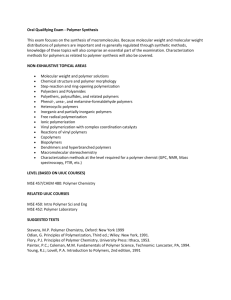

History Of Natural And Synthetic Polymers

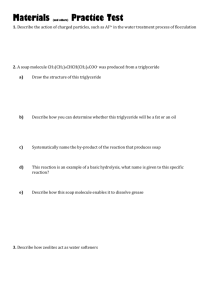

advertisement

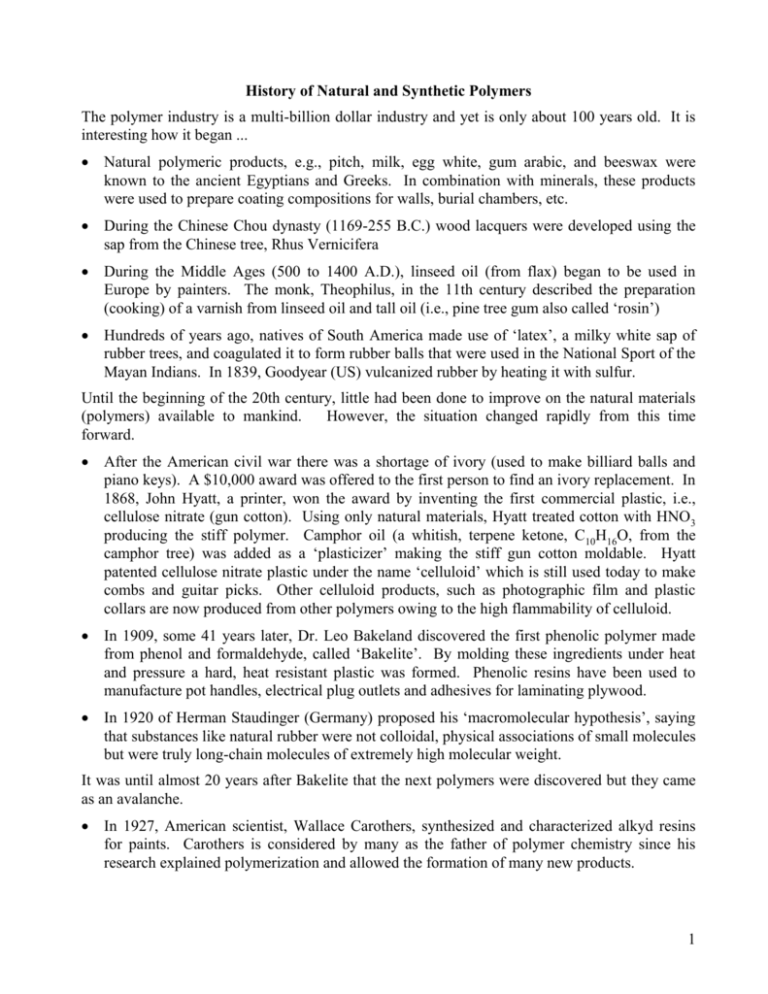

History of Natural and Synthetic Polymers

The polymer industry is a multi-billion dollar industry and yet is only about 100 years old. It is

interesting how it began ...

Natural polymeric products, e.g., pitch, milk, egg white, gum arabic, and beeswax were

known to the ancient Egyptians and Greeks. In combination with minerals, these products

were used to prepare coating compositions for walls, burial chambers, etc.

During the Chinese Chou dynasty (1169-255 B.C.) wood lacquers were developed using the

sap from the Chinese tree, Rhus Vernicifera

During the Middle Ages (500 to 1400 A.D.), linseed oil (from flax) began to be used in

Europe by painters. The monk, Theophilus, in the 11th century described the preparation

(cooking) of a varnish from linseed oil and tall oil (i.e., pine tree gum also called ‘rosin’)

Hundreds of years ago, natives of South America made use of ‘latex’, a milky white sap of

rubber trees, and coagulated it to form rubber balls that were used in the National Sport of the

Mayan Indians. In 1839, Goodyear (US) vulcanized rubber by heating it with sulfur.

Until the beginning of the 20th century, little had been done to improve on the natural materials

(polymers) available to mankind.

However, the situation changed rapidly from this time

forward.

After the American civil war there was a shortage of ivory (used to make billiard balls and

piano keys). A $10,000 award was offered to the first person to find an ivory replacement. In

1868, John Hyatt, a printer, won the award by inventing the first commercial plastic, i.e.,

cellulose nitrate (gun cotton). Using only natural materials, Hyatt treated cotton with HNO3

producing the stiff polymer. Camphor oil (a whitish, terpene ketone, C10H16O, from the

camphor tree) was added as a ‘plasticizer’ making the stiff gun cotton moldable. Hyatt

patented cellulose nitrate plastic under the name ‘celluloid’ which is still used today to make

combs and guitar picks. Other celluloid products, such as photographic film and plastic

collars are now produced from other polymers owing to the high flammability of celluloid.

In 1909, some 41 years later, Dr. Leo Bakeland discovered the first phenolic polymer made

from phenol and formaldehyde, called ‘Bakelite’. By molding these ingredients under heat

and pressure a hard, heat resistant plastic was formed. Phenolic resins have been used to

manufacture pot handles, electrical plug outlets and adhesives for laminating plywood.

In 1920 of Herman Staudinger (Germany) proposed his ‘macromolecular hypothesis’, saying

that substances like natural rubber were not colloidal, physical associations of small molecules

but were truly long-chain molecules of extremely high molecular weight.

It was until almost 20 years after Bakelite that the next polymers were discovered but they came

as an avalanche.

In 1927, American scientist, Wallace Carothers, synthesized and characterized alkyd resins

for paints. Carothers is considered by many as the father of polymer chemistry since his

research explained polymerization and allowed the formation of many new products.

1

Following is a chronology of important developments in polymer science ...

Name of Polymer

Applications

1868 Hyatt (US) celluloid

1909 phenol-formaldehyde (Bakelite)

1920 cellulose nitrate lacquers for autos

1927 Carothers produced alkyd resins

1927 poly(vinyl chloride),

cellulose acetate plastics

1929 polysulfide (Thiokol) rubber,

urea-formaldehyde resins

1931 poly(methyl methacrylate) plastics

Neoprene synthetic rubber

1936 poly(vinyl acetate) and

poly(vinyl butral)

1937 polystyrene (PS),

styrene-butadiene (SBR)

1938 Carothers produced nylon 66 fibers

1939 melamine-formaldehyde resins,

poly(vinylidene chloride)

1940 butyl rubber (US)

1941 low density polyethylene

2

WW2

silicones,

fluorocarbons,

polyurethanes,

latex paints

1947 epoxy resins and adhesives

1948 acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene

polymer (ABS)

1949 polyester fiber

1950 acrylic fibers

1954 polyurethane foams in the US

1956 linear polyethylene

1957 polypropylene,

polycarbonates

1959 synthetic cis-polyisoprene

1960 ethylene propylene rubber

1960’s cyanoacrylate adhesives,

aromatic polyamides (Kevlar),

silane coupling agents

1980's

ultra high molecular weight

polyethylene fibers (Spectra)

3

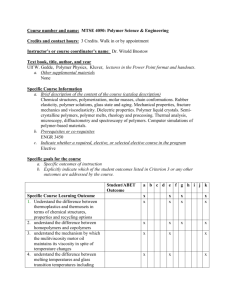

Manufacturer's Labeling Code:

The composition of an increasing number of plastic products is identified using the SPI (Society

for Plastics Industry) recycling code, which is usually stamped on the bottom of the product. The

number is often enclosed in the triangular arrows recycling symbol. The code is as follows.

Examples

1

PETE – Poly(ethylene terephthalate)

…………………………………

2

HDPE - High Density Polyethylene

…………………………………

3

V - Vinyl / Poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC)

…………………………………

4

LDPE - Low Density Polyethylene

…………………………………

5

PP – Polypropylene

…………………………………

6

PS – Polystyrene

…………………………………

Other

…………………………………

7

Poly(ethylene terephthalate), the pop bottle plastic is the most commonly recycled polymer.

You will need to learn the 7 SPI recycling symbols and names and abbreviations of the

corresponding plastics for your first and last test in this course.

4

Polymers are chain-like molecules of high molecular weight (also called ‘macromolecules’);

comprised of repeating structural units joined by covalent bonds. Polymers are built up from

smaller simpler molecules called ‘monomers’.

‘Poly’ means ‘many’ and ‘mer’ means ‘part’. A monomer is literally ‘one part’ of the many parts

in the polymer. A different monomer, or combination of monomers, is used to make each type or

family of polymer. For example, polyethylene is made by polymerizing ethylene ...

