ARC-04-3162 - Adegbe..

advertisement

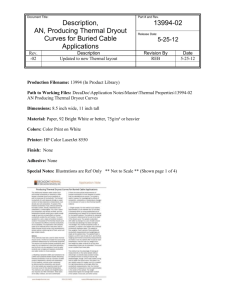

An Assignment on Arc 810 (APPLIED CLIMATOLOGY) GUIDELINES FOR DESIGN WITH CLIMATE IN THE SAVANNAH ZONE OF NIGERIA (Implications for prototype mass housing) By ADEGBENRO OLALEKAN O. (Arc/04/3162) Submitted to THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE, FEDERAL UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY AKURE. COURSE LECTURER Prof. Ogunsote AUGUST, 2011 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT 1.0 INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………… 2.0 STUDY AREA 3.0 CLIMATE IN THE SAVANNAH ZONE 4.0 DESIGN GUIDELINES IN THE SAVANNAH ZONE 5.0 …………………………………………………………… …………………………………….. …….………………. …………………………….. 4.1 Building Configuration and Orientation 4.2 Openings 4.3 Building Materials ……………………………………………………. 4.4 Outdoor Spaces …………………………………………………….. ……………………………………………………………. RECOMMENDATIONS AND CONCLUSION REFERENCES 2 …………………………….. Abstract The habitant bill of rights, defined the qualitative issues connected with design of houses and their groupings into new communities as a supplement to other codes and regulations which have attempted to define qualitative issues relating to the building industry. In the northern part of Nigeria, which houses the savannah zone have evidences of low quality in design and planning of houses, relative to environmental influences, like weather and regular seasons. The zone covers a large portion of the country and consists of towns like Sokoto, Yelwa, Kano, Gusau, Maiduguri, Yola, Ibi, Potiskum, Minna, Bida, Abuja, Zaria, etc. It has been observed that the weather condition in this part of the country is prone to dry and hot climate from early February to June. This period gives residents in the area a perpetual experience of living amid extreme dryness and exhaustive heat as from midday to midnight throughout the period. It needs therefore the refreshing coolness of people’s habitat and surroundings. From the end of June to September, the weather is fairly good with intermittent rains and showers sometimes accompanied by strong winds and storms. In early October, when the heat varies, powdered dust particles are brought from Sahara by the harmattan winds. The harmattan period extends as far as January when an ambient temperature within the interior could go as low as between 8 and 10oc thereby requiring heat. From the observations, it’s clear that the inhabitants of this area are faced with problems of designing and constructing suitable houses that will cope with these varying climatic conditions, such that the minimum hardship is suffered during both the hot and harmattan periods while employing minimal mechanical cooling and heating devices respectively. The aim of this study is to provide a design guideline putting the climate of the savannah zone into consideration which will provide adequate comfort for the inhabitants of such area and can be adopted as prototype for mass housing scheme in the area which involves the use of different kinds of building materials, building orientation, spacing, types and sizes of openings, etc. Keywords: Climate, Savannah Zone, Thermal Comfort, Discomfort, Openings. 3 1.0 INTRODUCTION The primary function of all buildings is to adapt to the prevailing climate and provide an internal and external environment that is comfortable and conducive to the occupants. However, in this era of climate change and global warming, providing comfort for the occupants of a building is quite challenging and very fundamental. This is as a result of growing ranges of challenges now facing designers to provide buildings that will be fit and comfortable (Akande, 2010). The need to design with climate has always been a major consideration in architecture. Vitruvius, in his Ten Books on Architecture drew attention to the importance of climate in architecture and town planning. Climate in a narrow sense is usually defined as the “average weather”, or more rigorously, as the statistical description in terms of the mean and variability of relevant quantities over a period ranging from months to thousands or millions of years (Wikipedia). The classical period is 30 years, as defined by the world metrological Organisation (WMO). These quantities are most often surface variables such as temperature, precipitation, and wind. Architectural design is defined by boundary because of the variation of climatic zones. There are six zones that have been defined for Nigeria: the coastal Zone, the forest zone, the transitional zone, the savanna zone, the highland zone and the semi-desert zone, but for the purpose of this study, we are going to base only on the savannah zone which covers majorly the northern part of the country (Yelwa, Sokoto, Gusau, Kano, Maiduguri, Yola, Ibi, Potiskum, Minna, Bida, Abuja, Zaria). There