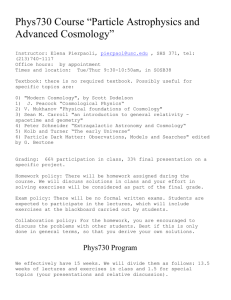

Life and Value: Ecology, Axiology, Soteriology, and Augustine

advertisement

Augustine’s Ecologically Attractive Cosmology Fred Simmons This afternoon I would like to explore the implications of ecology for value theory. Such an undertaking may come as a surprise or seem to betray a mistake. Ecology is not often thought to have implications for value theory, and the suggestion that it could is sometimes believed to reflect either confusion of fact and value or commission of the naturalistic fallacy. Nevertheless I shall argue that at least for those who take Genesis to be scripture, ecology may have implications for value theory, and if so, for soteriology as well. However to make the case for the links I allege between ecology, ethics, and theology it is first necessary to consider the relationship between ecology and cosmology. I. Ecology and Cosmology Ecology and cosmology are both broad and malleable terms, so I’ll start by stating what I mean by each. For my purposes ecology may be understood in its common and basic sense as referring to that branch of natural science that investigates the relationships among organisms and between them and their environment. And as I shall use the term, cosmology denotes theological or philosophical views about the origin, dynamics, and destiny of life, and thereby encompasses life’s environment. Since cosmologies often offer comprehensive descriptions and histories of all reality, they commonly concern the matter, energy, expanse, and duration of the cosmos more directly than the life it has come to support. However, since I am exploring the import of ecology for value theory, that subset of cosmology that pertains to the domain of ecology—namely biological life and its environment—will usually be most relevant. Accordingly though cosmology in my sense may embrace the universe in its entirety since the cosmos as a whole is Simmons 2 ultimately the context of biological life, practically I will be using cosmology here to refer to speculative conceptions of life on this planet and its relatively immediate environment. Since ecology is a natural science and cosmology is a speculative branch of philosophy or theology, they have no necessary connection beyond the fact that any credible cosmology must acknowledge the sorts of dynamics ecologists document and predict. Still, though ecology and cosmology have only this limited necessary connection, they may relate in other ways as well. Specifically, ecology can affect a cosmology’s attractiveness. To appreciate how, let’s consider some of the principal dynamics that ecologists discern, starting with interdependence. Every known form of biological life has proven interdependent. Indeed the interdependence of biological life is so pervasive and diverse that it is clarifying to distinguish two basic types—negative and positive. Negative interdependence refers to the fact that an organism can only survive so long as other organisms or the environment do not destroy it. Negative interdependence is thus a function of organisms’ fragility and is ultimately rooted in their mortality. Positive interdependence, by contrast, indicates the idea that organisms’ homeostatic requirements are only met through other organisms’ positive contributions to them as nutrients or hosts. It is not merely a consequence of fragility, whereby organisms can only survive if not overwhelmed by others, but also victimization wherein an organism can live at all only because it exploits another’s vulnerability to derive the energy and materials that it needs. Further, positive interdependence does not simply attest that organisms may be of use to other organisms when they die so that finite natural systems can renew themselves indefinitely. Beyond Simmons 3 this, positive interdependence denotes the reality that organisms’ death is necessary for the viability of the whole. All of us live, according to ecologists, only because none of us live forever. Evolutionary biology associates mortality with life’s earliest emergence and finds it integral to life’s development and diversification. Mortality is vital for evolution because without it nutrients would not be cycled and life would be static, confined to the forms exemplified by its immortal exemplars. Yet those who are living do not just rely upon others’ deaths but also hasten them. The trophic dynamics that ecologists attempt to quantify and predict menace and dismember the organisms they enable to thrive, for organisms do not only threaten one another but must thwart one another, too. As such the biological capacity, beauty, and complexity made possible by positive interdependence depends upon the vulnerability that renders all organisms negatively interdependent. This pervasive interdependence, where positive senses of interdependence are predicated upon the mortality that make all organisms negatively interdependent, matters to more than species and the individuals that instance them. Ecological systems can adapt, and thus subsist and sustain organisms, because the organisms that these systems support succumb to them. Accordingly, the relationships between species, trophic levels, and the environment that organisms need to flourish also require these organisms’ demise. Such death is not always due to exogenous factors, and sometimes senescence may be its only cause. Nevertheless, even