CH2=CH2 -CH2-CH2-CH2-CH2-

or

X (CH2-CH2)n -Y

where ‘X’ = an initial fragment

‘Y’ = a terminating fragment

-(CH2-CH2)n = repeating unit called a ‘mer’ or ‘mesomer’

‘n’ = number or mers in the polymer, called the ‘degree of polymerization’, “DP”

Note that for polymers formed from symmetric monomer units such as PE, (CH2-CH2)n, or

poly(tetrafluoroethylene), (CF2-CF2)n, (Teflon), the simplest repeat units would be -CH2- and

-CF2-, respectively but by convention both methylene groups (or difluoromethylene groups)

originating from the ethylene (CH2=CH2) or tetrafluoroethylene (CF2=CF2) monomer are shown.

The degree of polymerization varies from

molecule to molecule in a sample and varies from

sample to sample. That is to say that in a given

#

sample of polymer, e.g., polyethylene, not all

molecules

molecules are of the same length and same

molecular weight. The distribution of molecular

weights in a given sample generally follows a

Gaussian (Normal) distribution and the average or

most common molecular weight of the sample is

reported.

The average molecular weight of polymers varies

widely, e.g., 1000 to > 1,000,000 g/mol depending

upon how polymerization took place.

Molecular Weight

(g/mol)

Homopolymers are polymers made by polymerizing only one kind of monomer.

Copolymers are made by polymerizing > 1 type of monomer, i.e., comonomers, e.g., ethylene

and propylene comonomers can be polymerized together forming a polyethylene/polypropylene

copolymer ...

Terpolymers are copolymers comprised of 3 comonomers. Acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene

(ABS) is a terpolymer with high impact resistance used for residential DWV piping, and auto

body panels. It is not uncommon for coatings to be formulated with 3 or 4 comonomers. This is

done to modify the properties of a coating.

Ionomers are polymers with ionic groups such as carboxylate salts. Ionomers with many ionic

groups are used as polyelectrolytes for dispersing agents and flocculants.

Oligomers are short-chain polymers ('oligo' = few) with 50 DP 3.

High Polymers are very high or ultra high molecular weight polymers, i.e., MW > 106.

5

Arrangement or comonomers in copolymers:

1. Random:

2. Alternating

3. Block copolymers

4. Graft copolymers

Feedstocks for Polymers:

Ethylene, C2H4, the highest volume organic chemical in North America (and the fourth highest

industrial chemical) is also the largest volume monomer for plastics.

C2H4, 37 109 lb/yr in the USA, cost ca. 25 ¢/lb

Not only is it the monomer for polyethylene but it is the essential ingredient in vinyl

chloride (CH2=CHCl) and styrene (CH2=CH), the other two largest monomers for

plastics.

In N. America, ethane from natural gas is steam cracked at 700 C for ca. 1 s. ...

C2H6 C2H4 + H2 + other HC's

In Japan and Europe, the C5-C12 fraction (naphtha) of crude oil is cracked to produce

both C2H4 and gasoline.

Propylene and butadiene, two of the largest volume organics, are also produced as by

products

polyethylene

+ chlorine

+ benzene

ethylene

vinyl chloride

styrene

poly(vinyl chloride)

polystyrene

+ oxygen

ethylene oxide, ethylene glycol

polyethers

polyesters

polypropylene

+ ammonia

acrylonitrile

propylene

+ oxygen

+ benzene

propylene oxide

cumene, then phenol & acetone

acrylics

urethanes

phenolics

polybutadiene

butadiene

+ styrene

SBR rubber

+ chlorine

chloroprene

+ ammonia

hexamethylene diamine

neoprene

Nylon 66

6

Classification of Polymers Based on End Use:

1. Rubbers (also called Elastomers): In 1839, Goodyear discovered that mixing natural rubber

with sulfur gave a moldable composition that could be crosslinked (vulcanized) which

produced a useful, non tacky, stable material for waterproof raincoats, boots and tires. Even

today, about 70% of all rubber ends up in tires. The pneumatic tire (Dunlop, 1888) and the

use of carbon black as a reinforcing filler and organic accelerators for sulfur cross-linking

were achieved with natural rubber.

Since WW1, most natural rubber has been cultivated in Malaysia and Indonesia. Between

WW1 and WW2 a variety of synthetic rubbers have been developed especially in Germany

and the US, e.g., Thiokol and neoprene which have high chemical resistance, styrenebutadiene rubber (SBR) which is blended with natural rubber in tires, and nitrile, butyl, and

latex rubber.

Elastomers are polymers which be can stretched to at least twice their original length and

return to approximately their original length when stress is relieved.

Elastoplastics are polymers with properties intermediate between plastic and rubber, e.g. golf

ball covers.

2. Plastics (also called Resins): are synthetic (i.e., non-natural) polymers which are able to flow

(i.e., can be shaped, molded, or formed) at some stage. Celluloid and Bakelite were the first

plastics. Polyethylene (plastic bags), polystyrene (weigh boats) and poly(vinyl chloride)

(shower curtains) are among the largest volume plastics. Additives include fillers, colorants,

reinforcing agents, UV inhibitors, flame retardants, etc.

3. Fibers: are long strands of polymers (natural or synthetic) which are woven into fabrics, rope,

and cordage. Important fibers for the garment industry include wool, cotton, nylon,

polyesters. Polypropylene fibers are produced in large volumes for rope, furniture and carpet

manufacture.

4. Coatings : include paints, varnishes, and deposited films. Examples include latex, acrylic,

alkyd, oils, lacquers, epoxies, etc.

5. Adhesives and Sealants : are similar to coatings but differ in that they are used to bond two

different surfaces. Important examples of adhesives include cellulose acetate (paper glue),

epoxies, and cyanoacrylate (Crazy glue). Sealants include poly(dimethyl siloxane), silicone.

6. Films : are thin polymeric sheets such as those used in fabricating polyethylene bags and

vapor barriers, poly(vinylidene chloride) sheets (Saran wrap), etc.

7. Composites : combine resins and fillers as in fiberglass reinforced plastics (FRP), or polymer

films and polyaramid (Kevlar) or Spectra fibers (used in bullet proof vests). Light weight,

high strength materials are usually composites. Kevlar and Spectra polymers boast 10 times

the strength of steel on a weight basis. Other uses include aerospace products, e.g.,

helicopters.

8. Cellular Materials: include rigid and flexible foams, e.g., polyurethane foams in upholstery

and polystyrene foams in packaging materials and insulating materials.

9. Biopolymers: are naturally occurring macromolecules produced by plants and animals, e.g.,

fibrous proteins such as keratin (hair, horn, feathers, fingernails), globular proteins [casein

(milk), albumin (eggs), zein (corn)], polyamino acids, enzymes, etc.

7

Classification of Polymers Based on Structure:

Polymer chains are linear, branched or cross-linked ...

1. Linear:

2. Branched:

3. Crosslinked (or Network):

Functionality:

Carothers defined functionality as the number of bonds a monomer can form. All monomers

must be able to form at least 2 bonds per molecule, i.e., have a functionality of at least 2,

otherwise the molecules could not polymerize.

Ethylene, CH2=CH2, with 1 double bond can bond to 2 other molecules so it has a

functionality of 2. This is true for most vinyl compounds, i.e., vinyl chloride, styrene (vinyl

benzene), etc.

Butadiene, CH2=CH-CH=CH2, with 2 double bonds can bond to 4 other molecules so it has a

functionality of 4.

Ethylene glycol, HOCH2CH2OH, with 2 hydroxy groups, has a functionality of 2

What is the functionality of propanetriol, HOCH2CH(OH)CH2OH ?

Linear polymers (and some branched) are formed by monomers with a functionality of 2.

Network polymers (and some branched) require monomers with a functionality of at least 3.

Classification of Polymers as Thermoplastic or Thermoset:

Linear and branched chain polymers are thermoplastic, e.g., polyethylene, polystyrene, PVC.

Thermoplastics exhibit the following properties ...

1. they are linear or branched

2. soluble in appropriate solvents

3. fusible, i.e., melt when heated

4. waste materials can be recycled (10-20 ), but they gradually degrade after repeated cycling

Thermosets such as epoxies, rubber, phenolics, exhibit the following properties ...

1. they are crosslinked (or network) polymers

2. insoluble in solvents - don’t dissolve but may swell

3. infusible - cannot be melted (heat resistant) but will decompose at high enough temperature

4. once polymerized, they cannot be reprocessed (or only with difficulty, e.g., tires, foams)

8

Note that only thermoplastics can exhibit plastic flow and solubility because they are composed of large

but singular (unconnected) molecules. Thermosets are composed of an infinite network of bonded

molecules which cannot be separated without breaking covalent bonds. Rubber is a good example.

