Gender Differences in the Propensity to Depression and Anxiety

advertisement

Gender Differences in the Incidence of Depression and

Anxiety: Econometric Evidence from the USA+

Vani K Borooah*

University of Ulster

July 2009

Abstract

Using data from the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys (CPES) for the

United States for the period 2001-2003, this paper addresses a vexed question relating

to inter-gender differences in depression rates, namely how much of the observed

difference in depression rates between men and women may be explained by

differences between them in their exposure, and how much may be explained by

differences between them in their response, to depression-inducing factors. The

contribution of this paper is to propose a method for disentangling these two

influences and to apply it to US data. The central conclusion of the paper was

differences between men and women in rates of depression and anxiety were largely

to be explained by differences in their responses to depression-inducing factors: the

percentage contribution of inter-gender response differences to explaining the overall

difference in inter-gender probabilities of being depressed was 93 percent for “sad,

empty” type depression”; 92 percent for “very discouraged” type depression; and 69

percent for “loss of interest” type depression.

Keywords: Gender, depression, anxiety, decomposition.

JEL Classification: I1, I3

+

The data used in this paper are from the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys (CPES)

2001-2003 [United States] provided online by the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social

Research (ICPSR) http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/. I am grateful to three anonymous referees

whose comments have greatly improved the paper. However, I am solely responsible for its

deficiencies.

*

School of Economics, University of Ulster, Newtownabbey, Co. Antrim BT370QB, Northern Ireland,

United Kingdom (vk.borooah@ulster.ac.uk).

.

1. Introduction

Some economists are beginning to question a (arguably, the) fundamental

belief that underpins our subject, namely that a better economic performance by a

country is in itself, and of itself, a "good thing". (Frank, 1997, 1999; Layard, 2002,

2003).1 In response to such concerns, studies (both econometric and noneconometric) about the nature of happiness, and about the factors underlying

happiness, have mushroomed.2 Since a prominent conclusion of such studies is that

mental ill-health is a major reason for being unhappy, this study examines two

specific aspects of mental ill-health: depression and anxiety. 3

The reasons for the emphasis on depression and anxiety are three-fold. The

first is the large number of people who are affected by these two ailments: the

Psychiatric Morbidity Survey (2000) estimates that 6 million persons in the United

Kingdom suffer from depression or anxiety or both, with 14.4 million persons

suffering similar disorders in the USA. The second reason is that depression and

anxiety, by preventing many of its afflicted citizens from working, may impose large

economic costs on a country: Layard (2006) estimates that the loss in output in the

UK due to depression and anxiety is some £12 billion (or 1 per cent of the UK’s

national income) per year. Lastly, there is a significantly large gender bias to

depression and anxiety with women being much more likely than men to have these

conditions: meta-analysis of studies conducted in various countries show that women

1

For a public policy approach to the pursuit of happiness see Marks (2004).

Inter alia Blanchflower and Oswald (2000); Clark (1996, 1999, 2001); Clark and Oswald (1994);

Easterlin (1974, 1995, 2001); Frank (1985; 1997, 1999); Frey and Stuzer (2002); Hirsch (1976);

Layard (2002, 2003); Oswald (1997); Scitovsky (1976).

3

For example, Borooah (2006) in a study of Northern Ireland reported that only four percent of those

with severe mental health problems described themselves as happy and 60 percent described

themselves as unhappy; equally tellingly, only 32 percent of those whose mental health problems were

not severe described themselves as happy - the same proportion as those with severe heart problems

who regarded themselves as happy.

2

1 .

are roughly twice as likely as men to suffer depression (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1990;

Weissman et. al., 1996).

Indeed, it is the unequal distribution of depression and anxiety between men

and women that is the focus of this paper. There is a large literature on differences

between men and women in their propensities to be depressed and Culbertson (1997),

Piccinelli and Wilkinson (2000), Nolen-Hoeksema (2001) and Murakami (2002) inter

alia provide a good perspective to this body of work. In explaining why rates of

depression are higher for women than for men, Nolen-Hoeksema (2001) distinguished

between two effects, the quantification of which constitutes the fundamental purpose

of this paper.

First, she argued that, compared to men, women might be more likely to be

exposed to depression-inducing factors. So, for example: women were more likely

than men to be the victims of childhood sexual assault; they were more likely to be

trapped in the role of perpetual carers, with their lives sandwiched between caring for

their young children and their aged parents; they were more likely to be unequal

partners in heterosexual relationships with major, life-changing decisions being made

by their male partners; and they were more likely to do atypical and non-standard type

work exemplified by temporary or part-time jobs.4

Second, even when men and women were exposed to the same depressioninducing factors, women might be more likely than men to develop depression. This

might be due to gender differences in the response to such factors caused inter alia

by: biological factors;5 differences in levels of self-esteem between men and women;6

4

On this last point, see Mangan (2000).

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis plays a major role in regulating stress responses and,

compared to men, women are more likely to have a dysfunctional HPA responses to stress (Weiss et.

al. 1999)

5

2 .

differences between men and women in their respective propensities to introspection

and rumination.7

Given these two effects – engendered, respectively, by gender differences in

exposure, and in response, to depression-inducing factors – the need is for an

integrative model, encompassing both exposure and response effects, to explain

differences in depression rates between women and men (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2001).8

In addition, it would be useful to quantify how much of the observed difference in

depression rates between men and women could be explained by differences between

them in their exposure, and how much could be explained by differences between

them in their response, to depression-inducing factors. The central purpose of this

paper is to build such a model and offer such quantification.

2. The Data

The data used in this paper are from the Collaborative Psychiatric

Epidemiology Surveys (CPES) for the United States for the period 2001-2003. These

data, which are described in some detail in Alegria et. al. (2007), present inter alia

information on the prevalence of mental disorders and on the personal and social

circumstances of the respondents all of whom were 18 years or older. The CPES joins

together three nationally representative surveys: the National Comorbidity Survey

Replication (NCS-R); the National Survey of American Life (NSAL), and the

National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS); in consequence, CPES permits

analysts to approach analysis of the combined dataset as though it were a single,

nationally representative study.

6

With the consequence that conflicts in, or the ending of, relationships were more likely to produce

depression in women than in men.

7

A greater propensity to rumination in response to stress increases the risk of developing depression

(Noel-Hoeksema et. al., 1999).

8

Another possibility is that gender differences in depression rates may be the result of men responding

to stress through alternative modes such as antisocial behaviour and alcohol abuse (Kessler et. al, 1994;

Metzler et. al. 1995.

3 .

The CPES dataset is organised in different files, each relating to a particular

aspect of respondents’ lives, and from these files this paper focused on two: the

“Screening” and the “Demographic” files. The “Screening” and “Demographic”

instruments were administered to all the respondents in the survey; the instruments

pertaining to the other files were only applied to those affected by one or (more)

mental disorder. Using information from the Screening file, we defined a person as

having experienced depression if he/she answered “yes” to any of the following

questions:

(i)

Have you ever in your life had a period, lasting several days or longer,

when most of the day you felt sad, empty, or depressed?

