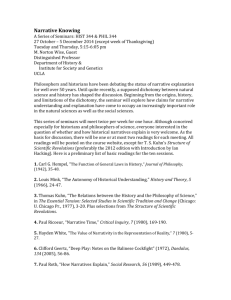

INTRO to shemot - The Foundation for Jewish Studies

advertisement

Introduction 1 Zornberg Introduction "Some books cannot be taken by direct assault; they must be taken like Jericho" (Ortega). Since these essays on Exodus are largely concerned with the interpretation of the narrative as it is found in midrashic sources, I would like to introduce them by offering a working definition of "midrash" and --- perhaps more to the point --- a personal meditation on the midrashic model for reading texts. My working definition --- with all due caveats, acknowledging the essentially undefined nature of the term1 --- would be this: Midrash, derived from the root darash, "to seek out" or "to inquire," is a term used in rabbinic literature for the interpretive study of the Bible. The word is used in two related senses: first, to refer to the results of that interpretive exegesis; and, second, to describe the literary compilations in which the original interpretations, many of them first delivered and transmitted orally, were eventually collected. These essays on Exodus make extensive use of some of these midrashic 1 See Gary Porten, "Defining Midrash," in The Study of Ancient Judaism, ed. J. Neusner (New York, 1981), 59-60. Zornberg Introduction 2 collections, notably Midrash Rabbah and Midrash Tanchuma. In addition, Rashi, the great French eleventh century commentator on the Torah, includes in his text a significant selection of midrashic interpretations; often, I refer to Rashi’s versions, where they offer interesting nuances on the original sources. Since Rashi’s commentary has been absorbed into the bloodstream of Jewish culture, his midrashic material has become a kind of "second nature" in the traditional reading of the biblical text. Before turning to a more personal view of the nature of midrashic reading, some technical observations are in order. These essays are based on the literary and liturgical device of "Parshat ha-Shavua," or "the Parsha": the Bible is read in Synagogue in weekly sections, so as to be completed in yearly cycles. Each Parsha is titled after a significant opening word. This device constitutes a way of living Jewish time; each week is saturated, as it were, with the material of that particular biblical section. One thinks, one studies, one lives the Parsha. If one is a teacher, this process is intensified. It is as a result of years of teaching the Bible in this form that I have come to articulate the ideas in this book. Since on one level, then, this book began life as oral presentations, delivered to a wide range of students, of all ages, backgrounds, and intellectual habits, these essays remain separate attempts to engage with a particular literary unit, the Parsha of the particular week. They address themes that arise compellingly from the Torah text, often from the midrashic or other interpretations of the text. On another level, however, they flow into one Zornberg Introduction 3 another, engaging with the narrative of the Exodus as a whole, and addressing the themes of the grand narrative: redemption, revelation, betrayal, and the quest for "God in our midst." In my approach, the biblical text is not allowed to stand alone, but has its boundaries blurred by later commentaries and by a persistent intertextuality that makes it impossible to imagine that meaning is somehow transparently present in the isolated text. Such an approach represents perhaps the greatest difficulty for the modern reader. It continues, in a sense, the rabbinic mode of reading, where "the rabbis imagined themselves a part of the whole, participating in Torah rather than operating on it at an analytic distance . . . [I]t follows that the words of interpretation cannot be isolated in any rigorously analytical way from the words of Torah itself."2 Elliot Wolfson articulates this reading practice: "the base text of revelation is thought to comprise within itself layers of interpretation, and the works of interpretation on the biblical canon are considered revelatory in nature."3 The blurring of boundaries between revelation and interpretation, between the written and the oral Torah, is a fundamental mode of the rabbinic 2 Gerald Bruns, Hermeneutics Ancient and Modern (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 115. 3 Elliot R. Wolfson, Through a Speculum that Shines. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994), 328. Introduction 4 Zornberg imagination. In this book, I have adopted this mode. I confess to a perhaps naive sense of the naturalness of this mode. However, as I invite the reader to enter the world of midrashic reading, I would like to offer an account of my reading practice, of how I understand the midrashic enterprise. ***************** Central to this enterprise is the telling of stories that fill in gaps in the written biblical text. For instance, the midrash that, in a sense, engenders this book --- about women’s play with mirrors and the "secret of redemption"4 --intends to explain a mysterious verse at the end of Exodus: "He made the laver of copper and its stand of copper, from the mirrors of the women who thronged, who came in throngs to the entrance of the Tent of Meeting" (38:8). The reader is baffled: Which mirrors (the mirrors)? What is the purpose of this specific gift to the Mishkan (Tabernacle)? Why is the expression tzava --- to throng, to proliferate --- repeated? Why is this particular copper contribution singled out from the larger mass of copper donated to the Mishkan? The midrash offers a narrative and, consequently, an interpretation of the enigmatic text: The women created the hosts, the throngs of Israel by their play with mirrors. As the midrash puts it: "It was all done with mirrors!" Such a narrative spins away from the biblical text; in a sense, it seems 4 See Chapter 1, pp.