Natural rubber consists mostly of a linear polymer that can be crosslinked to a loose network by

reaction with 1 to 3% sulfur. The same polymer reacted with 40-50% sulfur is 'hard rubber', a

tight network polymer, used for pocket combs and bowling balls. We are accustomed to thinking

of molecules as submicroscopic; however the major portion of polymer in a tire or bowling ball is

really one molecule. This is because all the separate molecules in the tire were connected to one

another by sulfur cross-links during 'vulcanization'.

Calculate the molecular weight of a 10 pound bowling ball polymer. (ans. = 2.7 1027 g/mol)

Classification of Polymers by Chemical Makeup:

Polymer strengths are determined not only by the main chain covalent bond strengths (35-150

kcal/mol) but also by secondary intermolecular or van der Waals' forces (2-10 kcal/mol).

In general, covalent bond strength governs photochemical and thermal stability (decomposition).

For example, sulfur-vulcanized rubber is more likely to degrade at the comparatively weak -S-Sbonds (51 kcal/mol) than at the strong -C-C- bonds (83 kcal/mol).

On the other hand, secondary forces determine most of the physical properties we associate with

specific compounds. Melting, dissolving, vaporizing, adsorption, diffusion, deformation, and

flow involve the making and breaking of intermolecular 'bonds' so that molecules can move past

one another or away from each other.

Polymers with polar functional groups, particularly with H-bonding (-HO-, -HN-, -HF-,)

have strong intermolecular forces and have relatively high softening temperatures, e.g.,

PE (nonpolar HC) = ~110 C

Nylon 66 (polar, polyamide) = ~ 200 C

Cotton (cellulose) is a linear polymer but its high density of strong H-bonds gives it properties

normally associated with crosslinked polymers, i.e., insolubility and infusibility.

Kevlar (a crosslinked, polar, polyaramid) = ~500 C

Classification by Physical State:

Polymers may be partially crystalline or completely disordered (amorphous). The disordered

state may be glassy and brittle or it may be molten and viscous or it may be rubbery.

In general, branched and crosslinked polymers tend to be amorphous while a linear polymer can

be either amorphous or partly crystalline depending upon how it is manufactured. Branching

interferes with the orderly packing of molecules, so that crystallinity decreases.

If the polymer chain contains carbon atoms with two different substituents, the carbon is

asymmetric, since the two parts of the chain with which it is connected are different also. Such

asymmetric carbons can exist in two different spatial configurations which are not

interchangeable in stereoisomers without breaking covalent bonds. Vinyl polymers are formed in

any of three different configurations or 'tacticity'.

9

Consider the linear polymer, polypropylene.

CH3

CH3

CH2

CH

propylene

( CH2

C)

n

H

polypropylene

In the repeating unit, (the mer), every other carbon is asymmetric. Three tacticities of PP can

result. These are best visualized by looking at the polymer in its planar zigzag conformation.

isotactic PP has each pendant methyl group on the same side of the chain, that is all d or all l,

using the terminology of stereochemistry. The regularity of this arrangement allows orderly

packing necessary for high crystallinity. Isotactic polymers form helices to alleviate steric

strain.

syndiotactic PP has a regular alternation of pendant groups. This arrangement can also

produce high crystallinity and the planar zigzag conformation is sterically unhindered.

Random placement of methyl groups gives PP an atactic structure which cannot allow a

highly crystalline packing arrangement.

Until the advent of coordination complex catalysts, it was difficult to produce synthetically any

structure except atactic. Increasing the crystallinity of a polymer often improves its physical

properties, i.e., m.p., tensile strength, etc. So it is desirable to be able to control the

stereochemistry and hence the crystallinity during polymerization.

10

A second type of stereoisomerism in polymers is the cis-trans variety. Again, with the aid of

special catalysts, monomers like 1,3-butadiene can be polymerized to either the cis or trans

polymers (cis- or trans-1,4-polybutadiene in this example) ...

CH2=CH-CH=CH2

1,3-butadiene

( CH2-CH=CH-CH2 )

1,4-polybutadiene

Trans-1,4-polybutadiene, when vulcanized, produces a stiff inferior rubber.

Cis-1,4-polybutadiene produces a superior, flexible rubber

11

Nomenclature of Polymers:

As in the case of organic chemistry in general, the nomenclature of polymers is not fully

systematic and the actual nomenclature is a mixture of common and IUPAC names. The three

methods of naming polymers are ...

1. Common names based on the monomer: Add 'poly' as a prefix to the monomer name.

For example, ethylene polymerizes to polyethylene. For complex monomers, parentheses are

also added, e.g., vinyl chloride polymerizes to poly(vinyl chloride)

2. Trade names and acronyms: These are historical and industrial and must be memorized.

3. Nomenclature based on the IUPAC system: The simplest repeat unit in the polymer,

sometimes called the constitutional repeat unit, CRU, is named and then prefixed with 'poly'.

For example, (CH2-CH2)n is named polymethylene since the simplest repeat unit is actually CH2-. Similarly, (CF2-CF2)n is named poly(difluoromethylene).

Monomer

CF2=CF2

tetrafluoroethylene

Polymer

-(-CF2-CF2-)nTrade Name (Dupont)

Teflon

Common name

poly(tetrafluoroethylene)

IUPAC name

poly(difluoromethylene)

In order to write a common name for a polymer, one must know the name of the monomer.

12

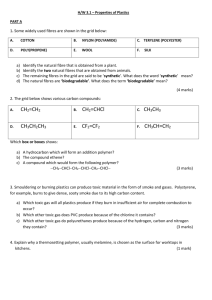

Name the following polymers. c = common, I = IUPAC.

)n

(

Cl

c:

I:

)n

(

O

O)

(

n

OH

c:

I:

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F

F F

F

F

F

F F

c:

I:

Cl

Cl

Cl

Cl

Cl

Cl

c:

I:

13

O

O

n

n

c

I

n

c

I

O

O

O

c

I

O

c

N

H

n

I

14

Complete the following tables and learn these important polymers:

Monomer Structure

CH2=CH2

CH2=CH(CH3)

Monomer Name

ethylene

propylene

Polymer Repeating Unit

CH2 CH2

n

Common Name (Abbrev.), Trade name

polyethylene (PE), (LDPE), (HDPE)

polypropylene, (PP)

Herculon upholstery,

vinyl chloride

poly(vinyl chloride), (PVC)

Vinyl, Tygon tubing

vinylidene chloride

poly(vinylidene chloride)

Saran wrap

tetrafluorethylene

poly(tetrafluoroethylene), (PTFE)

Teflon

styrene

polystyrene, (PS)

Styrofoam

vinyl acetate

poly(vinyl acetate), (PVA), (PVAc)

poly(vinyl alcohol), (PVAL)

15

Monomer Name

Common Name (Abbrev.), Trade name

acrylonitrile

polyacrylonitrile, (PAN)

Orlon fibre

acrylic acid

poly(acrylic acid)

methyl methacrylate

poly(methyl methacrylate), (PMMA)

Plexiglas, Lucite, Perspex

1,3-butadiene

trans-1,4-poly(1,3-butadiene)

1,3-butadiene

cis-1,4-poly(1,3-butadiene)

2-chloro-1,3-butadiene

polychloroprene,

(chloroprene)

Neoprene

2-methyl-1,3-butadiene

polyisoprene,

(isoprene)

cis-1,4-polyisosprene = latex rubber and

trans-1,4-polyisoprene = Gutta Percha

ethylene oxide

poly(ethylene oxide) = poly(oxy-ethylene)

Carbowax

formaldehyde

polyformaldehyde,

Delrin

16

Physical States and Transitions:

Consider a long, regular polymer chain connected by a series of single bonds, e.g. PE or

polystyrene (PS). With the potential for free rotation around single bond, the chain might assume

an infinite number of conformations in space, however, during these rotations, the bond angles and

distances remain fixed. Three extreme conditions of physical state are possible ...

1. Completely free rotation. When a polymer, i.e., a thermoplastic is heated above its melting

temperature, its continuously wriggling molecules can slip past each other. The higher the

temperature, the more intense the molecular motion. This state is a 'melt'.

2. No rotation. On cooling a polymer from the melt, at some sufficiently low temperature, the

polymer will not have sufficient kinetic energy to overcome the energy barriers (steric

hindrance or polar attraction) for rotation around single bonds to occur. If the cooling was

rapid, molecules do not have time to arrange themselves in an ordered (crystalline) manner

and are trapped in a disordered, chaotic, entangled state called a 'glass'. It is amorphous.

3. Packing. If cooled slowly from the melt (or stretched while cooling) the chains of polymer

may align themselves into a regular crystallatice. This is the 'crystalline' state.

