Relational business-to-business exchange

advertisement

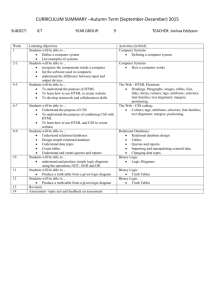

INTERIMISTIC RELATIONAL EXCHANGE: CONCEPTUALIZATION AND PROPOSITIONAL DEVELOPMENT C. Jay Lambe Assistant Professor of Marketing Texas Tech University Lubbock, TX 79409 806-742-3434 jlambe@coba.ttu.edu Robert E. Spekman Tayloe Murphy Professor of Business Administration Darden Graduate School of Business University of Virginia Charlottesville, VA 22906-3550 804-924-4860 SpekmanR@Virginia.edu Shelby D. Hunt The J.B. Hoskins and P.W. Horn Professor of Marketing Texas Tech University Lubbock, TX 79409 806-742-3436 sdh@ba.ttu.edu Revised October 1999 The authors are grateful for the financial assistance provided by the Darden Foundation. Also, we would like to thank the editor and three anonymous reviewers for their extremely helpful comments. In addition, we would like to thank Mike Wittmann, a doctoral student at Texas Tech University, for his help during the project. Please refer all correspondence to Jay Lambe, Assistant Professor of Marketing, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX 79409, 806-742-3434 (jlambe@coba.ttu.edu). INTERIMISTIC RELATIONAL EXCHANGE: CONCEPTUALIZATION AND PROPOSITIONAL DEVELOPMENT Abstract Research on relational exchange has focused primarily on long-term, or "enduring," relational exchange. The evolutionary model of relationship development that is the foundation for much of the research on enduring relational exchange lacks applicability for short-term, or "interimistic," relational exchange. Interimistic relational exchange is defined as a close, collaborative, fast developing, short-lived exchange relationship in which companies pool their skills and/or resources to address a transient, albeit important, business opportunity and/or threat. Because interimistic exchange relationships must quickly become functional and have a short life, these relationships have less time to fully develop the relational governance mechanisms assumed in the evolutionary model fashion. Therefore, interimistic relational exchange appears to rely more on non-relational mechanisms than does enduring relational exchange. This article (1) examines how interimistic relational exchange governance differs from that of enduring relational exchange and (2) develops propositions for further research on interimistic relational exchange. INTERIMISTIC RELATIONAL EXCHANGE: CONCEPTUALIZATION AND PROPOSITIONAL DEVELOPMENT I used to tell people that Internet years were like dog years. These days I feel as if Internet months are like dog years. The rate of change is stunning. -- Dan Rosen, Senior Director of Microsoft Network (Lyons 1996, p. 2,3) Business-to-business exchange of the “relational” (Macneil 1980) kind has special appeal to marketing researchers. At least since the works of Kotler (1972), Bagozzi (1975), and Hunt (1976), definitions of the process of marketing have been focused on exchange, which requires the establishment of some form of an exchange relationship between parties (Dwyer, Schurr and Oh 1987; Varadarajan and Cunningham 1995). Indeed, as business-to-business exchange has become increasingly relational in nature, some researchers argue that a paradigm shift from transactional to relational exchange is occurring (Day 1995; Kotler 1991; Parvatiyar, Sheth, and Whittington 1992; Varadarajan and Rajaratnam 1986; Webster 1992). This conclusion is reflected in a growing body of marketing research that focuses on relational, business-to-business exchange relationships (e.g., Dwyer, Schurr and Oh 1987; Gundlach and Murphy 1993; Morgan and Hunt 1994). Research on relational exchange suggests that a key mechanism that enables such exchange to create value, or that "governs" exchange, is the nature of the relationship. Thus, the development of a relationship whose nature has certain attributes is prerequisite to functional relational exchange. Specifically, such a relationship has high levels of such “relational” attributes as trust and commitment (e.g., Morgan and Hunt 1994). Research indicates that these relational attributes are developed through various stages over an extended period of time (Anderson and Weitz 1992; Dwyer, Schurr, and Oh 1987; Hakansson 1982; Hallen, Johanson, and Seyed-Mohamed 1991; Wilson 1995). Indeed, it can take up to four years for exchange partners to establish working norms (Spekman et al. 1994). Therefore, what might be called the “evolutionary model” of the process of 2 developing relational exchange suggests that high levels of relational exchange attributes are based on each partner’s historical, long-term view of the exchange relationship as it has developed through exchange episodes during the stages of relationship development. Most research has tended to focus on long-term or "enduring" relational exchange (hereafter, ERE), in which there is sufficient time for relational exchange to emerge in evolutionary fashion. In contrast, there is little research on short-term relational exchange even though numerous examples of such exchange relationships exist1. Although these short-term exchange relationships have little time to develop, they are genuinely relational because they exhibit high levels of cooperation and collaboration (Wilson 1995). We call these exchange relationships “interimistic” relational exchange (hereafter, IRE) because of their interim nature2. IRE is a close, collaborative, fast developing, short-lived exchange relationship in which companies pool their skills and/or resources to address a transient, albeit important, business opportunity and/or threat. In IRE, relational exchange occurs in a context where there is a high-level of time pressure to develop the relationship, and the expectation of future transactions is reduced. The paucity of research on IRE presents difficulties because "the dynamics of shorter relationships are different than those of longer relationships... [due to the fact that] longer relationships are qualitatively different than shorter ones, [therefore] there is value in research that focuses specifically on either type of relationship in order to understand better the dynamics of each" (Grayson and Ambler 1999, p. 139). In the case of IRE we argue that its exchange dynamics differ from that of ERE, because its short life makes the evolutionary model approach to relationship development less applicable. That is, ceteris paribus, IRE: (1) provides the exchange partners less time than does ERE to develop relational attributes in evolutionary fashion based on the given relationship's exchange history, which (2) causes certain relationship elements considered necessary 3 for functional relational exchange to exist at lower levels in IRE than in ERE and, thus, (3) forces firms in IRE to rely more on non-relational governance mechanisms than those in ERE. Therefore, this paper examines how urgency, or time pressure, to address a business situation affects the development of a functional exchange relationship in IRE. As a preliminary issue, however, it is important to note that our paper focuses on the time available for relationship-building interactions, not on the quality of the interactions that occur. The relational exchange literature provides (at least) three reasons for focusing on time (at least at this stage of theory development). First, though time in a relationship does not ensure relationshipbuilding interactions, it does limit, or bound, the number of interactions that can occur, high quality or otherwise. Thus, less time allows for fewer relationship-building interactions, which restricts the degree of relationship development. For example, Nevin (1995, p. 332) notes that early in an exchange relationship firms' interactions are restricted to "initial contracting agents" and are dominated by the substantial early issues that must be addressed to get the exchange off the ground. However, longer lasting relationships allow firms the time needed to get more individuals involved in the exchange relationship, and expand the number of norm-building interactions (Spekman et al. 1994). Second, research suggests that both the quality and quantity of interactions are important for relationship development. For example, research on one form of exchange interaction, communication, indicates that a key to relational exchange is both the frequency of communication and quality of communication (Mohr and Nevin 1990). As Weitz and Jap (1995, p. 314) note, "channel members who seek to restrict the relationship's development would tend to act in a restrained, polite manner, restrict the range of topics appropriate for discussion, and limit the frequency [emphasis added] of meetings." Third, "time-compression diseconomies" (Dierickx and Cool 1989) with respect to quality interactions occur in relationship development when exchange 4 relationships must develop quickly. In such relationships, Wilson (1995, p. 336) observes that the "stressful environment of relationship acceleration, ...