are design guide lines that are common to all these zones, if all these are observed, then all the architectural design will adapt to their environment. Architectural design should enable the occupant of the building to achieve thermal comfort. Thermal comfort basically has to do with the temperature that the resident considers as comfortable to stay in. Indoor thermal comfort is achieved when occupants are able to pursue without any hindrance, activities for which the building is intended. Hence, it is essential for occupants well being, productivity and efficiency. This paper takes a look into the climatic condition of the savannah region of the country Nigeria and sees how Architecture can be incorporated into the designing of buildings that will give the inhabitants thermal comfort and on the long run could be used as a prototype for the designing of subsequent buildings in the area. 4 2.0 STUDY AREA The study area selected for the purpose of this paper is the savannah zone of the country, which is majorly found in the northern part of Nigeria. The savannah zone is the only zone that has the highest number of cities and towns it covers and is predominantly known for its hot-dry climate, which the makes the weather harsh for the inhabitants of such area. some of the towns covered by the savannah zone include; Sokoto, Yelwa, Kano, Gusau, Maiduguri, Yola, Ibi, Potiskum, Minna, Bida, Abuja, Zaria, Bauchi and so on. Map of Nigeria showing the towns in the savannah zone 5 3.0 CLIMATE IN THE SAVANNAH ZONE It has been observed that the weather condition in this part of the country is prone to dry and hot climate from early February to June. This period gives residents in the area a perpetual experience of living amid extreme dryness and exhaustive heat as from midday to midnight throughout the period. It needs therefore the refreshing coolness of people’s habitat and surroundings. From the end of June to September, the weather is fairly good with intermittent rains and showers sometimes accompanied by strong winds and storms. In early October, when the heat varies, powdered dust particles are brought from Sahara by the harmattan winds. The harmattan period extends as far as January when an ambient temperature within the interior could go as low as between 8oc and 10oc thereby requiring heat. Cold nights and hot days alternate for six to ten months of the year. This usually accelerated during the harmattan period where the ambient temperature within the inside of the building could go down as low as between 8oc and 10oc. In this case, thermal storage is needed in keeping the interior cool in the day and providing warmth at night. Climatic Variation in the Northern Climatic Zone (Savannah Area) Zones Northern Seasons Air temperature Day Night oC oC Humidity % Hot Dry (Nov/Dec to April/May) 32-43 15-27 20-55 Warm Humid (May/June to Sept) 27-32 24-27 55-95 Cool Dry (Sept/Oct to Nov) 18-27 4-15 20-55 Annual Rainfall (mm) Wind (km) 1-10 500-1300 1-10 Nigeria Source: National Universities Commission (1977). Standard Guide for Universities 6 1-10 4.0 DESIGN GUIDELINES IN THE SAVANNAH ZONE There are some design guidelines that can be put into use by the designer in achieving a thermal comfort for the inhabitants of the Savannah zone. Buildings are designed and built to provide shelter for man and protect man from harsh weather conditions and achieving the maximum thermal comfort for the occupant. In the savannah zone, the kind of climate in existence should be put into maximum consideration, because it determines the kind of design and materials to be used and also the orientation of the structure as well. The following classifications will help in carrying out a good design in this zone and can therefore be adopted as a prototype for prospective building designs which might be in form of mass housing. 4.1 Building configuration and Orientation This refers to the method or way in which the building with its environment is going to be catered for or arranged. It also refers to the configurations in the design and how the spaces are to be arranged. It comprises of the orientation of the building in respect to the sun and also the prevailing wind. In hot-dry climate regions, it is desirable to lower the rate of temperature rise of the interior during day time in summer. To achieve this, the building should preferably be compact. The surface area of its external envelope should be as small as possible, to minimize the heat flow into the building. The ratio of the building envelope’s surface area to its volume or ratio of floor area to its volume determines the relative exposure of the building to solar radiation. The best layout is that of a patio or a courtyard surrounded by walls and thus partially isolated from the full