many aged organisms finally die because of infection and hence individuals do not generally live as long as they might. Instead young and old alike are overcome by others endeavoring to extend or increase their own imperiled and fleeting existence, whether visible predators capable of killing their prey in Simmons 4 their prime or invisible interlopers who finish their victims in their weakness. Those that are not taken alive still nourish others by dying as they are decomposed and their nutrients and constituents are recycled through ecological systems. As a result the environment that makes life possible ultimately undoes every individual living thing despite its best efforts and the most propitious circumstances. Each organism—even a climax predator—is alternatively living from and feeding other organisms within the system. Consequently, though biological life is relentlessly prolific, fantastically resourceful, stunningly intricate, and wonderfully multifarious, according to ecologists it is also self-consumptive. I will henceforth refer to these multi-leveled relationships of negative and positive interdependence as ecological dynamics. II. Ecological Dynamics and Cosmology Equally important for cosmology to what ecologists find is when and where they find it, and it turns out that ecological dynamics occur whenever and wherever biological life does. As such, ecologists discern these dynamics before humans appeared and independently of human influence. Accordingly it is attractive to think that non-human nature is subject to ecological dynamics in virtue of its creation rather than as a result of human activity or Divine punishment for it. Hence cosmologies that ascribe ecological dynamics to non-human nature as created are more attractive given ecology than those that attribute these dynamics to non-human nature because of the fall. Though acceptance of basic ecological commitments thus makes it attractive to think that non-human nature is not subject to ecological dynamics because of a human fall, it does not entail this position. Recall my initial insistence that the only necessary relationship between cosmology and ecology is that credible cosmologies acknowledge Simmons 5 the dynamics that ecologists discern. The reason for this restriction is that ecology, as a form of inductive inquiry, cannot properly posit essences. Given this limitation inherent to its methodology, ecology cannot confirm nor contradict the proposition that nonhuman nature fell—or did not fall—into ecological dynamics, for the notion of a fall involves not only how something is now, nor even how it has long and seemingly everywhere been, but what it essentially is. The Christian doctrine of creation, however, as a cosmology, can properly make statements about essences—since it is speculative rather than inductive—and indeed does make such statements—since Christians believe that entities are defined by what God created them to be. Accordingly ecological commitments cannot imply or contradict cosmological claims about the way things were created. Still, though no ecological conclusion can ever be logically incompatible with cosmological statements about essences that accommodate contemporary observations, this does not mean that cosmology and ecology are otherwise completely unrelated. Mere logical consistency is not the only consideration relevant to assessing how well different beliefs cohere, particularly when these beliefs emerge from different domains. Instead some beliefs combine more elegantly, and those worldviews with beliefs that do are more attractive in this sense than those with beliefs that do not. As we have seen, ecology and cosmologies that conceive non-human nature to be created subject to ecological dynamics instance such a comparatively elegant combination, and this is why I called these cosmologies attractive given ecology. Let’s now turn from the relationship between ecology and cosmology with respect to non-human nature to their relationship in the case of human nature. Here the Simmons 6 connection between ecology and cosmology is more complicated but no less relevant. The connection is less direct because, once human implication in ecological dynamics is at issue, humanity’s existence and influence are presupposed. Accordingly ecology’s implications for claims about humanity’s creation cannot follow directly from the presence of ecological dynamics independent of human influence. Instead ecology’s potential bearing on cosmological claims about human nature is mediated by the overwhelming natural continuity between human and non-human nature disclosed by the contemporary life sciences. Specifically, since these sciences show that non-human nature is subject to ecological dynamics before humans appeared and apart from direct human influence, and thereby make attractive those cosmologies that conceive ecological dynamics in non-human nature a function of its creation rather than its denaturing, the overwhelming natural continuity these sciences establish between non-human and human nature makes attractive those cosmologies that conceive human nature to be created subject to ecological dynamics. III. Ecologically Attractive Cosmology and Christianity Though it may be ecologically attractive to think that both human and non-human biological life were created subject to death, decay, and predation, as well as the