[provides] less time for the participants to carefully explore the range of long-term relationship development." One example of such an exploration would involve time-consuming "tests" of exchange partners: In a channel relationship, a buyer might use an "endurance" test such as a decrease in purchases to gauge the depth of the distributor's commitment. Alternatively, the buyer might use a "triangle" test, in which a situation is created that involves a real or hypothetical alternative supplier that could replace the present supplier. This test allows the buyer to assess the supplier's loyalty to the relationship. A "separation" test may occur when the buyer discontinues contact for a period of time in order to monitor whether and when the supplier initiates interaction with the buyer. (Weitz and Jap 1995, p. 314) Our article is organized as follows. We begin by reviewing the literature on relational exchange, with a focus on relationship attributes and development. The review shows that the literature has implicitly emphasized ERE, leaving a gap with respect to IRE. Then, we develop propositions involving key relationship attributes and relationship development in IRE. These propositions, which show how firms engaged in IRE utilize non-evolutionary model mechanisms to ensure functional exchange, provide an agenda for future research. We end with some tentative conclusions and offer suggestions for future research. THE NATURE OF RELATIONAL EXCHANGE The study of relational exchange was initiated by researchers who began to explore a form of business-to-business exchange that represented a departure from the type of exchange that had dominated scholarly effort to that point, i.e., arms-length, transaction-oriented, adversarial exchange (Adler 1966; Arndt 1979; Hakansson 1982; Varadarajan and Rajaratman 1986). In a work that strongly influenced research in this new stream, Macneil (1980) developed a multidimensional typology of business exchange that differentiated traditional, arms-length business exchanges, which he deemed as "transactional" or discrete, from a new form of exchange that he named "relational." 5 In relational exchange, partners rely heavily on “relational contracts” to govern the exchange process (Macneil 1980). Such relational contracts are used when it becomes difficult for the involved parties to spell out the critical terms of a formal written contract (Goetz and Scott 1981). Indeed, the contract to the exchange becomes more relational as exchange contingencies and duties become less codifiable (Gundlach and Murphy 1993; Nevin 1995). To achieve the flexibility required in complex exchanges where there are unforeseen circumstances, relational exchange is marked by high levels of cooperation, joint planning, and mutual adaptation to exchange partner needs (Gundlach and Murphy 1993; Hallen, Johanson, Seyed-Mohamed 1991; Nevin 1995). Relational exchange is motivated by the mutual recognition that the outcomes of such exchange exceed those that could be gained from other forms of exchange or exchange with a different partner (Anderson and Narus 1984, 1990; Dwyer, Shurr, and Oh 1987; Nevin 1995). Significant research efforts have been directed at the strategic use of relational exchange (Gomes-Casseres 1987; Harrigan 1985a, 1985b, 1986, 1988), motivations for relational exchange (Heide and John 1990; Kogut 1988a, 1988b), the governance of relational exchange (Heide and John 1988, 1992), key relationship attributes of relational exchange (Ganesan 1994; Morgan and Hunt 1994), and the process of relationship development (Anderson and Weitz 1992; Dwyer, Schurr, and Oh 1987; Wilson 1995). Given our objective, we focus on the last two categories. Research on Functional Relational Exchange In relational exchange, the relationship is a critical governance mechanism and, therefore, a key determinant of relational exchange success. Simply put, functional relational exchange, i.e., exchange where relational contracts are highly effective, requires a functional relationship, i.e., a relationship that has high levels of such relational attributes as trust and commitment that help govern the exchange (Anderson and Narus 1984, 1990; Day 1995; Dwyer, Schurr, and Oh 1987; Heide and 6 John 1992; Morgan and Hunt 1994; Wilson 1995). Thus, recognizing the centrality of the relationship, researchers have attempted to pinpoint relationship attributes that must exist to ensure functional relational exchange, including: commitment (Anderson and Weitz 1992; Ganesan 1994; Morgan and Hunt 1994), trust (Moorman, Deshpande, and Zaltman 1992, 1993; Morgan and Hunt 1994), communication (Anderson and Narus 1990; Mohr and Nevin 1990), cooperation (Anderson and Narus 1990; Morgan and Hunt 1994; Stern and El-Ansary 1992), mutual goals (Heide and John 1992; Morgan and Hunt 1994), norms (Heide and John 1992), interdependence (Anderson, Lodish, and Weitz 1987; Anderson and Narus 1984, 1990; Hallen, Johanson, Seyed-Mohamed 1991), social bonds (Han, Wilson, and Dant 1993; Wilson 1995), adaptation (Hakansson 1982; Hallen, Johanson, Seyed-Mohamed 1991), and performance satisfaction (Dwyer, Schurr, and Oh 1987; Mohr and Spekman 1994; Wilson 1995). Research on relational exchange has also examined how these necessary relationship attributes are developed – or, in other words, the process by which functional relationships are developed. The preponderance of research views relationship development in relational exchange as a long-term, evolutionary process that is driven by intra-exchange relationship interactions between the partners over time (Anderson and Narus 1984, 1990; Anderson and Weitz 1992; Dwyer, Schurr, and Oh 1987; Hakansson 1982; Hallen, Johanson, and Seyed-Mohamed 1991; Heide and John 1992; Morgan and Hunt 1994; Spekman et al. 1996; Ring and Van De Ven 1994; Wilson 1995). In most cases, either explicitly or implicitly, these works rely on social exchange theory (SET) (Homans 1958; Thibault and Kelly 1959) to explain how firms are able to develop relationship variables (such as trust, cooperation, and commitment) to an extent where the partners can work together to make relational exchange successful. 7 For example, Dwyer, Schurr, and Oh (1987) suggest that buyer-seller relationships develop through buyer/seller interactions over an extended period of time. They argue that, as positive social and business outcomes occur, the partners develop relationship norms and become more dependent upon each other. Through these interactions, the firms in the exchange relationship pass through the relationship development stages of awareness exploration expansion before entering the commitment stage where the relational exchange attributes are highly developed. Similarly, Wilson (1995) proposes a process of relationship development in which exchange partners, through their interactions, develop such essential variables as trust. These attributes then act as a foundation for higher-level relationship variables, such as mutual commitment. Temporally Bifurcating Relational Exchange With respect to the exchange continuum suggested by Macneil (1980), all exchange relationships with a significant relational element are customarily lumped together as a monolith, "relational exchange". Thus, though Macneil’s (1980) typology views exchange as continuum, there has been little explicit examination of the relational continuum that exists within the presumed "relational exchange" category3. Since most exchange has at least some relational content, the need for research that examines relational exchange based on the degree of relationalism is warranted. As noted by Dwyer, Schurr, and Oh (1987, p. 12, 14): [D]iscrete exchange is idealized fiction...[E]ven the simplest model of discrete exchange must postulate what Macneil (1980) calls a 'social matrix': an effective means of communication, a system of order to preclude killing and stealing, a currency, and a mechanism for enforcement of promises. Hence, some elements of a 'relationship' in a contract law sense underlie all transactions. Given that the exchange continuum implies that relational exchange can be "more" or "less" relational, theorizing on the sources and consequences of such dispersion is needed. Therefore, a fundamental research question is: what are the variables that affect the degree of relationalism 8 exhibited by firms engaged in relational exchange? We propose that time pressure is a temporal variable that makes it more difficult and less desirable for firms to engage in relational exchange in its fullest sense. Because time pressure makes exchange less relational, we suggest that relational exchange be bifurcated into short-term and long-term relational exchange (or IRE and ERE, respectively). Figure 1 illustrates the bifurcation that we suggest. The continuum is based on Macneil's (1980) conceptualization of exchange. The left side of the continuum represents transactional exchange, the least relational of all exchange. The right side of the continuum represents relational exchange, the most relational of all exchange. The literature has already bifurcated transactional exchange into discrete (one-time, or "one shot") exchange