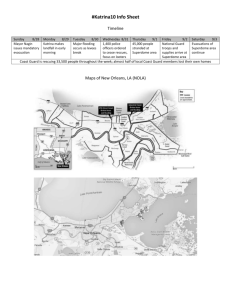

Day 1 – Friday August 26, 2005

advertisement

Say What? An analysis of the formation of rumor in response to Hurricane Katrina Lauren Flexon Marcinkoski Comprehensive Exercise James Fisher and Jerome Levi, advisors 3 April 2006 Abstract In August of 2005 Hurricane Katrina hit the city of New Orleans, Louisiana with violent fury. The destruction caused by the storm flooded the city, destroyed homes, and left many trapped without access to vital resources. This paper traces the formation of the rumor that the levee system was intentionally sabotaged during the aftermath of the hurricane. I examine the historical context of racial tensions and distrust of local infrastructure in New Orleans and the roles they play in the creation of rumor. Drawing on the theory of Marcel Mauss and Emile Durkheim that social institutions are exaggerated when a community is put under stress, I demonstrate the ways in which racial relations are perceived and communicated through story and rumor within the African-American community. 2 Acknowledgements I would like to dedicate this paper to my mother, my father, and Britta. They lived through this disaster with me and will always hold a special place in my heart. I would like to thank my advisors Jim Fisher and Jerome Levi for all of their wonderful advice and our department head Pamela Feldman-Savelsberg for letting me break down in her office. In addition, I owe a huge thank you to Hillary Elmore for my graphics. I would like to thank Adrienne Falcón and the rest of my Urban Sociology Class. And, I would like to thank my roommates Liz and Sarah and the rest of “the girls” for putting up with me through the comps process. A paper like this is not written by one person; it is a process helped along by all. To all of those who lived through Hurricane Katrina, may you find peace and live well. And to those who passed on, we remember you with respect and gratitude. 3 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements….………………………………………………………………….. 3 List of Figures……………………………………………………………………............ 5 Photographs…………………………………………………………………………. 6 - 8 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………9 - 20 Day 1 – Friday August 26, 2005……………………………………………….. 9 Day 2 - Saturday August 27, 2005…………….……………………………….. 9 Day 3 – Sunday August 28, 2005……………………………………………… 10 Day 4 – Monday August 29, 2005…….……………………………………….. 11 Day 5 – Tuesday August 30, 2005……….…………………………………….. 12 Day 6 – Monday August 31, 2005………….………………………………….. 18 Literature Review ………………………………………………………………... 22 - 25 Research Problem ……………………………………………………………….. 25 – 26 Methods…………………………………………………………………………… 26 – 27 Background ……………………………………………………………………… 27 – 31 New Orleans Demographics………………………………………………………32 - 34 Rumor…………………………………………………………………………….. 35 – 40 The Disaster Itself…………………………………………………………………42 – 45 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………45 – 47 Works Cited………………………………………………………………………. 48 – 50 Appendix A………………………………………………………………………… 51 -57 4 List of Figures Photographs 1 & 2 …………………………………...………………………………… 6 Photographs 3 & 4 ………………………...…………………………………………… 7 Photographs 5 & 6 ……………………...……………………………………………… 8 Map of Orleans Parish. ………………………………………………………………...21 Table 1 …………………………………………………………………………………. 33 Table 2 …………………………………………………….…………………………… 42 Appendix A ……………………………………………………………………………. 51 Figure 1 …………………………………………………………………….. 52 Figure 2……………………………………………………………………... 53 Figure 3 …………………………………………………………………….. 54 Figure 4……………………………………………………………………... 55 Figure 5……………………………………………………………………... 56 Figure 6……………………………………………………………………... 57 5 Photograph 1 Day 5 – Looting on Canal Street Photograph 2 Day 5 –Looting on Canal Street 6 Photograph 3 Day 6 – Rita and my mother on the way to the helicopter pad Photograph 4 Day 6 – View of the Superdome for the National Guard command post 7 Photograph 5 Day 6 – View of Interstate 10 from the helicopter Photograph 6 Day 6 – View of the Mississippi River from the helicopter 8 Day 1 – Friday August 26, 2005 As our train pulled into New Orleans station that morning, we were aware of a hurricane lurking in the Atlantic, but we had no idea that my family, Rita (a college friend) and I were about to live through one of the largest disasters in American history. My parents had come for a vacation from their stress-filled jobs and Rita and I had come to do what college students do best. Like my father said as he glanced at the Weather Channel, “Oh, come on. When is the last time a hurricane hit New Orleans?” Day 2 – Saturday August 27, 2005 By 6:00 AM the next morning we realized that my father was wrong…very wrong. My mother called Delta Airlines to schedule an evacuation flight and was lucky enough to find one leaving early Sunday morning. So, with a sigh of relief we tried to soak up as much of the Big Easy as we could in one day. Somewhere between the Voodoo Museum and Fifi Malone’s store for burlesque dancers my cell phone rang and my mother’s panicked voice pierced through the sunny afternoon. Delta Airlines had cancelled all flights leaving New Orleans. With the hurricane gaining strength in the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico, we knew we had to get out of the city. We called rental car companies, U-Haul, train stations, and bus stations. In desperation we tired to buy a car or charter a plan. But as the sun set that night, we became painfully aware that despite one’s resources, there was no easy way out of the Big Easy. 9 Day 3 – Sunday August 28, 2005 Sunday was a day that can only be described as complete and utter panic. Over night the little hurricane chugging through the Gulf had become a furious storm that would be the biggest to hit America yet. The roads were jammed with those lucky enough to have a way out, stores were quickly boarded up, and the local Walgreen’s was being cleaned out. While my parents still tried desperately to find any way to evacuate, Rita and I prepared for what we thought was the worst-case scenario: we bought enough bottled water to keep our little group happy for two or three days, a couple of flashlights, a few batteries, and some snacks. We filled the bathtubs with water so that we could flush the toilet if the power went out, and we bought a deck of cards to entertain ourselves. Around us, the city was a frenzy of activity. Because the mayor had waited for so long to call a mandatory evacuation, virtually the entire metropolitan area was trying to flee in the last few hours before the storm made landfall. Those who were unable to leave ran frantically from store to store in search of the dwindling supply of bottled water. However, our Bell Captain, Ron, assured us that the Fairmont Hotel was possibly the safest place to ride out a hurricane, and that they would stay open and fully staffed for the duration of the storm. Sunday night brought a flurry of emotions. Having no idea what to expect, we called friends and family and waited for the storm to arrive. In the early evening the rain began to tap at our windowpanes and we all went to bed that night as if we were simply sleeping through a thunderstorm. 