Hand-out 3

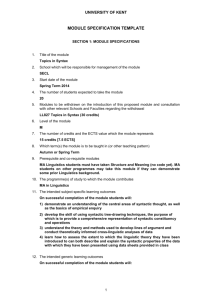

advertisement