Each of these is a simplification. Other factors modify the physical state of a polymer, e.g.,

the presence of double bonds in the chain do not permit free rotation

thermoset (crosslinked) polymers inhibit rotation

longer chains experience greater intermolecular attraction and entanglement per

molecule than shorter chains of the same polymer, i.e., MW is a variable

branching interferes with orderly packing

the presence of large bulky groups inhibit rotation, e.g., PS is largely amorphous

the presence of highly polar groups resist free rotation

the presence of solvents allow rotation below the normal solidification temperature

As a result, polymers may be completely amorphous, partly crystalline, or wholly crystalline.

Amorphous polymers tend to be transparent, e.g., amorphous poly(ethylene terephthalate), (PET),

for pop bottles and poly(vinylidene chloride) for Saran Wrap. Crystalline polymers are opaque;

their crystals scatter light, e.g. 95% crystalline High Density Polyethylene (HDPE). Partly

crystalline polymers contain crystalline domains (crystallites) mixed with amorphous domains,

e.g., 55% crystalline Low Density Polyethylene, (LDPE), for plastic bags is translucent.

Two main polymer transition temperatures are the melting temperature, Tm, and the stiffening

temperature, properly called the glass transition temperature, Tg.

Tm, sometimes called ‘the first-order’ transition temperature is often actually a temp. range.

Tg, sometimes called ‘the second-order’ transition temperature defines a boundary between the

rubbery or plastic state and the brittle, glass state. Many polymers show an abrupt change in

physical properties at this point, i.e., density, specific heat, and refractive index as well as

flexibility, elasticity, and dielectric properties.

17

The following figure shows the changes in specific volume with temperature for an amorphous

polymer not having a true melting point, as well as for a crystalline polymer.

Tg is assumed to be the same for both polymers.

Note the abrupt change in density at Tg as

segmental motion stops.

amorphous

By rapidly cooling a crystalline polymer specific

volume

from the melt, it may follow the upper (mL/g)

crystalline

(amorphous) curve since rapid solidification

may not allow time needed for orderly

packing but may freeze the molecules in the

tangled, melt-like arrangement.

Plasticizers are nonvolatile solvents purposely

added to lower the stiffness (Tg) of a polymer.

The plasticizer occupies space between

molecular chains and reduces intermolecular

Tg

attraction acting as a lubricant. For example,

Tm

polyvinyl chloride, a stiff polymer with a high

Tg (82ºC) is made flexible by the addition of up to 40% dioctylphthalate or tricresylphosphate

plasticizer. Tg drops to ca. -80 C. The result is a flexible plastic used for raincoats and shower

curtains. Fogging or ‘sweating’ may occur at high temperatures, i.e., migration of the plasticizer

occurs eventually resulting in the onset of embrittlement.

Many commercial fibers are plasticized by small amounts of water. The familiar process of steam

ironing a garment usually takes place between Tg and Tm. The moisture lowers Tg below the iron

temperature allowing the removal of creases (due to polymer flow). The garment’s shape is locked in place

when the heat and moisture are removed leaving a wrinkle free appearance.

Values of Tg for some common plastics are listed. Study these and be able to explain the relative

differences using the previously listed factors.

Polymer

Tm (C)

Tg (C)

polyethylene (high density-high MW)

137

-120

polyethylene (low density-low MW)

100

polybutadiene (random)

polybutadiene (cis)

-85

ca. 10

-102

poly(ethylene terephthalate)

267

69

poly(vinyl chloride)

212

82

polystyrene (isotactic)

240

100

poly(methyl methacrylate)

105

polypropylene (atactic)

ca. 130

-20

polypropylene (isotactic)

ca. 160

30

Completely amorphous polymers have a Tg but no Tm. Completely crystalline polymers have a

Tm but no Tg. Partially crystalline polymers have both a Tg and a Tm.

18

Structure and Properties Conventional Polyethylenes:

As a result of different polymerization processes for commercial PE and the versatility of

these processes, a number of types of PE are manufactured, each specially engineered for

particular applications. Table II compares some of the fundamental properties of the more

important commercial PE's. Amorphous PE and highly crystalline polymethylene are also

included to delineate the full range of properties attainable with PE.

Table II. Physical properties of polyethylenes related to molecular structure.

Type

Crystallinity

of

%

Density

g/cm3

PE

Melting

Point

Tensile

# Branches

Strength

per 1,000

C

MPa

C atoms

Amorphous

0

0.85

-

-

-

LDPE

50-70

0.91-0.925

106-112

9-15

20-40

LLDPE

65-80

0.92-0.94

125

13-20

10-25

HDPE

80-95

0.941-0.965

125-138

21-37

< 5-10

Polymethylene

> 95

0.97

143

-

unbranched

The tabled data reveals clear trends which can be understood in terms of the molecular structure of

these polymers. The structural variables are twofold: (1)...the length and frequency of occurrence

of chain branching, (2)...the average molecular weight and molecular weight distribution. In the

case of polyethylenes, the stereochemistry of the polymer is not a variable because of the

symmetry of the ethylene monomer.

Crystallinity:

The extent to which polymer molecules will crystallize depends on their structures and on

the magnitudes of the secondary bond forces (van der Waals' forces) among the polymer chains.

The greater the linearity of the polymer molecule and the stronger the secondary forces, the

greater the tendency toward crystallization.

Linear PE has essentially the best structure for chain packing. Its molecular structure is very

simple and perfectly regular, and the small methylene groups fit easily into a crystal lattice.

Linear high density PE, with infrequent branching, therefore crystallizes easily and to a high

degree (over 90%) even though its secondary forces are small.

Branching impairs the regularity of the structure and makes chain packing difficult. Branched

low density PE, with frequent branching, is thus only partially (50-70%) crystalline. Many of

the differences in physical properties between low-density and high-density PE's can be

attributed to the higher crystallinity of the latter.

Thus, linear PE has higher density than the branched material (density range of 0.94-0.965

g/cm3 vs 0.91-0.94 g/cm3), higher melting point (typically >125 C vs. 112 C), greater

stiffness and tensile strength, greater hardness, and less permeability to gases and vapors.

19

Molecular Weight:

Because of their large molecular size, polymers possess unique chemical and physical properties.

These properties begin to appear when the polymer chain is of sufficient length, i.e., when the

molecular weight exceeds a threshold value, and becomes more prominent as the size of the

molecule increases.

Note the increase in melting points with increasing molecular weight in the paraffin series:

C20H42 (35 C), C30H62 (65 C), C40H82 (81 C), C50H102 (92 C), C60H122 (99 C), and

C70H142 (105 C). Highly linear polyethylene of molecular weight greater than three million

exhibits a melting point of 132 C. The melting point of 100% crystalline, completely

unbranched polyethylenes of infinitely high molecular weight (density at 25 C of 1.002

g/cm3) is reported as 143 C.

The dependence of the melting point of polyethylene on the degree of polymerization (DP) is

shown

in

Figure

2.

140

120

100

80

mp

60

(° C)

40

20

0

0

500

1000

1500

DP of PE

Figure 2. Melting point of PE versus degree of polymerization.

The dimer of ethylene is a gas, but oligomers with a DP of 3 or more (that is, C6 or higher

paraffins) are liquids, with the liquid viscosity increasing with the chain length. Polyethylenes

with DP of about 30 are grease-like, and those with DP around 50 are waxes.

As the DP value exceeds 400, or the molecular weight exceeds about 10,000, polyethylenes

become hard resins with melting points above 100 °C. The increase in melting point with

chain length in the higher molecular weight range is small. Here crystallinity has a greater

influence on the melting point.

20

Figure 3: Variation of Physical Properties with Molecular Weight

com m ercial range

of P E' s

P

r

o

p

e

r

t

y

tensile strength

im pact strength

m elt viscosity

Molecular Weight

Variation in molecular weight will also lead to differences in mechanical properties, i.e., the

higher the molecular weight the greater the number of points of attraction and entanglement

between molecules. Increased molecular entanglement hinders crystalline packing and thereby

lowers density.

Molecular weight also influences properties related to large solid deformations, i.e., tensile

strength, impact strength, elongation at break, and melt viscosity; all of these increasing with

higher molecular weight. Note in Figure 3 that the strength properties increase rapidly at first

as the chain length increases and then level off, but the melt viscosity continues to increase

rapidly.

Polymers with very high molecular weights have superior mechanical properties but are

difficult to process and fabricate due to their high melt viscosities. The range of molecular

weights chosen for commercial polymers represents a compromise between maximum

properties and processability.

21

Molecular Weight Distribution of Polymers:

In ordinary chemical compounds such as sucrose, all molecules are the same size and

therefore have identical molecular weights (M). Such compounds are said to be monodisperse. In

contrast, virtually all synthetic polymers and some natural polymers are polydisperse. Thus most

polymers do not contain molecules of the same size and therefore do not have a single molecular

weight.