(ii)

Have you ever in your life had a period, lasting several days or longer,

when most of the day you were very discouraged about how things were

going in your life?

(iii)

Have you ever in your life had a period, lasting several days or longer,

when you lost interest in most things you usually enjoy like work, hobbies,

and personal relationships?

Similarly, a person was defined as having experienced mild anxiety if he/she

answered the following question in the affirmative: have you ever in your life had an

attack of fear or panic when all of a sudden you felt very frightened, anxious, or

uneasy? By extension, severe anxiety was defined as answering yes to the following

question: Have you ever had an attack when all of a sudden you became very

uncomfortable, you either became short of breath, dizzy, nauseous, or your heart

pounded, or you thought that you might lose control, die, or go crazy?9

9

A problem with self-reported information is that of recall. If it is a natural instinct to suppress

memories of unpleasant events, and if the young are more likely to be susceptible to depression and

anxiety, then older persons in a sample are likely to "forget" that they were depressed or anxious when

4 .

For the NCS-R, a total of 9,282 adult interviews were completed: 7,963 with

the main respondent and 1,589 interviews with the second adult in the household; in

addition, 554 interviews were conducted with a sample of non-respondents using a

shortened version of the instrument. The final response rate was 70.9 percent for

primary respondents and 80.4 percent for secondary respondents. For the NSAL, the

overall response rate was 71.5 percent while, for the NLAAS, the response rate was

75.7 percent.10

<Table 1 about here>

Table 1 shows that 44 percent (of the 5,862 women analysed), compared to 35

percent (of the 4,227 men analysed), had felt “sad, empty, or depressed”; 44 percent

of women, compared to 38 percent of men, had felt “very discouraged”; 33 percent of

women, compared to 29 percent of men, had “lost interest in most things”; 40 percent

of women, compared to 32 percent of men, had experienced mild anxiety; and 10

percent of women, compared to 8 percent of men, had experienced severe anxiety.11

So, for every facet of depression and anxiety, women were more likely than men to

have experienced that condition with the gender gap being largest for feeling “sad,

empty, depressed” and for mild anxiety and smallest for “losing interest” and for

severe anxiety. Since the data refer to self-reported depression or anxiety, the

possibility is that gender differences in depression rates may be the result of men

responding to stress through alternative modes such as antisocial behaviour and

alcohol abuse (Kessler et. al, 1994; Metzler et. al. 1995).

they were young while, for the younger persons in the sample such memories are likely to be vivid.

Consequently, in a cross-section of people, older, compared to younger, respondents would report

lower rates of depression or anxiety purely for reasons of differences in recall.

10

Gender specific response rates were not provided.

11

The proportions were computed for persons who reported non-missing values for all the variables

used in the logistic regressions (Table 4-8): 10, 089 persons of whom 5,862 were women and 4,227

were men.

5 .

<Table 2 about here>

Table 2 shows the distribution of depression and anxiety by non-gender

attributes. The highest rates of depression and anxiety were for White persons ("sad":

50 percent), followed by Hispanics ("sad": 46 percent) and the lowest rates were for

Asians ("sad": 31 percent). People below the age of 30 had markedly higher rates of

depression and anxiety than the over 60s ("sad": respectively, 43 and 34 percent) and

those who were married or cohabiting ("sad": 35 percent) had markedly lower rates of

depression and anxiety compared to the never married or the

separated/divorced/widowed ("sad": 44 and 48 percent, respectively). Better-off

persons (those whose income-to-poverty line ratio was higher than the mean ratio)

had slightly lower rates of depression and anxiety ("sad": 39 percent) compared to

poorer persons12 ("sad": 41 percent).

Persons born in the USA were considerably more likely to have experienced

depression and anxiety, compared to non-US born persons, ("sad": 43 and 37 percent,

respectively) and persons living in the west of the USA ("sad": 36 percent) were

markedly less likely to have experienced depression and anxiety than persons living

elsewhere in the USA ("sad": above 40 percent). Rates of depression and anxiety were

impervious to education level but there was a strong link between such rates and

employment status: people who were unemployed had markedly higher rates of

depression and anxiety than those in employment ("sad": 47 and 39 percent,

respectively). This is consistent with much of the literature on the connection

between unemployment and depression (Clark and Oswald, 1994; Clark et. al., 2008).

However, the direction of causation is open to question: does unemployment cause

12

Those whose income-to-poverty line ratio was lower than the mean ratio

6 .

depression or are depressed persons more likely to be made unemployed? Böckerman

and Ilkmakunnas (2009), using panel data for Finland, suggest that persons with lower

levels of self-assessed health were more likely to become unemployed.

Compared to those in bad physical health ("sad": 54 percent), persons in good

physical health ("sad": 37 percent) - and, compared to those who had known

childhood trauma ("sad": 52 percent),13 persons who had not experienced childhood

trauma ("sad": 29 percent) - had much lower rates of depression and anxiety. Lastly,

there appeared to be a strong association between cognitive and social disability14 and

rates of depression and anxiety.

<Table 3 about here>

Table 3 shows the distribution of the attributes, noted above, between men and

women. Compared to the female part of the sample, a larger proportion of males

were: Asian (23 versus 18 percent); married (59 versus 45 percent); employed (73

versus 61 percent); lived in the West (30 versus 24 percent); and had an income-topoverty line score higher than the mean score. Also, compared to the female part of

the sample, a smaller proportion of males were: separated/divorced/widowed (16

versus 28 percent); unemployed (7 versus 9 percent); US born (54 versus 60 percent).

So, on all these counts, the gender distribution of attributes was biased towards higher

rates of depression and anxiety for women.

Conversely, compared to men: a larger proportion of women were Black (49

versus 40 percent) and a smaller proportion were Hispanic (25 versus 28 percent); and

a smaller proportion of women had experienced childhood trauma (46 versus 55

13

Childhood traumas were any of the following: fidgety childhood; frequently in trouble with adults

for six months or more during childhood or adolescence; lying, stealing as child or teenager; ran away

frequently, played truant, or stayed out late as child or teenager; had separation anxiety, for one month

or more, as a child.

14

Both of these were measured by a person’s World Health Organisation Disability Assessment Score

(WHO-DAS): the higher the score, the greater the disability.

7 .

percent). So, on all these counts, the gender distribution of attributes was biased

towards lower rates of depression and anxiety for women.

The preceding discussion raises two issues. First, what was the contribution of

each of the factors, listed in Table 2, to the likelihood of a person experiencing

depression and anxiety, after controlling for the other factors? Table 2, and the

discussion based on it, refer to the contributions in the absence of any imposed

controls. This question was answered in the context of an estimated logit model the

results from which are discussed in the next section. The second issue relates to the

aggregate contribution that differences in the distribution of the different attributes

between men and women made to gender differences in rates of depression and

anxiety. Section 4 addresses this question in the context of a decomposition model

originally developed by Blinder (1973) and Oaxaca (1973) for measuring

discrimination in the labour market.