*********** Zornberg Introduction 5 unrooted, fantastic. Yet close study of the midrash reveals multiple skeins of connection, a network of textual roots within the language of the Bible. And --perhaps more importantly --- the midrash offers an answer to a repressed question: How are this people to be redeemable? Can they be imagined as, in some sense, generating their own freedom? If we make use of the classic image of birth, must we have recourse to a forced birth, a forceps delivery, in imagining the relations of God the "midwife" and the newborn?5 Or is there some way of catching the elusive moment of inner transformation that creates human possibility where before there was only necessity? The "secret of redemption," as the Rabbis call it, is the real problem at the heart of this midrash. While the question of "redeemability" is repressed in the biblical text, it is articulated in many midrashic sources, and it emerges significantly in Rashi’s commentary. Here, I would like to claim that this articulation of the repressed is the genius of midrashic narrative. If I adopt the psychoanalytic model, I suggest that the peshat, or plain meaning of the text , functions as the conscious layer of meaning; while the midrashic stories and exegeses intimate unconscious layers, encrypted traces of more complex meaning. The public, overt, triumphal narrative of redemption is therefore diffracted in the midrashic texts into multiple, contradictory, unofficial narratives which, like the unconscious, undercut, destabilize the public narrative. 5 See Yalkut Shimoni, 828. Zornberg Introduction 6 The result is a plethora of possible stories of redemption. Some of these will be attributed to "the enemy": they are false, adversarial narratives, Egyptian narratives, narratives of obtuse misunderstanding. These counter-narratives, the demonized expression of unthinkable thoughts, construct the official Israelite history of the Exodus as incomplete, inflated, or mythic invention. In Chapter 3, I discuss the problem of such counter-narratives and the implications of the Rabbis’ willingness to articulate them. Most significant, however, is the midrashic hospitality to the very concept of multiple alternative narratives. Time and time again, the magisterial biblical history of the Exodus is fractured in these midrashic versions. Moreover, the biblical text itself seems to give warrant for such retellings. Several times, the Torah itself emphasizes the importance of telling the story to one’s children and grandchildren. At certain moments, this imperative to narrate Exodus becomes the very purpose of the historical event: it happened so that you may tell it. At the heart of the liberation account, indeed, God prepares Moses with a story to tell a future child; this rhetorical narrative, astonishingly, precedes the historical narrative of liberation. One might perhaps assume that these stories of the future are standard retellings of the biblical narrative. Not so: the biblical text itself includes four versions of the narrative to respond to four hypothetical questioning sons of the Zornberg Introduction 7 future.6 These become typologies of four sons, who are later characterized in the Haggadah --- read each year on the night of Passover --- as the wise, the wicked, the simple, and the one who does not know how to ask. Even in the biblical sources, where the four passages are dispersed, the difference between the four versions is remarkable. In the Haggadah, this difference is presented as a psychological response to different types of child; but even the biblical text seems to offer an invitation to modulate the story to meet varying rhetorical ends. If the stories of the future are to be multiple, responsive to time and place and temperament, then the midrashic narratives exemplify this diffraction of the original narrative at its most radical. Essentially, I suggest, they raise both philosophical and psychological questions: about metaphysical truth and about the nature of the self. The notion that knowledge of reality is singular, absolute, static and eternal is tested in these midrashic narratives of the foundational events in Jewish history. The midrashic versions convey a plural, contextual, constructed and dynamic vision of reality. The "Platonic ideal" in the history of philosophy is describe by Isaiah Berlin: it posits . . . that all genuine questions must have one true answer and one only, all the rest being necessarily errors; in the second place, that there must 6 These dialogues are found in Exod 12:26--27; 13:8; 13:14; and Deut 6:20--21. Zornberg Introduction 8 be a dependable path towards the discovery of these truths; in the third place, that the true answers, when found, must necessarily be compatible with one another and form a single whole, for one truth cannot be incompatible with another --- that we knew a priori. This kind of omniscience was the solution of the cosmic jigsaw puzzle.7 As against this view, which obtained in Western philosophy till the late nineteenth century, the midrashic literature presents a heterogeneous, even --consciously and ambivalently --- a heretical multiplicity of answers.8 Exodus as a narrative that consistently deploys the "omnipotence effect," to use Meir Sternberg’s term, is significantly diffracted by the many counter-narratives that the midrash generates from within the triumphal and unequivocal master story. "What really happened in Egypt?" becomes a less important question than "How best to tell the story? Where to begin? What in the master story speaks to one and therefore makes one speak?" The psychological dimension of these counter-narratives is no less crucial. Diffracted narratives interrogate the nature of the self. The American psychoanalyst, Stephen Mitchell, describes one facet of the problem: People often experience themselves, at any given moment, as containing 7 Isaiah Berlin, The Crooked Timber of Humanity (New York: Knopf, 1991), 5-6. 