The extent of variation of molecular weight and size in a polymer sample is known as its

molecular weight distribution, (MWD) and the MWD has considerable influence upon the

physical properties of the polymer.

The molecular weight of a polymer is reported as an average. Since it is not generally possible to

physically segregate, count and weigh all the molecules of a sample, average molecular weight is

determined by a variety of techniques, each giving slightly differing values.

Methods of determining molecular weight include the following

1. end group analysis, e.g., titration of reactive end groups such as carboxylic acid groups

or amine groups

2. colligative properties, i.e., vapor pressure lowering, boiling point elevation, freezing

point depression, and osmotic pressure. Recall that each of these effects are

proportional to the number of moles of solute (polymer) present in a solvent.

3. light scattering: The intensity of light scattered is proportional to the square of the

mass of the particle in solution

4. ultracentrifuge: After centrifuging a solution of the polymer at high speeds for several

weeks, a concentration gradient is established with larger particles in the lower layers

of the solution. The concentration of polymer at various depths is then determined by

optical methods.

5. viscosity: Ostwalt viscometers are used to measure relative viscosity of dilute solutions of

polymers. The viscosity is directly proportional to the polymer chain length.

6. gel permeation chromatography: (size exclusion chromatography). A crosslinked

porous polystyrene packing ('gel') separates polymer molecules based on their size.

The flow of smaller polymer molecules is slowed down as they diffuse into the pores of

the gel while larger molecules move through the column more quickly. A suitable

detector (e.g. photometer, conductance, etc.) indicates the relative concentrations.

22

Molecular Weight Determination of Polymers

A non polymeric substance has a fixed molecular weight. For example, all glucose molecules

(C6H12O6) have the same molecular weight (180.15 g/mol).

A sample of a polymer contains chains of different lengths. Thus a polymer does not have an

exact and absolute molecular weight. If we could separate all polymer chains in a sample and

count the number of chains of each weight, we could then calculate an average molecular weight

for a given sample. This is physically impossible to do.

In order to determine the average MW of a polymer sample we conduct chemical and/or physical

tests. Different tests may give different values for the molecular weight of the same sample. The

tests may be grouped into three types; number average MW tests, weight average MW tests and

viscosity average MW tests.

Number Average MW Tests:

These tests measure the number of molecules present in a sample.

1. End Group Analysis involves titrating reactive end groups with a standard acid or base

titrant. This only works for polymers that have reactive end groups. For example,

polyesters (made by reacting a diol with excess diacid) will have carboxylic acid end

groups on all chains. Titration of a weighed portion of the polymer with standard NaOH

yields the number average MW of the polymer. Similarly, a polyamide made by reacting

a diacyl chloride with excess diamine produces a polymer with amine end groups on all

chains. They can be titrated with standard HCl titrant.

Calculate the number average MW of a polyester given that titration of a 10.00 g sample

requires 50.00 mL of 0.0100 M NaOH titrant. (ans. 40,000 g/mol)

23

2. Colligative Properties include vapor pressure lowering, boiling point elevation, freezing

point depression and osmotic pressure. These properties vary in proportion to the number

of moles (mole fraction) of a substance and hold for both polymeric and non polymeric

substances.

a) Vapor Pressure Lowering: Recall from Raoult’s law that the vapor pressure above a

solution is inversely proportional to the mole fraction of non volatile solute dissolved in a

solution.

Psoln = (P0solvent)(xsolvent)

where P = vapor pressure and x = mole fraction

A solution of the polymer can be boiled at room temperature by evacuating the vapor

space above the solution. Since a liquid boils when its vapor pressure equals the pressure

of atmosphere above it, the polymer solution will boil when the applied pressure becomes

equal to the vapor pressure of the solution. By accurately measuring this pressure and the

pressure at which pure solvent boils (at the same temperature), the number average MW

can be calculated.

Calculate the number average MW of a water soluble polymer given the following data.

10.000g polymer are dissolved in 36.03 g H2O. At 20°C this solution boils at 17.46

mmHg. At the same temperature, pure H2O boils at 17.53 mmHg. (ans. = 1247 g/mol)

b) Boiling Point Elevation: The boiling point of a liquid is elevated if a non volatile solute is

dissolved in it (because its vapor pressure is lowered as explained above).

Tb = kbm where Tb = bpelevation, m = molality of solute, kb is constant for a solvent

Calculate the number average MW of a polymer given that when 10.000g polymer are

dissolved in 100.00 g CCl4, the solution boils at 76.84 °C. The normal bp of CCl4 is

76.74 °C. The molal bp elevation constant for CCl4 is 4.95 Kelvinskgsolventmolesolute-1.

(ans. = 4950 g/mol)

24

c) Freezing Point Depression: The freezing point of a liquid is depressed when a non volatile

solute is dissolved in it. (Recall that NaCl and/or CaCl2 are applied to roads to melt ice,

by lowering the freezing point of water).

Tf = kfm where Tf = fpdepression, m = molality of solute, kf is constant for a solvent

Calculate the number average MW of water soluble polymer given that the freezing point

of an aqueous solution of the polymer is –0.14 °C. The solution is prepared by dissolving

72.00 g polymer in 500.00 g H2O. The molal fp depression constant for water is 1.86

Kelvinskgsolventmolesolute-1. (ans. = 1910 g/mol)

d) Osmotic Pressure: Osmotic pressure is that pressure, which must be applied to a solution

to prevent osmosis, i.e., to prevent the passage of pure solvent through a semi permeable

membrane into a solution.

= MRT where = osmotic pressure. M = molarity, R = gas constant, T = Kelvins.

Unlike the other colligative properties, osmotic pressure displays a large response for

even dilute solutions. For example, calculate the osmotic pressure (atm and m H2O) of a

solution of 6.00 g urea (MW = 60.0 g/mol) dissolved in 2.00 L H2O at 20°C. The gas

constant (R) is 0.08206 Latmmol-1K-1. (ans. = 1.20 atm and 12.4 m H2O!)

Calculate the number average MW of a water soluble polymer given that when 15.00 g

polymer is dissolved and diluted to 200.00 mL, its osmotic pressure at 20°C measures

0.00605 atm (ans. = 298,000 g/mol)

25

Weight Average Molecular Weight Tests:

1. Light Scattering: Solutions of non polymeric

solutes, like aqueous NaCl, are transparent to light

because the solute and solvent molecules are much

smaller than the wavelength of light. The light

bends around small molecules and ions and such

particles are therefore invisible. Polymer molecules,

however, are larger than the wavelength of UV and,

in some cases, visible light.

Intensity

These tests measure the average size of polymer molecules. Size is proportional to weight.

weight avg. MW

When light passes through a solution of polymeric

solutes, the light is scattered. The intensity of light

scattered is proportional to the square of the mass of

the particle in solution.

To use light scattering to measure MW, one needs a series of standards of equal

concentration but varying and known MW. A calibration curve of intensity of scattered light

vs. weight average MW is plotted. The intensity of light scattered by a solution of the same

type of polymer at equal concentration is measured and its weight average MW is read

from a graph.

2. Ultracentrifuge: After centrifuging a solution of the polymer at high speeds for several

weeks, a concentration gradient is established with larger particles in the lower layers of

the solution. The concentration of polymer at various depths is then determined by

optical methods.

3. Gel Permeation Chromatography: (size exclusion chromatography). A crosslinked

porous, polystyrene packing ('gel') separates polymer molecules based on their size. The

flow of smaller polymer molecules is slowed down as they diffuse into the pores of the

gel while larger molecules move through the column more quickly. A suitable detector

(e.g. photometer, conductance, etc.) indicates the relative concentrations.

Ostwalt viscometers are used to measure relative viscosity

of dilute solutions of polymers. The viscosity is directly

proportional to the polymer chain length. To determine the

viscosity average MW of a polymer, one must first prepare

a series of standards of equal concentration but varying and

known MW. The viscosity of a solution of the same type of

polymer at equal concentration is measured and its

viscosity average MW is read from a graph.

Viscosity

Viscosity Average Molecular Weight:

viscosity avg.

MW

26

Number-Average Molecular Weight:

The number-average molecular weight, Mn, is the common arithmetic mean calculated by counting

the number of molecules (or moles) of each particular size, summing these, and then dividing this

sum by the total number of molecules (or moles), just as the average score in a series of organic

tests is calculated by adding all scores and dividing by the number of tests.

Mn

N 1M1 N 2 M 2

N1 N 2

N M

N

i

i

i

Ni = # moles polymer with molecular wt. = Mi

n i M i n = mole fraction polymer with molec. wt. = M

i

i

Weight-Average Molecular Weight:

In the calculation of Mn, the molecular weight of each species was multiplied by the mole fraction

of that species. Similarly, in the calculation of weight-average molecular weight, Mw, the

molecular weight of each species is multiplied by the weight fraction of that species.