struggle, stress, and suffering that these realities ineluctably impose on organisms capable of such responses, this sort of cosmology hardly seems compatible with a Christian worldview. After all, Christians commonly deem death a wage of sin and in his letter to the church in Rome Paul influentially contends that creation was subjected to futility and placed in bondage to decay. From a Christian perspective, then, death, decay, and other dimensions of ecological dynamics appear adventitious and aberrant rather than Simmons 7 constitutive of biological life. However since it is attractive given ecology to think that ecological dynamics are a matter of creation rather than the fall, conventionally Christian cosmology turns out not to be ecologically attractive. Upon confronting this conclusion some Christians may decide that ecological attractiveness is not itself very attractive. Many, however, will not. The ecological convictions I have considered are widely known, and they enjoy broad and seemingly irreversible scientific consensus. As such these ecological convictions function as a de facto point of departure for many contemporary people, and thus harbor profound implications for a worldview’s overall attractiveness. To be sure, attractiveness given ecology is not an arbiter of the truth of a cosmology. Still, since many modern people take ecology for granted, such attractiveness now meaningfully affects a cosmology’s credibility. Accordingly the unattractiveness of conventionally Christian cosmology given ecology may trouble many modern Christians. At least it will disappoint those who would rather consistently combine an ecologically attractive and Christian cosmology than have to choose between them or irreconcilably maintain both. Happily I do not think that Christians are forced to face such a choice, for I believe that Augustine’s cosmology is not only Christian but ecologically attractive. However I maintain that Augustine’s cosmology has long been misinterpreted, so this dimension of his worldview has often gone unnoticed. My interpretation of Augustine’s cosmology is thus controversial, but it follows the now dominant scholarly view. Rather than defend that interpretation, though, I want instead to present it, show how it provides an ecologically attractive Christian cosmology, and investigate some of its implications. Simmons 8 The contention that Augustine’s cosmology is ecologically attractive may come as a surprise, for Augustine not only accords great theological significance to the fall but also clearly attributes decline, death, and decay to it. Yet the ecological attractiveness of a cosmology is not merely a matter of whether it propounds a fall or even whether ecological dynamics are its wage, but rather depends upon who is thought to fall and from what state. And it is on these scores that Augustine has often been misunderstood. As many of you undoubtedly know, Augustine believes that human beings fell into ecological dynamics. What is less often appreciated is that Augustine also believes that human beings were created subject to ecological dynamics, including death. Augustine is able to combine these claims by arguing that, while Adam and Eve were yet in their state of original righteousness, God gave them an additional grace that suspended their participation in ecological dynamics. By disobeying God in Eden, however, Adam and Eve forfeited God’s supernatural gift and subjected themselves to ecological dynamics. According to Augustine, then, humans are congenitally mortal and created to participate in ecological dynamics, yet only actualize their mortality and become implicated in ecological relationships because of their fall. Augustine’s cosmology thus ingeniously reconciles the basic Christian conviction that human beings are subject to death and decay because of their fall with the ecologically attractive cosmological contention that biological life—including human beings—is constitutionally enmeshed in ecological dynamics. The result is a meaningfully Christian cosmology that is attractive given ecology. IV. Augustine’s Evaluative Impasse Simmons 9 Since Augustine’s cosmology proves attractive in light of ecology, it turns out to be quite valuable for contemporary Christians. As I noted, attractiveness given ecology affects a worldview’s credibility for many people, and few Christian cosmologies are as attractive as Augustine’s given ecology. Nevertheless, though Augustine’s ecologically attractive cosmology thus resolves a problem for contemporary Christians, it also provokes one for them when combined with some of his other claims. Specifically, Augustine’s cosmology leads to an evaluative impasse for Christians given his judgment that human death is evil. Initially Augustine’s evaluation of human death as evil hardly appears problematic and even seems to make sense. After all, human death is generally a disvalue; it is something we often properly try to avoid or postpone, and mourn when it befalls another. Moreover, we have seen that Augustine follows Christian convention and ascribes human death to sin, and sin is certainly evil. At the same time we have observed that Augustine believes humans to be congenitally mortal, indeed that this contention is precisely what makes his cosmology attractive given ecology. Yet if humans are created mortal and human death is evil, then creation