Truth-telling - Disclosure and Confidentiality

advertisement

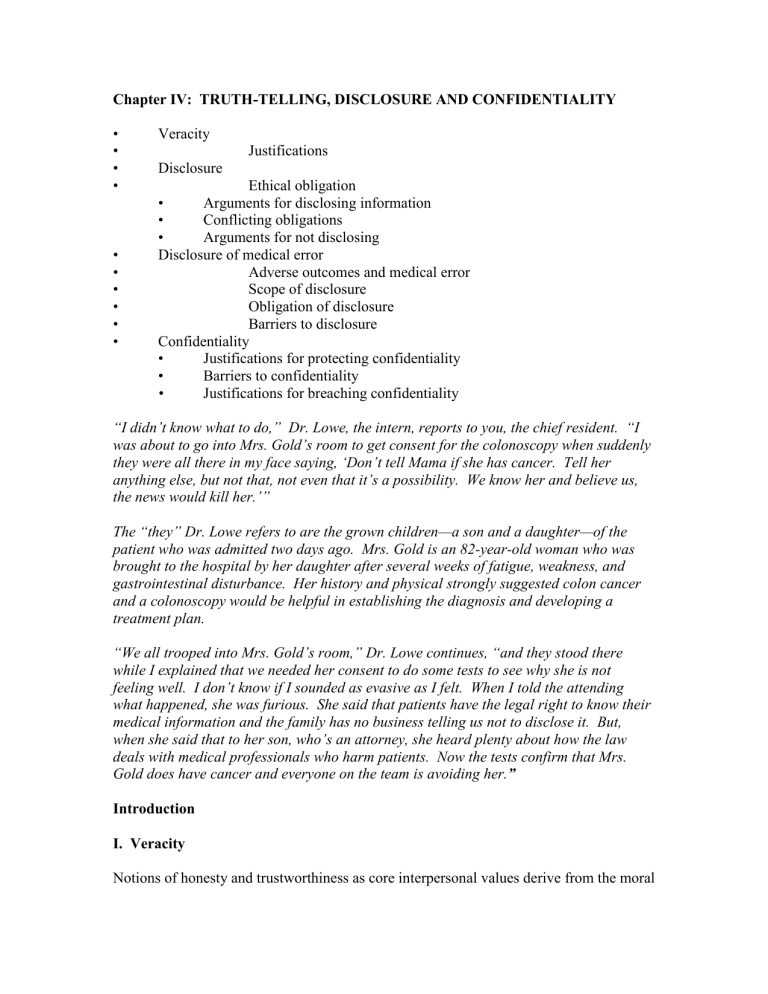

Chapter IV: TRUTH-TELLING, DISCLOSURE AND CONFIDENTIALITY • • • • • • • • • • Veracity Justifications Disclosure Ethical obligation • Arguments for disclosing information • Conflicting obligations • Arguments for not disclosing Disclosure of medical error Adverse outcomes and medical error Scope of disclosure Obligation of disclosure Barriers to disclosure Confidentiality • Justifications for protecting confidentiality • Barriers to confidentiality • Justifications for breaching confidentiality “I didn’t know what to do,” Dr. Lowe, the intern, reports to you, the chief resident. “I was about to go into Mrs. Gold’s room to get consent for the colonoscopy when suddenly they were all there in my face saying, ‘Don’t tell Mama if she has cancer. Tell her anything else, but not that, not even that it’s a possibility. We know her and believe us, the news would kill her.’” The “they” Dr. Lowe refers to are the grown children—a son and a daughter—of the patient who was admitted two days ago. Mrs. Gold is an 82-year-old woman who was brought to the hospital by her daughter after several weeks of fatigue, weakness, and gastrointestinal disturbance. Her history and physical strongly suggested colon cancer and a colonoscopy would be helpful in establishing the diagnosis and developing a treatment plan. “We all trooped into Mrs. Gold’s room,” Dr. Lowe continues, “and they stood there while I explained that we needed her consent to do some tests to see why she is not feeling well. I don’t know if I sounded as evasive as I felt. When I told the attending what happened, she was furious. She said that patients have the legal right to know their medical information and the family has no business telling us not to disclose it. But, when she said that to her son, who’s an attorney, she heard plenty about how the law deals with medical professionals who harm patients. Now the tests confirm that Mrs. Gold does have cancer and everyone on the team is avoiding her.” Introduction I. Veracity Notions of honesty and trustworthiness as core interpersonal values derive from the moral imperative of veracity. Three justifications that have been advanced to support the obligation of veracity have particular relevance to the therapeutic relationship. They are “respect owed to others . . . fidelity and promise-keeping . . . [and] fruitful interaction and cooperation.” (Beauchamp and Childress, 396-7) • Respect for others is reflected in the ethical principle of autonomy. The capable individual’s right to be self-determining imposes on physicians the obligation to provide adequate information for informed health care decision making and protecting the individual’s control over personal information. • Fidelity and the keeping of promises are central elements in the fiduciary relationship between patient and physician, creating an implicit contract that both parties will be honest and will honor their commitments. • Productive therapeutic interactions rely on the truthful management of information, including but not limited to protecting patient confidences and the security of medical records. The effective physician-patient relationship depends on the exchange of accurate and complete information about symptoms, diagnosis, prognosis and treatment options, as well as confidence that care plans will be followed and patient wishes will be honored. How information is elicited, protected and shared is central to the therapeutic relationship, often creating ethical dilemmas when professional obligations conflict. II. Disclosure A. Ethical obligation Collaborative decision making and informed consent are possible only in the context of reasonable disclosure of necessary or material information. Patients and their authorized surrogates are ethically and legally entitled to sufficient information to understand the likely course of the medical condition, evaluate the therapeutic options and make choices consistent with their goals and values. Disclosure invokes the ethical principles of respect for autonomy (the patient’s right to the information that promotes effective decision making), beneficence and nonmaleficence (the physician’s obligation to maximize benefits and minimize harms), and clearly illustrates the tension among the physician’s obligations. The benefits of disclosing information that enhances patient understanding and self-determination are weighed against the potential harms of anxiety and stress that disclosure may cause. The balance of power easily shifts to the physician, who controls the information and whose obligation is to create a more level ground for discussion and decision by providing what the patient needs to know. B. Arguments for disclosing information The arguments in favor of disclosure are both ethical and practical. Truth telling implicates notions of personhood and relatedness in fundamental ways. To know the truth about ones current and future condition is essential to a sense of self, especially as that condition changes and possibly deteriorates. Withholding information impairs decision making about care and other life plans. Even when treatment options are limited, knowing what to expect allows patients to prepare for what lies