Health and human services management or administration is

A Model to Determine the Skills Needed by Managers in Human Service

Organizations

Gregory A. Moore

Austin Peay State University

Health and Human Performance

P.O. Box 4445

Clarksville, TN 37044

Tel. 931-221-6341

Fax: 931-221-7040

E-mail: mooreg@apsu.edu

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study is to determine if the inherent nature of the human service organization reveals what special or additional skills a manager needs to manage these organizations. A definition for the human service organization is developed. This definition and characteristics of the human service organization form the basis of the model to derive the special attributes that relate to management skills. Four groups of managerial special skills are identified that compose those needed to address the key characteristics of the human service organization

Problem Statement

Do managers in the human service organization need special skills different from managers in other organizations? Is there something in the definition or characteristics of the human service organization (HSO) that would indicate there is a set of special skills needed to manage this specialized form of organization? Is there a universally recognized definition of the human service organization? What are the characteristics of the HSO? What do these characteristics tell us about the HSO and the way it should be managed?

However, do we have a useable definition of the human service organization? If not, how should the HSO be defined? If not, does it mean that the processes and skills needed by managers in human services organizations are not clear? Are they the same as any other manager for any other organization? Can they be determined?

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study is to determine if the inherent nature of the human service organization reveals what skills managers of these organizations need and how these skills may be different from what managers of typical business organizations need. If the definition and characteristics can be found, can a model indicate if those skills are needed?

1

Importance

Human services management or administration is sometimes taught as a subject with separate content within schools or departments of business or management. We also find health care or human services management taught as a branch or separate branches in a more clinical setting of another functionally related field or department like medicine, human development, health, or human performance. Public management at times becomes the designated alternative to the more commonly available business management department for those who want a career in health and human services administration. Would a model based on the inherent characteristics of health care and human services organizations bring us closer to understanding the skills, knowledge, and management processes needed to be prepared to manage the human service organization?

If the skills and training needed to manage health care organizations were more easily determined and universally accepted, students and teachers in the field could more easily decide what to learn or what to teach. Better information may help determine if we should separate human services management training from other management training. If there are no significant differences in the typical business organization and the human service organization, then can we collapse separate managerial departments from different fields into one organizational management discipline? If there are differences, we need to identify them, determine how significant they are, and determine systemically how they can be translated into useable information for making choices about teaching human services management.

Examining Existing Definitions and Characteristics of the HSO

A first step in approaching this question is to examine the definitions and characteristics of a human service organization described by others. Next we will determine whether the characteristics of these organizations are different from the typical business or non-human service organization. The following focuses on finding existing definitions of the human services organization, how others describe or characterize it and its system and on discovering comparisons of human service organizations to other organizations.

A review of books available as texts from several areas of health and human service field, including management, finance, economics, organizational behavior, human resources, and law, revealed few definitions of the health care or human services organization. Longest, Rakich, and

Darr (2004: 5) refer to the health care organization, stating, “HSOs are entities that provide the organizational structure within which the delivery of health service is made directly to consumers, whether the purpose of the services are preventive, acute, chronic, restorative, or palliative.” Gapenski (2005: 3) in categorizing types of industries in health services delivery states, “The health services industry consists of providers of health services such as medical practices, hospitals, clinics, nursing homes, and home health care agencies.” Gapenski (2005) then lists categories for other organizations in the system, such as health insurance, managed care, pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, medical equipment suppliers, and educational and research agencies. Cleverley and Cameron (2003) define the health service organization as the basic provider of health service, but add that it is also a business. Other books available as texts revealed few outright definitions, but scores of descriptions and characteristics of health care organizations and the health care system.

2

The HSO Environment

The broad view of the health care system in which the health services organization operates is described by Sultz and Young (2006: xiii), who suggest it includes “… thousands of independent medical practices and partnerships, managed care and provider organizations, public and nonprofit institutions such as hospitals, nursing homes and other specialized care facilities and major private corporations.” Goldsmith (2005: 17) summarizes the health care system as

“…expensive, complex, and quite fragmented…” and not “…simply a group of well defined and integrated components, all of which relate to a common goal.” Similarly Santerre and Neun

(2004) describe the health care system as complex in part due to constantly changing providers.