2

Wi = wt. of polymer with molecular wt. = Mi

Wi M i N i M i

Mw w i M i

Wi N i M i wi = weight fraction of polymer with molec. wt. = Mi

Example: A polyethylene sample contains 50 mol %

of a species with molecular weight of 10,000 g/mol and 50 mol % of species of molecular weight

20,000 g/mol.

Calculate Mn, Mw, DPn, and DPw. Note that

DP = ( M/weight of a mer)

Ans: Mn = 15,000, Mw = 17,000, DPn = 540, DPw = 610

27

Both Mn and Mw are theoretical concepts and are not calculated in the manner of the previous

example. The example serves to illustrate the concepts. The reason for introducing different

measures of average molecular weight is because the various analytic techniques described above

give different values for average molecular weight.

Mn is obtained by end-group analysis and by colligative properties. These methods measure

the number of molecules in a sample.

Mw is obtained by light scattering techniques (photometric methods). Light scattering is

dependent upon the size (weight) of particles.

Polydispersity Index:

For all polydisperse polymers Mw is always greater than Mn. Only in the case of a monodisperse,

where all molecules are the same size, does Mw = Mn.

The ratio Mw/Mn, called the polydispersity index, is a measure of the MWD of a polymer.

The farther the polydisperse is from 1.0, the wider the MWD of a sample. Some typical data is

given in the following table ...

Polymer

Mn ( 10-3)

Mw ( 10-3)

Mw/Mn

alkyd resins

25 - 50

50 - 200

2-4

epoxy resins

0.35 - 4

0.35 - 7

1.0 - 2.5

acrylic polymer

25 - 350

40 - 600

1.1 - 1.8

polybutadiene

2 - 50

2.1 - 52

1.05 - 1.1

A large polydispersity index indicates a polymer is more deformable (reduced stiffness,

increased toughness) and of lower melt viscosity than a sample of the same polymer with a

lower index; the presence of short chains acts as a plasticizer by reducing entanglement of the

larger polymer chains.

Viscosity-Average Molecular Weight:

Because viscosity measurement of a polymer solution is comparatively simple, this method is

commonly performed and the molecular weight determined by this method is called viscosityaverage molecular weight, Mv. Values of Mv always lie between Mw and Mn and are usually 10

to 20% below Mw.

28

Methods of Polymerization:

Two basic methods of polymerization are catalytic or non-catalytic and both of these are

subdivided ...

I.

II.

Non-catalytic methods:

A.

Thermal methods use heat to cause polymerization, e.g., polystyrene and

poly(tetrafluoroethylene) (PTFE, trade name Teflon).

B.

U.V. light causes photochemical polymerization

C.

Electrolytic polymerization occurs at the anode or cathode of an electrochemical

cell as a result of electric current.

D.

Gamma radiation from Co60 has been used to avoid contamination from other

ingredients.

Catalytic methods:

A.

Free radicals act as catalysts (loosely) in chain polymerization mechanisms

B.

Ions (cations or anions) act as catalysts in polymerizations

C.

Co-ordination catalysts are stereo specific. Most famous are the Ziegler-Natta

supported metal salts which allow the formation of high density, high crystallinity

PE, PP, etc.

Types of Polymerization:

1. Chain reaction polymerization or ‘addition’ polymerization may occur via any of a free radical

mechanism, a cationic or anionic mechanism, or a co-ordination catalyst mechanism. The

common examples are vinyl polymerizations, i.e., polyethylene and polybutadiene in which

double bonds are opened.

2. Stepwise or Step-Growth polymerization often occurs with the elimination of a small

molecule, e.g., water. For example, ethylene glycol condenses with terephthalic acid to

eliminate water and produce polyethylene terephthalate, (PET) by esterification. Similarly,

diamines react with dicarboxylic acids in an acid-base reaction eliminating water and forming

polyamides (nylon). Polyurethanes area also produced by stepwise growth, but with

rearrangement rather than elimination of a small molecule.

3. Ring opening also called ‘ring scission’ occurs with cyclic monomers having functional groups

on the same molecule, which can react together in a sequence of ring-opening and

polyaddition. Poly(ethylene oxide) and nylon 6 are representative of this polymerization type.

29

Free Radical Chain-Growth Polymerizations:

Free radical polymerization proceeds by the following three-part process ...

a) initiation, b) propagation, c) termination and chain transfer

A) Initiation: is the formation of an active species, which is then capable of starting the

polymerization of the otherwise unreactive monomer. It may be brought about by heat or light

(e.g., UV) but is most commonly achieved by addition of an initiator; a material which, on

heating or other stimulation decomposes into free radicals. A free radical is an organic

molecule containing atoms with unpaired electrons.

The free radical initiators are usually either peroxides or azo compounds with weak

covalent bonds capable of undergoing homolytic cleavage. Acyl peroxides such as

benzoyl peroxide typically decompose upon heating in a two-step process. In the first

step, homolytic cleavage of the weak O-O peroxide bond yields two acyloxy radicals.

These acyloxy radicals then decompose to form two aryl (or alky) radicals and CO2 ....

Another common class of initiators used in radical polymerizations are azo compounds

such as azobisisobutyronitrile, (AIBN), which decompose on heating or by the

absorption of UV light to produce two organic radicals and N2 ....

The foregoing reactions can be summarized as ... I - I 2 I where I = initiator.

The second part of initiation is the addition of the initiator radical to the monomer to give an

initiated monomer radical ...

B) Propagation: The newly initiated monomer radical adds further monomer molecules in rapid

succession (propagates) to form a polymer chain. The active center is continually relocated to

the end of the chain.

30

Radical additions to double bonds occur in such a way as to always give the more stable (more

substituted) radical.

As a result, free-radical polymerized vinyl polymers contain

98% 'head-to-tail linkages'.

C) Propagation continues until the growing, long-chain radical becomes deactivated by

termination or chain transfer.

Termination: Polymerization stops when the growing, long-chain radical becomes completely

deactivated by either combination (also called coupling) or by disproportionation.

Combination (or coupling) occurs when 2 long chain radicals react to form an inert final

polymer. Combination is a rapid, diffusion-controlled process that occurs without an

activation barrier. In order to suppress this unwanted reaction, the concentration of initiator is

kept low (~ 10-9 to 10-7 M). [Relatively few chains are activated].

Disproportionation involves the abstraction of an H atom in the beta position to the

propagating radical of one chain by the radical end group of another chain. This process

results in two dead chains, one terminated in an alkane and the other in an alkene.

Chain Transfer: occurs when H is abstracted by the radical end group from the side of another

polymer chain, a solvent molecule, or another monomer. These terminate one chain but at the

same time, begin another chain. Thus there is no net change in the radical concentration. The

results of chain transfer are formation of side chains in polymer molecules.

AB may be monomer, polymer, solvent, or added modifier (chain transfer agent). Mercaptans

such as dodecyl mercaptan, (C12H25SH), and chlorinated solvents, such as CCl4, are common

chain transfer agents. Depending upon its reactivity, the new radical, B, may or may not

initiate the growth of another polymer. Chain transfer agents are sometimes added to lower

molecular weight.

31

Redox Initiation:

In aqueous medium free radical polymerization, the dissociation of peroxide or persulfate

initiators is greatly accelerated by the presence of a reducing agent such as HSO3- or Fe+2

e.g., K2S2O8 initiator plus NaHSO3 reducing agent

S2O8-2 + HSO3- SO4-2 + SO4- + HSO3

e.g., hydroperoxide initiator plus FeSO47H2O complexed in EDTA

ROOH + Fe+2 RO + OH- + Fe+3

The use of redox initiators allows attainment of high rates of free radical formation at low

temperatures, even below 0 C.

Inhibitors for Free Radical Polymerization:

Oxygen reacts with free radicals forming peroxides or hydroperoxides stopping polymerization

and causing chain transfer. The result is short oligomeric chains. Thus many free radical

polymerizations are carried out in oxygen-free conditions, e.g., nitrogen atmosphere.

In some cases, as with styrene, a small amount of inhibitor such as hydroquinone or butylated

hydroxytoluene (BHT) is added to prevent premature polymerization. These inhibitors stabilize

free radicals by resonance and thus suppress polymerization. When polymerization is to be carried

out extra initiator must be added.

Autoacceleration:

Chain polymerizations of vinyl monomers are very exothermic. As polymerization proceeds,

viscosity increases.

The propagation rate is relatively constant as monomers move freely to the reactive chain ends of

the growing polymer. However, termination rate slows down as the growing chains become less

mobile. As a result, the rate of polymerization increases (autoaccelerates) along with the growing

exotherm.

This behavior, called a 'Tromsdorff-Norish Effect', can cause violent explosions, unless the

temperature is controlled by cooling, especially in 'mass' ('bulk') polymerizations where solvent is

not used. High molecular weight results for the same reasons.