intrinsically harbors evil, something that Christians, including Augustine, have been loathe to allow. Hence the impasse: Christians deny that creation is intrinsically evil yet Augustine considers human death evil and conceives humans to be created mortal. V. How ought Contemporary Christians to Resolve Augustine’s evaluative impasse? Since Augustine’s evaluative impasse emerges from the conjunction of three of his commitments—namely that human death is evil, humans are congenitally mortal, and creation is not intrinsically evil—one of these commitments must be surrendered in order Simmons 10 to resolve it. Yet which commitment ought to go? It is hard to imagine Christians conceiving creation to harbor evil intrinsically. Denying that creation intrinsically harbors evil is one of the ways the faith distinguished itself from some of its principal rivals in the ancient near East and was a difference Augustine tirelessly exploited apologetically. Similarly, principal Christian theological convictions like creation ex nihilo, monotheism, Divine goodness, power, and wisdom, as well as commitment to God’s resounding affirmation of creation, all combine to prevent Christians from being able to ascribe evil to creation. Denying that humans are created subject to ecological dynamics is likewise not an appealing option for many contemporary Christians since doing so forfeits those dimensions of Augustine’s cosmology that make it ecologically attractive. Admittedly a cosmology that is not attractive given ecology may yet be true, and so Christians could deny that humans were created subject to ecological dynamics without having to compromise any of their faith commitments. However since cosmologies that are less attractive given ecology are less credible for many contemporary people, I suspect that many contemporary Christians will be very reluctant to foreswear the claim that humanity was created subject to ecological dynamics. This of course leaves the option of denying that human death is evil, and I think this is the best way for contemporary Christians to resolve Augustine’s evaluative impasse. However there is no good way to deny that human death is evil given Augustine’s terms. Augustine espouses a binary value theory, by which I mean that Augustine recognizes only two values, namely good and evil. Confined to these evaluative options, Augustine is consigned to evaluate human death as evil so long as it is Simmons 11 accorded a value and is not believed to be good. As I have already noted, powerful intuitions and experience suggest that human death is not without value, and that it is generally not good. Instead any credible value theory is bound to deem human death, considered generally and in and of itself, a disvalue. As a result, proponents of Augustine’s binary value theory can only reasonably regard human death as an evil. Christians who endorse Augustine’s ecologically attractive cosmology thus need to have it both ways with human death evaluatively—as at once a disvalue but not an evil. Though such a seemingly contrary combination may appear legerdemain, it is not entirely unprecedented and can be legitimate. Augustine’s ingenious cosmology allowed him to have it both ways with human death descriptively—as at once a feature of creation and a wage of sin—and yielded an account of creation both ecologically attractive and Christian. Yet Augustine’s binary value theory does not allow human death, or anything else, to be evaluated as both a disvalue and not an evil since it defines all disvalue as evil. Accordingly in order to assign human death a value other than evil without affirming it to be good, Augustine’s binary value theory must be abandoned. Specifically there must be some category of disvalue that is qualitatively different from evil. I propose to distinguish that sort of disvalue by denominating it bad and in so doing supplant Augustine’s binary value theory with one that is tripartite. I define the values in this tripartite value theory as follows: good denotes that which conduces to or is constitutive of an individual’s flourishing; bad refers to hindrances to an individual’s flourishing that are necessary so that other individuals may flourish given ecological dynamics, and evil describes hindrances to an individual’s flourishing that others’ flourishing does not require. My value theory thus evaluates Simmons 12 hindrances to an individual’s flourishing as a disvalue, and qualitatively distinguishes between the value of those hindrances that are required for the continued viability of the systems that sustain biological life as we know it, and those that are not. For example, I evaluate death due to senescence as bad and murder as evil. Both end the individual’s life, and are therefore a disvalue, all things being equal, but because they happen for fundamentally different reasons and evoke starkly different responses, I believe they are properly evaluated in qualitatively different ways. VI. Tripartite Value Theory not an Ad Hoc Solution The value theory I propose resolves Augustine’s evaluative impasse by allowing human death to be assessed as a non-evil form of disvalue. Given this evaluative option creation per se could remain free of evil as Christians insist even if human beings were created mortal as Augustine’s ecologically attractive cosmology claims because human death may merely be bad. Yet though