ahead. Truth telling also goes to the core of trust-based relationships, especially those among family members and between the patient and care providers. Shielding patients from the truth is generally an imperfect undertaking, requiring the collusion of others, including staff, family and friends, in a conspiracy of silence. Yet, patients—even children and adults with a history of not wanting to know—sense when things are being kept from them and may avoid discussion as a way of accommodating those protecting them. The burden of the deception itself thus can be a barrier to communication. Perhaps the most damaging result of withholding information is that the patient is isolated at precisely the time when close and supportive relationships are essential. In short, although the obligation of truth telling is not an absolute, it is something that requires a compelling reason to disregard. C. Conflicting obligations The tension arises when physicians feel that their obligations require them to either disclose information that the patient may not want or withhold potentially problematic information, all in the name of promoting the patient’s well-being. The challenge is trying to determine what the patient should know in order to receive the care she needs. Because the quality of treatment decision making is enhanced when patients are knowledgeable about their conditions and therapeutic options, consent that is legally and ethically valid requires the disclosure of relevant information. The difference between truth telling and truth dumping, however, is the distinction between providing specific information that is material to the individual’s situation and indiscriminately overloading the patient with facts in the interests of completeness. Patients often indicate what they want to know and perceptive clinicians can be guided by their spoken or unspoken signals. Truth dumping also occurs when physicians disclose information without providing explanations or guidance that frame the decisions patients or surrogates must make. The skill required for disclosure is the same as any other clinical skill—knowing when to act, what to do and how much to provide. Patients have both the right to receive information and the right not to receive it. Some people, especially those who are elderly, anxious, easily confused or from cultures that do not place a high premium on individual autonomy, find it burdensome and even frightening to learn about their conditions and be asked to make treatment decisions. For them, authentic autonomy is expressed in the capacitated request not to be informed and the delegation of decision-making authority to trusted others. But, as noted earlier, a waiver of consent is something that must be explicitly confirmed, not inferred. D. Arguments for not disclosing The more common disclosure dilemmas concern the withholding of information from patients who have not made that request, usually justified by professional obligations to protect patients and not inflict harm. Disclosure, especially of bad news, is one of the most difficult things physicians do and their evasion or awkwardness is often the result of efforts to avoid inflicting pain. Physicians often protect themselves and—they think— their patients by resorting to euphemism. “The patient has a grim prognosis” becomes “The patient is not doing well.” “The patient is dying” becomes “The patient is failing.” Rather than comfort, however, deliberate vagueness creates confusion, anxiety and unrealistic expectations. It is not uncommon for a family to react with frustration and seemingly unreasonable demands when told that, although their loved one is not doing well, aggressive treatments should be limited. The family argues that she could be doing better if only the physicians were doing more rather than less. Sometimes, discomfort in discussing bad news with the patient persuades physicians that disclosure would be harmful, when in fact it might only be distressing. Here the therapeutic privilege may be expanded beyond its strict definition (excuse from disclosure when the information itself would result in immediate, direct and significant harm to the patient) to situations in which the information would likely be upsetting, but not dangerous. Whenever physicians consider withholding information, especially from capacitated patients, they need to question who is being protected and whether the protection is truly warranted. Pressure also comes from families—either parents of young children or grown children of aging parents like the Gold family—not to share information with the patient. The reasons are usually “The news will kill her” or “You will take away all hope.” The first objection signals the need for reassurance that patients will not be burdened with information they cannot safely assimilate. The second objection speaks to realistic expectations. It is frequently necessary to redefine what can be hoped for—perhaps not long life or unlimited function, but rather increased comfort or a peaceful death surrounded by loved ones. When withholding information is suggested, the physician should start by determining the patient’s capacity, understanding of the clinical situation and desire for information. One approach is to say, “Mrs. Gold, the examinations and