU IACUC Form W: Animal Worker Questionnaire, Page 2 16