Gary Filerman argues in a Foreword for Fried, Fottler, and Johnson (2005) that health services administration is challenging due to the complexity of the health care organization and consequential as it directly affects the quality of life in communities. Goldsmith (2005: 17) says the system is characterized by “overlap, waste, and multiplicity of goals.” Kilpatrick and Johnson

(1999) describe the increasing competition and government control in health care. McConnell

(2003) says competition in health care is a way of life.

What Constitutes an HSO?

Many authors illustrate the breadth of the answer to this question by naming a wide range of participant organizations. Santerre and Neun (2004) offer a specific listing of participants, including hospitals, long term care facilities, private health insurance carriers, physician services, pharmaceuticals, physicians and dentists, nursing homes, mental retardation facilities, consumers, and government agencies. Wolper (2004) adds laboratories to the list. Goldsmith

(2005) includes a wide range of organizations including hospitals and the corner drugstore, but for his specific purposes in his text excludes herbalists and therapeutic masseurs, yet recognizes them as a part of the much larger system. Similarly, McConnell (2003) describes the modern health care setting as more than the hospital and private clinic, and includes long term care facilities, rehabilitation services, medical and dental services, freestanding surgical centers, home health agencies, laboratories, hospices, insurance companies, professional medical transportation companies, pharmacies, and pharmaceuticals. Organizations considered in the health care delivery system also include those involved in education, research, and foundation work, according to Shortell and Kaluzny (2000).

Addressing Basic Management Functions

While authors may differ over the number and types of management functions that must be addressed by any organization, several authors agree the health services organization like any other organization must address basic management functions, such as planning, organizing, and controlling (Goldsmith, 2005; Liebler & McConnell, 2004; Longest, Rakich, & Darr, 2004;

McConnell, 2003).

A Special Human Purpose and Demand for Quality

3

Like any other organization the health care services organization must meet people’s needs

(McConnell, 2003). However, McConnell (2003: 24) observes that while the health services organization has “a uniquely humane mission,” a simple comparison of health care with industry is insufficient to understand the real differences. He applies Likert’s “scale of organizations” to describe health care organizations in terms of the “job organization system” and the “cooperative motivation system” (McConnell, 2003: 25). Other authors describe the purpose of the health services organization as a participant in the continuum of human services from pre-birth to adulthood to long term care (Longest, Rakich, and Darr, 2004). Outcomes produced by the human service organization are more difficult to measure (Jacobs & Rapoport, 2002; Shortell &

Kaluzny, 2000). Yet a demand for greater efficiency and effectiveness faces the health services organization (Longest, et al., 2004). High quality is demanded from the human services organization (Jacobs & Rapoport, 2002; Longest, et al., 2004; McConnell, 2003; Shortell &

Kaluzny, 2000). Longest, et al. (2004) note that health services organizations have routinely faced high expectations by consumers and patients, clinicians, and those who pay for health care.

Continued high quality care will be demanded despite constant pressure to contain or reduce costs (McConnell, 2003).

Financial operations

Richard L. Clarke in a Foreword for a book authored by Nowicki (2004: ix) says, “Healthcare is unique in the way it is financed. It is characterized by a pluralistic system of public and private delivery of services that is unmatched in other industries.” Santerre and Neun (2004) chart a model of how the health care system is financed, using triangular charts involving sponsors, patients, third party insurers, and health care providers anchoring the flow of fees, services, payments as reimbursement, premiums, and insurance coverage. According to Cleverley and

Cameron (2003: 18), “One of the most important financial differences between health care firms and other businesses is the way in which their customers or patients make payments for the services they receive.” They add, “In contrast to the typical business the typical health care system may have several hundred different contractual relationships with payers which specify different rates of payment for an identical basket of services. The unit of payment is a critical distinction.” (Cleverley & Cameron 2003: 18). Cleverley and Cameron (2003) view the health care organization as the basic provider of health services and recognize it is also a business that depends upon patients and third party payments for funding. The health care organization faces capped costs (McConnell, 2003) and can expect to have its costs continuously scrutinized

(Longest, Rakich, & Darr, 2004; McConnell, 2003).

Legal ownership

Some authors note that organizations can be characterized by their legal ownership type, namely as for- profit, not-for-profit, or government (Gapenski, 2005; Goldsmith, 2005; McConnell,

2003; Showalter, 2004; Sultz & Young, 2006). Authors who mention this characterization seem to recognize doing so has limitations, having primarily a legal, rather than managerial value.

However, Goldsmith (2005) notes that the non-profit organization typically has less clear goals.