10 Day 4 – Monday August 29, 2005 Around 4:00 AM Katrina lost her temper. We woke as a metal gutter went through the window of the room directly above us. The battered office building across the street had lost all of its windows and the curtains broke free and were dancing around the pool deck. Shingles of nearby rooftops soared by as gusts of wind tore apart the surrounding neighborhood. We joined the rest of the guests in the lobby away from any breakable windows and waited. When the storm cleared on Monday afternoon things did not seem as bad as we had expected. There was destruction all around us, but buildings were still standing, and most importantly there was no water in the streets. We thought that after maybe twentyfour hours the roads would clear and we would be on our way home. Due to the total lack of communication with the outside world and serious lack of communication within the city we did not realize how wrong our first post-hurricane assumptions were. When the National Guard walked into our lobby to ask us for supplies, we should have known, but it wasn’t until I saw a grown man in uniform sink into a chair and start to sob that the reality of our situation set in. They told us about the flooding in other parts of the city and people hacking through the roofs of their homes to escape rushing water. They had no supplies and no way of communicating with each other, much less local authorities. Ironically, they all had radios, but there was no way to charge them. Ron’s face sank as he listened. The hotel staff had been using most of its resources to make their guests comfortable under the assumption that people would be able to leave within twenty-four to forty-eight hours. There was enough food for Tuesday morning breakfast, but the water was already gone and the generator was only going to 11 last for one more day. With almost 400 people in the hotel, the staff was faced with a serious problem. Ron tried to bargain with the Guardsmen for diesel to fuel the generator, but they did not even have enough for themselves. The heat in the hotel was unbearable and as the thick walls gathered condensation, the rooms began to act like saunas. Worse, the elevators did not work and many elderly guests were unable to get up and down the stairs. Most guests had set up camps in the lobby or along the hallways like refugees. The sticky humidity and close quarters made it too hot to sleep, and my father and I sat up most of the night restlessly brainstorming about how to get out of the city. There was no way to live on M&Ms for a week. Day 5 – Tuesday August 30, 2005 After a couple hours of tossing and turning, around 6:00 AM we found our hotel suddenly surrounded by water. The basement had filled with sewage and the bar had become lake front property. The humidity of the Deep South turned the basement into a boiler room making the first two floors smell like the Port-A-Potties on Fat Tuesday. My father and I have never been the type of people who can sit around and wait easily, so we convinced Rita to put on her sneakers, get her camera, and come explore Canal Street with us. Plus, we needed batteries and if we could find a man in uniform, we might have a better idea of what was going on. Canal Street looked like a friendly neighborhood looting block party. People were smashing in doors and taking everything they could carry. There was an assembly line passing televisions and stereos out of the Walgreen’s and two heavily armed women guarded the jewelry store as they waited for their boyfriends to return with tools to open the security gate. 12 Farther down the street, we spotted a man with a CNN hat and a video camera under his arm filming the ordeal. Thinking that he might have access to information from the outside world, Rita and I made our way over to ask about what was going on. “Look girls, I don’t know any more than you do. I just got dropped in the middle of this to videotape,” he replied, irritated that we had interrupted his footage. And as he spoke, a bottle whizzed by his head. “Fucker! Either help us or get the hell out!” “You girls need to get out of here,” he said with a jerk of his head. “These black guys are going to kill you.” With that, he turned and sloshed towards a clothing store that was getting cleared out. The black men did not kill us. As a matter of fact, they gave us the right size battery for our radio and relayed information they had gotten from a policemen who had come through earlier. The water we were wading through had come from a break in the 17th Street canal levee and it was expected to keep rising slowly throughout the day. Back at the hotel, Ron had also gotten tired of sitting and waiting. So, he set out through the water in search of the canoe house in City Park. He came back with a canoe, two paddles, and a fantastic story about the amount of water in other parts of the city as well as rumors of even more levees breaking. “They say there’s going to be twenty-five to thirty feet of water in this area by 3:00 PM,” he exclaimed. “We should get everyone ready to move to the second floor Mezzanine” Some people moved and some people said they would wait and see. But for us, a miracle happened. Rita found an old calling card in her purse. And for some reason, it 13 would work to call out of the city when nothing else would. We managed to reach her boss at home who had already taken it upon herself to call up some clients with a helicopter. “Well, we have to get you out of the bayou before we’re going to be saying good bye to you,” she laughed on the other end of the phone. “All you have to do is get to the helicopter port on the roof the Superdome parking garage at precisely 8:00 AM tomorrow morning. Now, he’s only going to be able to land for about five minutes, so you have to be there or he’s going to leave without you. The Superdome is only about a mile from your hotel, so it shouldn’t be too hard to get there. They gave us an ID number for the flight so that National Guard will know you’re the right people. Call us when you get home. Good luck!” To someone from the outside, walking about a mile to the Superdome probably seemed easy. But to us, we would be wading, possibly swimming through sewage, human waste, gasoline, and debris to a place we had never been. And if we were late, we would be left right back where we had started. So, we decided it would be best to find the helicopter port in advance. The most direct route to the dome by map was impassible. There were places where the water was so deep that cars were floating down the street. So, we decided to go down Canal Street through the