3. Estimates from a Logistic Model of Depression and Anxiety

We estimated a logistic model for a dependent variable Yi such that Yi=1, if

the person (i=1…N) has had a condition (depression, anxiety), Yi=0, otherwise. The

model was estimated on a vector of variables, X ij being the value of the jth variable

for the ith person (j=1…J).15 A natural question to ask from the logistic model is how

the probability of having a particular condition would change in response to a change

in the value of one of the condition-affecting factors. These probabilities are termed

marginal probabilities.

For discrete variables, the marginal probabilities refer to changes in the

probabilities consequent upon a move from the residual category for that variable to

J

Pr(Yi 1)

exp{ X ij j } exp{zi } for J coefficients, βj and for

1 Pr(Yi 1)

j 1

observations on J variables.

15

The logit equation is

8 .

the category in question, the values of the other variables remaining unchanged. For

continuous variables, the marginal probabilities refer to changes in the probabilities

(of having the conditions) consequent upon a unit change in the value of the variable,

the values of the other variables remaining unchanged. Tables 4-6 show the

estimated marginal probabilities from the logistic model for, respectively: “felt sad,

empty depressed”; “felt very discouraged about how things were going in life”, and

“lost interest in most things one usually enjoyed” and Tables 7 and 8 show the

estimated marginal probabilities from the logistic model for, respectively, “mild

anxiety” and “severe anxiety”.

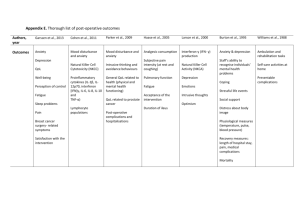

<Tables 4-8 about here>

The marginal probabilities are first shown for the model estimated over the

entire sample (10,087 persons: 5,861 women and 4,226 women) and then for the

model estimated over, respectively the female and male subsamples. The associated

z-values are shown alongside the marginal probabilities: a z value exceeding 1.96

indicates that the coefficient was significantly different from zero at a 5% significance

level. The rows of the table with typeface in italics are those variables for which the

difference between the female and male marginal probabilities was significantly

different from zero at the 20% (or less) level of significance.

So, for example, in Table 4, looking at the estimates obtained from the entire

sample, ceteris paribus the average probability of men having felt “sad, empty,

depressed” was 9.7 percentage points lower than that for women. The results

estimated across the female and male subsamples show that there were six statistically

significant (significance level: 20% or less) differences between women and men:

between Black women and men; between Hispanic women and men; between men

and women who were separated, divorced, or widowed; between employed women

9 .

and men; between women and men who had had childhood traumas; and between

women and men with respect to their WHO-DAS cognitive scores.

Compared to the probability of a white person having felt “sad, empty,

depressed”, the corresponding probability for a black person was ceteris paribus 12.2

points lower: row “Black”, column 2 of Table 4. However, compared to the

probability of a white woman having felt “sad, empty, depressed”, the corresponding

probability for a black woman was ceteris paribus 8.8 points lower and, compared to

the probability of a white man having felt “sad, empty, depressed”, the corresponding

probability for a black man was ceteris paribus 16.1 points lower: row “Black”,

columns 3 and 5, respectively, of Table 4. The results further suggest that the

marginal probability for black women (8.8 points) was significantly different from

that for black men (16.1 points).

A persistent feature of the results reported in Tables 4-8 was the importance of

race: ceteris paribus Asians, followed by Blacks, were much less likely to have

experienced depression and anxiety than White persons (see above discussion): see

Dunlop et.al. (2003). Another important feature of the results was marital status:

ceteris paribus compared to never married persons, separated/divorced/widowed

persons were more likely (in the case of feeling "sad, empty, depressed" by 5.8

points) to have experienced depression (though not anxiety). The effect of marital

status on depression, however, varied by gender: compared to never married men,

men who were separated/divorced/widowed were significantly more likely to have

experienced all three forms of depression ("sad, empty, depressed": 9.6 points; "very

discouraged": 7.8 points; "loss on interest": 9.7 points); compared to never married

women, women who were separated/divorced/widowed were significantly more likely

to have only experienced feeling “sad, empty, depressed” (by 4.3 points) without any

10 .

significant difference in the likelihood of feeling “very discouraged” or a “loss of

interest”.

A third feature of the results was the importance of childhood trauma in

determining whether a person, male or female, would experience depression and

anxiety as an adult: compared to their counterparts who had not known childhood

trauma, men and women who had were more likely, by approximately 22 percentage

points, to have experienced all three forms of depression and, by approximately 20

points, to have experienced mild anxiety.

4. Gender Decomposition of the Probabilities of Depression and

Anxiety

The Oaxaca (1973) and Blinder (1973) method (hereafter, O-B) of

decomposing differences between groups, in their respective mean values, into a

“discrimination” and a “characteristics” component is, arguably, the most widely used

decomposition technique in economics. This method has been extended from its

original setting within regression analysis, to explaining group differences in

probabilities derived from models of discrete choice with a binary dependent variable

and estimated using logit/probit methods (Nielsen, 1998).

The O-B decomposition (and its extension) is formulated for situations in

which the sample is subdivided into two mutually exclusive and (collectively

exhaustive) groups, such as, for example, men and women.

Then, one may

decompose the difference in, for example, average wages between men and women –

or the difference between men and women in their average probabilities of being

depressed – into two parts, one due to gender differences in the coefficient vectors

and one due to gender differences in the attribute (or variable) vectors.

The attribute contribution is computed by asking what the average malefemale difference in probabilities would have been if the difference in attributes

11 .

between men and women had been evaluated using a common coefficient vector. The

critical question though is: what should be this common coefficient vector?

Typically, two separate computations of the attribute contribution are provided using,

respectively, the male and the female coefficient vectors as the common vector.

<Table 9 about here>

Column 1 of Table 9 shows the difference between men and women in the

average proportions with a particular condition. On average, compared to men,

women were: more likely by 8.9 percentage points to have felt “sad, empty,

depressed”; more likely by 6.4 points to have felt “very discouraged”; more likely, by

3.9 points to have felt a “loss of interest”; more likely by 7.7 points to have had mild

anxiety; and more likely by 2.0 points to have had severe anxiety.

Column 2 of Table 9 shows the amount of the overall gap that is due to the

attributes effect when female and male attributes are both evaluated using female

coefficients; similarly, column 4 of Table 9 shows the amount of the overall gap that

is due to the attributes effect when female and male attributes are both evaluated using

male coefficients. Three points need to be made about the attributes effect:

1.

The size of the attributes effect differs according to whether female or male

coefficients are used in the evaluation. For example, for “loss of interest”

depression, the attributes effect based on female coefficients explains 15

percent – while the attributes effect based on male coefficients explains 44

percent - of the overall difference in inter-gender rates.

2.

For some conditions, the attributes effect predicts that, if male attributes were

evaluated at female coefficients, then, compared to women, a higher

proportion of men would have had that condition. Feeling “sad, empty,

12 .

depressed”, feeling “very discouraged”, and mild anxiety are three such

conditions.

3.