impact of the outdoor air. This configuration is very common in hot-dry climate. The surface of the buildings must be protected from excessive solar gains from the sun, by having an orientation placing their long axis east – west, that is, the longer sides of the building should face the north and south direction. For the purpose of ventilation, there is the need to have open spaces in the building area and such spaces must be protected against hot and cold winds. The spaces allocated as rooms should be single banked, that is, there must be a direct flow of air through the building from one side to the other without any wall barrier. This therefore means that permanent provision should be made for constant air movement in and out of the building. 7 Spacing of buildings with openings serving as courtyards 4.2 Openings Openings refer to different open able areas in the building. They include the windows and also the doors. For the purpose of this study, we are going to base it only on windows being the openings in the building. Due to the climatic condition of the savannah zone, the kind of openings that will be used will be quite different from the other zones with different climatic analysis. The savannah zone being a hot and dry zone will require the use of composite windows which are to occupy between 20% to 35% of the wall area. These openings should be able to catch the breeze and improve body cooling. This will make the interior of the building comfortable for the occupant. Permanently open ventilation vents should be introduced to allow for permanent ventilation throughout the year. These openings must be protected against sun and rain during hot sunny periods and heavy downpours. The use of sun-shading devices can help in reducing the amount of sunlight entering into the interior and thereby help in maintaining normal comfort in the building. Roof overhangs of adequate sizes and geometry can help in reducing the driving force of rain from entering through the window into the building. 8 Shading of openings from sunlight and rain 4.3 Building materials Building materials affect the kind of thermal comfort that the occupant of the building will experience. Due to the kind of climate in the savannah zone, and the necessity to reduce the rate of gain of heat energy into the building during the day, and the desire to keep the inside of the building warm at night when the temperature drops, the use of heavy weight materials should be used in the construction of such buildings. Such materials should be with high thermal capacity and having a time lag of over 8 hours. The kind of materials that can be used for flooring, roofing and walls should possess high thermal capacity or the ability to store heat and there by delay or reduce the flow through the material into the inner part of the building. With the time lag of over 8 hours, from when the sun is at its maximum brightness (2pm) to about 10 pm in the night, is when the heat stored in the building will find its way into the interior of the building, thereby keeping it warm and comfortable for the occupant. Examples of such materials include stone masonry, well compacted mud, bricks, RCC slab covered with insulation materials for roofing, timber or wood, etc. 9 Brick wall with good thermal storage 4.4 Outdoor Spaces These spaces refer to outdoor openings which might be in form of courtyards and also verandahs or balconies. These spaces should be well shaded from intense sunlight and heat, and also from the driving force of rain. It is advisable and better to have the outdoor spaces incorporated into the building which can sometimes serve as an outdoor sleeping area in times of intense heat at night. Open spaces have to be seen in conjunction with the built form. Together they can allow for free air movement and increased heat loss or gain. Open spaces in any complex are inevitable. The question is how should they be and how much should there be? After all, any built mass modifies the microclimate. An open area, especially a large one allows more of the natural climate of the place to prevail. Open spaces gain heat during the day. If the ground is hard and building surfaces are dark in colour, then much of radiation is reflected and absorbed by the surrounding buildings. If however, the ground is soft and green, then less heat is reflected. In hot-dry climates, compact planning with little or no open spaces would minimize both heat gain as well as heat loss. When the heat production of the buildings is low, compact planning minimizes heat gain and is desirable. This is how traditional settlements often are. Principle of the courtyard: Due to the incident solar radiation in the courtyard, the air in the courtyard becomes warmer and rises up. To replace it, cool air from the ground level