looters. By this time, the friendly neighborhood block party had turned into dozens of irate people taking anything and everything. We waded through floating manikins, discarded merchandise, and debris as shouts erupted from a nearby store where two boys had broken through the security gate. 14 “That’s my boy!” One man praised his son who brought out a bag full of loafers, handed them off, and went back for more. My father began to look worried when he saw a policeman making his way down the street and exclaimed, “Don’t you know we’re under Martial Law! Those kids will get shot if they get caught!” A man wearing a Rastafarian hat and a Bob Marley t-shirt turned and laughed. “Shit, these are the first damn police I’ve seen all day. Do you see how many of us are out here? Just let them try. You see what they did to us already. Just let them try. Martial Law my ass. Blow up the levees and then they gonna shoot us.” He splashed his hands in the water and asked animatedly, “Why this water not here until this morning? Answer me that! Why? My house was perfectly fine until this morning and now I got nothin’ left. Arrest me? Shoot me? Hell, go ahead.” “Yeah! Fuck them!” responded a kid coming out with more shoes. “See what happens when they fuck up my city! You take my shit from me and I’ll take yours from you. This is our city! We have a right to this shit after what they did to us!” “Hold on,” my father looked around. “You think this was done on purpose?” “Of course they did this on purpose,” replied the man in the hat. “There was no water here yesterday and now it’s everywhere. They do this to try to push the water out of uptown.” A small elderly woman spoke up, “I heard the explosion about 5:30 this morning. They think they savin’ all those rich folks up there. They leavin’ us to fend for ourselves. They don’t care ‘bout us.” 15 My father paused for a moment then said, “Well, alright. But at least be careful. Getting shot would not help the situation at all.” As we continued to make our way to the Superdome we passed dozens of people giving warnings not to go in. “They’re raping women in there,” one man warned emphatically. “You can’t take those girls there.” “I heard people are getting shot,” another man cautioned. When we finally arrived, the sight was sad, but not yet as violent as people had described. We helped two policewomen push a shopping cart to a ramp that led up to the dome. They were so desperate for supplies that they had resorted to sending people out to collect band-aids, antiseptic, and whatever else they could scavenge out of local stores for the 30,000 refugees crowded into the stadium. A few volunteer citizens were picking up stranded people by boat and bringing them to the shelter of the dome and every once in a while one would pull up to the ramp carrying dehydrated passengers. One boat driver had made a makeshift gurney out of plywood for a man who was so dehydrated that he could no longer bear the weight of his own head. He let it hang limply onto the floor of the fiberglass fishing boat with his swollen tongue protruding from his grey, cracked mouth. People had started to crowd around the outside walkways of the stadium to escape the foul odor inside the dome. The sewer system had backed up into the stadium and the intense heat of the Louisiana summer caused the stench to waft for blocks. Walking up the ramp, the smell of human feces, vomit, and body odor hit us like a wall. As soon as we found someone who could point us in the general direction of our helicopter pad, we 16 headed back towards the hotel to escape the smell and the pathetic sight of 30,000 people trapped inside a building with their own waste and no resources. On our return trip, we hit a slight snag in our plans. The sign from the Hyatt hotel had fallen into the murky water and was bobbing up and down just far enough below the surface to be out of sight. Slightly ahead of Rita and I, my father walked right into the sharp metal edges that scraped the skin off his shinbones as it bobbed in the water. We had nothing with which to cover the wounds and had no choice but to keep sloshing through the waste filled water back to the hotel. By the time we returned, the cuts were already putrid and angry, a sure bet for infection. While we were gone, the hotel had started to run in crisis mode. One of the main problems that had evolved for the guests was the lack of access to medical care. Diabetics were running out of insulin, people with infections had no antibiotics, and my father was the only physician. An elderly black man sat quietly in the corner breathing the last of his oxygen from the final tank of his supply. My mother had been doing the best she could to keep everyone as comfortable as possible, but with no supplies, instruments, or even water, it was impossible to really help anyone. So out Ron went again into the night with his canoe, a bowie knife, and a lantern to find help. An hour later he returned followed by a National Guard truck that took away those who urgently needed immediate assistant. 17 Day 6 – Wednesday August 31, 2005 Wednesday began with bleak news. The people that we had loaded onto the National Guard truck had never made it to the triage hospital as we had hoped. They had been dropped in the middle of the Superdome with no medical assistance at all. With a miraculously working cell phone, they had phoned back to the hotel in search of help, but we were no longer able to contact them. Frustrated, my family, Rita, and I set out for the helicopter pad as soon as there was enough light in the sky. There was nothing we could do for those that never made it to the hospital, but I couldn’t help feeling guilty as I sloshed down Canal Street filled with hope that we would soon be leaving this Armageddon. The street was almost empty at the early morning hour except for a man resting on top of a garbage can and a few National Guard. As we neared the man, I realized that he was holding his bleeding head in his hands as the National Guard looked on, unable to help without supplies or any way to transport him. Ron had offered to escort us back to the Superdome and the helicopter pad with his canoe so that we would not have to swim in the deep places. As it turned out, we were wise to have taken him up on is offer. We attempted to walk up the same ramp as the day before so that we could make our way over to the helicopter pad, but a National Guardsman stopped us. “You can’t go in there,” he said to my father sternly. “Look we have to get in there,” my father responded. “We have a helicopter coming to pick us up. The flight number is…” The guard stopped him and leaned closer thinking that the rest of us could no longer hear him. 18 “No, I mean you can’t take those girls in there. They won’t come back out.” Surprised, my father looked around him, “but how are we going to get there?” “You’re going to