tests will be giving us information about your condition and then some treatment decisions will have to be made. Sometimes patients want to know all the informatin and sometimes they don’t. Who would you like us to talk to? Do you want us to discuss these things with you or with someone else?” Capable patients can then elect to participate in the process or voluntarily delegate that responsibility to another person. Even if Mrs. Gold explicitly says, “I don’t want to know and I want my son to make decisions for me,” she should be kept in the loop by being asked periodically, “Do you have any questions? Is there anything we can tell you?” A wish not to be burdened with information or decision making does not deprive patients of attention in other ways. III. Disclosure of Medical Error Mrs. Benning, a pregnant woman with diabetes, has been encouraged to undergo amniocentesis to determine the fetus’s lung development in order to plan induction of her delivery. Because there is a window of safety in delivering diabetics, this procedure is considered standard of care. During the amnio, the umbilical cord is nicked, resulting in bleeding and requiring an immediate caesarean section. The neonatology house staff requests an ethics consult to discuss whether the parents should be told the reason for the emergency delivery and, if so, whether the information should come from the obstetric team or the neonatologists. A. Adverse outcomes and medical error Adverse outcomes are unintended negative results of medical care that actually or potentially harm the patient. These untoward occurrences may be the result of carelessness or ineptitude, or they may reflect foreseen but unavoidable risk even when standard of care was practiced. The former—medical errors—are considered avoidable, while the latter are generally unavoidable, and distinguishing between them may be problematic, although quality of care is sometimes used as the standard. Other analyses distinguish between system and individual or human errors, attributing some adverse outcomes to problems in the delivery system and others to individual providers. This approach reflects the notion that “[n]o one person [is] responsible, because it is virtually impossible for one mistake to kill a patient in the highly mechanized and backstopped world of a modern hospital.” (Belkin, 28) It is only recently and gradually that the health care community has accepted the notion of a system-wide interlocking situation that either allows or prevents error. B. Scope of disclosure In the clinical setting, disclosure concerns information that would affect a patient’s understanding of and decision making about her medical condition and therapeutic options. The ability of a patient to make assessments and choices depends largely on the amount and quality of the information being considered. Because laboratory and examination findings are controlled by the care team, particularly the medical staff, disclosure of clinical information is at the discretion of the physician. Access to medical information is thus an inherently unequal process that places the patient at a distinct disadvantage in decision making and confers on doctors the obligation of disclosure. Disclosure includes but is not limited to the requirements of informed consent, which permit prospective analysis of benefits, burdens and risks of proposed interventions. Full disclosure promotes patient self-determination and protection, including retrospective analysis of unintended consequences. It has been suggested that, in addition to patients’ need for information to enhance decision making, there is also a desire just to understand what did or will happen to them. Taken together, the preview and review aspects of the disclosure obligation can be seen in the patient’s need to act and to know. C. Obligation of disclosure The basis of an obligation to disclose adverse outcomes rests on both ethical and legal foundations. 1. Disclosure as required by the fiduciary relationship The ethical principle of respect for persons requires that medical information be shared in order to foster patient autonomy, enhance trust, promote rational decision making and ensure active participation in treatment and care. Recognizing the need to ensure the provision of adequate information, courts have imposed fiduciary obligations of disclosure on physicians. Judicial reasoning is that these obligations exist when “one party is dependent on another for information or knowledge that only the first party possesses.” (Vogel and Delgado, 66-67) In the clinical setting, the physician is the person most likely to have and control information about an untoward event or medical error, heightening the professional obligation of disclosure. Indeed, this obligation is explicit in the American College of Physicians’ Ethics Manual, which holds that physicians should notify patients about medical errors “‘if such information significantly affects the care of the patient.’” (American College of Physicians. Ethics Manual, 3rd ed.) The patient who has suffered an undisclosed adverse event is thus doubly vulnerable— not only is she unaware of the actual or potential harms she faces and how to prevent or mitigate them, she may not know the nature of the event or even that it has occurred. Her reliance on the physician for information that will minimize harm and/or help her cope with the consequences creates an ethical imperative for timely and full disclosure of the adverse event. 