The New, New City - Pockets - Distributed Workplace Alternative, Inc.

advertisement

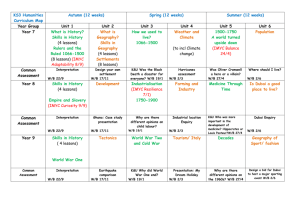

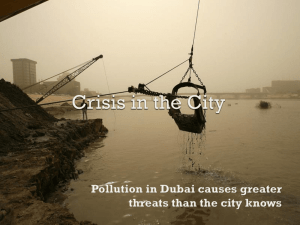

The New, New City The Architecture Issue By NICOLAI OUROUSSOFF New York Times June 8, 2008 NEW SHENZHEN ENCIRCLES OLD: In the center, one of the city’s original urban villages, with its signature “handshake buildings” — so close together you could reach across to your neighbor. - Sze Tsung Leong for The New York Times “Don’t tell anyone,” Rem Koolhaas said to me several years ago as we headed down the F.D.R. Drive in New York, “but the 20th-century city is over. It has nothing new to teach us anymore. Our job is simply to maintain it.” Koolhaas’s viewpoint is widely shared by close observers of the evolution of cities. But not even Koolhaas, it seems, was completely prepared for what would come next. In both China and the Persian Gulf, cities comparable in size to New York have sprouted up almost overnight. Only 30 years ago, Shenzhen was a small fishing village of a few thousand people, and Dubai had merely a quarter million people. Today Shenzhen has a population of eight million, and Dubai’s glittering towers, rising out of the desert in disorderly rows, have become playgrounds for wealthy expatriates from Riyadh and Moscow. Long-established cities like Beijing and Guangzhou have more than doubled in size in a few decades, their original outlines swallowed by rings of new development. Built at phenomenal speeds, these generic or instant cities, as they have been called, have no recognizable center, no single identity. It is sometimes hard to think of them as cities at all. Dubai, which lays claim to some of the world’s most expensive private islands, the tallest building and soon the largest theme park, has been derided as an urban tomb where the rich live walled off from the poor migrant workers who serve them. Shenzhen is often criticized as a product of unregulated development, better suited to the speculators that first spurred its growth than to the workers housed in huge complexes of factory-run barracks. Yet for architects these cities have also become vast fields of urban experimentation, on a scale that not even the early Modernists, who first envisioned the city as a field of gleaming towers, could have dreamed of. Sze Tsung Leong for The New York Times The Frontier: Southwestern Shenzhen under construction. “The old contextual model is not very relevant anymore,” Jesse Reiser, an American architect working in Dubai, told me recently. “What context are we talking about in a city that’s a few decades old? The problem is that we are only beginning to figure out where to go from here.” The sheer number of projects under construction and the corresponding investment in civic infrastructure — entire networks of new subway systems, freeways and canals; gargantuan new airports and public parks — can give the impression that anything is possible in this new world. The scale of these undertakings recalls the early part of the last century in America, when the country was confidently pointed toward the future. But it would be unimaginable in an American city today, where, in the face of shrinking state and city budgets, expanding a single subway line can seem like a heroic act. “In America, I could never do work like I do here,” Steven Holl, a New York architect with several large projects in China, recently told me, referring to his latest complex in Beijing. “We’ve become too backward-looking. In China, they want to make everything look new. This is their moment in time. They want to make the 21st century their century. For some reason, our society wants to make everything old. I think we somehow lost our nerve.” Holl has reason to be exhilarated. His Beijing project, “Linked Hybrid,” is one of the most innovative housing complexes anywhere in the world: eight asymmetrical towers joined by a network of enclosed bridges that create a pedestrian zone in the sky. Yet this exhilaration also comes at a price: only the wealthiest of Beijing’s residents can afford to live here. Climbing to the top of one of Holl’s towers, I looked out through a haze of smog at the acres of luxury-housing towers that surround his own, the kind of alienating subdivisions that are so often cited as a symptom of the city’s unbridled, dehumanizing development. Protected by armed guards, these residential high-rises stood on what was until quite recently a working-class neighborhood, even though the poor quality of their construction makes them seem decades old. Nearby, a new freeway cut through the neighborhood, further disfiguring an area that, however modest, was once bursting with life. “If you take Venturi’s ideas about the city,” Holl said, referring to Robert Venturi’s groundbreaking work, “Learning From Las Vegas,” which called on architects to reconsider the importance of the everyday (strip malls, billboards, storefronts), “and put them in Beijing or Tokyo, they don’t hold any water at all. When you get into this scale, the rules have to be rewritten. The density is so incredible.” Because of this density, cities like Beijing have few of the features we associate with a traditional metropolis. They do not radiate from a historic center as Paris and New York do. Instead, their vast size means that they function primarily as a series of decentralized neighborhoods, something closer in spirit to Los Angeles. The breathtaking speed of their construction means that they usually lack the layers — the mix of architectural styles and intricately related social strata — that give a city its complexity and from which architects have typically drawn inspiration. In Dubai, for instance, what might once have been the product of 100 years of urban growth has been compressed into a decade or so. Given such seismic shifts, even the most talented architects can seem to flounder for new models. No one wants to return to the deadly homogeneity associated with Modernism’s tabula rasa planning strategies. The image of Le Corbusier hovering godlike above Paris ready to wipe aside entire districts and replace them with glass towers remains an emblem of Modernism’s attack on the city’s historical fabric. Yet the notion of finding “authenticity” in a sprawling metropolitan area that is barely 30 years old also seems absurd. How do you breathe life into a project at such a scale? How do you instill the fine-grained texture of a healthy community into one that rose overnight? Cities like these, built on a colossal scale, seem to absorb any urban model, no matter how unique, virtually unnoticed. A project that could have a significant impact on the character of, say, New York — like the development plans for ground zero — can seem a mere blip in Beijing, which has embarked on dozens of similarly sized endeavors in the last decade alone. “The irony is that we still don’t know if postmodernism was the end of Modernism or just an interruption,” Koolhaas told me recently. “Was it a brief hiatus, and now we are returning to something that has been going on for a long time, or is it something radically different? We are in a condition we don’t understand yet.” For architects faced with building these large urban developments, the difficulty is to create something where there was nothing. If much of contemporary architecture depends on sifting through the cultural and historical layers that a site accumulates over time — whether neo-Classical monuments or Socialist-era housing — what can be done if there is nothing to sift through but sand? In a recent design for a six-and-a-half-square-mile development in Dubai called Waterfront City, Koolhaas proposed creating an urban island inspired by a section of Midtown Manhattan. The design linked a dense grid of conventional towers to the mainland by a system of bridges. A series of stunning “iconic” buildings — a gigantic, hollowed-out Piranesian sphere at the island’s edge; a spiraling tower that winds around an airy public atrium — were intended to give the city a distinct flavor. Koolhaas said he hoped, in this way, to infuse this entirely new development with something of the feeling of an older city. But while the outlines are intriguing, he is still coming to terms with how to create an organic whole. In the early stages of the design, Koolhaas experimented with somewhat conventional models of public space: a boardwalk along the island’s perimeter, a narrow park cutting through its center, classical arcades lining the downtown streets. But the majority of Dubai’s inhabitants are foreign-born, and the arcaded streets could easily suggest a theme-park version of a traditional Arab city. Koolhaas is painfully aware of how hard it is to escape the generic. “A city like Dubai is literally built on a desert,” Koolhaas conceded when I asked him about the project. “There is a weird alternation between density and emptiness. You rarely feel that you are designing for people who are actually there but for communities that have yet to be assembled. The vernacular is too faint, too precarious to become something on which you can base an architecture.” Koolhaas says he hopes that the plan will gain in complexity as the buildings’ functions are worked out; he says he was thrilled to learn that the government wanted both a courthouse and a mosque on the island. “Another option that I personally find very interesting,” Koolhaas told me, “is the modernist vernacular of the 1970s — buildings that once you put them in Singapore or Dubai take on totally different meanings. Some of the modern typologies work in Asia even though they are totally dysfunctional in America. Typologies we’ve rejected turn out to be viable in other contexts.” The challenges of building what amounts to a small-scale city from scratch are