32

Free Radical Polymerization of Dienes:

Conjugated dienes, like vinyl monomers, undergo polymerization through their multiple bonds.

Free radical, as well as ionic and coordination process (described later) are used. Industrially

important dienes are butadiene, chloroprene, and isoprene ...

Dienes can give rise to polymers, which contain various isomeric structural units. Each of the

above structures contains a 1,2- and a 3,4- double bond, therefore, there is the possibility that

either double bond may participate independently in polymerization - giving rise to 1,2- units and

3,4- units, respectively ...

With symmetrical dienes such as butadiene, these two units become identical. A further

possibility is that both bonds are involved in polymerization through conjugate reactions,

producing 1,4- units. A 1,4- unit may occur as either the cis- or trans- isomer ...

In general, the polymer obtained from a conjugated diene contains more than one of the above

structural units. The relative frequency of each type depends upon the nature of the initiator,

experimental conditions, and the structure of the diene.

Ionic Chain-Growth Polymerizations:

Ionic polymerizations are those in which the chain carriers are organic ions.

Anionic polymerizations involve carbanions (C-).

Cationic polymerizations involve carbocations, also called 'carbonium' ions or 'carbenium' ions,

(C+).

The choice of ionic procedure depends greatly upon the electronic nature of the monomer to be

polymerized. Vinyl monomers with electron withdrawing groups, which stabilize carbanions, are

used in anionic polymerizations, whereas vinyl monomers with electron donating groups are used

for cationic polymerizations.

33

Recognizing Electron Donating and Electron Withdrawing Groups

Recall: Substituents on aromatic rings affect both reactivity and orientation (location) of

electrophilic aromatic substitution (EAS). For example, note the relative rates of nitration of the

following aromatic compounds ....

-OH

1000

-H

1

-Cl

0.033

-NO2

6 10-8

Substituents affect EAS when they either donate or withdraw electron density to or from the ring.

Substituents which donate electron density make the ring a better Nu:- and stabilize the C+

intermediate and thus activate the ring toward EAS

Substituents which withdraw electron density make the ring a poorer Nu:- and destabilize the

C+ and thus deactivate the ring toward EAS

Substituents donate or withdraw electron density by either or both of the following two

mechanisms, i.e., inductive effect or resonance effect

Inductive Effect refers to movement of electron density through bonds due to EN between the

aromatic C and the atom bonded to it, e.g., halogens, carbonyl, cyano & nitro groups withdraw edensity from the ring. Alkyl groups donate e- density because they are relatively large &

polarizable. Also the sp2 C in the ring is more electronegative (1/3 s-character) than the sp3 alkyl

group carbon (1/4 s-character). S-orbitals are closer to the nucleus and hold their electrons tighter.

O

C

Cl

O

+

N

C N

CH3

O

Resonance Effect refers to movement of electron density through bonds via overlapping porbitals especially in conjugated systems. Atoms that have non bonded, lone-pair electrons and

that are bonded directly to an aromatic or allylic system are able to transfer electron density in this

manner. For example, the sp3 oxygen in phenol hybridizes to sp2, moving lone-pair e- density into

the ring through the system via overlap of the oxygen 2p orbital with the ring carbon’s 2p

orbital.

3px

2p

C

C

C

.

C

C

2p

:

C

O

.

H

3py

sp2

C

C

C

C

C

C

3pz

Cl

3pz

3s

34

Note that the same atom can withdraw electron density inductively and donate electron density by

resonance at the same time. The net effect depends upon which one is greater. For example, the OH is electron donating by resonance but electron withdrawing inductively, however, the

-OH group is ring activating so its resonance effect must be greater than its inductive effect.

Electron withdrawing groups have the general form, -Y=Z, where Z is more EN than Y

Electron donating groups have the general form, -Y: , where Y has 1 lone-pair of electrons

Aromatic substituents are of 3 types ...

1. ring activating and o-, p- directing, e.g., , -NH2, -NHR, -NR2, -OH, -OR, and -R groups

2. ring deactivating and o-, p- directing, e.g., -X groups (the halogens)

3. ring deactivating and m- directing, e.g., -NO2, -SO3H, COOH, CN, -NR3+ groups

o- and pdirecting

NH2

OCH3

o- and pdirecting

F

CH3

m-directing

Br

O

O

CH

C OH

O

NH C CH3

H

Cl

I

deactivators

activators

Electron Donor

Groups

NO2

Reactivity

Reactivity

OH

SO3H

O

O

COCH3

C CH3

C N

N+R3

deactivators

Weak electron

withdrawing groups

Strong electron

withdrawing groups

Increasing ability to donate electrons to sp2 hybridized carbon atoms.

35

Indicate which of the following monomers would be suitable for anionic or cationic

polymerization ...

CN

CO2R

CN

CO2R

CO2R

OR

Draw resonance structures to show how styrene can stabilize either a benzylic cation or anion

through resonance.

Both water and oxygen can react with and deactivate ionic end groups and so both must be

carefully excluded from these reactions.

Both anionic and cationic polymerizations are run at very low temperatures (e.g., -78 C) to

reduce the frequency of unwanted terminations and transfer reactions.

36

Anionic Polymerizations:

Anionic polymerizations can be initiated by

a) addition of a Nu:- to the alkene monomer or

b) an electron-transfer process

The nucleophilic addition uses metal alkyls such as methyl- or sec-butyllithium. The newly

formed carbanion then acts as a nucleophile and adds to another monomer and the propagation

continues ...

In the electron transfer process, an active metal such as Li or Na donates 1 electron to the

monomer converting it to a radical anion. The radical anion then can either be further reduced

to a dianion or can dimerize, again yielding a dianion ...

In either case, a single initiator can now propagate chains from both ends because it has two

active end group carbanions.

Initiation is heterogeneous using a metal reducing agent. Alternately, a homogeneous

initiation is performed by first reducing naphthalene with Na to produce sodium naphthalide

radical anion, which is soluble. Sodium naphthalide reacts with alkene monomers such as

styrene producing a radical anion monomer, which couples to form the dianion as previously

described. The dianion then propagates at both ends, growing chains in both directions.

37

The propagation of anionic polymerizations is similar to free radical polymerizations with the

important distinction that many of the chain-transfer and termination reactions that plague

radical processes are absent, i.e., since propagating chain ends carry the same, negative charge,

bimolecular coupling and disproportionation reactions are unlikely. In absence of chain

transfer reactions, ionic polymerizations produce polymers with narrow molecular weight

distributions, i.e., with polydispersity indices of 1.1 or less, under ideal conditions. Compare

this with chain-growth polymers that typically have polydispersity indices of 2 or higher.

Note that since carbanions are strong bases that will abstract protons, anionic polymerizations

require solvents and monomers that do not have acidic protons otherwise termination may

occur.

With careful attention to these conditions and clean reagents and equipment, propagation will

continue until all monomer is consumed yet the polymer ends remain active. This is called

'living polymerization', i.e., the polymer chains remain alive (active). Molecular weight can

now be controlled. More monomer can be added to increase the molecular weight or the

polymer chains can be terminated (killed) at this point by adding a monomer with an acidic

proton, e.g., alcohol or water.

Another way to terminate the chains is to add electrophilic terminating agents that will

functionalize the end groups. For example, CO2 or ethylene oxide will terminate the chains

and produce carboxylic acid and alcohol groups, respectively.

If a different monomer is added, block copolymers are produced. For example, stiff, brittle

polystyrene (Tg = 100 C) and rubbery poly(1,4-cis-butadiene) (Tg = -102 C), when formed

as a 'tri-block' copolymer (styrene-1,4-cis-polybutadiene-styrene), behaves like a cross-linked

elastomer. Unlike true network elastomers, this tri-block can be melted and reprocessed.

38

Problem: Write a complete mechanism for the polymerization of PS initiated with naphthalene

and sodium and terminated with water. Label the steps as initiation, propagation, and termination.

Cationic Polymerization:

Like anionic polymerizations, cationic polymerizations are carried out at low temperatures and

with pure, clean reagents and equipment. Only alkenes with electron donating groups (alkyl, aryl,

ether, amino groups, etc.) are polymerized cationically.

Initiation is with a strong protic acid or with a Lewis acid. The protic acid must have a nonnucleophilic counterion in order to avoid 1,2-addition across the double bond. Suitable

counter ions include SO4-2, AsF6-, and BF4- ...

Alternately, a Lewis acid (BF3, AlCl3, SnCl4, ZnCl2) combined with an alkyl halide (e.g., 2chloro-2-phenylpropane) co-initiator will form the initial carbocation. Polymerization then

proceeds by electrophilic attack of the carbocation on the double bond. As per Markovnikov's

rule, the more stable (more substituted) carbocation is formed.