and repeated transactions (Webster 1992). Although both forms of exchange are highly unrelational, repeated transactions are more relational than discrete because firms have a greater opportunity to develop a relationship. We suggest that a similar bifurcation exists for the right side of the continuum, relational exchange, with IRE being less relational than ERE because IRE allows for fewer interactions. [Insert Figure 1 About Here] Thus, although IRE is a form of relational exchange because it requires relatively high levels of cooperation, adaptation, and joint planning, the expected short life of IRE creates time pressure that makes it less relational than ERE. Because the exchange parties have limited time together, they are forced to eliminate, or accelerate, the evolutionary process of relationship development. The time compression diseconomies caused by IRE's expected short life stunt relationship development because they reduce the ability of the exchange parties to “view the relationship in terms of its history” (Dwyer, Schurr, and Oh 1987, p. 12), and reduce the parties' expectation of a future "mutuality of interest” (Heide and John 1992). In other words, partners have less time for the 9 evolution of relational attributes (such as trust and commitment) and relationship-specific norms (such as reciprocity). Indeed, Lusch and Brown (1996) show empirically that exchange relationships that have a “long-term orientation” exhibit more relational behaviors than those that do not. For example, during the advent of the personal digital assistant industry, Hewlett-Packard and Lotus formed an exchange relationship to create quickly (16 months) a personal digital assistant, which required that they "collaborate extensively," "work together smoothly," and manage their relationship in such a fashion as to "maximize the benefits of collaboration" (Gomes-Casseres and Leonard-Barton 1994, p. 37, 39). However, the same first-to-market time pressure also caused a high degree of market uncertainty that "made the commitment ...to each other less deep" (p. 46). Because IRE is less relational than ERE, we theorize that, compared with ERE, the development of functional IRE is less reliant on relational governance and more reliant on nonrelational governance. Thus, it would seem that transaction cost analysis (TCA) (Coase 1937; Williamson 1975, 1994) would play a significant role in explaining functional IRE because TCA is used to explain non-relational exchange governance. TCA views firms and markets as alternative forms of governance and suggests that exchange governance is driven by firms’ desire to minimize the direct and opportunity costs of exchange, i.e., "transaction costs" (Williamson 1975). Guided by its goal of transaction cost minimization, TCA attempts to explain why firms choose to use certain exchange relationship governance mechanisms based on the governance problem faced (Rindfleisch and Heide 1997). Governance problems, such as safeguarding relationship assets (Heide and John 1988) and/or ensuring partner adaptation (Heide and John 1990), can be thought of as TCA’s independent variables (Rindfleisch and Heide 1997). Governance mechanisms, such as vertical integration (Williamson 1975) or “pledges” (Anderson and Weitz 1992), can be thought of as TCA’s dependent variables (Rindfleisch and Heide 1997). 10 A basic premise of TCA is that the risk of partner opportunism limits the effectiveness of relational governance. However, several researchers have shown that, indeed, relational control in the form of norms or personal relations is often an effective means of governance (e.g., Anderson and Narus 1984, 1990; Dwyer, Schurr, and Oh 1987; Morgan and Hunt 1994; Wilson 1995). In addition, doubt has been cast on TCA’s assumption of universal opportunism, especially in relational exchange (e.g., Heide and John 1992; Morgan and Hunt 1994). Thus, TCA is limited in its capacity to explain exchange governance in exchange relationships in which the partners are able to develop relationship-based governance over time. Therefore, researchers of relational exchange have increasingly drawn on social exchange theory (SET), whose core explanatory mechanism is the relational contract that develops over time through the interactions of the exchange partners (Dwyer, Schurr and Oh 1987; Hallen, Johanson, and Seyed-Mohamed 1991). SET, though, has its own limitations, not the least of which is that, though theorists argue that relational contracts may serve as substitutes for formal contracts or direct control, the empirical evidence is limited and mixed (Rindfleisch and Heide 1997). For example, Heide and John (1992) show that relational norms by themselves have no effect on buyer control. Rather, relational norms act as a moderator of the link between dependence and control in exchange relationships. In addition, others have argued that contracts or direct control are necessary to serve as a “safety-net” should the relational contract temporarily fail -- which they might given the uncertainty in IRE (Ring and Van De Ven 1994). Consequently, one can argue that SET and TCA are complementary: both can help us understand certain aspects of relational exchange. Because one is not forced into an “either – or” situation, the question is not which theory to use, but to what degree and when one should use each theory. Thus, our propositions draw on both SET and TCA. 11 PROPOSITIONS ABOUT INTERIMISTIC RELATIONAL EXCHANGE The preceding section introduced the concept of IRE and the differences between it and ERE. Because our intent is to provide a platform from which additional research and empirical testing may take place, the hypotheses are designated as propositions. Although the propositions are grounded in theory and literature, some are unavoidably more speculative than others. Furthermore, we note that the variables in this section do not exhaust all possible relationship variables. We focus on them because (1) they have been consistently deemed important by researchers who study relational exchange, and (2) we posit that they are significantly affected by the temporal differences between IRE and ERE. Specifically, we focus on trust, interdependence, and relational norms (see Table 1). Trust and Substitutes for Trust Trust is a critical variable in relational exchange (e.g., Dwyer, Schurr and Oh 1987; Morgan and Hunt 1994; Wilson 1995). According to Morgan and Hunt (1994, p. 23), trust exists "when one party has confidence in an exchange partner's reliability and integrity." In the evolutionary model of relational exchange, trust is important because it acts as a relational governance mechanism assuring partner reciprocity and non-opportunistic behavior (Ganesan 1994; Morgan and Hunt 1994). For example, when mutual trust exists, parties in the exchange relationship have confidence that “unanticipated contingencies” will be resolved “in a mutually profitable manner,” rather than opportunistically (Ganesan 1994, p. 4). In addition, trust contributes significantly to the level of partner commitment to the exchange relationship (Moorman, Zaltman, and Deshpande 1992; Morgan and Hunt 1994; Wilson 1995). According to SET, the causal relationship between trust and commitment results from the principle of generalized reciprocity, which holds that "mistrust breeds mistrust and as such would also serve to decrease commitment in the relationship and shift the transaction to one of more direct short-term 12 exchanges" (McDonald 1981, p. 834). Mutual commitment is an important part of functional relational exchange because it ensures that partners will put forth the effort and make the investments necessary to produce mutually desirable outcomes (Dwyer, Schurr, and Oh 1987; Ganesan 1994). Although the evolutionary model of relational exchange implies that a high level of trust must exist to have functional relational exchange, it assumes that little to no trust exists at the beginning of the relationship, but develops through exchange episodes, or relationship interactions, over an extended period of time (Dwyer, Schurr, and Oh 1987; Wilson 1995). One way in which trust evolves is through mutual adaptations (Hallen, Johanson, and Seyed-Mohamed 1991). Adaptation occurs when one firm alters its processes and/or the products exchanged to accommodate the other party (Hakansson 1982). Through repeated interactions involving accommodations, each partner earns the trust of the other. In contrast, IRE allows partners less time for trust to evolve. Thus, we argue that the existence of trust in IRE relies strongly on variables that allow trust to develop either prior to, or very early in the life of, the exchange relationship. Three variables that would help firms engaged in IRE to overcome the time constraints on trust development are (1) prior extra-exchange relationship interactions, (2) a reputation for fair-dealing, and (3) pledges. As to prior extra-exchange relationship interactions, research indicates that positive past interactions with an exchange partner in other relationships contribute to trust in the exchange relationship in question (Ganesan 1994; Parkhe 1993). Specifically, past interactions lead to trust when partners feel satisfied with past outcomes and when they have had lengthy past associations (because these long-term associations term foster understanding). Thus, positive, prior, extraexchange relationship interactions can be used by firms prior to, or at the beginning of, IRE as signals that their exchange partner can be trusted (Weitz and Jap 1995). 