Part III

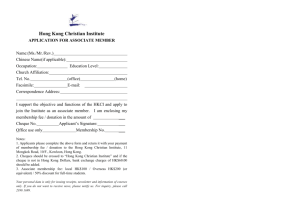

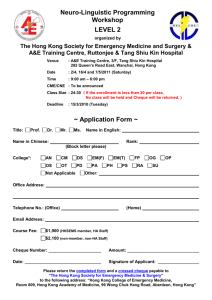

advertisement