Cationic polymerization is unsuited for monomers like propylene, which forms 2 C+'s. Chain

transfer, i.e., hydride shift can occur from a polymer chain, forming a more stable, 3 C+ and

thus terminating the polymerization or causing branching. The 3 C+ is 12-15 kcal/mol more

stable than the 2 C+.

Problem: Write a complete mechanism for the polymerization of isobutylene initiated by

2-chloro-2-phenylpropane and SnCl4.

39

Chain-Growth by Coordination Catalysts and the Ziegler-Natta Process:

The first polymerization processes for polyethylene were high pressure, free radical

processes which required severe and dangerous reaction conditions, i.e., 200 MPa (2000 atm)

pressure and 180 - 200 C!

A major improvement began in 1954 when Karl Ziegler and Guilio Natta disclosed a lowpressure coordination polymerization process for the production of high density polyethylene, i.e.,

HDPE. Ziegler reduced titanium tetrachloride liquid to alkylated titanium () chloride (brown

precipitate) in a solution of diethylaluminum chloride and xylene (or diesel oil). Ethylene bubbled

into this suspension at room temperature and 1-4 atm. pressure yielded a linear polyethylene of

high molecular weight, sometimes as high as three million.

Since that time an avalanche of literature, mainly patents, describing catalyst systems for

the production of crystalline polyolefins has continued unabated. The coordination catalysts are

generally formed by the interaction of the alkyls of group to metals with halides and other

derivatives of transition metals in groups IV-VIII of the periodic table.

TiCl3, the most common Ziegler catalyst, is octahedrally coordinated except at the solid

surfaces where electroneutrality requires that chlorine vacancies exist. These pentacoordinate,

surface TiCl3 molecules are activated by alkyl exchange with Al Et3.

Et

Et

Cl2

Ti

Cl4

Cl1

Ti

Cl4

Cl1

Cl3

5-coordinated Ti ion

Et

Et

Cl2

Al Et 3

Cl

Al

Cl2

Cl

Cl4

Ti

+ Cl Al Et2

Cl1

Cl3

Cl3

active catalyst

In the preceding diagram the ions Cl1 and Cl4 are also held by a second Ti atom in the

crystal lattice of TiCl3 and are thus considered nonexchangeable. The fifth chloride ion is

replaced by an ethyl group. The resulting active catalyst is an incomplete octahedral structure

with four chloride ions anchored in the interior of the solid lattice. The ethyl group is attached by

a bond to the titanium and the sixth position is a vacant d-orbital.

Initiation:

In the generally accepted monometallic, anionic, coordination mechanism of Ziegler

polymerization, an alkene (ethylene) attaches itself to titanium by a bond. The cloud of the

alkene overlaps the empty d-orbital of the metal forming a complex. The titanium-alkyl bond is

weakened in a transition state, thus facilitating insertion of the alkene between the alkyl group and

the titanium atom via newly formed bonds.

40

Et

Et

Cl2

Cl4

Cl2

C2H4

Ti

Cl1

Cl3

active catalyst

Cl3

complex

Ti

Cl4

CH2

Cl1

CH2

Cl2

Ti

Cl4

CH2

Cl1

CH2

Cl2

CH2

Ti

Cl4

Et

Et

CH2

Cl1

Cl3

transition state

Cl3

new active centre

Like the foregoing initiation reaction, propagation involves repeated insertion of ethylene

monomer between the titanium-carbon bond. This propagation from the root is analogous to hair

growth but is opposite to free radical polymerization in which the polymer chain grows at the tip.

At low reaction temperatures (below 50 C) the polymer attains high molecular weight. Chain

termination is controlled either by increased polymerization temperature, which gives elimination, or by addition of hydrogen.

Termination by -elimination:

CH 3

CH 2

CH 2

Cl2

Cl 4

CH 2

H R

C

H

Cl2

Ti

Cl 4

CH 2

Cl1

Ti

+ CH 2

CHR

Cl1

Cl 3

Cl 3

-elimination

Termination by hydrogenation: (Cat = catalyst)

Cat

CH2CH2R

+

H2

Cat

H

+

CH2

CHR

Most efforts in catalyst research and development have concentrated on catalyst efficiency,

resulting in so-called second- and third-generation Ziegler processes. Catalyst efficiency was

raised from ca. 10 to more than 1000 kg HDPE/g Ti. This was accomplished by supporting the Ti

catalyst on magnesium-based substrates such as Mg(OH)Cl which affords a greater surface area of

activated titanium. Nonsupported magnesium-titanium catalysts, such as Mg(TiCl6), are also

highly efficient probably due to their high specific surface area.

Ziegler catalysis can be applied to varied systems to produce HDPE grades for all modern

requirements, including waxes of molecular weight of ca. 10,000 to ultrahigh molecular weight

HDPE (UHMW-HDPE) with molecular weight of several millions. Due to this versatility, Ziegler

polyethylene has acquired a leading commercial position throughout the industrialized world.

Over 60 109 pounds/year of PE are produced world wide using Ziegler-Natta catalyst processes.

Ziegler-Natta catalysts are also responsible for the development of isotactic and syndiotactic vinyl

polymers.

41

Stepwise (Step-Growth) Polymerization:

The second type of polymerization, after chain-reaction polymerizations (free radical anionic,

cationic, and coordination) is stepwise polymerization. Difunctional monomers with compatible

functional groups combine in stepwise fashion to form dimers, then tetramers, then octamers, etc.

Important step-growth polymers include nylons, polyesters, polyurethanes, epoxies and phenolics.

Stepwise polymerizations are performed by reacting two different monomers, i.e.,

A-R-A + B-R-B, where A and B are functional end groups which react with each other but not

with themselves. For example, poly(ethylene terephthalate), (PET), is a polyester produced by

reacting a diol (ethylene glycol) with a diacid (terephthalic acid) ...

Monomers of only one kind with the structure A-R-B will also polymerize by stepwise growth.

For example Nylon 6, [poly(6-aminohexanoic acid)], used in brush bristles, rope, and tire

cords, is produced by self-condensation of 6-aminohexanoic acid.

In stepwise polymerization, in the early stages of polymerization, all monomer reacts

producing all oligomeric (short) chains. This is because, according to simple probability, the

most abundant species (monomers) tend to react first. The formation of high molecular weight

chains does not occur until late in the reaction, i.e., past 99% conversion, when there is finally

a probability of larger chains reacting with each other. Thus only high-yielding reactants can

be used if high molecular weight product is desired. Furthermore, monomer is very important

because any impurities such as monofunctional molecules, added to the chain ends, deactivate

the chain ends and stop further growth.

Stepwise polymerization can be subdivided into two types ...

Condensation reactions, as in the examples above, are those which eliminate (condense

out) small molecules such as water, alcohol, halohydric acids, etc.

Step-Addition (Rearrangement) reactions, proceed without byproduct formation. For

example, diamines react with diisocyanates to produce polyureas without a byproduct; a

molecular rearrangement occurs during the reaction ...

Problem:

Draw the product of polymerization of 1,4-diisocyanatobenzene + 1,2-diaminoethane.

42

Ring-Opening (Ring-Scission) Polymerization:

Many cyclic compounds undergo ring opening reactions which lead to polymer formation.

Usually, the structural units (mers) of such polymers have the same composition as the monomer;

however, the ring-opening and subsequent poly-addition produces linear polymers. Ionic

initiation is usually effective in this polymerization type.

For example, ethylene oxide polymerizes to poly(ethylene oxide) ...

-Caprolactam polymerizes to Nylon 6 ...

Summary of Polymerization Types:

In addition to the 3 types of polymerization, described above, several miscellaneous types are

found such as oxidative coupling. However, these can generally be grouped into one of the three

main types. Oxidative coupling has an unusual redox initiation but then proceeds by a free radical

mechanism. Various special cases will be detailed as they are encountered in our study of specific

polymers later in this course.

The following table summarizes the main types of polymerization used for some important

polymers ...

Monomer

Radical

Cationic

ethylene

Anionic

Coordination

propylene

isobutylene

dienes

styrene

vinyl chloride

vinylidene chloride

vinyl fluoride

tetrafluoroethylene

vinyl ethers

vinyl esters

acrylic esters

acrylonitrile

43

Polymerization Methods (Techniques/Media):

In principle, a polymerization reaction can be carried out in the solid phase, the liquid phase, or

the gas phase. In practice, commercial scale polymerizations are almost always conducted in the

liquid phase.

Liquid phase polymerizations may be subdivided into four groups according to the nature of the

physical system employed. All of these variations find widespread use in industry.

1. Bulk (Mass) Polymerization:

Here the system is composed of only monomer and polymer (and possibly initiator but no

solvent). This is most commonly applied to stepwise polymerization reactions. The method