13 As to a reputation for fair-dealing, it would also seem useful for trust-building in IRE because the trust it creates exists at the beginning of the relationship. An exchange partner's reputation for fair-dealing not only provides an important signal that the partner can be trusted, but also that the partner will do what is necessary to make the exchange relationship successful, for their reputations are "on the line". As noted by Anderson and Weitz (1992, p. 22), exchange partners "can signal their level of commitment through their...[reputation] in other...[exchange] relationships." Finally, pledges can also enable firms in IRE to create trust quickly because they are investments that can be made very early in the life of the exchange relationship (Ganesan 1994). Pledges are "actions undertaken by channel members that demonstrate good faith and bind the channel members to the relationship. Pledges are more than simple declarations of commitments or promises to act in good faith. They are specific actions binding a channel member to a relationship" (Anderson and Weitz 1992, p. 20). Relationship-specific investments are pledges that are "investments specific to a channel relationship[,]...are difficult or impossible to redeploy to another channel relationship...,[and] lose substantial value unless the relationship continues" (Anderson and Weitz 1992, p. 20). Relationshipspecific investments “provide a powerful signal” about the other party’s “credibility and desire to make sacrifices by investing in assets that are not easily redeployable elsewhere” (Ganesan 1994, p.10). Thus, relationship-specific investments contribute to trust because they represent a pledge that is viewed as a signal that the partner making the investments has benevolent intentions in the relationship. In summary, trust in IRE would appear to be heavily based on prior extra-exchange relationship interactions, a reputation for fair-dealing, and/or pledges, because these factors do not require intra-exchange relationship interactions over an extended period for their development. Given 14 the short life of IRE, the existence of trust in these relationships should be more reliant on these mechanisms to develop trust than in ERE where partners have more time to learn to trust each other through interactions in the exchange relationship in question. P1: Trust in IRE relies more on (1) prior extra-exchange relationship interactions, (2) reputation for fair-dealing, and (3) pledges than in ERE. Ceteris paribus, though, trust in IRE should be lower than in ERE. The rationale here is that unlike IRE, ERE can utilize both intra-exchange relationship interactions and a priori mechanisms to build trust. Therefore, because the intra-exchange relationship option of “trial and testing" (Wilson 1995, p. 340) is less available in IRE, trust should be lower in IRE than in ERE. P2: Trust is lower in IRE than in ERE. Recall that trust exists when a firm is confident that its exchange partner is reliable because of the partner's integrity. If functional IRE has lower levels of trust than ERE, then firms in IRE will have less of a sense that they can rely on their partner because of partner integrity. This observation is significant because the less a firm in an exchange relationship believes it can rely on the integrity of its partner, the less commitment it will have to the exchange relationship and, thus, the less likely it will put forth the effort and make the investments necessary to have successful, or functional, relational exchange. Therefore, the question arises: what do firms engaged in functional IRE use instead of the belief that they can rely on their trading partner's integrity? In other words, what do firms in functional IRE use as a substitute for trust? In TCA, Williamson (1994, p. 97) notes that substitutes for trust are: [C]redible commitments (through the use of bonds, hostages, information disclosure rules, specialized dispute settlement mechanisms, and the like)...[that create] functional substitutes for trust...Albeit vitally important to economic organization, such substitutes should not be confused with (real) trust. 15 When mutual substitutes for trust exist, they create mutual barriers to opportunistic behavior, which (1) allow firms in an exchange relationship to feel that they can rely on each other and (2) result in the firms exhibiting trust-like behaviors, i.e., behaving as if they trusted their exchange partner. As Rindfleisch and Heide (1997, p. 48) observe, trust-like behaviors on the part of a firm in an exchange relationship are based on the incentive structures of their trading partner(s) "that promote relationship-oriented behaviors or restrain opportunism." Substitutes for trust are especially important in IRE because they, unlike trust which requires considerable time to develop, can be developed quickly. For example, a fleeting business opportunity that requires collaboration and creates clear mutual dependence between exchange partners provides recognizable fair-dealing incentives that can be used immediately by the partners as substitutes for trust (Das and Teng 1998; Rindfleisch and Heide 1997; Rousseau, et al.1998; Sheppard and Sherman 1998; Williamson 1994). Therefore, given that IRE provides less time than ERE for trust development, ceteris paribus, IRE should rely more on substitutes for trust than ERE to create the trust-like behaviors that are necessary for functional relational exchange. P3: Reliance on substitutes for trust to promote trust-like behaviors is higher in IRE than in ERE. Three variables that could serve as substitutes for trust in IRE are environmental incentives, reputation, and relationship-specific investments (Anderson and Weitz 1992; Rindfleisch and Heide 1997; Stump and Heide 1996; Zajac and Olsen 1993). First, consider environmental incentives. Environmental conditions in the form of mutual business threats and opportunities can create substitutes for trust within an exchange relationship. (Varadarajan and Cunningham 1995). These include entering new international markets, protecting competitive position in home-market, shaping industry structure, entering new product domains, gaining a foothold in emerging industries, and acquiring new skills. Fierce competition for resources or a market from other companies or networks 16 of firms provides exchange partners with strong incentives to work together in good faith (Rindfleisch and Heide 1997; Lambe and Spekman 1997). From a resource dependence perspective, the partners are dependent upon each other for their success, and this dependence motivates them to cooperate and behave non-opportunistically (Pfeffer and Salancik 1978). In addition, IRE is particularly appropriate when a high degree of environmental uncertainty exists because, as Varadarajan and Cunningham (1995 p. 284) note, "when unstable market conditions prevail, such as is the case when the technological base of an industry is evolving rapidly, the flexibility and adaptability offered by less rigid forms of ...[relational exchange] may be viewed favorably." Environmental uncertainty also poses a problem for contracts in that partners lack the ability to write a contract that can cover all contingencies and ensure proper adaptation by the partners to changing conditions (Gundlach and Murphy 1993). The contractual limitations caused by environmental uncertainty heighten the mutual realization of the exchange partners that in order for them to "to achieve their mutual goals,” they must “conduct themselves in an ethical manner” to encourage such behavior from their partners (Gundlach and Murphy 1993, p. 41). Thus, substitutes for trust are created by environmental uncertainty because the partners should sense that if they display opportunism, or fail to act equitably, the relationship will not work Second, consider a reputation for fair-dealing. Such a reputation, as previously discussed, may signal that the party has high integrity and, therefore, is trustworthy. However, it may also serve as a substitute for trust because it can be thought of as an asset that provides incentives for firms that possess it to behave as if they were trustworthy (Ganesan 1994; Jones, Hesterly, and Borgatti 1997; Rindfleisch and Heide 1997). Firms having this asset are hesitant to damage it by acting opportunistically because a reputation for fair-dealing (1) takes a long-time to develop and (2) requires significant investment. Therefore, as Anderson and Weitz (1992, p. 22) suggest, "By making 17 sacrifices and demonstrating concern in other long-term