In general, the contribution of the attributes effect towards explaining the

overall difference in inter-gender rates was small. The largest contributions

were recorded when male coefficients were used in the evaluation of female

and male attributes and these were 16 percent for “very discouraged”

depression and 44 percent for “loss of interest” depression.

The problem with the O-B method of decomposition is that the decomposition

is anchored either by treating men as women (column 2, Table 9) or women as men

(column 4, Table 9). More recently, Borooah and Iyer (2005) have proposed a

method of decomposition which combines both “anchors” into a single decomposition

formula.

Denote, by P W and P M , the average probabilities of having experienced a

condition, computed over all the persons in the sample, when their individual attribute

vectors (the X ki ) are all evaluated using the coefficient vectors of, respectively

women ( βW ) and men ( β M ); in other words, P W and P M are the average probabilities

of having had a condition, computed over the entire sample, when all the persons in

the sample are treated as, respectively, women and men. The difference between the

probabilities, PW P M , represents the “response effect” because it is entirely the

consequence of differences between women and men in their (coefficient) responses

to a given vector of attributes.

Borooah and Iyer (2005) have shown that these synthetic probabilities can be

used to resolve the ambiguity of the O-B formulation since:

Y W Y M ( PW P M ) the weighted average of the two attribute effects

13 .

where the two attribute effects are shown in columns 2 and 4 of Table 9, the weights

being the proportions of women and men in the sample.

Column 7 of Table 9 shows the difference between women and men in their

synthetic probabilities of experiencing a particular condition. Remembering that these

differences represent inter-gender response differences, the percentage contribution of

such differences to explaining the overall difference in probabilities was: 93 percent

for “sad, empty” depression”; 92 percent for “very discouraged” depression; 69

percent for “loss of interest” depression; 116 percent for “mild anxiety”; and 80

percent for “severe anxiety”.

5. Conclusions

The contribution of this paper to the extensive literature on gender differences

in depression rates was to apply the Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition methodology to

quantifying the contribution of differences in exposure, and differences in response,

to inter-gender differences in depression rates. Needless to say, the division of the

sample could have been by factors other than gender and, in the context of depression

and anxiety, it might be useful to examine inter-racial differences in the propensity

towards these conditions. As the data in Table 2 shows, reported rates of depression

and anxiety are considerably lower for Asians than for Whites. Is this due to the fact

that Asians are, perhaps, relatively sheltered from depression/anxiety inducing

factors? That the sample of Asians contained relatively more males? Or is it because

Asian responses to such factors (these responses perhaps engendered by a Confucian

stoicism which makes it culturally less acceptable to admit to emotional frailty than

might be the case for those with liberal, Western roots) are relatively more muted than

the responses of people of other races? Similar observations might be made about

regional divisions: does living in sunny California offer greater protection from

14 .

factors associated with depression and anxiety compared to living in the rust belts of

the Mid West? Or are people living in California better able to cope with such

factors?

This paper offered a methodology - with a long and distinguished pedigree in

economics - which is capable of providing answers to questions in which

responsibility needed to be apportioned between exposure and response. However, it

might be pertinent to conclude this paper by pointing to a limitation of this

methodology. It should be emphasised that the response effect was defined as a

residual: it was what could not be explained by differences between men and women

in their exposure to the various "depression-influencing" factors. Consequently, the

empirical results are only as good as the variables used in the logit regression; with a

different set of variables the exposure/response split might have been different.

The relevance of this observation to the present analysis is that several of the

variables used could not be better nuanced. For example, marital breakdown was a

"depression-inducing" factor but the data were silent on the circumstances

surrounding the breakdown; similarly, differences between men and women in the

nature of their employment, or in the nature of their work-home balance, could not be

elaborated upon. These examples provide arguments for marrying mental health

information to a richer set of data on individual circumstances.

15 .

References

Alegria, Margarita, Jackson, J.S., Kessler, R.C., and Takeuchi, D. (2007),

Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys (CPES), 2001-2003 [United States]

[Computer file]. ICPSR20240-v5, Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research,

Survey Research Center [producer], 2007. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university

Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2008-06-19.

Blanchflower, D. and Oswald, A. (2002), Well-Being Over Time in Britain

and the USA, NBER Working Papers, no. 7487, Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau

of Economic Research.

Blinder, A.S. (1973), “Wage Discrimination: Reduced Form and Structural

Estimates”, Journal of Human Resources, vol. 8, pp. 436-455.

Böckerman, P. and Ilmakunnas, P. (2009). "Unemployment and Self-assessed

Health: Evidence from Panel Data", Health Economics, vol. 18, pp. 161-179.

Borooah, V.K. and Iyer, S. (2005, "The Decomposition of Inter-Group

Differences in a Logit Model: Extending the Oaxaca-Blinder Approach with an

Application to School Enrolment in India”, Journal of Economic and Social

Measurement , vol. 30, pp.279-93.

Borooah, V.K. (2006), “What Makes People Happy? Some Evidence From

Northern Ireland”, Journal of Happiness Studies vol. 7, pp. 427-65.

Clark, A.E. and Oswald, A. (1994), "Unhappiness and Unemployment",

Economic Journal, vol. 104, pp. 648-59.

Clark, A.E. (1996), "Job Satisfaction in Britain", British Journal of Industrial

Relations, vol. 34, pp. 189-217.

Clark, A.E. (1999), "Are Wages Habit Forming? Evidence from Micro Data"

Journal of Economic Behaviour and Organisation, vol. 39, pp. 179-200.

16 .

Clark, A.E. (2001), "What Really Matters in a Job? Hedonic Measurement Using

Quit Data", Labour Economics, vol. 8, pp. 223-242.

Clark A.E, Diener E, Georgellis Y, Lucas R. 2008, "Lags and leads in life

satisfaction: a test of the baseline hypothesis", Economic Journal vol. 118, pp. F222–

F243.

Culbertson, F.M. (1997), “Depression and Gender: An International Review”,

American Psychologist, vol. 52, pp. 25-31.

Dunlop, D.D, Song, J., Lyons, J.S., Manheim, L.M., and Chang, R.W., (2003)

"Racial/Ethnic Differences in Rates of Depression Among Preretirement Adults",

American Journal of Public Health , vol. 93, pp. 1945-1952.

Easterlin, R.A. (1974), "Does Economic Growth Improve the Human Lot? Some

Empirical Evidence", in P.A. David and M.W. Reder, Nations and Households in

Economic Growth: Essays in Honour of Moses Abramowitz, New York: Academic

Press.

Easterlin, R.A. (1987), Birth and Fortune: The Impact of Numbers on Personal

Welfare, Chicago: Chicago University Press (2nd edition).

Easterlin, R.A. (2001), "Income and Happiness: Towards a Unified Theory",

Economic Journal, vol. 111, pp. 465-484.

Frank, R.H. (1985), Choosing the Right Pond, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Frank, R.H. (1997), "The Frame of Reference as a Public Good", Economic

Journal, vol. 107, pp. 1832-47.