flows 10 through the openings of the room, thus producing the air flow. During the night, the process is reversed. The cooled surface air of the roof sinks down to the court and this cooled air enter the living spaces through the low level openings and leaves through higher level openings. This system can work effectively in hot and dry climates, where day time ventilation is undesirable, as it brings heat inside and at night the air temperature becomes cooler. A courtyard with water fountain at the middle The best way to keep the courtyard shaded and partially open to the sky 11 5.0 RECOMMENDATIONS AND CONCLUSION Climate should be the most important factor considered by an architect when designing a building. Architectural design is meant to solve the problem of shelter and shelter is meant to protect from harsh weather, dangers (wild animals, thieves) and harsh climatic conditions. Therefore, architectural design should be made in view of weather or climate. In the final analysis, it realized that architects should study the climate of region (savannah) and design should made to conform to the climate (i.e.) it should be habitable and comfort should be achieved despite the climate. Also, materials recommended for construction of architectural design in the Zone should be adhered to and should be that which is favorable with the climate condition present where it is suppose to be constructed. Importation of architectural designs from overseas is not appropriate because of the variation in the climatic conditions existing in both area, therefore appropriate consultation should be carried out in the region to understand the kind of weather or climate that exist in that region before architectural design is commenced. Following conclusions are drawn from the study presented herein with respect to Architectural design in hot-dry climate of the savannah zone: i. To minimize energy demand and provide better degree of natural conditioning, it is essential to give climatic considerations for designing of residential buildings. ii. For a building to function in co-ordination with the environment there should be a relation between the interior and exterior environment, orientation, building form, materials etc. iii. Orientation of the overall built form should be in co-ordination with the orientation of the sun and prevailing wind direction. iv. Rectangular form of the building should be elongated along east-west direction, i.e., the orientation of the building should be north-south. 12 v. When buffer spaces are provided between exterior and interior spaces, heat from outside dissipates before entering interiors. Non-habitable rooms such as toilets, stores and galleries can be provided as heat barriers in the worst orientations on the outer periphery of the building. vi. Provision of a central courtyard is preferable which helps in achieving shaded spaces, natural light in most of the places and better circulation of air without providing many openings on the exteriors surfaces. However, provision of courtyard is effective only if it has a plan area and volume relationship proportional to built-up area and its volume. vii. Thick walls create thermal time-lag, thus creating comfortable conditions. viii. As the position of a window goes higher, light penetration increases with lesser heat gain. 13 REFERENCES Agarwal, K.N., Thermal data of building fabric and its application in building design, Building Digest, No. 52, June 1967, CBRI, Roorkee, India. Akande, K. O.,Indoor Thermal Comfort for Residential Buildings in Hot-Dry Climate of Nigeria, proceedings of conference: Adapting to Change: New thinking on Comfort, Cumberland Lodge, Windsor, UK, 9-11 April 2010, London. Anderson, B., Solar Energy Fundamentals in Building Design–Total Environment Action, McGraw-Hill Book Co., 1977. Arorin, J. E. (1953). Architecture and Climate. Reinhold Publishing Corp., New York. Evans, M. (1980). Housing, Climate and Comfort. The Architectural Press, London. Krishan, A., Climate Responsive Architecture–A Design Handbook for Energy Efficient Buildings. Tata McGraw-Hill Pub. Co. Ltd., New Delhi, 2000. Krishan, A. and Agnihotri, M.R., Bio-climatic architecture – a fundamental approach to design, Architecture+Design, Vol. 9, No. 3, May-June, 1992. Nicol, J.F. and Humphreys, M.A. (2004), Adaptive Thermal Comfort and Sustainable Thermal Standards for Buildings. In the Proceedings of Moving Thermal Comfort Standard pp 150-165. Ogunsote, O. O. (1990a).Architectural Design with Nigerian climatic condition in view: A Systems Approach. Rao, K.R. and Prakash C., Thermal performance rating and classification of walls in hot climate. Building Digest, No. 101, October 1972, CBRI, Roorkee, India. Straaten, V.J.F., Thermal Performance of Buildings. Elsevier Pub. Co., Amsterdam, 1967. 14