relationships, channel members develop a reputation for operating effectively in quasi-integrated relationships. Such a reputation reduces the motivation of a channel member to act opportunistically, because such action would reduce the value of the reputation asset." Third, consider relationship-specific investments. In addition to being a potential signal of an exchange partner's trustworthiness (Anderson and Weitz 1992), relationship-specific investments may also serve as substitutes for trust because they are incentives for the firms that have made these investments to act non-opportunistically (Heide and John 1988; Stump and Heide 1996). These "idiosyncratic assets" (Anderson and Weitz 1992, p. 20) are non-fungible in nature and would be lost if the relationship were to terminate. Relationship specific assets may be tangible, such as a joint manufacturing facility, and/or intangible, such as a computer distributor who trains personnel to repair a specific brand of computer (Anderson and Weitz 1992). These relationship-specific assets increase the cost of terminating the exchange relationship and motivate partners to act nonopportunistically (Heide and John 1988, Stump and Heide 1996). Although all three are capable of functioning as substitutes for trust, IRE might rely less on relationship-specific investments than on the other two substitutes for trust for two reasons. First, fears of a short-lived exchange relationship should cause partners to make fewer relationship-specific investments. Rational partners in IRE should be hesitant to make relationship-specific investments because the exchange relationship may not last long enough to provide a pay-back on these investments (Bucklin and Sengupta 1993; Heide and John 1990; Stump and Heide 1996). Therefore, partners will likely attempt to keep relationship-specific investments at the minimum necessary for functional exchange. 18 Second, though relationship-specific investments may occur at the beginning of any exchange relationship, such investments also may be made over the life of an exchange relationship. Examples of relationship-specific investments that are made over time include: expanding joint manufacturing capabilities, improving the ability of the firms to work well together, keeping employees' knowledge current on the other firm's products, updating a just-in-time inventory system, and entwining a manufacturer and retailer in consumers' perceptions through promotions (Anderson and Weitz 1992; Dwyer, Schurr and Oh 1987; Heide and John 1988; Morgan and Hunt 1994). Because IRE provides less time for relationship-specific investments, ceteris paribus, IRE will have lower levels of relationship-specific investments than ERE. Thus, we argue that IRE should rely less on relationshipspecific investments as substitutes for trust than on environmental incentives and reputation. P4: Relationship-specific investments are less important than either reputation or environmental incentives as substitutes for trust in IRE. Interdependence Interdependence is the recognition by both partners in an exchange relationship that the relationship provides benefits greater than either partner could attain alone (Mohr and Spekman 1994), or that outcomes obtained from the exchange relationship are greater than those possible from other business alternatives (Anderson and Narus 1984, 1990; Dwyer, Schurr, and Oh 1987; Thibaut and Kelly 1959). The existence of mutual substitutes for trust creates interdependence in exchange relationships. How substitutes for trust create "outcome" interdependence is illustrated by environmental incentives, such as a mutual business opportunity or threat. Here, exchange partners are dependent upon each other for their success and, thus, if the firms are to achieve their individual goals their partners must achieve their goals also. Because it fosters a cooperative effort between the exchange partners, interdependence is important for functional relational exchange. Indeed, research suggests that interdependence is critical for promoting cooperation and adaptation in relational 19 exchange (Hallen, Johanson, and Seyed-Mohammed 1991; Kumar, Scheer, Steenkamp 1998), and a key contributor to partner commitment (Dwyer, Schurr, and Oh 1987; Morgan and Hunt 1994). The evolutionary model views interdependence as something that is built over a protracted period of time as the partners (1) invest in the exchange relationship, (2) determine mutually compatible goals, and (3) see positive outcomes from the relationship. The developmental stages that lead to fully functional relational exchange have a variety of nomenclature, e.g., “exploration and expansion” (Dwyer, Schurr, and Oh 1987), defining "purpose" and setting "boundaries” (Borys and Jemison 1989), "defining purpose and setting relationship boundaries” (Wilson 1995), and “vision/values/voice” (Spekman, et al. 1996). In the early stages of the evolutionary model of relational exchange, exchange partners see the potential to achieve outcomes that are superior to what they could achieve alone, but also must move through a series of developmental stages before a highlevel of interdependence emerges. The evolutionary model's view of interdependence-building is problematic for IRE because IRE has less time to build interdependence in a such a stages fashion. The short life of IRE and its heavy reliance on substitutes for trust imply that interdependence must emerge very early in the life of the relationship to ensure functional IRE. P5: Interdependence, the mutual recognition of mutual benefits, emerges earlier in IRE than in ERE. Relational Norms Norms are expectations about behavior that are at least partially shared by a group of decision-makers (Heide and John 1992). Norms are important in relational exchange because they provide the governance "rules of the game". These "rules" depend on the "game," which from an exchange perspective has been described as either discrete or relational (Macneil 1980). Discrete exchange norms contain expectations about an individualistic or competitive interaction between 20 exchange partners. The individual parties are expected to remain autonomous and pursue strategies aimed at the attainment of their individual goals (Heide and John 1992). In contrast, relational exchange norms “are based on the expectation of mutuality of interest, essentially prescribing stewardship behavior, and are designed to enhance the wellbeing of the relationship as a whole” (Heide and John 1992, p. 34). In the evolutionary model of relational exchange, relational norm development takes place over an extended period of time through many interactions between the partners (Hakansson 1982; Frazier and Anita 1995; Ring and Van de Ven 1994; Wilson 1995). For example, Dwyer, Schurr, and Oh (1987) suggest that tacit relational norms emerge as partners interact during the exploration stage of relationship development. The evolutionary model view of relational norm development poses difficulties for explaining IRE relational norm development. Clearly, for the IRE to be functional the partners need to have relational norms that will foster collaboration. Again, though, it appears that IRE does not have time (and certainly has less time) for norms to develop through intra-exchange relationship interactions. Therefore, IRE appears to be heavily reliant upon mechanisms that could develop mutual relational norms either prior to the initiation of the relationship, or very early in the life of the relationship. Three such mechanisms include: (1) industry-wide exchange norms, (2) the partners' mutual relational exchange competence, and (3) past extra-exchange relationship interactions. As to industry-wide exchange norms, a generally accepted set of norms for IRE is often available to the exchange partners because of the culture of the industry (Gulati, Khanna, and Nohria 1994; Jones, Hesterly, and Borgatti 1997). For example, firms in certain industries, such as biotech and high technology, have a tradition of IRE that is absent in firms in such industries as oil and chemicals, which tend to have longer product and exchange relationship life-cycles. In Silicon Valley, where non-proprietary and non-exclusive exchange relationships appear to be widely 21 accepted, companies have developed sets of norm-governed behaviors regarding IRE (Economist 1997). The clan-like culture established by these firms enables managers to migrate from company to company, bringing their past experiences, expectations, and contacts with them (Ouchi 1980). This environment has developed its own ecosystem, with a unique set of rules and an almost incestuous set of linkages among managers who have worked together and left either to form start-ups or work for other Silicon Valley firms (Bahrami and Evans 1995). Key managers move from start-up to start-up and take relationships with them that further establish a set of industry-specific norms. As to a relational exchange competence, such a competence helps partners short-cut the norm development process and provides opportunities for a less experienced firm to model the behavior of its more experienced partner. As described by Day (1995, p. 299), firms that have a relational exchange competence: have a deep base of experience that is woven into a core competency that enables them to outperform rivals in many aspects of...