McConnell (2003: 23) contrasts the historic development of the health care organization from the simple hospital with its charitable status and unique mission to the modern complex medical

4

center that is challenged by both clinical and business functions, and therefore “…resembles a business.”

Prevalence of professionals and independent contractors

Several authors have cited the increasing professionalization of workers in health care organizations (Kilpatrick & Johnson, 1999; Shortell & Kaluzny, 2000). Fottler (2005) cites health care’s intensive reliance on professionals to deliver services. Shortell and Kaluzny (2000) point out these professionals have an allegiance to their professions. Borkowski (2005: xiii) in a

Preface observes, “There are good books on organizational behavior, but they do not embrace the uniqueness and complexity of the health care industry.” Borkowski (2005: xiii) also cites how health care managers must “…‘manage’ individuals who are not employed by the system, but control 80 percent of the resources used.” Shortell and Kaluzny (2000) observe there exists in the health services organization little organizational or managerial control over the group most responsible for generating work and expenditures. The health services organization, according to

Shortell and Kaluzny (2000), is characterized by dual lines of authority, especially in hospitals, creating role confusion and problems in coordination and accountability. Fottler (2005) observes that health services organizations are quite different from manufacturing organizations in terms of how human resources activities are performed, for example, noting that health service organizations typically emphasize educational credentials.

Summary of Definitions and Characteristics

While there appears to be no universally accepted definition in the literature, components from some definitions form a basis that includes the essential elements of an HSO. Some authors include a wide range of entities in the health care system. Others offer a more precise definition.

The health care organization can be viewed as a basic provider of health care (Cleverley &

Cameron, 2003; Gapenski, 2005: 3) delivering services directly to consumers as a part of a continuum of human services from pre-birth to long term care (Longest, Rikich, & Darr, 2004:

5). While the health care organization must address the functions of management like other organizations (Goldsmith, 2005; Liebler & McConnell, 2004; Longest, et al. 2004; McConnell,

2003), says it has a human service, not a primarily business purpose, (McConnell, 2003) yet faces a competitive and regulated environment (Longest, et al., 2004; McConnell, 2003). Goals are difficult to establish. Outcomes are difficult to measure (Jacobs & Rapoport, 2002; Shortell

& Kaluzny, 2000). High quality is demanded from a variety of stakeholders (Jacobs & Rapoport,

2002; Longest, et al., 2004; McConnell, 2003; Shortell & Kaluzny, 2000). In addition to their unique financial arrangements (Cleverley & Cameron, 2003) health care organizations are characterized by special challenges faced in their intense use of professionals (Borkowski, 2005;

Fottler, 2005; Shortell & Kaluzny, 2000). Having concluded this review of the relevant literature, a discussion of the definition and characteristics of the health care organization follows.

An Operational Definition

An operational definition of a health care or health service organization (HSO) has been constructed by incorporating elements from Longest, et al (2004) and McConnell (2003). The health care or health services organization (HSO) is an entity providing an organizational

5

structure that offers services along a continuum of human services that are primarily intended to provide a substantial support directly to or facilitate a physical or psychological change in an individual.

The inclusion in the definition of the organization’s purpose contrasts it with the typical business organization, which simply produces a product for or delivers a service to an individual for a profit or improving the shareholder wealth. Accordingly, our HSO definition includes organizations in the health care system like hospitals and medical centers, medical practices, nursing homes and assisted living programs, rehabilitation centers, mental health centers, and programs supporting individuals with developmental disabilities programs. Also included are universities, schools, social service agencies, and a myriad of government operations. The definition does not include pharmaceuticals, managed care and insurance providers, medical equipment and supplies companies, and research facilities. While this definition provides a basis for discussing characteristics of the hso and comparing them to other organizations, we want to address the characteristics of the HSO also before determining what a manager needs to know to manage a health services organization.

The Characteristics of the HSO

Characteristics of an HSO by our definition are discussed and compared with characteristics of other organizations.

Services Are Provided to Individuals

This element of the definition is a core feature related to several other characteristics of an HSO.

Given that individual humans are unique, this helps explain the difficulty in determining organizational goals and measuring outcomes. Goals are ambiguous, difficult to identify, observe, quantify, and measure. Determining “best practices” technology is more difficult when the work is labor, not machine, intensive. Best practices or technology is more difficult to apply when the target for change is an individual, not mass producing a product or service. A focus on changing or supporting individuals is a root cause as to why demand for quality is so high.