2. Disclosure as an Extension of Informed Consent It is also possible to find the basis for a disclosure obligation in an expanded notion of informed consent, drawing on the concepts of mutuality, expectation and reliance. This analysis views informed consent as a compact entered into by physician and patient, the rules of which they both understand and to which they both agree. The doctor says, in effect, “Here is the information you need, including the possible risks.” The patient says, in effect, “I understand what you have said and I consent to the test or treatment, notwithstanding the potential harms, because I trust that you have told me everything I need to know in order to make a decision.” Implicit in the patient’s response is the following, “I trust that you will exercise all due care in treating me. I further trust that, if any of the foreseen but unintended harms should occur, you will disclose that information so that I can mitigate the negative consequences.” Seen in this light, informed consent takes on a retrospective as well as a prospective component. The patient is able to balance the benefits, burdens and risks in advance of treatment, and also mitigate potential harms and protect herself from further harms after an untoward event has occurred. Rather than a passive recipient of treatment, the patient becomes a fully equal partner in planning for and managing the outcomes of care. D. Barriers to Disclosure Despite the ethical justifications for disclosure and the acknowledged need to prevent or rectify harmful consequences of adverse events, physicians are very reluctant to discuss negative outcomes with patients and family. Reasons for avoiding disclosure include the difficulty of determining whether there was medical error, the belief that the information will only upset patients and family, and the omnipresent fear of legal action. Although liability to medical malpractice suits is invoked by physicians as the chief barrier to disclosure, it has been demonstrated repeatedly that instituting litigation is poorly correlated with the occurrence of adverse events, including negligence, and well correlated with how physicians handle discussions with patients about untoward outcomes, including disclosure of information about actual or potential harm. Additional concerns about who assumes the duty of disclosure and bears the responsibility are especially difficult in an academic medical center, which includes multiple levels of interdisciplinary staff and different authority structures. Perhaps even more threatening to physicians than the specter of malpractice litigation is the personal devaluation that accompanies acknowledging adverse events. This may include “a loss of personal confidence and self-esteem, diminished professional authority and reputation, as well as a loss of referrals and income.” (Bayliss, 338) The inability to cope with untoward outcomes appears to stem less from blatant callousness or dishonesty than from belief in the widespread myth of omniscience, infallibility, and total control that make up the perfect healer. This image, born in medical schools, nurtured throughout medical careers and sold to the public is shared by physicians and their patients, leading to unrealistic expectations, unreasonable disappointments and unbridgeable gaps in communication. IV. Confidentiality Mrs. C is a 32-year-old woman admitted to the MICU with bilateral pulmonary infiltrates and impending respiratory failure. Prior to intubation, she told her mother, the nurse and the social worker, “Don’t let them label me HIV+. I know they are thinking that and you can’t let them do it.” She had no history of past HIV testing and refused to address HIV as a possible diagnosis. Her hospital course has included treatment for genital herpes, PCP and cytomegaloviral pneumonia. She has required mechanical ventilatory support since admission. Mrs. C’s mother, Mrs. D, and 7 siblings have held a constant vigil during her 43-day hospitalization. Mrs. C’s children, ages 7 and 14, who appear to be in good health, visit often. Her husband of more than 5 years has been incarcerated for the past 6 months. Although the patient is being treated for AIDS-related complications, her family has not been directly confronted with her diagnosis because of her express wishes. Mrs. D, without asking the name of her daughter’s illness, acknowledges that her immune system has been compromised. She has agreed to the use of AIDS-related medications if you think they will be potentially beneficial to her daughter and, yesterday, consented to a DNR order. Mrs. C’s death appears imminent. Although you can no longer do anything to improve Mrs. C’s condition, you believe that the welfare of others is at stake. Do you have responsibilities to them? Can you meet your obligations to honor your patient’s confidence while protecting others from harm? Closely related to disclosure and central to the therapeutic relationship is the ethical obligation of confidentiality, which also derives from the moral imperative of veracity. “Confidentiality is present when