8 See Chapter Three, pp. ************* Zornberg Introduction 9 or being a "self" that is complete in the present; a "sense of self" often comes with a feeling of substantiality, presence, integrity, and fullness. Yet selves change and are transformed continually over time; no version of self is fully present at any instant, and a single life is composed of many selves. An experience of self takes place necessarily in a moment of time; it fills one’s psychic space, and other, alternative versions of self fade into the background. A river can be represented in a photograph, which fixes its flow and makes it possible for it to be viewed and grasped. Yet the movement of the river, in its larger course, cannot be grasped in a moment. Rivers and selves, like music and narrative, take time to happen in.9 The "self" that was liberated from Egypt --- whether we consider the people as a psychological unit, or imagine an individual participant in the Exodus --experienced a limited, fragmentary version of events and a provisional sense of his or her own self. It is precisely through narration, by fulfilling the biblical imperative to tell the story, by the continuing interaction between parents and children, that transformed versions of self and of the meanings of liberation will be generated. In The Magic Mountain, Thomas Mann discusses the use of narrative to 9 Stephen Mitchell, Hope and Dread in Psychoanalysis. (New York: Basic Books, 1993), 102. Zornberg Introduction 10 experience the self in time: [T]ime is the medium of narration, as it is the medium of life. Both are inextricably bound up with it, as inextricably as are bodies in space. Similarly, time is the medium of music; music divides, measures, articulates time . . . Thus music and narration are alike, in that they can only present themselves as a flowing, as a succession in time, as one thing after another; and both differ from the plastic arts, which are complete in the present, and unrelated to them save as all bodies are, whereas narration --- like music --- even if it should try to be completely present at any given moment, would need time to do it in.10 Narrative needs time to do its work, to renegotiate the sense of total presence and fullness that the self craves. This, I suggest, is the core tension that the midrashic narratives express. By intimating unconscious conflicts about living in time, about the self as multiple, diffracted, discontinuous, the midrash often confronts the apparent simplicity of the biblical narrative with a more complex and nuanced notion of the self. In the midrashic account of the Exodus, these conflicts come to a head in the narrative of the Golden Calf.11 Here, the dilemmas of temporality are figured in grotesque and yet inevitable form. Moses’ "lateness" in descending 10 Thomas Mann, The Magic Mountain. (New York: Knopf, 1991), 541. 11 See Chapter Nine. Zornberg Introduction 11 the mountain precipitates a panic response whose shock waves spread wide and deep. In the midrashic versions, and in commentaries profoundly influenced by these versions, all the certainties of liberation, on the psychological as well as the historical and philosophical planes, are destabilized. Possible demonic narratives are released that will shape the nightmares of the future. The people experience the whips and scorns of time; the melancholy of those who do not know, in Julia Kristeva’s expression, "how to lose"; the insecurity of those who require certainty and yearn for total presence, who are, as one nineteenth century chasidic thinker has it, impatient with that need for prayer that is the posture of those who live within the veils of time.12 For the midrash to read in the biblical text such intimations of the unconscious life of a people becomes legitimate, in view of one necessary assumption of the Rabbinic mind: the implied author of the Torah is God. As Daniel Boyarin succinctly puts it: "This is not a theological or dogmatic claim but a semiotic one . . . If God is the implied author of the Bible, then the gaps, repetitions, contradictions, and heterogeneity of the biblical text must be read . . . "13 The midrashic search for multiple levels of meaning, the attempt to retrieve unconscious layers of truth, is warranted by the assumption that, as God’s work, the Torah encompasses all. "Turn it, and turn it, for all is in it," 12 Mei HaShiloach I, 30a-b. 13 Daniel Boyarin, Intertextuality and the Reading of Midrash (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990), 40. Introduction 12 Zornberg says R. ,14 using the image of the plough turning the earth, breaking, transforming, reversing, subverting. Two thousand years later, such an image of excavation becomes the informing image in Freud’s project: to unearth the repressed life that is encrypted within the human experience. The psychoanalytic