How do students learn? Psychologists and educators have lavished

advertisement

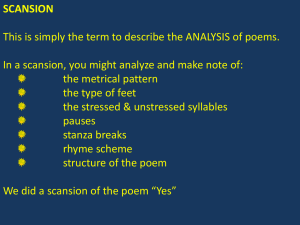

“I am ill at these numbers”: Reflections on a Web-Based Scansion Unit Barbara Mathieson Southern Oregon University mathieson@sou.edu How do students learn? Attempting to answer this question, psychologists and educators have lavished energy in recent years on mapping the requirements for successful learning moments and searching for pitfalls in less effective cognitive experiences. While exploring the broad, general methods by which teachers can guide student comprehension, pedagogical research has also focused on the specific questions raised by our burgeoning computer culture and by the use of new technological strategies for enhancing instruction. The Internet, in particular, has been lauded and debated as the academic Promised Land, with its vision of multimedia alternatives to purely verbal instruction and the promise of hypertext’s associative freedom of thought. With the hope of discovering a more successful method of teaching scansion than my previous classroom cycle of explanation and drill, I embarked upon a project of creating a Web-based unit for my students. Although all English majors in my department presumably are exposed to the basic elements of scansion in the introductory course for majors, painful experience in my upper division classes on Shakespeare and early modern literature has revealed that even after several hours spent “refreshing” those concepts in the classroom, my students still struggle with the application. How wonderful, I decided, to offer them a self-paced study tool, constructed around a foundational sequence of skills and accessible on the Internet. Students could proceed at their own paces, pausing to review concepts and activities difficult for them. More Mathieson 2 experienced poetry students could progress rapidly to the complex topics that it was my goal to impart: a comprehension of the intricate care taken by traditional poets in shaping the rhythmic sounds of their verse, and the vitality with which those metrics actually reflect, shape, and enhance the meaning of a verse passage. In my assumption, the Web unit would serve to supplement and even replace actual contact time in the classroom spent reviewing basic skills: students would use the unit as a tutorial to understand and apply scansion techniques, I imagined, freeing more class time for such sophisticated substantive concepts as poetic artistry in employing metrical variation. In practice, however, the results last quarter were disheartening. No more students than in previous years demonstrated a genuine grasp of the concepts and mechanics. This paper represents my attempt to understand the gap between idea and reality. Technological educators caution against simply “repackaging” traditional learning products and strategies for the computer. Shirley Alexander, for example, discourages “taking an existing book (with or without pictures) and simply adding hypertext or hypermedia links,” since it may be slow to load and frustrating for the user (5). The nature of hypertext, in particular, seems to demand a completely new logical structure for Web-based tools, one that is associative rather than sequential, and thus “matches human cognition; in particular, the organization of memory as a semantic network in which concepts are linked together by associations” (Kearsley 23). Yet scansion is not a complete knowledge base but a technique, a strategy built upon a series of skills and steps that do seem sequential of necessity, and I remain unable to imagine a free-form associative route to the goal. The ability to incorporate auditory elements, to Mathieson 3 include the experience of actors reading the passages aloud as students view the words on the screen, on the other hand, seemed to offer a new and exciting use of the Web to experience the sound patterns so essential in poetry. Diana Laurillard suggests that multimedia capability, which permits the comparison of text with an audio component or visual image, provides a true associative experience for the student (127). Further, juxtaposing written explanations and the texts of verse passages with audio units brings into play several of the “multiple intelligences” theorized by Howard Gardner to exist across the population of learners. Unlike the narrower range of abilities measured by traditional IQ tests, Gardner argues, a variety of kinds of intelligences, and hence of learning styles, are present in varying mixes in different students. Instead of relying solely upon linguistic strategies, the Web site with audio enhancements could also appeal to musical/rhythmic intelligence, and thus communicate more fully to a greater number of students. I introduced a simple questionnaire through which to explore the disappointing results from the students’ point of view, as well as to test for basic comprehension. The questionnaire combined a series of queries followed by a brief exercise in which students were asked to demonstrate their ability to apply the principles of scansion. In a class of 30, nearly all students admitted to using computers regularly, a