compounded by the realities of working in a global marketplace. An architect of Koolhaas’s stature may be grappling simultaneously with the design of a television headquarters complex in Beijing, a stock exchange in Shenzhen and a 20-block neighborhood in Dubai, as well as a dozen buildings in Europe. The intense competition for these commissions means that architects are often forced to churn out seductive designs in weeks or months, tweaking their models to fit local conditions. Several years ago, the London-based, Iraqi-born architect Zaha Hadid received a phone call from a Chinese developer asking if she might be interested in designing a 500-acre urban development on the outskirts of Singapore. Hadid had never met the developer before. She was soon working on the master plan for “One North,” a mixed-use development with a projected population of about 140,000. Located on what was once a military site, Hadid’s design conjured a high-tech mountainous terrain. Dubbed the “urban carpet,” it was intended to blend office and residential towers and highways and public parks into a seamless whole. Against the rigid lines of the traditional street grid, the sinuous curves of the freeways suggested a more fluid, mobile society. The rooftops, whose heights were subject to stringent regulations, looked as if they were cut from a single piece of crumpled fabric, giving the composition a haunting unity. “We wanted to create a complex order rather than either the monotony of Modernism or the chaos you find in contemporary cities,” Hadid said. Yet once construction began, the design of the buildings was left to local architects hired by the developer. As the towers rose in clusters scattered across the site, it was difficult to read the formal intent. With more than 20 blocks now complete, parts of the city look surprisingly conventional. Hadid revived the concept several years later, when she won a competition to create a 1,360-acre business district in a former industrial zone on the outskirts of Istanbul. This time, the context was more promising: a hilly landscape at the edge of the sea flanked by older working-class neighborhoods on either side. To allow the development to grow in a more natural way than at One North, it would be built in phases that would begin at the waterfront and spread inland, eventually connecting to the street grid of the older neighborhoods. In an effort to preserve the texture of her original concept, Hadid developed a series of building prototypes, including a star-shaped tower and a housing block organized around a central court, and staggered the heights of the buildings to reflect the existing terrain. If Hadid’s plan is formally inventive, it is still unclear whether it has escaped the homogeneity that was a hallmark of Modernist urban-renewal projects. Its sheer size coupled with the fact that the shapes of the buildings were conceived by a single architect means the result may well be more uniform, and ultimately more rigid, than Hadid intended. Indeed, contemporary architects’ urban plans may be less tied to location than they would like to admit. When a Chinese developer approached the New York-based Jesse Reiser and Nanako Umemoto to design a 1,235-acre development in Foshan, on the Pearl River Delta, they (with a Chinese partner) came up with a system of urban “mats”: a multilayered network of roads and low-rise commercial spaces, topped by a park surrounded by residential and commercial buildings. The park followed the contours of the roadways below; sunken courtyards allowed light to spill down into the underground spaces. Last year, the Chinese project fell through, and Reiser and Umemoto reworked the idea for a developer in Dubai. The layout was reconfigured to fit the new waterfront site; souks were added as a nod to local traditions. The result is a remarkably nuanced view of how to knit together the various elements of urban life, but it also seems as if it could exist anywhere. The walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods celebrated by Jane Jacobs may seem impossibly remote, but encouraging signs of a more textured urban reality can still be found. Take Holl’s Linked Hybrid in Beijing, for example, which has a surprisingly open, communal spirit. A series of massive portals lead from the street to an elaborate internal courtyard garden, a restaurant, a theater and a kindergarten, integrating the complex into the surrounding neighborhood. Bridges connect the towers 12 to 19 stories above ground and are conceived as a continuous string of public zones, with bars and nightclubs overlooking a glittering view of the city and a suspended swimming pool. “The developer’s openness to ideas was amazing,” Holl says. “When they first asked me to do the project, it was just housing. I suggested adding the cinematheque, the kindergarten. I added an 80-room hotel and the swimming pool as