my tripartite value theory is just what is needed to eliminate Augustine’s evaluative impasse without abandoning commitments that are valuable to many contemporary Christians, it is not simply an ad hoc solution, either on Augustine’s terms or from a Christian perspective more generally. Let’s begin by considering tripartite value theory on Augustine’s terms. As I have explained, a tripartite value theory accommodates and indeed elucidates the dual status that human death has for Augustine as at once a facet of creation and a consequence of sin. A tripartite value theory also correlates well with Augustine’s cosmology more broadly. For example, the value theory that I propose marks the consequences of forfeiting God’s supernatural gifts as one sort of disvalue and evaluates humanity’s destructive responses to that disvalue as disvalue of another sort. Specifically, the death, Simmons 13 decay, discomfort, fatigue, and struggle for subsistence that characterize human life after Eden for Augustine perfectly illustrate the normative content I ascribe to bad, while the murder, envy, deception, and arrogance recounted in Genesis’ primeval history exactly instance the normative content I attribute to evil. Thus just as Augustine’s cosmology distinguishes between creation, Eden, and the fall descriptively, the value theory that I propose distinguishes between these stages evaluatively by associating different kinds of value with each of them. Though non-Augustinian Christians may not confront Augustine’s evaluative impasse, they ought not to dismiss this sort of value theory as an ad hoc expedient either, for tripartite normativity effectively synthesizes prominent Christian meta-ethical trajectories. Recall that the only Biblical accounts of creation not issued in a soteriological context—namely those found in the wisdom literature—depict creation as intrinsically bivalent. Next, observe that Christians consistently distinguish between creation and sin. Couple the claims that creation is intrinsically bivalent and distinct from sin, and a tripartite value theory appears. Admittedly those Christians for whom the wisdom literature is marginal may not be accustomed to conceiving creation as intrinsically bivalent. However ascription of bivalence to creation need not be resisted as a form of dualism at odds with central Christian commitments. In the context of an ecologically attractive cosmology and a value theory appropriate to it, bivalence describes the bi-conditional relationship between value and disvalue that reflects the cyclical dynamics of a self-renewing yet selfconsumptive finite process in which one organism’s development requires another’s decay as nutrients are cycled and energy is transferred. In such cases calling creation Simmons 14 bivalent is an evaluative claim, not a metaphysical or cosmological contention, and it is thus neither Manichean nor Gnostic. Accordingly just as my tripartite value theory is not merely expedient, the bivalent interpretation of creation that it brings given an ecologically attractive cosmology is not at all heretical. VII. Objection: Christians believe Creation is not just Not Evil, but Good Yet even if the value theory I propose is neither a heresy nor an ad hoc solution to Augustine’s evaluative impasse, tripartite value theory’s congruity with other principal Christian evaluative commitments may still seem dubious. In particular, though this tripartite normativity allows Christians to endorse Augustine’s ecologically attractive cosmology without forfeiting the claim that creation is not intrinsically evil, its insistence upon creation’s implicit bivalence appears to force Christians to foreswear the grand, repeated, affirmations in Genesis’ initial chapters that God declared everything God had made to be good, indeed, finally, very good. I respond to this worry by noting that the Priestly account that records these acclamations describes creation at the level of kinds rather than individuals, and that it is creation as a whole that God there judges to be very good. The level of creation that the Priestly account treats is significant, for the value theory I propose only depicts an ecologically ordered creation to be bivalent for individuals, not for kinds or as a whole. According to my tripartite normativity species, ecosystems, and still greater wholes are simply good given ecological dynamics since these sorts of creations persist and thrive— precisely what my value theory defines as good—even though the individual organisms that instance and compose them die and decay. In fact, given extant ecological exigencies, species and ecosystems function and flourish only because the individuals Simmons 15 they support flourish, but then decline, die, and decay. As such bivalence for individuals does not contravene or otherwise threaten the goodness of creation as a whole but is instead necessary for it so long as ecological dynamics obtain and biological life is valorized. The Priestly acclamation of creation is thus not simply consistent with the connection between good and bad that my values attribute to creation as conceived by ecologically attractive cosmology but depends upon that connection. VIII. From Evaluative Impasse to Soteriological Puzzle Although the realization that the goodness of an ecologically ordered whole depends upon bivalence for individuals resolves the question