have to swim.” Turning back to us my father smiled and said, “Well, it’s a good thing we brought the canoe.” We couldn’t all fit in the canoe at once, so my father decided to be a gentleman and let the ladies go fist. The helicopter pad was on top of a parking garage directly adjacent to the Superdome and as we floated by, people above us began to shout down. “Hey, how much are they payin’ you man? Can I be next? I’d give anything to get out of here!” “Yo, why the hell do they get to go? What about us?” The first floor of the parking garage was completely under water, so Ron dropped us off at a stairwell. As we were climbing out of the canoe, a guardsman popped his head over the railing and pressed a finger to his lips. “Hurry,” he whispered. “You need to hide. People are starting to riot inside.” As he spoke, we could hear more shouts from the dome. “My husband,” my mother whispered back. “We have to wait for my husband.” We crouched down below a hand railing and waited for Ron to come back with my father. When they finally paddled up to the steps, we said a hasty goodbye and made a pact to give Ron a place to live when he escaped the city. Then, we turned and hurried up the stairs to the roof of the parking garage. As soon as we emerged from the stairwell, we were surrounded by men in army camouflage and hidden behind a command post. 19 The National Guard were starting to lose control of the people crowded in the Superdome and they didn’t want us to be seen leaving. Our helicopter had been grounded in Mobile, Alabama, so we had a long time to sit on the cement slab and watch the scene around us. We could see an overpass on Interstate 10 behind us where people had congregated to escape the flood waters. Every so often another refugee would wade through the chest high water to the on-ramp only to find himself in a crowd with no food or water. At one point, we watched as two desperate nurses dressed in blue hospital scrubs pushed on infant on a ventilator to the ramp, frantic to find help. But, help never came. People waited on the highway and suffered in the heat as the National Guard worked on top of the adjacent building, literally a stone’s throw away. When our helicopter finally came four hours later and we lifted off the ground, all we could see from horizon to horizon was water. The interstate looked like a ribbon, rising from the out of the murkiness every so often. Homes and tress had been flattened and replaced by flood. Sedans floated down the Mississippi out to sea along with a fleet of Fed-Ex trucks. We were leaving behind so many, helpless to their fates. We were hungry, dehydrated, and covered by infection from the contaminated water. My father would have trouble walking for the next few weeks because of the microbial infections that had spread up his legs. But the moment we lifted off the ground, I could not have been happier. We survived Katrina. 20 Source: Louisiana Geographic Information Center (LAGC) – http//lagic.lsu.edu Literature Review The study of disaster as a social phenomenon is a relatively new field and the literature on crisis and disaster has been described as “fragmented, ambiguous, conflicting and inconclusive” (Warheit 1988:196). Researchers fail to agree on a common definition for a “disaster” and frequently debate the difference between natural and technological disasters (Edwards 1998:117). It is argued that when a disaster occurs due to human error, victims tend to affix blame, thus causing more anxiety than disasters caused by environmental means (Edwards 1998:117). However, the social constructionists believe that the key to understanding how individuals respond to disaster lies in the meaning that they ascribe to the disaster, regardless of its cause (Clarke and Short 1993). In addition, as Margie L. Kiter Edwards points out, many researchers have trouble drawing comparisons between sociology, medical and psychiatric fields due to the lack of common definitions. Sociologists tend to describe mental health in a more general manner, defining it as “generic emotional stress” (Edwards 1998:117). However, psychiatric researchers often use more specified, medical definitions of emotional stress. The difference leads to many contradictions of research findings. For example, a person who cries as he or she sorts through damaged belongings or who takes time off from school or work would not be classified as showing signs of clinical depression by a sociologist, but may fall under specific definitions of clinical depression outlined by the field of psychology (Edwards 1998:117). These conflicting definitions often lead sociologists to form their own definitions of disasters and parameters of psychiatric classifications for specific use within their 22 specific papers. In his case study, Eric Klinenberg used his own specific definition of disaster in order to analyze the social conditions in Chicago that set the stage for the catastrophe caused by the intense heat wave in the summer of 1995. Using the city as a total social system that is the focal point of his study, Klineneberg presents a “multilayered analysis that integrates political, economic, and cultural factors with the individual and community level conditions that are prevalent in epidemiological reports” (Klinenberg 2003: 21). Rather than presenting a historical analysis of the disaster, he uses two theoretical principles “that hold that the case of the Chicago disaster can be used to open a broader inquiry into the life of the city” (Klinenberg 2003: 23). The first theory is that of Marcel Mauss and Emile Durkheim which states that extreme events (such as the Chicago heat wave or Hurricane Katrina) are “marked by ‘an excessiveness which allows us better to perceive the facts than in those places where, although no less essential, they still remain small-scale and involuted’” (Klinenberg 2003: 23). The second principle is based on the theory that social institutions tend to reveal themselves when a community is put under stress or in a situation of crisis. Michael Buraway uses these theories in his discussion of the extended case method by stating, “institutions reveal much about themselves when under stress or in crisis, when they face the unexpected as well as the routine” (Buraway 1998: 14). In his study of food shortages and famine, Robert Dirks uses the Law of Diversification which states “that disaster brings out the very best and the very worst in people; it exaggerates what is already there” (Dirks 1980: 22). He claims that the reason for many of the contradictions in disaster research is caused by the very essence of disaster. Because disasters put individuals under stress and “stress is conditioned; systems 23 exposed to the same stressor do not always react in the same way” (Dirks 1980: 24). Researchers must remember that disaster does not always trigger the same degree of stress among