Frank, R.H. (1999), Luxury Fever: Money and Happiness in an Era of Excess,

Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Frey, B.S. and Stutzer, A. (2002), Happiness and Economics, Princeton, New

Jersey: Princeton University Press.

17 .

Hirsch, F. (1976), The Social Limits to Growth, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard

University Press.

Kessler, R.C, McGonagle, K.A, Zhao, S. et al. (1994), “Lifetime and 12-month

prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the

National Comorbidity Survey”, Arch Gen Psychiatry vol. 51, pp.8-19.

Layard, R. (2002), Rethinking Public Economics: Implications of Rivalry and

Habit, Centre for Economic Performance, London: London School of Economics.

Layard, R. (2003), Happiness: Has Social Science a Clue? Lionel Robbins

Memorial Lectures 2002/3, London: London School of Economics.

Layard, R. (2006), The Depression Report: A New Deal for Depression and

Anxiety Disorders, Centre for Economic Performance, London: London School of

Economics.

Mangan, J. (2000), Workers Without Traditional Employment: an International

Study of non-Standard Work, Cheltenhan: Edward Elgar.

Meltzer H, Gill B, Petticrew M, Hinds K (1995), OCPS Surveys of Psychiatric

Morbidity in Great Britain, Report 1: The prevalence of psychiatric morbidity among

adults living in private households, London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

Murakumi, J. (2002), “Gender and Depression: Explaining the Different Rates

of Depression between Men and Women”, Perspectives in Psychology (the

undergraduate Psychology journal of the University of Pennsylvania), vol. 5, pp. 2734.

Nielsen, H.S. (1998), “Discrimination and Detailed Decomposition in a Logit

Model”, Economics Letters, vol. 61, pp. 115-20.

Noel-Hoeksema, S. (1990), Sex Differences in Depression, Stanford CA: Stanford

University Press.

18 .

Noel-Hoeksema, S., Larson, J., and Grayson, C. (1999), “Explaining the Gender

Difference in Depression”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 77, pp.

1061-72.

Noel-Hoeksema, S. (2001), “Gender Differences in Depression”, Current

Directions in Psychological Science, vol. 10, pp. 173-76.

Oaxaca, R. (1973), “Male-Female Wage Differentials in Urban Labor Markets”,

International Economic Review, vol. 14, pp. 693-709.

Oswald, A. (1997), "Happiness and Economic Performance", Economic Journal,

vol. 107, pp. 1815-31.

Piccinelli, M. and Wilkinson, G. (2000), “Gender Differences in Depression”,

British Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 177, p. 486-92.

Scitovsky, T. (1976), The Joyless Economy, New York: Oxford University Press.

Weiss, E.L., Longhurst, J.G., and Mazure, C.M. (1999), “Childhood Sexual Abuse

as a Risk Factor for Depression in Women: Psychosocial and Neurobiological

Correlates”, American Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 156, pp. 816-28.

Weissman, M.M., Bland, R.C., Canino, G.J., Faravelli,C., Greenwald, S., Hwu,

H.-G., Joyce, P.R., Karam, E.G., Lee, C.-K., Lellouch, J., Lepine, J.- P., Newman,

S.C., Rubio-Stipc, M., Wells, E.,Wickramaratne, P.J., Wittchen, H.-U., & Yeh, E.-K.

(1996), “Cross-national epidemiology of major depression and bipolar disorder”,

Journal of the American Medical Association, vol. 276 , pp. 293–299.

19 .

Table 1

Proportion of Men and Women who have been Depressed/Anxious, by type of

Condition

Percentage who for a period

Men (4,227)

Women (5,862)

All persons

lasting several days or longer:

(10,089)

Felt sad, empty, or depressed

35

44

40.5

Felt very discouraged about

38

44

41.3

how things were going in life

Lost interest in most things they

29

33

31.6

usually enjoyed like work,

hobbies, and personal

relationships

Mild Anxiety

32

40

36.7

Severe Anxiety

8

10

7.9

Notes to Table 1:

Proportions were computed for persons who reported non-missing values for all the variables

used in the logistic regressions (Table 4-8): 10,089 persons of whom 5,862 were women and

4,227 were men.

Depression is defined as a positive response to any of the following questions

(iv)

Have you ever in your life had a period, lasting several days or longer, when most

of the day you felt sad, empty, or depressed?

(v)

Have you ever in your life had a period, lasting several days or longer, when most

of the day you were very discouraged about how things were going in your life?

(vi)

Have you ever in your life had a period, lasting several days or longer, when you

lost interest in most things you usually enjoy like work, hobbies, and personal

relationships?

Mild anxiety is defined as answering yes to the following question: Have you ever in your life

had an attack of fear or panic when all of a sudden you felt very frightened, anxious, or

uneasy?

Severe anxiety is defined as answering yes to the following question: Have you ever had an

attack when all of a sudden you became very uncomfortable, you either became short of breath, dizzy,

nauseous, or your heart pounded, or you thought that you might lose control, die, or go crazy?

20 .

Table 2: Distribution of Depression and Anxiety by Attribute

Sad

Discouraged Loss of

Percentage with the condition

interest

Overall sample

41

41

32

Race, Ancestry

Asian

31

32

24

Black

40

41

33

Hispanic

46

44

33

White

50

55

41

Age

Age: 18-30

43

46

36

Age:31-45

41

42

31

Age: 46-60

42

42

33

Age >60

34

31

22

Marital Status

Married or cohabiting

35

36

27

Separated, divorced, widowed

48

46

37

Never married

44

46

37

Resources (average score = 3.57)

Income-to-needs-ratio: hhinc/poverty line > mean

39

39

29

Income-to-needs-ratio: hhinc/poverty line < mean

41

42

33

Years of Education

Education high

40

41

30

Education Medium

41

43

35

Education moderate

40

41

31

Education low

41

40

30

Employment status

Employed

39

40

30

Unemployed

47

50

40

Inactive

43

41

34

Immigration status

US born

43

46

36

Non-US born

37

35

26

US region

North East

44

45

36

Mid West

45

48

38

West

36

37

28

South

41

41

31

Health, Childhood, Society

Good physical health

37

38

28

Bad physical health

54

54

44

Childhood traumas

52

55

44

No childhood trauma

29

28

19

Church member

39

40

31

No Church membership

41

42

32

Disability Scores

WHO-DAS: cognitive score> mean =1.19

76

80

72

WHO-DAS: cognitive score< mean =1.19

37

38

28

WHO-DAS: social interaction score > mean =0.85

78

81

76

WHO-DAS: social interaction score < mean =0.85

38

39

29

21 .