of how these differing Christian assessments of creation could cohere, it also provokes a puzzle of its own. Specifically, much conventional Christian soteriology has depicted salvation as delivering human individuals from all disvalue. However, since Christians who endorse an ecologically attractive cosmology believe that God created a world structured and sustained by ecological dynamics, they are also committed to believe that God created all biological individuals to be subject to bivalence. Creation is no neutral notion for Christians, for as we have seen Christians affirm God’s acclamation of creation and assert God’s wisdom, power, goodness, and freedom from all constraint. Yet if Christian advocates of ecologically attractive cosmology believe that such a God created and celebrated ecological dynamics and their disvalues, is it appropriate for them to believe that this God would choose to save God’s living creatures from these dynamics and disvalues as conventional Christian soteriology claims? IX. Soteriological Opportunities Afforded by my Proposed Value Theory Simmons 16 To explore this question I begin with the assumption that Christians believe salvation will deliver from evil. Given this belief, Christians are constrained to conceive salvation to deliver from all disvalue whenever they adopt a binary value theory, for according to such a value theory all disvalue is evil. And indeed I have observed that conventional Christian soteriologies, informed as they are by binary value theories, typically depict salvation as delivering from all struggle, stress, and frustration; all decline, death, and decay, in short from all disvalue, whether due to ecological dynamics or sin. For those who adopt a tripartite value theory’s qualitative distinction between disvalues, by contrast, delivery from evil need not imply release from all disvalue. Instead, tripartite value theory makes it conceptually possible for salvation to deliver form sin and its consequences, as Christian soteriology requires, without rescuing from the bad that is endemic to creation for individuals given an ecologically attractive cosmology and a value theory appropriate to it. X. Should Christians Exercise the Soteriological Alternatives Afforded by this Tripartite Value Theory? Recognizing how tripartite value theory’s qualitative distinction between disvalues makes alternatives to conventional Christian soteriology conceptually possible is straightforward. Determining whether Christians committed to an ecologically attractive cosmology like Augustine’s ought to prefer one of these alternatives to conventional soteriology, however, is not. Soteriological expectations depend upon many factors, and my discussion thus far underdetermines judgments about which conceptions of salvation would be more appropriate. Tripartite value theory may be the only viable way for Christians who espouse an ecologically attractive cosmology to avoid Augustine’s evaluative impasse, but neither tripartite value theory nor an ecologically Simmons 17 attractive cosmology, or even their conjunction require rejection of conventional soteriology. Yet even if the considerations I have adduced thus far do not decide this soteriological question, they can be germane to its resolution. Accordingly, rather than presume to specify the sort of soteriology that Christian advocates of ecologically attractive cosmology and tripartite value theory should adopt, I will explore some of the influences that these cosmological and evaluative commitments could exert on conceptions of salvation. I will then close by adumbrating a few thoughts about the difference that exercising one of the soteriological alternatives afforded by tripartite value theory would make to conceptions of the Christian life and the role of ethics therein. Upon considering the influence that ideas about creation and value could exert on conceptions of salvation, it is important to begin by reiterating that those who endorse Augustine’s cosmology and the value theory I propose need not embrace the novel soteriological options that tripartite normativity provides. Neither ecologically attractive cosmology nor qualitative distinction between bad and evil entail a soteriology that depicts salvation as occurring amidst disvalue. Nevertheless, reflecting on the potential that doctrines of creation and value theory have to influence the perceived propriety of different understandings of salvation remains relevant because an ecologically attractive cosmology and a tripartite value theory are not common Christian commitments, and they may affect how suitable a given sort of soteriology seems. Specifically, in the context of basic Christian theological commitments, ecologically attractive cosmology would mean that the God who would save is the God who, without constraints of knowledge, power, goodness, or materials, created human individuals to be subject to ecological dynamics and their bivalence for them. Further, Simmons 18 we have seen that God’s resounding acclamation of creation as very good suggests God’s approval of the world that God created, which, given an ecologically attractive cosmology, includes human individuals’ subjection to bivalence. Finally, given a tripartite value theory, it is conceptually possible for humans to be saved from sin while yet enmeshed in the bivalence of ecological dynamics. So, granted an