Stakeholders like families, advocacy groups, and the individuals affected by the service can have an intensely emotional and personal interest in outcomes, not typically found in the business producing goods and services. Rejects in the typical business can be tossed; not so in the HSO.

Complex System of Regulation and Finance

The HSO can be contrasted with the typical business organization in its prevalence of third party payers, such as government or grant funding, or managed care partnerships. The HSO faces challenges not typically experienced by the business organization because the payer is not always the recipient of service. This establishes a triangle of a provider, payer, and recipient of services, whereas a typical business has itself and the customer who pays or arranges its own payment. The rules and regulations accompanying the financing can be far reaching and complex. In the typical business the consumer simply pays the bill directly, or votes with their dollar. On the other hand, the manager in the HSO can be confronted with intense and emotional human conflict when demands from stakeholders like the consumer of a service and the third party payer are not in agreement. The mere mention of government Medicaid and Medicare usually prompts quick understanding of this conflict with administrators, physicians, and either

6

government or private insurers. Any time third party payers are involved, potential conflict is inherent in the system. Avoiding unintentional fraud or abuse in an entangled billing system illustrates this characteristic.

Prevalence of Professionals

Intense use of professionals (Fottler, 2005), allegiances to their profession, and dual lines of management (Shortell and Kaluzny, 2000) typify the human services organization providing a service intended to support or change people. Physicians, nurses, rehabilitation therapists, and counselors are but a few professionals that even if employed directly by the HSO may subscribe to codes of ethics or licensing that come into conflict with organizational goals. As independent contractors these professionals can raise a myriad of legal and supervisory issues.

Other Characteristics

Two other characteristics need comment. First, the operational definition intentionally can apply to all ownership types. While legal ownership was discovered in the literature as a way to categorize organizations, this has limited usefulness for the purposes of determining managers’ needs in today’s health care organization. McConnell’s (2003) description of the history of the modern health care organization, from charitable to a business, suggests ownership or not-forprofit status is less relevant today. Combined with the competitive environment of the industry, any organization, whether it has not-for-profit, for profit, or government status, must be accountable for its finances and outcomes. How an organization is owned may make a difference in how its accounting is done or how non-profit status restricts some activities, but this characteristic reveals little about special challenges for management.

A second characteristic involves the fact the HSO is in an industry noted to be changing and turbulent. Whether this change is greater than or different from what other organizations face is not clear from the literature. However, the likelihood is that managing change is at least as or more important for the health care organization manager as compared to managers in other organizations. This is not identified to be an inherent characteristic in just the health care organization.

A final comment on the operational definition and its relation to the characteristics is needed prior to presenting a model for determining the skills needed by HSO managers. Like any definition, the one proposed here establishes criteria which include some organizations involved in the healthcare industry, but not others. The purpose of this operational definition is not to categorize or classify organizations related to health care or human services, or even to obtain universal acceptance. The operational definition is a basis, along with the characteristics inherent in the HSO, for creating a model that reveals skills managers need.

A Model

The (HSO) is an entity providing an organizational structure that offers services along a continuum of human services that are primarily intended to provide a substantial support directly to or facilitate a physical or psychological change in an individual . (Longest, Rakich, &

Darr, 2004; McConnell, 2003.) Four characteristics compatible with the operational definition have been identified as inherent in the nature of the health care organization. These four

7

characteristics are a focus on individuals, ambiguity in setting goals and difficulty measuring outcomes, complexity in financial arrangements and involvement with third party payers, and a prevalence of professionals and independent contractors.

The model needs one additional definition. A typical business is an entity that has as its primary mission the production of products or delivery of services to generate profit or improve the position or wealth of shareholders or investors. This operational definition is intended like the one for the HSO to be a guide, not a determinant to classify or categorize organizations.

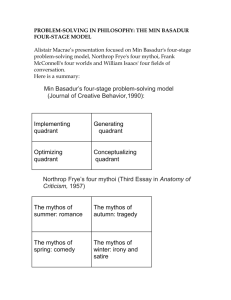

The model incorporates two definitions and four characteristics. An Organizational

Continuum with Health Services Organization positioned on the left and Business located on the right is diagramed in Figure 1. Each of the four characteristics is symbolized by a capital letter.