Mild

anxiety

37

Severe

anxiety

8

30

35

41

45

5

9

8

12

37

37

39

31

8

7

8

11

34

40

39

7

10

7

36

37

7

9

37

38

37

35

6

8

8

9

36

40

39

7

10

10

39

34

10

6

42

41

35

34

9

10

6

8

34

47

47

27

36

37

7

14

12

5

8

8

69

34

68

35

28

7

24

7

Table 3: Distribution of Attributes between Women and Men

Women (58%)

Men (42%)

Percentage of women and men with attribute

Race, Ancestry

Asian

18

23

Black

49

40

Hispanic

25

28

White

8

9

Age

Age: 18-30

27

28

Age:31-45

36

35

Age: 46-60

23

23

Age >60

14

14

Marital Status

Married or cohabiting

45

59

Separated, divorced, widowed

28

16

Never married

27

25

Resources (average score)

Income-to-needs-ratio: hhinc/poverty line

3.16

4.15

Years of Education

Education high

21

24

Education Medium

25

23

Education moderate

29

29

Education low

25

24

Employment status

Employed

61

73

Unemployed

9

7

Inactive

30

20

Immigration status

US born

60

54

Non-US born

40

45

US region

North East

24

21

Mid West

9

8

West

24

30

South

43

41

Health, Childhood, Society

Good physical health

77

82

Childhood traumas

46

55

Church membership

36

23

Disability Scores (average)

WHO-DAS: cognitive score

1.37

0.96

WHO-DAS: social interaction score

0.94

0.61

Notes to Table 3

1. Asian: Vietnamese, Filipino, Chinese, all other Asian; Hispanic: Puerto Rican, Mexican, all other Hispanic;

Black: African American, Afro-Caribbean.

2. Education high: 16 or more years of education; Education medium: 13-15 years; Education moderate:

12 years; Education low: 0-11 years

3. Childhood traumas: yes to any of the following: fidgety childhood; frequently in trouble with adults for 6

months or more during childhood or adolescence; lying, stealing as child or teenager; run away frequently,

played truant, or stayed out late as child or teenager; separation anxiety for 1 month or more as child.

4. WHO-DAS: World Health Organisation Disability Assessment Score: higher the score, greater the

disability.

22 .

Table 4

Marginal Probabilities from “sad, empty, depressed” Logistic Equation

Entire Sample

Female Sample

Male Sample

(10,087)

(5,861)

(4,226)

Mg. prb

Z val

Mg. prb

Z val

Mg. prb

Z val

Sex

Male

Race, Ancestry (residual: White)

Asian

Black

Hispanic

Age (residual >60 years)

Age: 18-30

Age:31-45

Age: 46-60

Marital Status (residual: never married)

Married or cohabiting

Separated, divorced, widowed

Resources

Income-to-needs-ratio: hhinc/poverty line

Years of Education (residual, low education)

Education high

Education Medium

Education moderate

Employment status (residual: inactive)

Employed

Unemployed

Immigration status (residual: born abroad)

US born

US region (residual: South)

North East

Mid West

West

Health, Childhood, Society

Good physical health

Childhood traumas

Church membership

Disability Scores

WHO-DAS: cognitive score

WHO-DAS: social interaction score

-0.097

-8.98

-0.142

-0.122

-0.025

-5.8

-6.27

-1.08

-0.127

-0.088

0.014

-3.6

-3.29

0.43

-0.160

-0.161

-0.069

-4.93

-5.98

-2.2

0.083

0.089

0.095

3.72

4.38

4.6

0.079

0.073

0.083

2.73

2.75

3.13

0.092

0.113

0.111

2.63

3.57

3.42

-0.054

0.058

-3.81

3.32

-0.045

0.043

-2.37

1.97

-0.058

0.096

-2.72

3.24

0.002

1.35

0.001

0.6

0.003

1.25

0.087

0.035

0.022

4.81

2.16

1.45

0.083

0.031

0.022

3.48

1.43

1.12

0.087

0.037

0.020

3.23

1.49

0.88

-0.022

0.031

-1.5

1.39

0.005

0.050

0.26

1.78

-0.066

-0.003

-2.64

-0.09

0.001

0.1

0.013

0.74

-0.018

-0.91

0.017

0.011

-0.036

1.19

0.56

-2.13

0.017

-0.006

-0.024

0.89

-0.22

-1.04

0.017

0.038

-0.041

0.79

1.21

-1.76

-0.133

0.231

-0.026

-9.31

21.9

-1.81

-0.140

0.225

-0.039

-7.72

15.94

-2.07

-0.118

0.230

-0.002

-5.18

15.13

-0.1

0.013

0.011

7.7

5.16

0.015

0.012

6.51

4.12

0.009

0.010

4.15

3.04

Notes to Table 4

1. Depression is defined as answering yes to the following question: Have you ever in your life had a period,

lasting several days or longer, when most of the day you felt sad, empty, or depressed?

2. Asian: Vietnamese, Filipino, Chinese, all other Asian; Hispanic: Puerto Rican, Mexican, all other Hispanic;

Black: African American, Afro-Caribbean.

3. Education high: 16 or more years of education; Education medium: 13-15 years; Education moderate:

12 years; Education low: 0-11 years.

4. Childhood traumas: yes to any of the following: fidgety childhood; frequently in trouble with adults for 6

months or more during childhood or adolescence; lying, stealing as child or teenager; run away frequently,

platyed truant, or stayed out late as child or teenager; separation anxiety for 1 month or more as child.

5. WHO-DAS: World Health Organisation Disability Assessment Score: higher the score, greater the disability.

23 .

6. The rows of the table with typeface in italics are those variables for which the difference between the female

and male marginal probabilities was significantly different from zero at the 20% (or less) level of significance.

24 .

Table 5

Marginal Probabilities from “very discouraged” Logistic Equation

Entire Sample

Female Sample

(10,087)

(5,861)

Mg. prb

Z val

Mg. prb

Z val

Male Sample

(4,226)

Mg. prb

Z val

Sex

Male

-0.072

-6.50

Race, Ancestry (residual: White)

Asian

-0.180

-7.55

-0.186

-5.54

-0.179

Black

-0.156

-7.92

-0.117

-4.33

-0.197

Hispanic

-0.096

-4.30

-0.068

-2.17

-0.129

Age (residual >60 years)

Age: 18-30

0.137

6.01

0.121

4.05

0.163

Age:31-45

0.129

6.20

0.118

4.36

0.146

Age: 46-60

0.122

5.77

0.127

4.65

0.117

Marital Status (residual: never married)

Married or cohabiting

-0.044

-3.09

-0.052

-2.69

-0.030

Separated, divorced, widowed

0.044

2.49

0.028

1.27

0.078

Resources

Income-to-needs-ratio: hhinc/poverty line

0.002

1.00

0.004

1.53

0.000

Years of Education (residual, low education)

Education high

0.096

5.25

0.089

3.66

0.102

Education Medium

0.060

3.61

0.066

3.02

0.047

Education moderate

0.031

2.04

0.037

1.81

0.023

Employment status (residual: inactive)

Employed

-0.015

-1.00

0.000

-0.02

-0.045

Unemployed

0.050

2.19

0.063

2.22

0.025

Immigration status (residual: born abroad)

US born

0.034

2.56

0.048

2.67

0.014

US region (residual: South)

North East

0.035

2.45

0.033

1.73

0.040

Mid West

0.035

1.74

0.041

1.56

0.027

West

-0.012

-0.68

0.008

0.36

-0.029

Health, Childhood, Society

Good physical health

-0.135

-9.32

-0.141

-7.66

-0.122

Childhood traumas

0.249

23.72

0.246

17.48

0.250

Church membership

-0.024

-1.62

-0.060

-3.15

0.030

Disability Scores

WHO-DAS: cognitive score

0.017

8.84

0.019

7.22

0.015

WHO-DAS: social interaction score

0.010

4.51

0.011

3.7

0.009

Notes to Table 5

Depression is defined as answering yes to the following question: Have you ever in your life

had a period, lasting several days or longer, when most of the day you were very discouraged

about how things were going in your life?