project, like the midrashic one, represents a dissatisfaction with surface meanings, and a confidence that rich if disturbing lodes seam the earth’s depths. The activity of the ploughman is not only legitimate but imperative: in this way, the interpreter responds to the claim of God’s text. ********************** At this juncture, I would like to discuss one specific example of the midrashic retrieval of unconscious traces from within the biblical narrative. By contrast with the Genesis sagas, the absence of women from the narrative of Exodus --- and indeed from all the later books of the Bible --- is quite striking. This is not, of course, a total absence. There is the opening sequence in which women figure prominently: Jochebed, Miriam, Pharaoh’s daughter, the midwives, Moses' wife, Zipporah. All are related to the theme of birth, all are dedicated to what Waclav Havel calls the "hidden sphere" that endangers the totalitarian structure: to the baby crying within the brick.15 Once this theme has been established within the biblical text, however, women essentially disappear. 14 Pirkei Avoth 5:26. 15 See Chapter One, pp. ********** Zornberg Introduction 13 Miriam makes a brief reappearance, singing and dancing at the Red Sea, and later, in Numbers 12, she is afflicted with leprosy for maligning her brother Moses. Aside from this, there is one significant biblical moment devoted to women: in Numbers (27:1--12), the daughters of Zelofhad successfully claim a share in their father’s inheritance. A minor reference to women places them among the "wise-of-heart" who weave cloth for the Mishkan (Exod 35:25--26). The omission of women from the narrative can, of course, be seen as simply that --- an omission, a lack of specific interest in the feminine, which is absorbed into the larger body of the "children of Israel." However, Rashi precedes the feminist movement by many centuries when, in an extraordinary midrashic comment, he excludes women from the most intense moments in the biblical drama: they simply did not participate in the major rebellions of the people in the wilderness. Rashi comments on the final census of the people before entering the Holy Land: ‘In this [census], no man survived from the original census of Moses and Aaron, when they had counted the Israelites in the wilderness of Sinai’ (Num 26:64): But the women were not subjected to the decree against the Spies, because they loved the Holy Land. The men said, ‘Let us appoint (nitna) a leader to return to Egypt’ (14:4); while the women said, ‘Appoint (t’na) for us a holding among our father’s brothers’ (27:4). That is why the story of Zelafhad’s daughters is narrated directly after this. Zornberg Introduction 14 Rashi’s point is simple but revolutionary in its implications. Taking "man" literally, he limits the destruction of a generation, in punishment for the sin of the Spies, to the males only. While all the men over twenty died in the course of the forty years’ wandering, the women survived --- because, unlike the men, they loved the Land of Israel. Rashi’s midrashic claim is provocative in the extreme. With barely a hint in the text to support him, he presents a startlingly asymetrical demographic image of the people who entered the Holy Land, with women in the large majority. His basis in the text is the expression "No man survived . . ." and the fact that the story of the daughters of Zelofhad, who were inspired by love of the Land, immediately follows: the sequence invites the reader to notice that these women and the rebels involved with the Spies use the same word (t’na/nitna) to opposite effect. The compelling implication of Rashi’s comment, however, is not the demographic one. Rather it is that the absence of women from the text does not necessarily mean that they are assimilated into the general "children of Israel," as the plain meaning (peshat) of the text might indicate. Women have a separate, hidden history, which is not conveyed on the surface of the text. This history is a faithful, loving, and vital one, which excludes them from the dramas of sin and punishment that constitute the narrative of the wilderness. Indeed, Rashi’s midrashic source includes both the major crises in the wilderness as dramas in which women were not incriminated: Zornberg Introduction 15 In that generation, women would repair what men tore down. For you find that when Aaron said, ‘Break off your golden earrings [to make the Golden Calf],’ the women refused and protested, as it is said, ‘The whole people broke off the golden rings from their ears’ (Exodus 32:3). The women did not participate in the making of the Golden Calf. Similarly, when the Spies slandered [the Holy Land], and the people complained, God issued His decree against them for saying, ‘We cannot go up against the people . . .’ (Num 13:31). But the women werer not part of that movement, as it is written, ‘No man of them survived . . .’ --no man, not no woman, since it was the men who refused to enter the Holy Land, while the women approached Moses to ask for an inheritance (27:1).16 Women emerge as exemplary in this midrash: they repair what men have torn down, they reaffirm the value of love of the Holy Land and loyalty to the one God that men, in the rebellions of the Spies and of the Golden Calf, have eroded. This admirable history of women, however, is found only in the midrashic texts. Within the biblical narrative, it is barely intimated. The implication of this is profoundly paradoxical. In the written text, the absence of women would seem to imply that they are included in the large dramas of the Israelites in the wilderness; it is precisely in the midrash that women figure as having a separate, hidden history. In effect, the midrash makes the reader aware 16 Tanchuma Pinchas, 7. Introduction 16 Zornberg of a mistaken reading: all along, women have been really absent, really elsewhere. An alternative history, the midrashic history of women, would take us, at least at the most significant moments in the narrative, beyond the margins of the biblical account. Women’s story can be seen, then, at least at certain critical junctures, as the repressed narrative of the biblical text. Midrash retains the traces of that narrative and brings it to consciousness, with marked effects on the manifest level of meaning. All the midrashic narratives about women, indeed, can be registered in this way: the women’s mirror-play with their husbands in Egypt; the rich material on the experience of women at the Red Sea and on Miriam’s song/dance; Miriam’s well and its disappearance; and the strange emphasis on the female role in Korah’s rebellion.17 All construct a counter-reality to the one officially inscribed in the Torah; all deplore a complex ferment disguised by the lucidity of the text. Like the unconscious in the psychic economy, women remain a latent presence in their very absence; they represent the "hidden sphere" which must remain hidden if it is to do its work with full power, but which must be revealed in some form if that work is to be integrated. *********************** If women serve as the unconscious of the biblical story, the place where 17 I am grateful to Dina Kazhdan, Tali Stern, and Bracha Zornberg who pointed this out to me. Zornberg Introduction 17 they come to light is the midrashic narrative. We have suggested that midrash articulates the unconscious of the text: the hidden narratives, almost entirely camouflaged by the words of the Torah, emerge from the spaces, from the gaps in meaning, from the dream resonance of those words ("No man, not no woman . . .") This tradition of reading is intensively developed in a later period by the chasidic masters, who treat the midrashic texts as having, in their turn, emerged into conscious meaning, and who play with the latent meanings within and between those texts. Ultimately, conscious and unconscious layers of meaning inform one another; the written and oral Torah are not separated by an impermeable wall. The conscious level alone, the written text with its plain meaning, the undifferentiated history of the Israelite people in the wilderness, would provide a sterile version of the Exodus. It is the interplay of conscious and unconscious motifs that make for the grand narrative, which is capable of providing the matrix within which future narratives can take shape. The "particulars of rapture," in Wallace Stevens’s phrase, can evolve only where Two things of opposite natures seem to depend On one another, as a man depends On a woman, day on night, the imagined Introduction 18 Zornberg On the real. This is the origin of change. Winter and spring, cold copulars, embrace And forth the particulars of rapture come. Wallace Stevens, "Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction," iv. The grand narrative of the Exodus, then, must be a midrashic narrative in which the hidden, the repressed, can be at least partially witnessed. If the Exodus is to be a narrative for all times and all places, as Sefath Emeth, for example, claims,18 it must be capable of particular reincarnations through time. As in Roland Barthes’ famous example of those names of countries which cover the map in such large capitals that they become effectively invisible, the Exodus has come to constitute the very framework of Jewish perception and, for that very reason, is only partially visible. This metanarrative of the Exodus is the subject of a lyrical passage in R. Kook’s Olath Re’iya: The Exodus was such an event as only a crudely superficial eye could read as an event that happened and ended, and that has remained as a 18 See, e.g., Sefath Emeth, VaEra, 25. Zornberg Introduction 19 magnificent memory in the history of Israel and in the general history of mankind. But in reality, with a penetrating consciousness, we come to realize that the essential event of the Exodus is one that never ceases at all. The public and manifest revelation of God’s hand in world history is an explosion of the light of the divine soul which lives and acts throughout the world and which Israel, through its greatness and training in holiness, merits to disseminate powerfully through all the habitations of darkness to all generations. The essential work of the Exodus continues to have its effect; the divine seed which achieved Israel’s redemption from Egypt is still constantly active, in the process of becoming, without interruption or disturbance.19 All the life of the worlds, of individuals and nations, all power of generation and regeneration, can be read in the metahistory of the Exodus. For R. Kook, the first Chief Rabbi of the restored State of Israel, it is the organic connection between the "explosion" of particulars and the rapture of the Exodus that is accessible to the penetrating consciousness. The Exodus has no end and no limit. Such a view sets itself firmly against the historicizing consciousness, which Susan Sontag has characterized as the "predatory embrace" of the modern period, "the gesture whereby man indefatigably patronizes himself . . . More and more, the shrewdest thinkers and artists are precocious