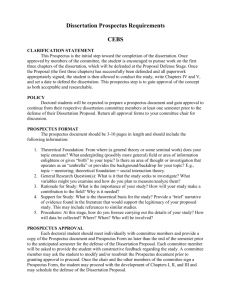

You should begin your prospectus with an introductory statement

advertisement

You should begin your prospectus with an introductory statement about the nature of the project which answers these questions: What is your dissertation topic? What central question(s) are you addressing? What hypotheses (if any) are you testing? The body of the prospectus goes into detail about the proposed research and answers three broad questions. 1. Can the project be done? 2. Is it worth doing? 3. What is the relationship of the research to scholarship in American Studies? Can the project be done? This is a question about sources, their nature, their accessiblility, and how they will be used. The prospectus should address the following in sufficient detail for your committee to understand how you propose to proceed, using what sources: 1. What are your sources? What kinds of evidence will you use? Are your sources accessible? Explain how your sources are adequate for completing the proposed research. Discuss any anticipated gaps in the sources or difficulties in using the sources. 2. What is your framework of inquiry and analysis? What theories or assumptions or both will organize your research processs and your interpretation of your sources? 3. How will you proceed? What methods will you use to examine, analyze, and “interrogate” your sources? What will your research process actually consist of? Where will it take place? What special tools or resources, if any, will you need to conduct your research? 4. How will you organize your findings? Include a tentative chapter outline and a rationale for that outline. Is it worth doing? What specific scholarly audience(s) are you addressing? What is the significance of the project: does it break new ground? Fill in a gap in the existing scholarly literature? Revise a previous interpretation? Or build and elaborate on previous interpretations? Include a brief review of the appropriate scholarly literature. Specify the particular scholarly contribution you hope to make to that literature. What is the relationship of the proposed research to scholarship in American Studies? Append a selected bibliography of primary sources and essential secondary references. Append a proposed timetable for completing the research and writing the dissertation. HISTORY harvard university Courses| Faculty| Undergraduate| Graduate| Resources| Calendar| Contact| Graduate Program > Requirements > Dissertation > Prospectus Under regulations of the revised graduate program approved by the Department in 1993, G-3s are required to present a written prospectus of the program they propose for the research and writing of a dissertation to their selected dissertation committee. The proposal should consist of 10 to 12 pages, with a select bibliography and a range of archives where the research will be conducted. In the course of developing the dissertation proposal, the candidate is expected to participate in a conference of faculty and graduate students, ordinarily held mid-year. Statement of Thesis What is the problem you wish to study and what is its interest or significance in current historical thinking? State clearly and concisely how you presently conceive of this problem and how you suppose it can be resolved. Historiographical Context What work has, and has not, been done in this field and on this problem? Discuss relevant scholarship critically. You need not belabor specific failings, which may sound tendentious; simply show what you understand to be the merits and limitations of relevant works. How do you propose to develop, challenge, or depart from existing positions or themes in historical literature? Method and Theory Outline an approach to your subject. If your conception has theoretical aspects, discuss these critically. Have scholars in other fields, historical or other, developed concepts of potential interest to your topic? In short, think carefully about method and theory, even if you decide not to engage much with external perspectives and theory. The faculty neither encourages nor discourages such engagement, but cautions that original historical work should not simply illustrate other people's ideas. Sources Give an account of the sources for your subject so far identified. Stress primary sources. What difficulties do they present? Where are they located, in print or manuscript (or in other forms)? Are they accessible? Identify the principal libraries and repositories as well as other locations and persons. Do not overlook unpublished doctoral or master's research. Schedule Draft a schedule of tasks and stages in which you plan to write the dissertation. Allow appropriate times for research, travel to collections, writing, and revision of draft chapters. Project, as nearly as possible, a chapter outline, which will be read in the understanding that prospective titles, chapters, and topics may change as you work. Bibliography List the primary and secondary sources used to develop your prospectus. WRITING A DISSERTATION PROSPECTUS prepared by Professors Ann Adams, Rainer Mack and Mark Meadow Department of the History of Art & Architecture University of California, Santa Barbara A dissertation prospectus is designed to be a useful tool, one which clarifies your project —its scope, subject matter, method, rationale — for yourself, for your dissertation committee and for potential sources of financial support. The prospectus should describe the questions your dissertation seeks to answer, describe the general field of research to which your project belongs and situate your work within that terrain. Specifically, it should describe how you will go about answering the questions you raise and explain the potential significance of the completed study to the field. working title for the dissertation. descriptive of the project. The text of a prospectus. overview what is interesting about it and the larger questions you will be pursuing. make your first statement about the consequences of your research for other scholars. any necessary background information to situate your work in relation to previous scholarship, though try to avoid setting up straw men. One productive strategy is to begin with a specific example of your subject matter, as for instance a particular image, building, or theory, and use a brief analysis to show your readers how the questions you are asking arise from the material itself. [Warde] Very important is clarity on the point of method. What questions will you be asking of your materials? How will you elicit answers? What models do you have in mind as you construct your study or build your thesis? The body of the prospectus should map the contours of the dissertation with brief discussions of each chapter or section. It is helpful to name the chapters and devote a paragraph or a page to the content of each. List the particular objects of study for each chapter and the main primary and secondary source material you will be using in pursuing that part of your project. When you write your prospectus, you will probably not yet have a full argument in hand, and certainly will not have mastered the full range of data. But the prospectus should make it clear that you do have a thesis, and some data relevant to it. It is helpful to keep in mind that the prospectus is just that, a prospective account of the project, and that your research will inevitably lead to modifications, sometimes radical, in your thesis. It is not unusual for the finished dissertation to contain material that was not part of the original prospectus. Appendices are often attached to the prospectus and contain relevant information not addressed in the main text. A bibliographic appendix is essential. This can either be a critical bibliography or a simple listing of primary and secondary sources. It can be arranged in a number of ways: alphabetically, chapter by chapter, thematically, or in whatever order best suits your subject matter and method. Another helpful appendix is a preliminary object list for the dissertation (with locations), which may include illustrations of selected objects. The object of the dissertation prospectus — beyond clarifying your own thinking — is to give your readers confidence that you have a good idea and a clear project in mind, that you know the field in question and that you have an orderly pattern for pursuing your research and organizing your findings. But most importantly, it gives you an opportunity to explain why your project is of consequence, and it permits your advisors to aid you effectively in achieving the best possible