individuals and social systems. However, there are some universal similarities in responses to food shortages, regardless of the degree of stress generated by the disaster situation. Selye’s three phases of social response to food shortage exemplify these universal characteristics. The first stage is the “alarm stage” during which hyperactivation takes place in order to maintain a distressed social system. If the system does not find relief it moves into the “stage of resistance” to conserve energy and utilize defense mechanisms. Only those subsystems with appropriate coping skills will remain active during this stage. It is only when those subsystems that have remained active break down that the system enters the third stage called the “stage of exhaustion.” At this point the system is in a state of chaos just before it fails entirely (Dirks 1980: 26). These stages are meant to be used in an abstract manner in order to outline the “ways in which all living things adjust to drastic environmental change: first the manifold reactions to the initial shock, aimed at stabilizing the system; next, more specific and economical means as the system grids itself for protracted resistance; finally, a last ditch effort to sustain life after previous defenses collapse” (Dirks 1980: 26). Dirks concludes his paper with statements about the ways in which social norms break down in the face of food shortage as people become desperate to survive. Robbery is a common response as well as irrational violence against others within the community. Anthony Oliver-Smith groups disaster research into three categories: 1) “a behavioral and organizational response approach” 2) “a social change approach” and 3) 24 “a political economic/environmental approach, focusing on the historical-structural dimensions of vulnerability to hazards” (Oliver-Smith 1996: 303). Oliver-Smith claims that natural and technological disasters are increasing in their frequency and severity and that understanding them from an anthropological and societal viewpoint is crucial. He claims “disasters signal the failure of a society to adapt successfully to certain features of its natural and socially constructed environment in a sustainable fashion” (Oliver-Smith 1996: 303). And for this reason, sociologists need to understand how and why society sometimes fails to adapt to its environmental surroundings. “If a society cannot withstand without major damage and disruption a predictable feature of its environment, that society has not developed in a sustainable way” (Oliver-Smith 1996: 304). Understanding the sustainability of society is critical to its survival. Thus, the role of sociologists becomes crucial to the endurance of society as well. Research Problem For this paper, I use the city of New Orleans as a focal point in order to analyze why individuals reacted to the disaster by forming stories about the intentional sabotage of the levee system. I have modeled my investigation after Eric Klinenberg’s Heat Wave, and just as Klinenberg used his research to put the disaster into context historically, politically, economically, and psychologically, I use my research and personal experiences to analyze the effects of Hurricane Katrina. This paper is a case study that draws on studies of other disaster areas, but focuses specifically on the population directly affected within the city of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina made landfall in August of 2005. 25 Just as Klinenberg did, I use Marcel Mauss and Emile Durkheim’s theory on extreme events as well as the Law of Diversification outlined in Robert Dirks’s paper “Social Responses During Severe Food Shortages and Famine,” in order to show that the responses exhibited by the people of New Orleans during the Hurricane Katrina crisis were exaggerations of racial tensions, problems of poverty, and frustrations with political figures that already existed in the city before the storm. I explore the correlation between the previously existing social conditions in New Orleans and the violence and looting that erupted after the levee failure. Using work written about the social tensions caused by race and poverty within New Orleans prior to the disaster situation as well as quality of life surveys, I provide greater understanding about the formation of rumor among the African-American population. My goal is to put the rumor that the levee system was intentionally blown into historical and political context. In addition, I analyze factors affecting the perception of safety in the city of New Orleans during the days following the storm. Why did conspiracy theories about the levees form among the people trapped within the city? Why was there a common feeling of distrust towards the government prior to the storm? Did this feeling of distrust lead to much of the violence and looting that took place within the city? Methods Because the phenomenon of hurricane Katrina is such a recent event, there is little academic research available. Thus, much of the information used for this paper has come from news articles, census data, and my own personal experiences. I plan to draw comparisons to studies concerning other disaster situations and hope to find trends among 26 this research that will help to understand the reactions of the people of New Orleans. Using information concerning the demographics of the city of New Orleans from the United States Census Bureau and data released by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, I explore the relationship between the areas most affected by poverty and the areas in which the most people were trapped during the storm. In addition, I have conducted in depth interviews with victims of hurricane Katrina that have helped validate my research findings. These face-to-face interviews consisted of open-ended questions that allowed people to speak openly about what they feel were the most important aspects of their experience. The questions drew specifically on their perceptions of safety, access to valid information, and the ways in which they dealt with access to resources. Qualitative interviews are essential to the research process to understand and validly represent the views of those directly affected by the disaster situation. In order to properly understand a person’s perceptions about a specific circumstance, it is important to be able to ask open-ended questions and have the ability to explore further the responses given. Background Nestled between Lake Pontchartrain and the Mississippi River, New Orleans, Louisiana is a unique, multiracial, multiethnic city. The mix of ethnic groups and races brought fantastic culture to the city giving it distinctive food, music, and festivals. Famous for its Creole food and jazz music, New Orleans is a popular tourist destination, especially during the infamous Marti Gras festival. However, the diverse