archaeologists of 19 R. Kook, Olath Re’iyah, 26--7. Introduction 20 Zornberg these ruins-in-the-making."20 From R. Kook’s perspective, the original liberation from Egypt participates in a continuum of sun-bursts: the history of man’s possibilities is not exhausted. Indeed, in the tradition of Chasidic thought from which he draws his inspiration, the original Exodus need not even be regarded as the overwhelming epic event that reduces all future experiences of liberation to pale replicas. Precisely the opposite dynamic may be true: the people who left Egypt were perhaps unfit for redemption, incapable of hearing God’s word in any real fullness. Their hopes in leaving the land of terror were shriveled by the cramped conditions of their nurture; they were cramped hopes, Egyptian-shaped hopes. Like the patient entering analysis, who can have only a distorted view of the process awaiting him, of the way in which it will expand the underlying structures of experience, the Israelites leave Egypt more like a man Flying from sonething that he dreads than one Who sought the thing he loved. ( William Wordsworth, "Tintern Abbey.") And like the analyst whose hopes for the patient are radically different from 20 Susan Sontag, ‘“Thinking Against Oneself”: Reflections on Cioran,’ in Styles of Radical Will (New York: Anchor Books, 1993), 74-5. Zornberg Introduction 21 those of the patient for himself, God begins a process with His people in a stage of arrested development, a process that will lead them into fuller, unimagined life. However, in this scenario, in which God’s hopes and the people’s hopes are profoundly different, there is a hidden assumption about the arrested "truer self" of Israel, the self that harks back to the foundational narratives of Genesis. Both analyst and patient share a hope for the unfolding of that truer self. But such a shared hope is at first almost invisible; only the discordance is visible. Intensely challenging passages in Chasidic literature tell of the development of that divine seed in history. Later narratives of the Exodus complete and compensate and restructure the inadequacies of the historical event as the people first lived it. Redemption is engendered by the changing stories of redemption that, with richer idiom, amplify the particulars of rapture. Sefath Emeth, for example, addresses the unconsummated experience of the historical Exodus.21 Telling the story of the Exodus is so imperative because of the chipazon, the panic haste, in which the original generation left Egypt. The existential quality of the historical Exodus, that is, reflected a rawness, an immaturity of spirit that later narratives, in some sense, will bring to ripeness.22 In this way, Sefath Emeth beautifully explains the people’s "deafness" to the 21 Sefath Emeth, Pesach, 72. 22 See Chapter Three, pp.************* Zornberg Introduction 22 possibility of redemption: "And they could not hear Moses for shortness of spirit and hard labour" (6:9). What they are unable or unwilling to hear is God’s promise couched in four synonyms for redemption ("I shall release . . . I shall save . . . I shall redeem . . . I shall take you to Me as a people . . ." [6:6-7]) --the classic arba leshonot geulah (four languages of redemption). "And therefore," writes Sefath Emeth, "we must now tell the story of the Exodus!" The paradox is compelling: out of the inadequacy of the historical event as it was registered by those who lived it is generated "Torah for all generations," each with its own language, its own existential framework for conceiving of redemption. Each generation thus has an exclusive opportunity to reorganize, reorder (seder --- order --- is the theme as well as the name of the Passover night) what originally was inchoate, disoriented. So "the story of redemption is constantly being revealed," as a fuller, more complex sense of self yields richer understandings of the master-narrative. The four languages of redemption, then, represent the infinite particular idioms that will inform the narratives of the future, which will continuously articulate aspects of what was only implicit in the original event. In the context of an uninterrupted interaction with the master narrative, the people will engender forms of testimony to God’s redemption that are not merely restatements of the known, but testings, trials of self and world that give birth to new structures of knowledge. Like the technique known as "remastering," in which precious original musical performances are liberated years later from the Zornberg Introduction 23 limitations and distortions of primitive recordings, the later languages of redemption seek to liberate an original divine impulse in an unprecedented manner.23 Such a concept of narrative cuts away the security of an ideal original narrative. Indeed, in a rather disconcerting sense, it dismantles the very platform that the original narrative uses to do its work: a privileged story of redemption replete with miracles, an inspired and infallible leader whose every word comes from God. The issue is not the objective truth of these ideas, but the people’s need to wean themselves of the infantile longings that have invested Moses with such powerful transferential significance. The power of the transferential fantasy helps to move the patient towards healing; but, at a more mature stage, the fantasy must be dissolved. The anguish of this paradox is the subject of Chapter Nine: in the light of a comment by Meshech Chochma,24 --- Talmudist and contemporary of Freud --- Moses’ "transferential" role becomes the latent theme of the Golden Calf episode. If fuller and richer languages for redemption are to evolve, fantasies that fetishize the past must be relinquished. The "particulars of rapture" can come 23 For a similar notion of transgenerational religious experience, in which the later experience completes and in a sense transcends the original, scriptural experience, see Sefath Emeth, Pesach, 55. 