one person discloses information to another, whether through words or an examination, and the person to whom the information is disclosed pledges not to divulge that information to a third party without the confider’s permission.” (Beauchamp & Childress, 420) In that sense, confidentiality, like truth telling, invokes the patient’s trust in and reliance on the physician’s integrity. A. Justifications for protecting confidentiality The notion that the therapeutic interaction creates a zone of privacy in which information is protected can be supported by the three justifications for veracity discussed earlier. • Respect for persons underlies patients’ control of who has access to their heath care information and requires that medical records be protected from unwarranted disclosure. The physician demonstrates respect for the patient by honoring the confidentiality of the therapeutic relationship. If personal information can be seen as a reflection of the most intimate aspects of the individual’s life, then control of that information can be seen as a form of self-determination. Protecting confidentiality also prevents the harms that result from unauthorized disclosure of sensitive information, such as HIV status and psychiatric histories. • • Fidelity and promise keeping are reflected in the bond of trust that requires the physician to hold in confidence information learned in the therapeutic interaction. This approach is based on the moral imperative to honor a duty or promise regardless of the results and holds that, absent explicit waiver by the patient, the professional is bound by the confidentiality inherent in the relationship and the understood privacy and trust promises. The argument also encompasses the notion of secrets, those pieces of our private selves we give in trust to others with the implicit or explicit understanding that they will be held in confidence. The effectiveness of the physician-patient relationship and the resulting quality of the health care depend on an atmosphere of trust that promotes the candid and complete exchange of information. This justification rests on the need to encourage patients to provide all relevant facts about their medical history and symptoms, no matter how private or potentially embarrassing, to facilitate accurate diagnosis and effective treatment. This consequentialist theory argues that, absent an obligation of strict nondisclosure, patients would avoid seeking treatment. B. Barriers to confidentiality Medical information is generated in the health care setting as a product of the therapeutic interaction between physician and patient; it is also generated in the pharmacy, the research lab, the autopsy room, the insurance office, the medical classroom and the hospital elevator. It goes into reports, books, lectures, legal briefs, and computers from which it is accessed by countless people for countless legitimate and not-so-legitimate reasons. The relationship between physician and patient is only one context in which medical confidentiality is raised. Once health care moved from the home to the institutional setting, once multiple subspecialties, legal and government bureaucracies, and third-party payors converged on each case, and once computers connected all of them, the number of people with legitimate and nonlegitimate access to medical information increased geometrically. In a 1982 article, a physician reported that medical information about his patient, whose case was not unusual or complex, was necessarily available to at least 75 people who provided direct or support health care services. (Siegler) The contemporary clinical setting has greatly enhanced the efficiency and efficacy of communication among care providers, while compromising the privacy of patients’ medical information. Concerns about the security of patient information prompted the inclusion of stringent regulations in the 1996 federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Consent to care with a loss of some measure of privacy is either explicitly obtained, through signed releases upon entering the hospital, or presumed, but the consent is never to be considered unlimited. For example, although it should be explained upon admission, it is generally understood that treatment in a teaching hospital includes having one’s records, examinations and therapies available for observation and study by students and house staff. Most patients expect that their cases will be discussed formally and even informally to obtain the benefit of other opinions and to provide teaching examples. They neither expect nor deserve to have their personal or medical information shared in public hospital areas or social situations. In addition to those who use medical information for treatment purposes, such data are routinely used by medical researchers, law enforcement agencies, attorneys (requesting their own clients’ records or those of other patients in connection with medical malpractice or personal injury), insurers (life, health, disability and liability), employers and creditors. Although these secondary users are generally required to access information though formal requests for patient record releases, they may not always follow procedure. Finally, there are potential users of medical information who have nothing