population of the city has formed a legacy of violent racial conflicts. Coupled with its vulnerability to 27 major floods, New Orleans has been plagued by natural disasters that have sparked racial tensions since the city was established in the early 18th century. Originally settled by the French, Louisiana became a crown colony in 1731. However, it was ceded to Spain in 1762 after the French and Indian war. Despite Spanish efforts, the French population continued to grow in Louisiana throughout the 18th century and as a result, the Spanish turned the colony back over to the French in the year 1800, only to see Napoleon sell the territory to the United States in 1803. The complicated early history of the state paved the way for a distinctive community of free men and women of color that gave it the largest black urban community in the United States up until the civil war. At the same time, Irish and German immigrants made homes in Louisiana by the thousands and Arcadians being pushed out of Nova Scotia by the British added to the cultural mixture (Encyclopedia of Urban America: 526). The Civil War brought devastation to New Orleans. From 1862 to 1865 federal forces occupied the city. Reconstruction brought defiance from the white community and in 1870 the white majority elected officials who refused to share the city with freed blacks. Shortly thereafter, the Jim Crow laws took effect, re-segregating the city. At the turn of the century, two major technological inventions began the process of shaping the racial geography of New Orleans as it is seen today. The Wood Pump, invented in 1917, allowed for the first time an effective means of draining swampy areas that were previously uninhabitable. With the simultaneous invention of the city streetcar system, the city expanded in ways that were otherwise impossible. Whites began to move into the newly open land, and because of public transportation blacks no longer needed to live near their employers and could live in the city (Spain 1979:89). During the Jim Crow 28 era “from the 1890s until the 1950s, New Orleans began adopting the residential patterns of large northern cities. The Black population became increasingly concentrated in the central city while whites settled the newly drained land surrounding the initial settlement” (Spain 1979: 83). In 1937, an effort by The Housing Authority of New Orleans to supply good quality, affordable housing was established. This project was the first to receive federal funding in the United States, and by 1941 five government subsidized housing projects existed in New Orleans. Though originally intended to be integrated housing developments, it was not long before black residents dominated the projects (Spain 1979: 90). As time went on, urban development, the building of interstates, and the Superdome pushed the majority of the back population reliant on public housing into the seventh and ninth wards of New Orleans. By the 1960s these communities had become and remain today over 90% African-American with an abnormally high number of people living below the official poverty line (Spain 1979). Though it may seem like an unlikely cause, weather patterns in New Orleans often brought social issues of class and race to the surface throughout the history of the city. Because it is located between two large bodies of water, many sections are prone to flooding and are protected only by man-made levees that do not always stand up to the tests of nature. The great Mississippi flood of 1927 demonstrated the extent of the power held by the white upper-class of New Orleans. The social climate in 1927 was precarious. The wealthy elite lived upriver in the Garden District in magnificent homes where blacks worked as servants and maids. 29 Located downriver, the French Quarter was the slum of the early twentieth century, housing the working class and ethnic communities. No American city resembled it. The river gave it both wealth and a sinuous mystery. It was an interior city, an impenetrable city, a city of fronts. Outsiders lost themselves in its subtleties and intrigues, in a maze of shadow and light and wrong turns … Modern poker, the most secretive of games, was invented there. New Orleans had not only whites and blacks but French and Spanish and Cajuns and Americans (the white Protestants) and creoles and Creoles of color (enough to organize their own symphony orchestra in 1838) and quadroons and octoroons. Each group lived an apparently separate existence. [Barry 1997: 213]. The Christian, white, male elite had formed “krewes.” These social clubs were the heart of the Mardi Gras celebration and held much political power. Membership in these clubs was exclusive and often secret. According to the New Orleans TimesDemocrat these clubs were composed of “gentlemen who know what’s what … and stand today, as [they have] always stood at the forefront of the social system of New Orleans” (Barry 1997: 217). The true power of New Orleans lay in those who held the money and those who held the money were the elite white Anglo-Saxon krewe members (Barry 1997). By January 1927, the Mississippi River had already reached flood conditions, and it would stay that way for 153 consecutive days. Severe weather systems pelted the entire Mississippi River valley with record-breaking amounts of rain for months. From Minnesota to Louisiana, devastating flood waters destroyed thousands of acres of land and left thousands homeless. Then on April 15, 1927 conditions turned from bad to worse: the city of New Orleans received 15 inches of rain in 18 hours. The levees held, but water filled the streets. Based on the amount of water seen in pictures, The New York 30 Times mistakenly reported that the Mississippi River had flooded the city. For days the city held its breath and waited as the mighty river swelled and churned (Barry 1997). On April 21, the head of the Corps of Engineers, General Edgar Jadwin, received the wire that he had been dreading: “Levee broke at ferry landing Mounds Mississippi eight a.m. Crevasse will overflow entire Mississippi Delta” (Barry 1997: 201). As a wall of water almost two hundred feet high surged through the levee on the Arkansas border, people in New Orleans began to panic. Levees protecting the city were already stressed to their limits and now it was only a matter of hours until the crevasse arrived. The wealthy elite rallied and decided there was only one thing that would save the city: break the levees down river from the city and flood the St. Bernard and Plaquemines Parishes in order to avoid flooding in the city itself. A gathering at city hall of wealthy business owners and krewe members was the final straw in the fate of the southern parishes. Only two members of the city council appeared and no one from either St. Bernard or Plaquemines parish was there to plead for the trappers and bootleggers that populated the marshy area. The socially privileged were the ones who made the decision. To the wealthy elite of New Orleans proper, the people of St Bernard Parish were not much of a sacrifice if it meant saving most of the cities homes and businesses. Dynamiting the levees would make over 10,000 people into refugees, but it would save the core of New Orleans. Though this event reaches back into the past, the white elite of New Orleans set a precedent. They made it clear that they could and would take advantage of the lower class in order to save their upper-class homes. 