ecologically attractive cosmology it seems strange to think that God would save human individuals from the disvalue God created and celebrated, and given a tripartite value theory God need not save human individuals from the disvalues endemic to ecological dynamics in order to deliver them from sin. Taken together I think these considerations provide good—though not decisive—reasons for Christians who adopt an ecologically attractive cosmology and a tripartite value theory to ponder soteriologies that conceive salvation to deliver from evil but not to rescue from the disvalues that ecologically ordered systems must impose upon the individuals they sustain if these systems are to subsist. XI. The Difference this sort of Soteriology would Make Yet since an ecologically attractive cosmology and a value theory appropriate to it neither necessitate such a soteriology nor provide conclusive reasons to adopt it, I shall conclude my remarks not by urging this sort of soteriology’s adoption but instead by considering some dimensions of the difference that conceiving of salvation to occur amidst ecological dynamics would make to Christian ethics and theology more broadly. Given an ecologically attractive cosmology and God’s acclamation of creation, the interdependence implicit to ecological relationships would not simply be ubiquitous but also normative for all biological life. Human individuals would then depend upon other life and other life would depend upon us not only because we can help and hinder each Simmons 19 other but because God created all biological life to live from and for others. On such a scheme serving others to the point of laying down one’s life for them would not be merely an infralapsarian ethic, necessary as a response to sin, but rather a realization of the life for which we were created. More concretely, while it is surely the case that Jesus’ life and teaching of service to others only led to death on a cross because of sin, neither his life of service nor its culmination in death should be ascribed to sin once ecological dynamics and the interdependence that they structure are conceived as normative for biological creation. Instead so long as ecological dynamics obtain, every organism will give up its life as a ransom for many. Though Jesus’ passion would thus prefigure our common destiny, it would still remain distinctive since Jesus gave up his life for others consciously and in voluntary obedience to God. Given an ecologically attractive cosmology, Christians would believe that we are all created to give up our lives for others; such a sacrifice would be our lot, whether we willingly comply with it or not. However since we are also called to give up our lives for others, at issue is not simply whether we will do so, but whether we will to do so. On such an interpretation the Christian life itself, that communal endeavor to do God’s will by being disposed—among other things—to love others to the point of dying for them, emerges as one way to answer God’s call deliberately and thereby become the sort of creature that God created us to be. Thus appropriating our ecological role, Christians would intentionally fulfill God’s will for human beings and become more witting participants in Divine providence. Conceived in this way, the Christian life can no longer be construed as a means to a reward different from it, as something to be transcended once sin is overcome or someone is saved. Instead the Christian life appears Simmons 20 as precisely what the gospels repeatedly portray Jesus to claim it to be, namely the way that human beings participate in the good news that is the coming of the kingdom—that realm where God’s will is willingly done by God’s creatures. Given an ecologically attractive cosmology and God’s acclamation of creation, Christians will believe that biological life is created to live from others’ sacrifices and to sacrifice itself for others. As such when human beings will to follow Jesus’ example, they self consciously embrace the life God created them to have and in so doing actualize God’s kingdom. With conventionally Christian cosmology, in which ecological dynamics are conceived to be aberrant and punitive, voluntary embrace of the self-sacrifice that they enjoin and Jesus commanded only seems salvific if a means to something quite different. And indeed, much conventional Christian soteriology depicts salvation as a realm of such rapture that all disvalue is left behind. The Christian life may conduce to this sort of salvation but can hardly be constitutive of it, for individuals’ implication in disvalue persists so long as they are involved in ecological dynamics. If, however, God created human beings and the rest of biological life to be subject to ecological dynamics, Christians can understand Jesus’ call to discipleship as a salvific obligation not because it promises a way to be delivered from these dynamics but because it indicates the particularly human way that God would have us participate in them. Given an ecologically attractive cosmology and a value theory appropriate to it, the Christian life need no longer appear as a novel, counter-intuitive means to all too typical human ends. Instead Christian discipleship may be understood to foster a distinctive community precisely because it seeks to transform those all too typical human ends as well as those who would pursue them.