reversal from the first classes in which I introduced computer-based discussion groups five years ago. All but one student this year made use of e-mail, and most used a computer for word processing. In addition, 24 of the 30 claimed to use the Web for research. When queried about comfort level with computers, two-thirds of the students claimed to feel comfortable, although, as one said, “I stay within the familiar modes, only trying new things when Mathieson 4 forced.” Only two openly expressed resistance toward computers. Mistrust, hostility, and extreme lack of confidence, strong elements in my attempts to incorporate educational technology five years ago, do not seem to be significant factors in the present, a genuine gain for the potential of computer-based learning. As for scansion skills, all but five students in the class said they had studied scansion previously; of the 25 with prior exposure, however, 20 considered themselves “beginners” or “not very skillful” in actually scanning verse at the start of the course, displaying widespread lack of confidence. Four of the five who classified themselves as “skillful” validated their own judgment in the exercise. These skilled students, like nearly all of their less experienced classmates, claimed to find my scansion site clearly laid out, user friendly, and useful. “I felt pretty confident, but I needed some refreshing,” wrote one. “The site was very helpful and well-organized,” many agreed. Some students openly expressed appreciation for the site and for the practice exercises embedded in it. “I printed out the whole site and put it in my English folder. Thanks!” wrote one student, echoed by several others, unfortunately ignoring in the process the audio elements which to me make the site distinctive and useful. While accessing the audio units posed problems for some, others found them useful and exciting. One effused that the sound bites were “awesome, and what I needed to help me with stresses.” When I surveyed the actual scansion exercises, however, results were mixed. About three-fourths of the class did provide scansions of a short passage that seemed valid or at least in the ballpark. However, some notable deficiencies that I had not expected quickly surfaced. Although the exercise sheet itself reinforced the passage’s use of blank verse, a term that was clarified both in class and on the Web site, four students Mathieson 5 divided the lines into irregular feet (1 to 4 syllables) and others used odd numbers of feet (3 or 4 to a line). Others “discovered” arbitrary rhythmic patterns rather than iambs. To my chagrin, I realized that the level of basic skill which I had assumed sometimes did not exist. Several proved unable to correctly divide words into syllables: a number of them scanned “miserable” as two or three syllables, while two others unaccountably split “which” and “wrath” after the first two consonants. The mistakes and confusions that my students exhibited offered me a wealth of new information about the content of the site, about gaps in my explanations and places where my assumptions about their learning did not match the reality. As such, additional work on the content, providing fuller explanations and more examples, will smooth the learning process to some degree. More to the point, however, was the repeated request in the “comments” section simply to go over the basic scansion material in class. Confidence remained low, even in students who performed adequately. Wrote one, “The site is definately set up very nice and easy (sic). Unfortunately, as a user I still seem to have trouble with scansion regardless of the useful and interactive site.” Several students expressed frustration with the underlying process of sorting out explanations on their own in front of a computer screen. “I just don’t learn off a computer” bemoaned one student, whose sample scansion exercise fully corroborated that claim. Even two students who submitted excellent exercises requested more classroom time reviewing scansion. In her excellent study of education and technology, Rethinking University Teaching, Diana Laurillard argues that any new teaching strategy must acknowledge the underlying pattern of all true learning moments. Laurillard moves away from the traditional vision of education as “imparting knowledge” (13) to outline a series of Mathieson 6 interdependent activities, mediated by the teacher but situated within the student, which occur as genuine or “deep” learning takes place. In addition to being introduced to the goals and methods of any learning project, students must also be given the opportunity to act on the world with their nascent understanding, to receive feedback, both intrinsic and extrinsic, and to learn to reflect on the cycle of goals-action-feedback in order to revise their understanding. While the scansion site offers a significant number of exercises upon which students can practice their skills, the feedback offered was delayed and merely extrinsic (my evaluation and comments upon their efforts after they printed and submitted scansion exercises), and the opportunity to revise was left solely to each individual’s initiative. What would on-line