24 Meshech Chochma to 32:19. Zornberg Introduction 24 forth only when "Two things of opposite natures" interplay. This is where the midrashic mode is powerful. Here, past and present interact: the original text of Exodus and the narrative that will endow that matrix with generative force. Here is the mutual dependence --- "as a man depends On a woman" (Stevens); for without the black-on-white words of the scriptural narrative nothing can be generated, but without the evolving "languages," idioms of redemption, the foundational rapture recedes beyond recall. Or, more importantly: a strong written narrative endows the future with a structure of meaning; but it is the weakness, the gaps, the "unthought known" (Christopher Bollas’s expression) in that narrative that paradoxically invites the future to discover the primordial energy repressed in the text. As we have seen, it is the Israelites’ inability to appropriate their own redemption that makes redemption a matter of endless testimony. In this sense, I have suggested that there are two narratives of Exodus: the narrative of the day, and the narrative of the night (see Chapter Three). The daynarrative tells of the public, manifest, consciously perceived and transmitted liberation from Egypt; the night-narrative tells of chipazon, of panic haste, of unassimilated experience, as it tells also of God who "leaps" (pasach) --- a lurching, syncopated movement --- over houses, creating gaps for liberation. It is this second narrative that engenders questions and multiple, not always harmonious narratives. This narrative, too, is the domain of the unconscious, of midrashic counter-worlds that endow the manifest world of the biblical text Zornberg Introduction 25 with depth and vitality. The most potent image for the interaction of opposites that I am trying to convey remains the erotic one: " . . . as a man depends On a woman . . . This is the origin of change." It is for this reason, it seems to me, that the midrash is fascinated by that alternative world of the feminine, which must not be revealed, but which must be intimated. The mirrors in which women play with their husbands, "swinging them with words,"25 remain, for me, the most evocative symbol of redemption. Here is the mode of infinite possibility, of six hundred thousand babies at a birth --- and it is all done with mirrors. A river of coruscating souls, endlessly varied, shimmers forth from these mirrors: who can predict the force of these particulars of rapture? And yet, Moses’ voice, suspicious, fastidious, is retained as a counter-force in the midrash. The effect is of an almost unbearable tension: even as God chides Moses, supporting the women with their mirror play, the values of gezera, of what must be, of order and consciousness and control, are not totally neutralized. Freedom and law, possibility and necessity: these are the poles between which the electric current of redemption must run, if the particulars of rapture are to come forth. In terms of reading practice, this means a dialectical tension between peshat (plain meaning) and midrashic narrative. In philosophical or psychological terms, this means an awareness of the tension between "finitude 25 Rashi to 38:8. See Chapter One, pp. *********** Zornberg Introduction 26 and infinitude," to use Kierkegaard’s expression. The central issue for Kierkegaard, and for readers of Exodus, is freedom: "freedom is the dialectical aspect of the categories of possibility and necessity."26 Each mode has its own danger, its form of despair. On the one hand, there is "[t]he fantastic . . . which leads a person out into the infinite in such a way that it only leads him away from himself;"27 in its relation to God, as well, "this infinitizing can so sweep a man off his feet that his state is simply an intoxication. To exist before God may seem unendurable to a man because he cannot come back to himself, become himself."28 On the other hand, there is another kind of despair which "seems to permit itself to be tricked out of its self by 'the others'. . . such a person forgets himself, forgets his name divinely understood."29 This second despair, the despair of finitude, is entirely unregarded in the world: this is the pathology of the gezera modality, which is vindicated by all the prudential wisdom of the world: For example, we say that one regrets ten times for having spoken to once 26 Soren Kierkegaard, The Sickness unto Death, trans. by Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980), 30. 27 Ibid., 31. 28 Ibid., 32. 29 Ibid., 33-4. Zornberg Introduction 27 for having kept silent --- and why? Because the external fact of having spoken can involve one in difficulties, since it is an actuality. But to have kept silent! And yet this is the most dangerous of all . . . Not to venture is prudent. And yet, precisely by not venturing it is so terribly easy to lose what would be hard to lose, however much one lost by risking, and in any case never this way, so easily, so completely, as if it were nothing at all --- namely, oneself.30 Between silence and speech, silence is the more dangerous: its very safety endangers the self. Through such paradoxes, Kierkegaard conveys the difficulties of the dialectic: between finitude and infinitude, possibility and necessity, the human being struggles for an authentic freedom. This struggle, I suggest, lies at the very heart of the project of reading Exodus.31 Between the self that is and the self, or selves, that may be, the particulars of rapture are always being reborn. It is for this reason that the Exodus, and the Passover32 festival that celebrates it, focuses so compellingly on telling and retelling the story. It is only by taking the real risks of language, 30 Ibid., 34. 