[relational exchange] management. They have well-honed abilities in selecting and negotiating with potential partners, carefully planning the mechanics of the...[relationship] so roles and responsibilities are clearcut, and continually reviewing the fit of the...[relationship] to the changing environment. A relational exchange competence hastens norm development because firms having such a competence will (1) more likely choose partners who will abide by relational norms, and (2) understand themselves the value following relational norms (Weitz and Jap 1995). In addition, firms that have a high capacity to learn and evidence a level of adaptability (Senge 1990) will be more attuned to the norm development process. We argue that firms that have a relational exchange competence have evidenced a high level of learning capacity and can learn through fewer interactions the norms that will maximize relational exchange outcomes. As to past extra-exchange relationship interactions between the exchange partners (Oliver 1990; Weitz and Jap 1995), because norms develop through interactions over time, such interactions 22 could contribute to IRE norm development and significantly shorten the process of such development. Indeed, if the previous dealings involved enough of the boundary personnel in the present IRE relationship and were extensive enough, the relationship’s norms could be almost fully developed prior to the initiation of the relationship. In short, there are industry and firm specific mechanisms that might allow partners in IRE to eliminate much of the intra-exchange relationship norm development process suggested by the evolutionary model of relational exchange. Three that appear to be useful for norm development in IRE are industry-wide exchange norms, a relational exchange competence, and past extra-exchange relationship interactions. P6: Relational norms emerge earlier in IRE than in ERE. P7: Compared with ERE, relational norm development in IRE relies more on (1) industrywide exchange norms, (2) relational exchange competence, and (3) past extra-exchange relationship interactions. Although relational norms should emerge earlier in IRE than in ERE, the dimensions of the relational norm construct imply that ERE ultimately should exhibit a higher degree of relational norms than IRE. Research suggests that the three dimensions of the relational norm construct are flexibility, information exchange, and solidarity (Noordewier, John, and Nevin 1990). Specifically: Flexibility defines a bilateral expectation of willingness to make adaptations as circumstances change …Information exchange defines a bilateral expectation that parties will proactively provide information useful to the partner…Solidarity defines a bilateral expectation that a high value is placed on the relationship. It prescribes behaviors directed specifically toward relationship maintenance. (Heide and John 1992, p. 35, 36) Based on the dimensions of the relational norm construct, IRE would appear to be less relational than ERE (see Figure 1), because it should score lower on the dimensions of information exchange and solidarity than ERE. Partners in IRE have the expectation that the relationship will be 23 short-lived and, in certain situations, the ending of the exchange relationship might find the former partners becoming competitors. These potentialities would seem to decrease the level of solidarity and information exchange in IRE in two ways. First, given the expectation of a short life, partners in IRE would seem to harbor less of a sense of continuity about the relationship and consequently would exhibit a lower level of stewardship behavior and/or solidarity. Second, since many IRE relationships might be classified as “co-opetition," because firms that are exchange partners now might later compete, partners in IRE might restrict the flow of information because they fear that some of the information that they share now might be used against them later (Brandenburger and Nalebuff 1996; Hamel and Prahalad 1994; Hamel, Dos, and Prahalad 1989). P8: IRE exhibits lower levels of relational norms than ERE. CONCLUSION Because research on IRE is in its early stages and, so far at least, strictly conceptual, implications must be considered highly tentative. However, examining the potential implications of the propositions (should they be confirmed by later research) is warranted. We suggest that researchers and managers begin to think more about relational exchange from a temporal perspective. Specifically, researchers need to develop a model of relationship development that is appropriate for IRE. In addition, it appears that IRE needs to be managed differently than ERE. A New Model Assuming that empirical research confirms the validity of the propositions above, the evolutionary model of relationship development does not explain how an IRE relationship develops a working and functional relationship. This would point to the need for researchers to develop a model that is appropriate for IRE. Based on the propositions above, it would appear that an important mix of antecedents that enable a functional IRE relationship are: interdependence based on environmental 24 incentives and reputation, relationship-specific investments, past extra-exchange relationship experience, and mutual relational exchange competence. These represent a reasonable starting point for the development of a non-evolutionary model of relational exchange. In this paper, trust and relational norms have been proposed to exist at low levels in functional IRE relative to the same variables in functional ERE. If these propositions are confirmed, evolutionary-model studies of relational exchange that have resulted in moderate or weak relationships between these variables and other variables may have been partially the result of the inclusion of IRE relationships in the sample. It might no longer be adequate to differentiate relational exchange by type (e.g., buyer-seller, horizontal, or joint R&D). It also might be useful to ascertain the temporal expectations of the exchange partners. Managing Interimistic Relational Exchange Different relational exchange contexts appear to require different managerial responses and different sets of expectations. Because of different temporal expectations about IRE, these exchange relationships would seem to require that partners play by a set of rules that is somewhat different from those applicable to ERE. In particular, boundary managers in IRE relationships should be prepared for the potentiality that, in some cases, their exchange partners may become their competitor at the conclusion of the exchange relationship. The question becomes: how can the exchange partners manage the existence of the seemly diametrically opposed roles of present collaborator and potential competitor without jeopardizing the collaborative spirit that must exist between the partners for functional IRE? As discussed, substitutes for trust provide much of the incentive for partners to work together non-opportunistically for the life of the exchange relationship and much of the assurance necessary for exchange partners to feel comfortable with this arrangement. Because IRE is not as relational as ERE, boundary managers should share information that is necessary to make the 25 exchange relationship work, but should be circumspect with other information. In addition, boundary managers should have a pre-planned exit strategy since it is expected that the exchange relationship will likely have a short life. Correspondingly, they should monitor both the environment and the exchange relationship for cues that the project is about to end. Also, scanning for and selecting exchange partners are critically important activities for IRE. As revealed in the propositions, two critical variables that should be requirements of any IRE partner are a reputation for fair-dealing and a relational exchange competence. Selecting an exchange partner with a fair-dealing reputation will reduce the risk of opportunism because (1) the reputation may be well-earned and (2) the exchange partner will not want to harm a reputational asset that it has spent time and money developing. Having an exchange partner with a relational exchange competence will help the partners short-cut the process necessary to establish the working norms necessary for functional IRE. Finally, if possible, it might be helpful to choose a partner with whom one has had substantial, satisfactory, extra-exchange relationship experience. Again, this will speed-up the norm development process and ensure a higher comfort-level between the exchange partners. In conclusion, there has been a tendency to view relational exchange as only a long-term proposition. Thus, the evolutionary model of relational exchange that has developed, while appropriate for ERE, cannot explain key aspects of IRE. Because of the time-pressure to develop and achieve goals, the exchange relationship characteristics associated with IRE are different from ERE and, thus, IRE warrants a different conceptual model. Such work holds the promise of great rewards, both for marketing theory and practice. This article begins the process of expanding our view of relational exchange to incorporate temporal considerations. 