“I” refers to a focus on individuals. “A” refers to ambiguity in goals and difficulty measuring outcomes. “F” refers to financial complexities and third party payments. “P” refers to professional and independent contractor prevalence. One can plot any organization or group of organizations on the Organizational Continuum. Each of the four capital letters would be placed on the Organizational Continuum line representing where each of the characteristics represented by the symbols would be placed based on where that organization is in terms of whether that characteristic is more or less like the two organizations defined. As an example of its usage the four symbols representing characteristics of a fictitious organization are placed on the

Organizational Continuum in Figure 1.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

FIGURE 1.

Organizational Continuum

I F A P

HSO Business

I = Individual focus

A = Ambiguity of goals and difficulty measuring outcomes

F = Financial complexity and third party payers

P = Professional prevalence and independent contractors

The italicized I, A, F, and P are examples of the placement of these symbols

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Placement of the symbols on the continuum will be facilitated by using the following descriptions of the core differences between the health services organization and the typical business.

8

I = Focus on individuals The more an organization focuses on providing direct supports and services to change individuals and the less it mass produces goods and services, the more it resembles an HSO, the more likely stakeholders are more intense and emotional.

A = Ambiguity of goals and difficulty in measuring outcomes Typically a business has as a real goal a clearly identified profit motive or intent to increase the wealth of the shareholder, or a commitment to ensure a return to an investor. Real goals should not be confused with ones some organizations state publicly, which may make a business sound more like an HSO. The

HSO has conflict and ambiguity regarding service goals versus financial accountability. These conflicts are related to its emphasis on serving or supporting unique individuals and meeting their needs, having the ability to set goals and measure outcomes.

F = Financial complexity and third party payees An organization where the consumer does not pay the bill directly, whether involving insurance companies, governments, or foundations, this is different from the typical business that sets a price for a product or service and accepts payment directly from the consumer. An organization is more like an HSO when there are substantial numbers of complex regulations applicable to it.

P = Prevalence of professionals and independent contractors Organizations with a prevalence of professionals and independent contractors are more like an HSO than a typical business. The existence of clinical staff with allegiances to professions, codes of ethics, and licenses present issues not faced by the typical business without these staff.

Management Skills Needed for the HSO

As an organization tends to be more like a human services organization in any of these four characteristics, specific areas of education, training, and skills are more likely to be an especially significant need, rather than just needed as if it were to be managed like any other organization. The model serves as a guide without built in quantitative benchmarks. Assessment of an organization(s) using the model requires judgment by the user. No single characteristic or group of characteristics automatically prompts a specific type of training. Having one symbol extremely close to the HSO may prompt a need for the special training. Having all or several the symbols moderately close to the HSO on the continuum may also indicate special training is needed. The symbols on the Organizational Continuum line are indicators for action. The characteristics are interrelated, so the indicated training and education tends to overlap.

However, each of four areas of education and training will be described in terms of their applicability to each of the four characteristic in the model. Each training need represents an ability needed by the manager, beyond what would be expected of a manager in a typical business.

Emphasize Strategic Planning

If an organization is identified as having a tendency to being more like an HSO in any one of the four characteristics, a greater emphasis on strategic planning is indicated. Placing a special emphasis on goal setting and focusing on individual outcome measurement can be addressed by identifying a clear vision, mission, and values that sets the stage for clearly written goals. Where there is a prevalence of professionals, financial complexity, and third party payers, involvement in planning from a wide range of stakeholders can facilitate empowerment and goal alignment. Commitment to continuously improving quality is important. Managers can make

9

special efforts to be apprised of “best practices” through benchmarking with other entities and sources.

Cultivate Stakeholders

Managers can create an open environment for professionals and independent contractors, especially where they are more prevalent. Involve financial parties in planning when complex financial arrangements or third party payers are indicated. Know and respect professionals’ allegiances and codes of ethics. Attempt to resolve perceived conflicts arising from them.

Managers can network with advocacy groups.

Address and Manage Conflict

Conflict management and active listening are skills necessary for any organization showing tendencies to being more like an HSO in any of the four characteristics. Any one of the four characteristics has potential for conflict, which while needed for other organizations, the

HSO manager might be prepared to expect more prevalent conflict and more intense and emotional involvement. Conflict can relate to ambiguous goals, measuring outcomes, professional ethics and organization rules, and third party financing, all inherent in the HSO.

