The NAADAC Code of Ethics - Distance Learning Center for

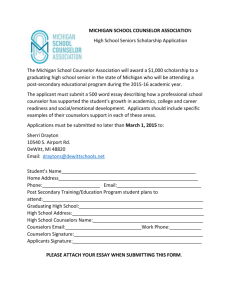

advertisement