26 ____________________________ NOTES 1 For example, Day (1995 p. 297) notes that some relational exchange relationships "are deliberately short lived, lasting only as long as it takes one partner to enter a new market.” Similarly, Varadarajan and Cunningham (1995 p. 284) point out that some forms of relational exchange "will have a finite life by definition (e.g., a joint development project);” and relational exchange relationships "that do not involve shared equity are less rigid and may be easier to revise, reorganize, or terminate … As a result, when unstable market conditions prevail, such as is the case when the technological base of an industry is evolving rapidly, the flexibility and adaptability offered by less rigid forms of [relational exchange] may be viewed favorably.” 2 As a reviewer pointed out, on a firm-level, the concept of interimistic relational exchange is analogous to the organizational behavior concept of "coalitions" in which individuals in an organization form temporary alliances that last long enough to address a mutual opportunity or threat (Cobb 1991; Pearce 1995). 3 A notable exception is the research by Gundlach and Murphy (1993) that used the relational continuum that exists within contractual exchange to show how ethical principles become more important as exchange becomes more relational. FIGURE 1 The Exchange Continuum And Interimistic Relational Exchange _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Transactional Exchange Relational Exchange Discrete Repeated Exchange Transactions Interimistic Enduring Exchange Exchange TABLE 1 A Comparison of Enduring Versus Interimistic Relational Exchange Relationship Attribute Enduring Relational Exchange Interimistic Relational Exchange Expected Life-Span Long Short Business Opportunity/Threat Facing The Relationship Develops over time and is long-lasting. Immediate Trust Develops over time. Time limitations stunt the development of trust. Exchange partners are more reliant upon “substitutes for trust”. The trust that exists is based on the partners' reputation for fair-dealing, prior extra exchange relationship interactions, and/or signals from relationship-specific investments. Interdependence Evolves over time to a high-level. A high-level exists, and must emerge early in the life of the exchange relationship. Relational Norms Evolves over time to a high-level. A moderate-level exists because information exchange is more guarded, and because extant measures of relational norms capture the degree to which exchange partners have a long-term orientation. The relational norm development process is shortened by the existence of industry-wide exchange norms, partners who have a relational-exchange competence, and/or prior extraexchange relationship interactions. ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ REFERENCES Adler, Lee. 1966. “Symbiotic Marketing.” Harvard Business Review 44 (November-December), 5971. Anderson, Erin, Leonard M. Lodish, and Barton A. Weitz. 1987. “Resource Allocation Behavior in Conventional Channels.” Journal of Marketing Research 24 (February): 85-97. and Barton Weitz. 1992. “The Use of Pledges to Build and Sustain Commitment in Distribution Channels.” Journal of Marketing Research 29 (February): 18-34. Anderson, James C. and J. A. Narus. 1984. “A Model of the Distributor’s Perspective of DistributorManufacturer Working Relationships.” Journal of Marketing 48 (Fall): 62-74. and . 1990. “A Model of Distributor Firm and Manufacturer Firm Working Partnerships.” Journal of Marketing 54 (January): 42-58. Anonymous. 1997. “The Valley of Money’s Delight.” In Survey: Silicon Valley. Economist (March 29): 5-12. Arndt, Johan. 1979. “Toward a Concept of Domesticated Markets.” Journal of Marketing 43 (Fall): 69-75. Axelrod, Robert. 1984. The Evolution of Cooperation. New York: Basic Books. Bagozzi, Richard P. 1975. “Marketing as Exchange.” Journal of Marketing 39 (October): 32-39. Bahrami, Homa and Stuart Evans. 1995. “Flexible Re-Cycling and High-Technology Entrepreneurship.” California Review 37 (3): 62-89. Borys, Bryan and David B. Jemison. 1989. “Hybrid Arrangements as Strategic Alliances: Theoretical Issues in Organizational Combinations.” Academy of Management Review 14 (April): 234-249. Brandenburger, Adam M. and Barry J. Nalebuff. 1996. Co-opetition. New York: Doubleday. Bucklin, Louis P. and Sanjit Sengupta. 1993. “Organizing Successful Co-Marketing Alliances.” Journal of Marketing, 57 (April): 32-46. Coase, Ronald H. 1937. “The Nature of the Firm.” Economica N.S. 4: 386-405. Cobb, Anthony T. 1991. "Toward the Study of Organizational Coalitions: Participant Concerns and Activities in a Simulated Organizational Setting." Human Relation 44 (10): 1057-1080. Day, George S. 1995. “Advantageous Alliances.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 23 (4): 297-300. Das, T. K. and Bing-Sheng Teng. 1998. “Between Trust and Control: Developing Confidence in Partner Cooperation in Alliances.” The Academy of Management Review 23 (3): 491-512. Dierickx, Ingemar and Karel Cool. 1989. “Asset Stock Accumulation and Sustainability of Competitive Advantage.” Management Science 35 (December): 1504-1511. Dwyer, F. Robert, Paul H. Schurr, and Sejo Oh. 1987. “Developing Buyer-Seller Relationships.” Journal of Marketing 51 (April): 11-27. Frazier, Gary L. and Kersi D. Antia. 1995. “Exchange Relationships and Interfirm Power in Channels of Distribution.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 23 (4): 321-326. Ganesan, Shankar. 1994. “Determinant of Long-Term Orientation in Buyer-Seller Relationships.” Journal of Marketing 58 (April): 1-19. Goetz, Charles J. and Robert E. Scott. 1981. “Principals of Relational Contract.” Virginia Law Review 67 (September): 1089-1150. Gomes-Casseres, Benjamin. 1987. “Joint Venture Instability: Is It a Problem?,” Columbia Journal of World Business 22 (2): 97-102. and D. Leonard-Barton. 1994. “Alliance Clusters in Multimedia: Safety Net or Entanglement?” Unpublished paper presented at Colliding Worlds Colloquium at the Harvard Business School (October 6). Granovetter, Mark. 1985. "Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness." American Journal of Sociology 91: 481-510. Grayson, Kent and Tim Ambler. 1999. "The Dark Side of Long-Term Relationships in Marketing Services." Journal of Marketing Research 36 (February): 132-141. Gundlach, Gregory T. and Patrick E. Murphy. 1993. “Ethical and Legal Foundations of Relational Marketing Exchanges." Journal of Marketing 57 (October): 35-46. Gulati, R., T. Khanna and N. Nohria. 1994. “Unilateral Commitments and the Importance of Process in Alliances.” Sloan Management Review 35 (3): 61-69. Hakansson, Hakan. Ed. 1982. International Marketing and Purchasing of Industrial Goods: An Interaction Approach. Chichester, England: Wiley. Hallen, Lars, Jan Johanson, and Nazeem Seyed-Mohamed. 1991. “Interfirm Adaptation in Business Relationships.” Journal of Marketing, 55 (April): 29-37. Hamel, G. and C. K. Prahalad. 1994. Competing for the Future. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. Hamel, G., Y.L. Dos, and C. K. Prahalad. 1989. “Collaborate With Your Competitors.” Harvard Business Review 67 (1): 133-139. Han, Sang-Lin, David T. Wilson, and Shirish Dant. 1993. “Buyer-Seller Relationships Today.” Industrial Marketing Management 22 (4): 331-338. Harrigan, K. R. 1988. “Strategic Alliances and Partner Asymmetries.” Management International Review 28:53-72. . 1986. Managing for Joint Venture Success. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books. . 1985a. Strategies for Joint Ventures. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books. . 1985b. Strategic Flexibility. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books. Heide, Jan B. and George John. 1988. “The Role of Dependence Balancing in Safeguarding Transaction-Specific Assets in Conventional Channels.” Journal of Marketing 52 (January): 2035. and . 1990. “Alliances in Industrial Purchasing: The Determinants of Joint Action in buyer-Supplier Relationships.” Journal of Marketing Research 27 (February): 24-36. and . 1992. “Do Norms Matter in Marketing Relationships.” Journal of Marketing 56 (April): 32-44. Homans, George. 1958. “Social Behavior as Exchange.” American Journal of Sociology 63 (May): 597-606. Hunt, Shelby D. 1976. “The Nature and Scope of Marketing.” Journal of Marketing 40 (July): 17-28. Jones, Candace, William S. Hesterly, and Stephen P. Borgatti. 1997. “A General Theory of Network Governance: Exchange Conditions and Social Mechanisms.” Academy of Management Review 22 (4): 911-945. Kogut, Bruce. 