Develop an Individual Centered Organizational Culture

Again, where any one of the four characteristics is more like an HSO, this is a needed ability. Knowing what is and how to create or manage an organizational culture that is respected by clinical staff, consumers, advocates, and professionals, funding parties, and regulatory agencies is difficult, but necessary. Skills in strategic planning, conflict management, and stakeholder cultivation overlap this. A commitment to being a steward of the dollar and focusing resources on services is warranted.

Summary, Conclusions, and Implications

An operational definition for a human services organization which includes many health care organizations is available in this paper. Four core characteristics of an HSO were derived from the definition and literature. The definition and core characteristics form the basis for a model that can be used to assess how closely an organization resembles an HSO. The assessment is based on four key characteristics: focus on individuals, ambiguous goals and difficulty in measuring outcomes, complexity in financing and third party payers, and a prevalence of professionals and independent contractors. The education and training indicated to address these characteristics are grouped in four areas: emphasize strategic planning, cultivate stakeholders, manage conflict, and create a human or individual centered organizational culture. Just as the four core characteristics are interrelated, the skill groups to address them overlap.

Managers of human services need the same basic fundamental education and training as other managers. This education includes knowledge of the functions of management like planning, organizing, leading, and controlling along with learning to manage change, etc.

Nothing has been discovered that would indicate this should not be the practice. However, managers now managing or planning to manage organizations whose key characteristics listed in

10

the model resemble the human service organization as defined in the model need additional specialized training. A manager only trained in business or public management principles, but plans a career in organizations that provide direct services to individuals may feel ill equipped to meet the challenges associated with the HSO.

There appears to be no compelling reason to collapse all management training into a unified management department. Since substantial differences were identified in the training needed for an HSO manager relative to the manager of a typical business, there is some justification to offer separate training in the specialized processes. More study is needed on what is needed to manage human services and health care organizations.

References

Borkowski, N. (Ed.). (2005). Organizational behavior in healthcare . Sudbury, MA.: Jones and

Bartlett.

Cleverley, W.O., & Cameron, A.E. (2003). Essentials of healthcare finance (5 th ed.). Sudbury,

MA.: Jones and Bartlett.

Fried, B., Fottler, M.D., & Johnson, J. (Eds.) (2005). Human resources management:

Managing for success (2 nd

ed.). Chicago, IL.: Health Administration Press.

Fottler, M.D. (2005). Strategic human resources management. In Fried, B., Fottler, M.D., &

Johnson, J. (Eds.), Human resources management: Managing for success (2 nd ed.): 1-

24. Chicago, IL.: Health Administration Press.

Gapenski, L., (2005). Healthcare finance: An introduction to accounting and financial management (3 rd

ed.) Chicago, Ill.: Health Administration Press.

Goldsmith, S. (2005). Principles of health care management: Compliance, consumerism, and accountability in the 21 st century .

Sudbury, MA.: Jones and Bartlett.

11

Jacobs, P., & Rapoport, J. (2002). The economics of health and medical care (5 th

ed.). Sudbury,

MA.: Jones and Bartlett.

Kilpatrick, A.O., & Johnson, J.A. (1999). Human resources and organizational behavior .

Chicago, IL.: Health Administration press.

Liebler, J.G., & McConnell, C.R. (2004). Management principles for health professionals (4 th ed.). Sudbury, MA.: Jones and Bartlett.

Longest, B.B., Rakich, J.S., & Darr, K. (2004). Managing health services organizations and systems (4 th

ed.). Baltimore, MD.: Health Professions Press.

McConnell, C. (2003). The effective health care supervisor (5 th

ed.) Sudbury, MA.: Jones and

Bartlett.

Nowicki, M. (2004). The financial management of hospitals and healthcare organizations (3 rd ed.). Chicago, IL.: Health Administration Press.

Santerre, R.E., & Neun, S.P. (2004). Health economics: Theories, insights, and industry studies

(3 rd

ed.). Mason, Ohio: Thomson South-Western.

Shortell, S.M., & Kaluzny, A.D. (2000). Health care management: Organization design and behavior.

(4 th

ed.). Albany, NY.: Thomson Learning.

Showalter, J.S. (2004). The law of healthcare administration (4 th

ed.). Chicago, IL.: Health

Administration Press.

Sultz, H.A., & Young, K.M. (2006). Health care USA: Understanding its organization and delivery (5 th ed.). Sudbury, MA.: Jones and Bartlett.

Wolper, L.F. (2004). Health care administration (4 th

ed.). Sudbury, MA.: Jones and Bartlett.

12

13