well. Anywhere else, they’d build it in phases over several years. It’s too big. After our meeting, they said we’re building the whole thing all at once. I couldn’t believe it. We haven’t had to compromise anything. “But what makes it possible is the density. The Modernist idea of the street in the air that became a place of social interaction never worked in Europe. Beijing is so dense that I can keep all of the shops functioning on the street, and there’s still enough energy to activate the bridges as well.” Holl is continuing to explore these ideas in another megaproject, this time on the outskirts of Shenzhen: a zigzag-shaped office complex propped up on big steel columns that make room for a dreamy public garden. The density in much of Shenzhen can make Beijing look spacious. The imposing skyline of glass-and-steel towers, plastered with electronic billboards, was built mostly within the last decade, part of the boom that followed foreign investment in the area, when it was declared a special economic zone in the early ’80s. The Chinese government initially allowed many of the small villages that lined the delta to hold on to their land. As land values rose around them, the villagers remained in their increasingly populated districts, where they built cheap, and often instantly decrepit, towers that were so close together they were dubbed “handshake buildings”: you could literally reach out your window and shake hands with your neighbor across the street. The villages are poignant testimonies to the hardships that young workers, recently transplanted from the countryside, face in the new China. Many live packed a half dozen or more in one-bedroom apartments. But if Shenzhen is an emblem of what can happen when free-market capitalism is allowed to run amok, it is also an example of the spontaneous creativity that occurs when people are left to fend for themselves. On a recent visit, the alleyways, dark and claustrophobic, were thick with shops. Elderly people played mah-jongg on card tables in the street; two young children sat at a small desk doing their homework in a tiny storefront that doubled as their bedroom. Wenyi Wu, a young architect working for a Chinese firm called Urbanus, led me around the area. The firm has been studying how people carve a living space out of seemingly inhospitable environments, hoping to develop an urbanist model more deeply rooted in the spontaneity of everyday life. He took me to a small museum Urbanus designed on the outskirts of the city. A series of stepped galleries stand at the base of a hill between an urban village and some banal housing complexes above. A series of long ramps pierce the building, joining the two worlds. More ramps encircle the exterior, so that you have the impression of moving through a system of loosely connected alleyways. The idea was to transform the unregulated character of the urban village into something more formal and humane — to extract the essence of its character without romanticizing the squalor. The circuitous paths of the ramps echo the surrounding alleyways; the layout of the galleries suggests the footprint of the migrant workers’ housing but on a more intimate scale. Other architects, hoping to build in ways that reflect an emerging vernacular, are taking a similar approach, looking at more modest and more informally constructed urban neighborhoods for inspiration. Shumon Basar, a London-based critic and independent curator, recently described a number of small, unplanned settlements in and around Dubai. The dense and gritty neighborhood of Deira, for instance, has little in common with Sheikh Zayed Road and its fortified glass towers. Built mainly in the 1970s, Deira’s low concrete structures and labyrinthine alleyways are home to a lively population of Southeast Asian workers. Similarly, the thriving, traditionally Muslim middle-class neighborhoods of Sharjah, the third-largest city in the United Arab Emirates, were built without the flashiness of more recent developments. Basar wonders if, despite their modesty, these areas could form the basis for a fresh urban strategy based neither on imported Western models nor on clichés about local souks. As Holl told me recently in his New York office, working on a large scale doesn’t mean that the particulars of place no longer matter. “I don’t think of any of my buildings as a model for something, the way the Modernists did,” Holl said. “If it works, it works in its specific context. You can’t just move it somewhere else.” But is site specificity enough? “The amount of building becomes obscene without a blueprint,” Koolhaas said. “Each time you ask yourself, Do you have the right to do this much work on this scale if you don’t have an opinion about what the world should be like? We really feel that. But is there time for a manifesto? I don’t know.” Nicolai Ouroussoff is the architecture critic of The New York Times.