1988a. “Joint Ventures: Theoretical and Empirical Perspectives.” Strategic Management Journal 9 (4): 319-332. . 1988b. “A Study of the Life Cycle of Joint Ventures.” MIR Special Issue: 39-52. Kotler, Phillip. 1972. “A Generic Concept of Marketing.” Journal of Marketing 36 (April): 46-54. . 1991. “Phillip Kotler Explores the New Marketing Paradigm.” Review Marketing Science Newsletter, Spring: 1, 4-5. Kotler, Phillip, Lisa K. Scheer, and Jan-Benedict E.M. Steenkamp. 1998. "Interdependence, Punitive Capability, and the Reciprocation of Punitive Actions in Channel Relationships." Journal of Marketing Research (May): 225-235. Lambe, C. Jay and Robert E. Spekman. 1997. “Alliances, External Technology Acquisition, and Discontinuous Technological Change.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 14 (2): 102-116. Lusch, Robert F. and James R. Brown. 1996. “Interdependency, Contracting, and Relational Behavior in Marketing Channels.” Journal of Marketing 60 (October): 19-38. Macneil, Ian. 1980. The New Social Contract, An Inquiry into Modern Contractual Relations. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. McDonald, Gerald W. 1981. “Structural Exchange and Marital Interaction.” Journal of Marriage and the Family (November): 825-839. Mohr, Jakki and Robert E. Spekman. 1994. “Characteristics of Partnership Success: Partnership Attributes, Communication Behavior, and Conflict Resolution Techniques.” Strategic Management Journal 15: 135-152. and John R. Nevin. 1990. “Communication Strategies in Marketing Channels: A Theoretical Perspective.” Journal of Marketing 54 (October): 36-51. Moorman, Christine, Rohit Deshpande, and Gerald Zaltman. 1993. “Factors Affecting Trust in Market Research Relationships.” Journal of Marketing 57 (January): 81-101. , Gerald Zaltman, and Rohit Deshpande. 1992. “Relationships Between Providers and Users of Marketing Research: The Dynamics of Trust Within and Between Organizations.” Journal of Marketing Research 29 (August): 314-29. Morgan, Robert M. and Shelby D. Hunt. 1994. “The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing.” Journal of Marketing 58 (July): 20-38. Nevin, John R. 1995. “Relationship Marketing and Distribution Channels: Exploring Fundamental Issues.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 23 (4): 327-334. Noordewier, Thomas G., George John, and John R. Nevin. 1990. “Performance Outcomes of Purchasing Arrangements in Industrial Buyer-Vendor Relationships.” Journal of Marketing 54 (4): 80-93. Oliver, Christine. 1990. “Determinants of Interorganizational Relationships: Integration and Future Directions.” Academy of Management Review 15 (2): 241-65. Ouchi, William G. 1980. “Markets, Bureaucracies and Clans.” Administrative Science Quarterly 25 (March): 129-41. Parkhe, A. 1993. “Strategic Alliance Structuring: A Game Theoretic and Transaction Cost Examination of InterFirm Cooperation.” Academy of Management Journal 36:794-829. Parvatiyar, Atul, Jagdish N. Sheth, and F. Brown Whittington, Jr. 1992. “Paradigm Shift in Interfirm Marketing Relationships: Emerging Research Issues.” Working paper, Emory University. Pearce, John A. II. 1995. "A Structural Analysis of Dominant Coalitions in Small Banks." Journal of Management 21 (November-December): 1075-1096. Pfeffer, Jeffrey and Gerald R. Salancik. 1978. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective. New York: Harper & Row. Rindfleisch, Aric and Jan B. Heide. 1997. “Transaction Cost Analysis: Past, Present, and Future Applications.” Journal of Marketing 61 (4): 30-54. Ring, Peter and A. Van De Ven. 1994. “Developmental Processes of Cooperative Interorganizational Relationships.” Academy of Management Review 19:90-118. Rousseau, Denise M., Sim B. Sitkin, Ronald S. Burt, and Colin Camerer. 1998. “Not So Different After All: A Cross-Discipline View of Trust.” The Academy of Management Review 23 (3): 393-404. Senge, Peter. 1990. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. New York: Doubleday. Sheppard, Blair H. and Dana Sherman. 1998. “The Grammars of Trust: A Model and General Implications.” The Academy of Management Review 23 (3): 422-437. Spekman, Robert E., Lynn A. Isabella, Thomas C. MacAvoy, and Theodore M. Forbes. 1994. “Strategic Alliances: A View from the Past and a Look to the Future.” In Relationship Marketing: Theory, Methods, and Applications, edited by J. N. Sheth and A. Parvatiyar. Atlanta, GA: Center for Relationship Marketing. , , , and . 1996. “Creating Strategic Alliances That Endure.” Long Range Planning 29 (3): 346-357. Stern, Louis W. and Adel I. El-Ansary. 1992. Marketing Channels. 4th ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc. Stump, Rodney L. and Jan B. Heide. 1996. “Controlling Supplier Opportunism in Industrial Relationships.” Journal of Marketing Research 33 (November): 431-441. Thibault, John W. and Harold H. Kelley. 1959. The Social Psychology of Groups. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Varadarajan, Rajan P. and Margaret H. Cunningham. 1995. “Strategic Alliances: A Synthesis of Conceptual Foundations.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 23 (4): 297-300. and Daniel Rajaratnam. 1986. “Symbiotic Marketing Revisited.” Journal of Marketing 50 (January): 7-17. Webster, Frederick E. 1992. “The Changing Role of Marketing in the Corporation.” Journal of Marketing 56 (October): 1-17. Weitz, Barton A. and Sandy D. Jap. 1995. “Relationship Marketing and Distribution Channels.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 23 (4): 305-320. Williamson, Oliver E. 1994. “Transaction Cost Economics and Organization Theory.” In The Handbook of Economic Sociology, edited by N. J. Smelser and R. Swedberg, 77-107. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. . 1975. Markets and Hierarchies: Analysis and Antitrust Implications. New York: Free Press. Wilson, David T. 1995. “An Integrated Model of Buyer-Seller Relationships.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 24 (4): 335-345. Zajac, Edward J. and Cyrus P. Olsen. 1993. “From Transaction Cost to Transactional Value Analysis: Implications for the Study of Interorganizational Strategies.” Journal of Management Studies 30 (1): 131-145. C. Jay Lambe is an assistant professor of marketing at Texas Tech University. Prior to entering academe, he was engaged in business-to-business marketing for both Xerox and AT&T. His research interests include business-to-business marketing, relationship marketing, marketing strategy, and sales management. He has publications in the Journal of Product Innovation Management, European Journal of Marketing, Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, and International Journal of Management Reviews. Robert E. Spekman is the Tayloe Murphy Professor of Business Administration at The Darden School. He was formerly Professor of Marketing and Associate Director of the Center for Telecommunications at the University of Southern California. He is a recognized authority on business-to-business marketing and strategic alliances. His consulting experiences range from marketing research and competitive analysis, to strategic market planning, supply chain management, channels of distribution design and implementation, and strategic partnering. Professor Spekman has taught in a number of executive programs in the U.S., Canada, Latin America, Asia, and Europe. He has edited/written seven books and has authored (co-authored) over 80 articles and papers. Professor Spekman also serves as a reviewer for a number of marketing and management journals as well as for the National Science Foundation. Prior to joining the faculty at USC, Professor Spekman taught in the College of Business at the University of Maryland, College Park. During his tenure at Maryland, he was granted the Most Distinguished Faculty Award by the MBA students on three separate occasions. Shelby D. Hunt is the J.B. Hoskins and P.W. Horn Professor of Marketing at Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas. A past editor of the Journal of Marketing (1985-87), and author of Modern Marketing Theory: Critical Issues in the Philosophy of Marketing Science (South-Western, 1991), he has written numerous articles on competitive theory, macromarketing, ethics, channels of distribution, and marketing theory. Three of his Journal of Marketing articles, “The Nature and Scope of Marketing” (1976), “General Theories and the Fundamental Explananda of Marketing” (1983), and “The Comparative Advantage Theory of Competition” won the Harold H. Maynard Award for the “best article on marketing theory.” He received the 1986 Paul D. Converse Award from the American Marketing Association for his “outstanding contributions to theory and science in marketing.” He received the 1987 Outstanding Marketing Educator Award from the Academy of Marketing Science and the 1992 American Marketing Association/Richard D. Irwin Distinguished Marketing Educator Award. His new and provocative book is entitled A General Theory Of Competition: Resources, Competences, Productivity, Economic Growth (Sage Publications, 2000).