feedback look like? Simple “Right/Wrong” responses from the computer might work for syllable divisions or identifying accented syllables in single words, but are inappropriate and inadequate for the many interpretive choices involved in scanning more sophisticated passages. A true interactive capability, a vision of a future scansion site of which I can only dream, would allow students to identify a metrical pattern in a sample verse passage on line and then receive aural feedback from a computer that actually pronounces the passage as the student has marked the stresses. That would be true information about the student’s action, an empowering form of feedback, reflecting a genuine experience of having shaped an outcome with the opportunity to assess and revise. An Iowa State University study of student learning styles in Web-based learning found that “getting better grades than other students and expecting to do well were the two most highly rated motivators.” Thus, concluded the researcher, Web-educators Mathieson 7 should deliberately “maintain healthy student competition” (Shih 10). Strengthening this competitive edge might be beneficial as a supplement to the self-motivated and largely autonomous approach upon which I relied this year. Since my classroom style leans more toward cooperative techniques, however, I’m even more convinced by studies that suggest the need to incorporate classroom reinforcement for Web learning. This approach would enable me to make use of peer support rather than competition. Diana Laurillard stresses the necessity for regular repetition within the classroom of skills learned through technological tools, or “packages,” in order for retention to occur. “The learning students achieve in relation to a package should be followed through in subsequent teaching, so that it is not isolated from the rest of the course,” writes Laurillard. “Unless students use what they learn on a package, it will soon be forgotten, no matter how good it is, or how well they learned it initially. It has to become embedded in the way they think” (213). Similarly, a 1987 study by Biggs and Telfer insists that deep student learning requires “interaction with others, both peers and teachers,” in addition to a clear motivational context and a firm knowledge base (quoted Alexander 4). That interaction, the social context of learning, seems to have been a crucial missing element of my Web design. While focusing on imparting a knowledge base to my students and offering them a series of on-line exercises with which to practice, I unintentionally left them in isolation, without appropriate feedback that can enable them to revise and rethink their learning process, and without the classroom support that enables the techniques to become embedded. I need to integrate more fully the work performed on my Web site Mathieson 8 into the classroom, where simple human interaction can provide the level of feedback and interpersonal context needed. An article in a recent issue of the Journal of Educational Computing Research defined the emerging consensus quite clearly. The authors argued that “technologies in and of themselves rarely bring about substantial change in teaching and learning.” They continued, “the impact of technology on specific aspects of teaching and learning can be usefully understood only in context. Technologies matter only when harnessed for particular ends with the social contexts of schools” (Honey, Culp, and Carrigg 11). I’m revising my strategy to use the scansion site to employ the power of that social context. Until that moment in the future when a genuinely intelligent and vocal computer can provide feedback, I plan to substitute human partners for the intelligent machine. Working with one or more peers, students in my next class will hear the passages they scanned read aloud by a fellow student as marked. The ensuing discussions will inevitably sort out confusions and flush out their shared questions for immediate response by the teacher. Given the emerging emphasis on human interactions to complement and support Web-based learning, such a strategy may actually surpass the intelligent machine of the future as a vehicle for feedback and a tool to increase motivation. Works Cited Alexander, Shirley. “Teaching and Learning on the World Wide Web.” 1995. (www.scu.edu.au/sponsored/ausWeb/ausWeb95/papers/education2/alexander/) 17 Feb 01. Mathieson 9 Gardner, Howard. Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. 2nd ed. New York: Basic Books, 1993. Honey, Margaret, Katherine McMillan Culp, and Fred Carrigg. “Perspectives on Technology and Education Research: Lessons from the Past and Present.” Journal of Educational Computing Research 23.1 (2000): 5-14. Kearsley, Greg. “Authoring Considerations for Hypertext.” Educational Technology 28.11 (November 1988): 21-24. Laurillard, Diana. Rethinking University Teaching: A Framework for the Effective Use of Educational Technology. New York: Routledge, 1993. Shih, Ching-Chun and Julia Gamon. “Student Learning Styles, Motivation, Learning Strategies, and Achievement in Web-Based Courses.” (http://iccel.wfu.edu/publications/journals/jcel/jcel990305/ccshih.htm) 17 Feb. 01