31 New Orleans Demographics New Orleans is a very unique city demographically. According to most recent census data, the African American population within the city accounts for 67.3% of the population whereas the average US metropolitan city has an African American population between 10% - 15%. In addition, 23.7% of the families living in New Orleans are considered below the poverty line, whereas the average American city has only between 8% and 10% of families living below the poverty line (www.factfinder.census.gov). Many claim that this heightened state of poverty and history of racial tensions is responsible for the abnormally large amount of crime and violence within New Orleans (DeParle 2005: 2). In his book, Creole New Orleans: Race and Americanization, Arnold R. Hirsch calls this racial tension “the ultimate irony…the defeat of segregation was accomplished only by an explicitly racial counterattack, an onslaught that killed Jim Crow but, when the dust had settled, left only ‘blacks’ and ‘whites’ facing each other across a daunting racial divide” (Hirsch 1992: 319). The law may have forbidden segregation, but the sad truth is that history has made New Orleans into a divided city. One glance at the distribution of race and class provided by the United States census makes it clear that the city is extremely segregated. Most districts either fall in the category of below 10% African- American or above 90% African-American. There are very few that fall in the middle area (www.factfinder.census.gov). In his 2003 report A Haunted City? The Social and Economic Status of African Americans and Whites in New Orleans, Silas Lee reports that social and economic demographics separate the city racially and often create barriers that restrain the advancement of the African-American population. As shown in Table 1, there is a 32 significant disparity between the black community income level and the white community income level. And because the African-American population makes up about 67% of the total population of New Orleans, we see that there must be a small populace of wealthy whites residing within the city. Table 1 Source: Lee, Silas. A Haunted City? The Social and Economic Status of African Americans and Whites in New Orleans. The disparity of income levels and the heightened instance of poverty among African-Americans is compounded by the difficulties in attaining education: “New Orleans has experienced a gain in educational attainment among residents since 1985. However, within the African-American community there exists a disparity in attainment and non-attainment...The fact that black college graduation rate has remained stagnant at 9% is reflective of the reality that as the black population has increased; there has not been an equivalent increase in the percentage of black college graduates” (Lee 2003: 5). Lee’s work demonstrates a quiet racism and classism within the city that creates frustration for the Black community. A survey of national news demonstrates more prevalent racial tensions found in New Orleans, Louisiana prior to Hurricane Katrina making landfall. The most recent 33 incident described three Caucasian bouncers at a popular nightclub who killed a young African-American. The event caused uproar from politicians and citizens: “There has been a perfect storm that has ripped the cover off race relations in New Orleans, the people who control public discourse here don’t like to talk about it. It’s not good for business. But this is really two cities” (Gold 2005). This quote, stated in November of 2005, just a few months prior to the disaster of Hurricane Katrina, became more than just a metaphor in the aftermath of the storm. The murder even grabbed the attention of international newspapers and a story in the May 20, 2005 issue of London’s The Independent featured the confrontation and a study commissioned by the mayor’s office that confirmed the claims of racial discrimination among New Orleans’ business owners. The undercover study sent black and white testers dressed in similar fashion into clubs at the same time and found that at fifteen bars on Bourbon Street, the black testers were either charged more for drinks or harassed by doormen. For example at the Tropical Isle, the black tester was charged $8 for a Long Island Iced Tea while the white tester was charged only $6.75 by the same bar tender. In addition, many of the black testers were charged an admission fee to bars whereas the white colleagues were admitted for free. Some speculate that this phenomenon occurred because clubs and bars did not want to be considered “black establishments.” Reports such as these give physical evidence that supports studies such as Lee’s. The racial tension in New Orleans caused much frustration among the African-American community. When Hurricane Katrina hit, the community was poised to voice these frustrations and did so through the creation of stories. 34 Rumor In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, rumors caused outbreaks of violence, looting, and panic throughout the city. Many believed that the levees had not simply broken, but had been blown up on purpose in order to sacrifice the lower income black neighborhoods and save the wealthy white neighborhoods. Parents stood in the middle of Canal Street encouraging their children to ransack businesses in order to “show them what it feels like to have your shit destroyed.” People were furious at the local government for having destroyed their homes and were furious that they had been ignored for so long. One woman who fumed on Canal Street described her perception of the way things were handled: “I heard the explosion myself about 5:30 this mornin’. They think they’re savin’ all of those rich folks up there. They just leavin’ us to fend for ourselves. They don’t care ‘bout us.” Rumors of sabotage such as these have a rich history in New Orleans. In 1965 Hurricane “Betsy was followed within days by wide spread rumors that Mayor Schiro had ordered floodwater pumped out of his own well-to-do subdivision, Lake Vista, and into the Ninth Ward” (Remnick 2005). As David Cohen told one reporter: “That theory is why older people in the Ninth Ward still keep hatchets in their attics. They remember what it was like to be trapped, with the water rising and no way to get