chid495_transcendent..

advertisement

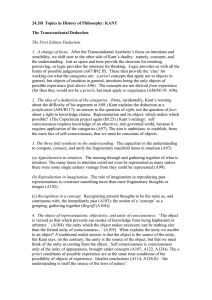

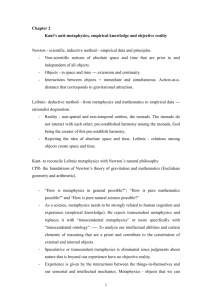

Reading Guide: CPR, Transcendental Logic: Analytic, pt.2 First Division: Analytic (219-224, §13) Before proceeding to the actual deduction of the pure concepts of the understanding Kant explains why an empirical deduction of the validity of them would be impossible, and that a transcendental one is necessary and difficult. 1. An empirical deduction would try to show how a concept is acquired through experience and reflection on it 2. A transcendental deduction explains which concepts can relate to objects a priori No Physiological Derivation Possible Both space and time and the categories cannot be traced to experience. Although Kant remarks on the groundbreaking move Locke opened up with his philosophy, enabling research into experience for concepts, this method cantor explain the intelligibility of experience – the “possession of a pure cognition” (221) Deduction of Categories harder than Space and Time The deduction of the categories is not as simple as those of space and time in the Transcendental Aesthetic. This is because space and time are forms or all possible intuition, which pertains to sense. The categories do not represent the conditions of possible empirical intuitions, but of all possible appearances in general (put another way, pure intuitions relate to all possible objects of empirical intuition, while the categories relate to all possible objects in general). Further, space and time could be proven via reflection on formal conditions of given appearances, but the categories must be shown to order those appearances a priori. In short, in the Aesthetic we could work back from experience to our transcendental exposition, but in the Analytic we cannot work back from experience, since we’re after the conditions of possibility of experience in general (and thereby are required to provide a transcendental deduction). (222, bottom – 223) The Focusing Question: How are subjective conditions of thinking objectively valid? Or How is it that our conditions of thinking yield the possibility of all cognition of objects”? It is clear that sensible objects of intuition must accord the formal conditions of our sensibility, but it is harder to show that they must also accord with the conditions of our understanding, since “intuition by no means requires the functions of thinking” (223). The Example of Cause Kant finishes this section by explaining the problem via an example. The example of cause poses the problem: either cause is a concept we bring to experience, or it is a mere fantasy of the brain, since there is no way to get from observed regularity in experience to a logical concept of causality at all. (224-226) Transition to the Deduction Kant begins by explaining that no “object of experience” is possible at all, since the empirical intuitions do not contain a principle for our synthesized representations of them in themselves, remarking: “hence concepts of objects in general lie at the ground of all experiential cognition as a priori conditions; consequently the objective validity of the categories, as a priori concepts, rests on the fact that through them alone is experience possible” (224, my italics) The lead in to the deduction explains that the unfolding of our actual experience is the illustration, but cannot be the deduction of the relation of concepts to objects - “Without this original relation to possible experience … [concepts’] relation to any object could not be comprehended at all” (225) Three Capacities of the Soul Kant identifies sense, imagination, and apperception as conditions of the possibility of all experience. The Aesthetic details the first, and the course of the deduction will address imagination and apperception, and particularly the latter. [For a general explanation of these, see the figure at the end of the previous handout] (245-246, §15) Combination Kant begins by explaining that while the manifold of representations can be provided by our affected sensibility, it [the manifold’s] combination cannot be derived from sensations or be found in the faculty of sense itself. The possibility of combination, then, arises from the “spontaneity” of the understanding, our faculty of thinking in action. Combination is the only representation that cannot be GIVEN through objects, but rather occurs by an act of the subject’s self-activity.* *[it is important to note here that this is NOT a “subject” understood as consciousness; this will be more clear below, but even the note Kant makes on this page belies this fact: “it is only the synthesis of this (possible) consciousness that is at issue here” (246). The synthesis cannot be a matter of consciousness, since it requires a ground.] Combination vs. Synthetic Unity The technical definition of combination is “the representation of the synthetic unity if the manifold,” and thus it is grounded on an original act of synthesis: “the original synthetic unity of apperception” (246). Thus, we have this picture of the dependency with respect to the understanding in general: Our judgments depend on categories. The unity of the categories (pure concepts) depends on combination. And the possibility of combination depends on synthetic unity. This will take us to the ground of the possibility of the understanding in general (whether in logical use or not). (246-248, §16) The Original Synthetic-Unity of Apperception In this section Kant describes the ground of empirical consciousness as well as all combination (in cognition) in a transcendental unity of self-consciousness. The language of psychology is used here, but the scholarship on the development of the deduction as well as comments by Kant himself show that this is not to be read psychologistically. [see p.247-248, “Namely, ….. the whole of human cognition.”] “The thought that these representations given in intuition all together belong to me means, accordingly, the same as that I unite them in a self-consciousness, or at least can unite them therein, and although it is itself not yet the consciousness of the synthesis of the representations, it still presupposes the possibility of the latter, i.e., only because I can comprehend their manifold in a consciousness do I call them all together my representations; for otherwise I would have as multicolored, diverse a self as I have representations of which I am conscious. Synthetic unity of the manifold … is thus the ground of the identity of apperception itself, which precedes a priori all my determine thinking” (248, my italics) Combination is an “operation of the understanding,” and understanding is thus a faculty for combining a priori, and bringing the given (manifold of representations) under the unity of apperception. This original apperception is an a priori “consciousness,” under which our common psychological/empirical consciousness stands as unified across the flow of intuitions. This also means we are “conscious a priori” of the “necessary synthesis” of the manifold of given intuitions. (248-250, §17) The Ultimate Principle of all Cognition: Original Synthetic Unity of Apperception “The first pure cognition of the understanding…on which the whole of the rest of its use is grounded, and that is at the same time also entirely independent from all cognitions of sensible intuition, is the principle of the original synthetic unity of apperception” (249) This means even the pure intuitions depend on this principle, which is to be sure an transcendental principle that is only negatively proved – it is the original necessary condition for any experience. (without this there would be no thought, just manifold sensation without any possible orientation) Kant remarks that other types of understandings are possible (nonhuman, such as ones that can intuit intellectually and have no need for this principle), but we can have no concept of them. (250-251, §18-19) Transcendental Unity of Apperception vs. Subjective Unity of Consciousness 1. The Original Synthetic Unity of Apperception (OSUA) has a transcendental principle, and designates the unity “through which all of the manifold given in an intuition is united in a concept of the object” 2. The Subjective Unity of Consciousness is a “determination of inner sense,” which has to do with the pure intuition of time and thus related to OSUA via the pure understanding. 3. These are both distinct from empirical consciousness, which is contingent and dependent on subjective (individual) experience. Note: 1 &2 have objective validity (for all human understanding), 3 is only subjective validity (for the individual alone) THUS: All logical judgments consist in the objective unity of the apperception OF the concepts contained therein, namely, the pure concepts of the understanding (§19) (252-254, §20-21) Summary and Remarks Section 20 is a summary waypoint for Kant, and he recaps the necessary relations in a single paragraph. Remark 21 is a more direct statement of the anti-psychological interpretation of the “self-consciousness” (OSUA) under which all other activities stand. He also remarks that he could not establish why we do not have intellectual intuition, why the categories rely on a given for cognition to take place. (254-256, §22-23) The Limits and Boundaries of Categories