25 .

-5.37

-7.15

-4.14

4.52

4.46

3.52

-1.4

2.61

-0.06

3.7

1.86

0.99

-1.76

0.68

0.71

1.81

0.85

-1.19

-5.21

16.24

1.32

5.16

2.52

Table 6

Marginal Probabilities from “loss of interest” Logistic Equation

Entire Sample

Female Sample

(10,087)

(5,861)

Mg. prb

Z val

Mg. prb

Z val

Male Sample

(4,226)

Mg. prb

Z val

Sex

Male

-0.033

-3.24

Race, Ancestry (residual: White)

Asian

-0.111

-5.18

-0.140

-4.86

-0.088

Black

-0.092

-5.19

-0.081

-3.3

-0.105

Hispanic

-0.065

-3.33

-0.054

-1.97

-0.082

Age (residual >60 years)

Age: 18-30

0.176

7.55

0.159

5.16

0.207

Age:31-45

0.146

7.03

0.141

5.12

0.159

Age: 46-60

0.154

7.08

0.152

5.34

0.163

Marital Status (residual: never married)

Married or cohabiting

-0.040

-3.07

-0.041

-2.33

-0.031

Separated, divorced, widowed

0.054

3.26

0.034

1.65

0.097

Resources

Income-to-needs-ratio: hhinc/poverty line

0.003

1.69

0.005

2.22

0.000

Years of Education (residual, low education)

Education high

0.079

4.46

0.063

2.67

0.093

Education Medium

0.072

4.54

0.063

2.99

0.080

Education moderate

0.023

1.59

0.008

0.43

0.040

Employment status (residual: inactive)

Employed

-0.059

-4.26

-0.041

-2.32

-0.091

Unemployed

0.007

0.34

0.000

-0.01

0.018

Immigration status (residual: born abroad)

US born

0.031

2.55

0.053

3.18

0.001

US region (residual: South)

North East

0.043

3.16

0.050

2.76

0.032

Mid West

0.039

2.06

0.021

0.85

0.069

West

-0.010

-0.64

0.001

0.04

-0.015

Health, Childhood, Society

Good physical health

-0.124

-8.81

-0.133

-7.33

-0.110

Childhood traumas

0.224

22.56

0.212

15.56

0.237

Church membership

-0.014

-1.04

-0.038

-2.19

0.024

Disability Scores

WHO-DAS: cognitive score

0.016

10.03

0.016

7.86

0.016

WHO-DAS: social interaction score

0.010

5.27

0.013

5.05

0.004

Notes to Table 6

Depression is defined as answering yes to the following question: Have you ever in your life

had a period, lasting several days or longer, when you lost interest in most things you usually

enjoy like work, hobbies, and personal relationships?

26 .

-2.80

-4.20

-2.99

5.64

4.91

4.75

-1.56

3.37

0.12

3.51

3.27

1.83

-3.79

0.54

0.06

1.59

2.26

-0.66

-4.92

16.74

1.16

6.20

1.80

Table 7

Marginal Probabilities from the “Mild Anxiety” Logistic Equation

Entire Sample

Female Sample

(10,087)

(5,861)

Mg. prb

Z val

Mg. prb

Z val

Male Sample

(4,226)

Mg. prb

Z val

Sex

Male

-0.089

-8.58

Race, Ancestry (residual: White)

Asian

-0.110

-4.70

-0.124

-3.78

-0.107

Black

-0.101

-5.44

-0.092

-3.6

-0.110

Hispanic

-0.016

-0.74

0.012

0.38

-0.053

Age (residual >60 years)

Age: 18-30

0.011

0.53

-0.017

-0.63

0.059

Age:31-45

0.033

1.70

0.035

1.36

0.036

Age: 46-60

0.056

2.86

0.048

1.86

0.071

Marital Status (residual: never married)

Married or cohabiting

-0.017

-1.27

-0.019

-1.02

-0.007

Separated, divorced, widowed

0.004

0.22

0.009

0.45

-0.011

Resources

Income-to-needs-ratio: hhinc/poverty line

0.001

0.80

0.001

0.54

0.001

Years of Education (residual, low education)

Education high

0.094

5.32

0.079

3.37

0.113

Education Medium

0.059

3.68

0.038

1.79

0.088

Education moderate

0.050

3.39

0.044

2.27

0.055

Employment status (residual: inactive)

Employed

-0.015

-1.10

-0.005

-0.28

-0.032

Unemployed

0.006

0.27

0.004

0.14

0.007

Immigration status (residual: born abroad)

US born

0.023

1.78

0.031

1.8

0.004

US region (residual: South)

North East

0.071

5.12

0.051

2.78

0.100

Mid West

0.044

2.25

0.023

0.9

0.078

West

0.025

1.50

0.031

1.36

0.025

Health, Childhood, Society

Good physical health

-0.086

-6.24

-0.050

-2.82

-0.141

Childhood traumas

0.198

19.31

0.188

13.42

0.210

Church membership

-0.005

-0.37

-0.009

-0.47

-0.005

Disability Scores

WHO-DAS: cognitive score

0.011

8.40

0.017

8.04

0.005

WHO-DAS: social interaction score

0.006

3.74

0.006

2.82

0.005

Notes to Table 7

Mild anxiety is defined as answering yes to the following question: Have you ever in your life

had an attack of fear or panic when all of a sudden you felt very frightened, anxious, or

uneasy?

27 .