to do with the patient’s health care, including those with commercial, political and media interests. C. Justifications for breaching confidentiality Based on well-established ethical and legal justifications, the longstanding obligation of confidentiality almost always precludes physicians from disclosing information learned in the course of the therapeutic interaction. Precisely because this ethical mandate is so central to the therapeutic relationship, exceptions are justified only when disclosure of confidential information is essential to preventing significant harm to other vulnerable individuals, especially those at unsuspected risk. In these instances, the patient’s right to confidentiality is considered to be outweighed by the obligation to protect those who are not in a position to protect themselves. The two following situations that justify breaching confidentiality illustrate the conflicting ethical obligations when competing claims are made for physicians’ fidelity. In both circumstances, the needs of the nonpatient(s) are elevated because their vulnerability is heightened by their very ignorance of the risks they face. • Providing information that prevents harm to an identified third party at risk (e.g., partner notification of exposure to HIV or sexually transmitted disease). This exception reflects the opinion in Tarasoff v. Regents of University of California, a 1976 case in which the court held that a psychotherapist who had prior knowledge of a patient’s intention to kill his unsuspecting girlfriend had a duty to warn her. Drawing on this reasoning, the New York State HIV/AIDS law was revised in 1998 to include partner notification, including the following elements: • Physicians are required to report to the state the names of patients newly diagnosed with HIV or AIDS. • Physicians are required to ensure that identified sexual or needle-sharing contacts of patients with HIV or AIDS are notified of their risk by one of the following methods: • patients can notify at-risk contact(s) personally, with physician verification; • physicians can notify exposed contacts alone or with patients; • contacts can be notified confidentially by a trained public health counselor through the HIV Partner Notification Program. • Patients’ disclosure of their contacts’ identities is voluntary and they are not subject to penalties for failure to disclose. • Physicians must inform patients that any contacts they identify will be notified of their risk, regardless of patients’ wishes to the contrary. • Neither physicians nor Department of Health personnel may disclose to contacts the identities of infected patients. • Providing information that prevents harm to unidentified others at risk (e.g., public health or public safety reporting). In some instances, the potential danger is to the general population, rather than to specified individuals. To protect the public health and safety, New York State law requires that health care providers report • suspected cases of child abuse and neglect; • wounds that are the result of gun shots, knives or other pointed instruments; • burn injuries of specified severity; and • every case of reportable communicable diseases specified in the state health law. References American College of Physicians. Ethics Manual, 3rd ed. (Philadelphia: American College of Physicians, 1993), cited in Amy B. Witman, Deric M. Park and Steven B. Hardin, “How Do Patients Want Physicians to Handle Mistakes?,” Arch Intern Med (Dec 9/23, 1996):156: 2565-69, at 2567. Baylis F, “Errors in Medicine: Nurturing Truthfulness,” J Clinical Ethics 1997;8(4) 336340. Lisa Belkin, “How Can We Save the Next Victim?,” The New York Times Magazine, June 15, 1997, 28-70, Bok S. “The Limits of Confidentiality,” The Hastings Center Report, Feb. 1983, 24-31. Brennan TA, Sox CM and Burstein HR, “Relation Between Negligent Adverse Events and the Outcomes of Medical-Malpractice Litigation,” New England Journal of Medicine (1996): 335(26):1963-1967. Brennan TA. et al., “Incidence of Adverse Events and Negligence in Hospitalized Patients: Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I,” New England Journal of Medicine 1991:324(6):370-76. Cullen S, Klein M. “Respect for Patients, Physicians and the Truth,” in Munson R, Intervention and Reflection: Basic Issues in Medical Ethics, Sixthth Edition. Belmont, CA:Wadsworth, 2000, pp. 435-442. Freedman B. “Offering Truth” in Ethical Issues in Modern Medicine, Sixth Edition, Steinbock B, Arras JD, London AJ, eds. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2003, pp. 76-82. Lagasse RS et al. “Defining Quality of Perioperative Care by Statistical Process Control of Adverse Outcomes,” Anesthesiology May 1995: 82(5)1181-88. Leape LL et al. “The Nature of Adverse Events in Hospitalized Patients: Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study II,” New England Journal of Medicine 1991:324(6):37784. Roscoe LA, Krizek, TJ, “Reporting Medical Errors,” Bulletin of the American College of Surgeons 2002;87(9):12-17. Siegler M, “Confidentiality in Medicine—A Decrepit Concept,” New England Journal of Medicine 1982;307:1518-1521. Charles Vincent, Magi Young and Angela Phillips, “Why do people sue doctors? A study of patients and relatives taking legal action,” The Lancet (1994):343:1609-13.