31 See Chapter Eight for a discussion of finitude and infinitude figured in the "bells and pomegranates" of Aaron’s priestly robe (*********) 32 Cf. the classic midrashic pun on Pesach - Peh sach ("the mouth speaks"). Zornberg Introduction 28 by rupturing the autistic safety of silence, that the self can reclaim itself. To venture into words, narratives, is to venture everything for the sake of that "self before God."33 And yet --- and here, the dialectic becomes most painful --- perhaps all the many words of the Exodus narrative, of the narratives of the future, specifically of the Seder night, all in a sense weave endless words around the inexpressible heart of the matter. As though by indirections to find direction out, we talk and we tell at such length because we cannot articulate what is essential. We cannot pluck out the heart of the mystery. Perhaps all the narratives in the book of Exodus are externalized versions of an intimate story more truly told in The Song of Songs. This, at least, is the midrashic view of the matter. The longing, the dynamics of desire: this is the subject of Exodus. So we speak and unpack our hearts with words, knowing that the essential longing is enthralled in silence. R. Hutner34 writes of this tension, of the repressed desire like an erotic longing that, inexpressible, erupts in displaced forms. These complex eruptions of language are the progeny of a great silence. Ludwig Wittgenstein said, "Whereof one cannot speak, one must be silent." 33 Sickness, 35. See Chapter Two for a discussion of speech as an expression of liberation from Egypt. 34 Pachad Yitzhak, Pesach, 77. It is interesting that it is women’s desire that serves as a model for this inexpressible spiritual energy. Zornberg Introduction 29 R. Hutner describes the Jewish practice of a kind of verbal catharsis that resembles the Freudian; his version might be, "Whereof one cannot speak, one must say everything." Commenting on the lechem oni, the bread of affliction (i.e. the matza) eaten on the Seder night, he bases his essay on the talmudic expansion: "bread to which one responds with many words" (a pun on oni [affliction] and onin [response]).35 These many words of the Seder night, of the continuing narratives of Exodus, represent an absence, an unattainable longing for full presence. The molten core of the self remains unreleased, unspeakable. Therefore, the cascade of language, ideas, images, which, by displacement, evoke a speechless passion. On Passover, the mouth speaks (peh sach): all the particulars of rapture intimate an absolute desire. R. Hutner’s account has a somber, almost tragic resonance. Ultimately, there is no expressing the heart of the matter. All the coruscations of possibility, all the midrashic versions of an original moment of liberation, all leave some core self still in prison, still in Egypt (Mitzrayim), still constrained in narrow places (meitzarim). All the mirrors of all the women cannot offer total liberation. And yet, even in R. Hutner’s somber account, there is the moment of surprise: language is the very means by which the imprisoned heart gains freedom. As in the psychoanalytic model, speaking of many things, one comes 35 B. Pesachim 36a. Zornberg Introduction 30 by indirection at the core. This generation of truth through language, the experience of speaking beyond one’s means, has an unwitting character. It happens in the interaction between two people: "one does not have to possess or own the truth in order to effectively bear witness to it."36 Language as testimony, then, can give access to the hidden passion; in a sense, the "many words" of the Exodus narratives beget that passion. This experience is, one might say, the very taste of freedom:37 the taste in the mouth that is impossible to communicate to those unfamiliar with it, and that makes one willing to become a medium of testimony. I think of midrash with its "many words" concealing/revealing a central mystery as offering a bridge between old hopes and the fullness of an unknown future identity. New narratives of redemption create the very freedom that the original protagonists could not "hear." The old hopes, as Wordsworth intimates, are born from dread. The midrashic mode offers a transformation of those old hopes and a new way of imagining the self. And the quest for such transformation continues to inform the reading practice and the spiritual hopes of those who enter this world of Exodus. This, at any rate, has been my quest in 36 Shoshana Felman, “Education and Crisis, Or the Vicissitudes of Teaching,” in Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis and History (Routledge, Kegan, Paul), 15. 37 See Mei HaShiloach ll, 13b. Zornberg Introduction 31 this book. I ask not to share the "secret of redemption" --- that is far beyond my reach; but to find those who will hear with me a particular idiom of redemption. And within the particulars of rapture to hear what cannot be expressed.