-3.34

-4.2

-1.79

1.79

1.23

2.34

-0.36

-0.41

0.58

4.25

3.57

2.45

-1.37

0.22

0.21

4.62

2.51

1.06

-6.29

14.36

-0.21

3.03

2.48

Table 8

Marginal Probabilities from the “Severe Anxiety” Logistic Equation

Entire Sample

Female Sample

Male Sample

(10,087)

(5,861)

(4,226)

Mg. prb

Z val

Mg. prb

Z val

Mg. prb

Z val

Sex

Male

-0.010

-1.66

Race, Ancestry (residual: White)

Asian

-0.020

-1.54

-0.030

-1.65

-0.007

Black

-0.012

-1.19

-0.007

-0.45

-0.015

Hispanic

-0.010

-0.90

-0.014

-0.84

-0.004

Age (residual >60 years)

Age: 18-30

-0.020

-1.94

-0.003

-0.15

-0.034

Age:31-45

-0.022

-2.28

-0.014

-0.97

-0.027

Age: 46-60

-0.014

-1.60

0.002

0.13

-0.027

Marital Status (residual: never married)

Married or cohabiting

0.013

1.55

0.020

1.67

0.002

Separated, divorced, widowed

0.018

1.60

0.025

1.62

0.006

Resources

Income-to-needs-ratio: hhinc/poverty line

0.000

0.44

0.000

-0.16

0.001

Years of Education (residual, low education)

Education high

-0.010

-1.00

0.002

0.14

-0.023

Education Medium

0.005

0.61

0.010

0.73

-0.002

Education moderate

-0.006

-0.73

0.004

0.32

-0.017

Employment status (residual: inactive)

Employed

-0.011

-1.27

-0.004

-0.33

-0.020

Unemployed

0.010

0.74

0.016

0.87

0.001

Immigration status (residual: born abroad)

US born

0.026

3.42

0.019

1.74

0.031

US region (residual: South)

North East

0.013

1.47

0.011

0.87

0.014

Mid West

0.009

0.78

0.007

0.46

0.009

West

-0.005

-0.53

-0.005

-0.35

0.000

Health, Childhood, Society

Good physical health

-0.048

-4.76

-0.055

-3.98

-0.037

Childhood traumas

0.059

8.13

0.052

4.97

0.063

Church membership

-0.009

-1.21

-0.015

-1.44

0.000

Disability Scores

WHO-DAS: cognitive score

0.002

2.74

0.002

1.55

0.002

WHO-DAS: social interaction score

0.001

1.78

0.004

3.96

-0.003

Notes to Table 8

Severe anxiety is defined as answering yes to the following question: Have you ever had an

attack when all of a sudden you became very uncomfortable: you either became short of breath, dizzy,

nauseous, or your heart pounded, or you thought that you might lose control, die, or go crazy?

28 .

-0.41

-1.12

-0.28

-2.92

-2.23

-2.6

0.22

0.43

0.92

-2.13

-0.18

-1.85

-1.55

0.05

3.08

1.12

0.55

0.01

-2.68

6.59

0.04

3.37

-2.00

Table 9

The Decomposition of the Proportions of Men and Women who have experienced

Depression and Anxiety: all coefficients

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Sad, empty,

0.4420.442–

0.4430.3640.4420.006

0.443depressed

0.353 =

0.443 =

0.353

0.353

0.364

0.360

0.089

-0.001

=0.09

=0.011

=0.078

=0.083

Discouraged

0.4390.4390.4420.3850.4390.005

0.4400.375

0.442 =

0.375

0.375

0.385

0.381

=0.064

-0.003

=0.067

=0.010

=0.054

=0.059

Loss of

0.3320.3320.3260.3100.3320.012

0.330interest

0.293

0.326 =

0.293

0.293

0.310

0.303

=0.039

0.006

=0.033

=0.017

=0.022

=0.027

Mild anxiety

0.3990.3990.4040.3150.399-0.013

0.4010.322

0.404 =

0.322

0.322 =

0.315

0.318

=0.077

-0.005

=0.082

-0.007

=0.084

=0.09

Severe

0.1030.1030.0970.0850.1030.004

0.100anxiety

0.083

0.097

0.083

0.083

0.085

0.084

=0.020

=0.006

=0.014

=0.002

=0.018

=0.016

Notes to Table 9:

Column 1: Observed difference. Difference between the proportions of women and men,

who have experienced the condition, P( X , βˆ ) P( X , βˆ )

W

W

M

M

Column 2: Attribute Difference. Difference between the proportion of women who have

experienced the condition and the proportion of men who would have experienced the

condition if male attributes had been evaluated using female coefficients,

P( XW , βˆ W ) P( XM , βˆ W ) .

Column 3: Coefficient difference. Difference between columns 1 and 2 (Residual),

{ P( X , βˆ ) P( X , βˆ ) }-{ P( X , βˆ ) P( X , βˆ ) }= P( X , βˆ ) P( X ,βˆ

W

W

M

M

W

W

M

W

M

W

M

M

).

Column 4: Attribute Difference. Difference between the proportion of women who would

have experienced the condition if female attributes had been evaluated using male

coefficients and the proportion of men who have experienced the

condition, P( X , βˆ ) P( X ,βˆ ) .

W

M

M

M

Column 5: Coefficient difference. Difference between columns 1 and 4 (Residual),

{ P( X , βˆ ) P( X , βˆ ) }-{ P( X , βˆ ) P( X ,βˆ ) }= P( X , βˆ ) P( X , βˆ

W

W

M

M

W

M

M

M

W

W

W

M

).

XW and XM are the attribute vectors, and W and M are the coefficient vectors, for women and

men, respectively.

Column 6: Attribute difference obtained as the weighted average of columns 2 and 4, the

weights being the proportions of men (column 2) and women (column 4) in the sample.

Column 7: Coefficient difference obtained as the difference between men and women in their

“synthetic” probabilities of experiencing that condition.

29 .

Technical Appendix

The Decomposition of Probabilities

More formally, there are N people (indexed, i=1…N) of whom NM are men and NW

are women: k=M (men), W (women.). Define the variable Yi such that Yi=1, if the

person has had a condition (depression, anxiety), Yi=0, otherwise. Then, under a logit

model, the likelihood of a man or woman having had the condition is:

Pr(Yi 1)

exp( Xik β k )

F ( Xik βˆ k ), k M , W

k k

1 exp( Xi β )

(1)

where: X ik X ij , j 1...J represents the vector of observations, for person i of group

k, on J variables which determine the likelihood of the person having that condition,

and βˆ k jk , j 1...J is the associated vector of coefficient estimates for persons

from group k.

The average probability of a man or woman having had the condition is:

Nk

Y k P (Xik ,βˆ k ) N k 1 F ( Xik βˆ k ) k M ,W

(2)

i 1

So that:

Y W Y M [ P(XiM ,βˆ W ) P(XiM ,βˆ M )] [ P(XWi ,βˆ W ) P(XiM ,βˆ W )]

(3)

Alternatively:

Y W Y M [ P(XWi ,βˆ W ) P(XWi ,βˆ M )] [ P(XWi ,βˆ M ) P(XiM ,βˆ M )]

(4)

The first term in square brackets, in equations (3) and (4), represents the

“response effect”: it is the difference in average rates (of having had a condition)

between women and men resulting from inter-gender differences in responses (as

exemplified by differences in the coefficient vectors) to a given vector of attribute

values.16 The second term in square brackets in equations (3) and (4) represents the

16

That is, from applying different coefficient vectors to a given vector of attributes

30 .

“attributes effect”: it is the difference in average rates (of having had a condition)

between women and men resulting from inter-gender differences in attributes, when

these attributes are evaluated using a common coefficient vector.

So for example, in equation (3), the difference in sample means is decomposed

by asking what the average rates for men would have been, had they been treated as

women; in equation (4), it is decomposed by asking what the average rate for women

would have been, had they been treated as men. In other words, the common

coefficient vector used in computing the attribute effect is, for equation (3), the

female vector and, for equation (4), the male vector.

31 .