to the roof” (Remnick 2005). Most New Orleans residents are willing to share a story about friends or relatives that experienced Hurricane Betsy in 1965. The account of intentional sabotage has been passed from generation to generation: “well my grandmother she stayed in the Lower 35 Ninth Ward, and when Hurricane Betsy had been over twenty years ago that’s when they first broke the levees and you know flooded all of the Lower Ninth Ward and they had to move everything from there and everything” (Interview: N003) Yet, the only disaster that shows any record of breeching levees on purpose was the great Mississippi flood of 1927. So, why do these stories of such deliberate sabotage exist? Rumors about racial conflict and oppression began as early as the slave era when early American slaves believed that they were being brought to the New World because their owners were cannibals that wanted to eat them (Turner 1993). During the 1980s, poor blacks often talked of “The Plan,” a secret scheme put into place by the “white power structure” in order remove blacks from Washington D.C. (Remnick 2005). According to Patricia Turner, rumors and conspiracy theories tend to appear in larger numbers during times of heightened racial conflict. During the 1960s, the federal authorities set up rumor hotlines and clinics in order to “combat the proverbial grapevine, on which stories about acts of violence, both incidental and conspiratorial, abounded” (Turner 1993: 2). Though the clinics and hotlines were shut down after the racial conflict of the 1960s dwindled, stories about the hostility between racial groups still circulate among African-Americans. For example, in 1990 a cigarette company called R.J Reynolds wanted to start a marketing campaign for a cigarette called ‘Uptown.’ The target demographic for this company was young African-Americans. Thus, adds began to appear on billboards in primarily African-American neighborhoods and in magazines such as Ebony, Jet, and Essence that were read primarily by blacks. The NAACP was outraged that a company would deliberately target a racial group and opposed the campaign vehemently. R.J. Reynolds abandoned their marketing strategy, but it was not long before rumors started to 36 spread about the company having ties to the Ku Klux Klan. Yet the truth of the matter is that R.J. Reynolds has always been a large supporter of the black community, donating money to academic funds specifically for African-Americans (Turner 1997). So, the question still remains: Why do rumors such as these persist? In their research about rumors surrounding public health in Cameroon, FeldmanSavelsberg, Ndonko, and Yang found that “reproductive insecurity is reinforced by collective memories1 of past threats, most particularly ‘the time of troubles’ surrounding Cameroon’s independence struggle. Memory of the troubles becomes a core symbol that organizes thought and serves as a short-cut, connecting different domains and historical periods, serving as a convenient explanation for the current state of affairs” (FeldmanSavelsberg et al. 2005: 153). Since the earliest colonial presence in Cameroon, the Bamiléké people have used rumor and collective memory as an important form of communication surrounding political disruptions. However, throughout the fight to maintain their ethnicity and way of life, one memory stands out from the rest: “Bamiléké women consistently invoke collective memories of the ‘time of troubles,’ a guerrilla war involving a radical nationalist anti-colonial movement, as a model explaining the present” (Savelsberg et al. 2005: 143). Just as Bamiléké people form rumors about government organizations deliberately sterilizing them in order to communicate their insecurities, people in New Orleans have formed rumors about sabotaging the levee system in order to communicate their distrust in governing authorities. Among the African-American population of New Orleans, the prominent memory of sabotage is during Hurricane Betsy in 1965, yet the only recorded intentional blowing 1 Collective memory is defined here as a term that separates notion from individual memory. Collective memory is created, shared, constructed, and passed on by a community or society. 37 of the levees was during the 1927 Great Mississippi flood. And even then, the areas that were flooded were primarily white lower-class areas. “So the first time they broke the levees [in 1965] they just blew them up. But this time you know, it was a question of did they intentionally blow the levees? Well, of course they did. But it was more a construction thing. You know, like did they loosen the screws? Or did they not build it back right?” (Interview N003) Have these memories of sabotage been reworked in order to convey a sense of distrust throughout the African-American community? As Ralph L. Rosnow and Gary Alan Fine demonstrate in their book Rumor and Gossip, rumors tend to appear more prevalently around situations of stress and ambiguity. Looking at the 2004 Quality of Life Survey conducted by the University of New Orleans in Orleans and Jefferson Parishes (one year before Katrina hit) researchers found that for the first time since 1997, voters in New Orleans were becoming increasingly negative about their perception of the quality of life in their city. Specifically, the perceived quality of the police department declined, prospects for employment decreased, and residents heard an increased incidence of gunfire in their neighborhoods. What is more, “the increasing concern about crime and safety has occurred disproportionately in the black community” (2004 Quality of Life Survey: 1). The African-American community was already disgruntled when the stories of the club murder hit the newsstands. The incident served as a catalyst in the black community and when Hurricane Katrina hit the feelings of oppression and racism were compounded by cutting off all reliable communication and information sources. People were left with only one way to communicate: word of mouth. 38 Having no access to information, we often relied on the stories of those walking up and down Canal Street. It was the rumor of even more water moving into our area that spurred us into frantically trying to find a way out of the city. Often, someone would come running into the lobby of the hotel with a fantastical story about more water rushing through the streets. People would begin to panic again, some would move upstairs for a few hours. Then, things would calm until the next person came into the lobby with a different story. We spent much of our time tracking down National Guard to verify a rumor that we had heard on the street. Though most of what we heard ended up being exaggeration or not true at all, it was the occasional fact in the midst of the rumor that allowed us to utilize our resources. Yet human nature always has a way of creating stories to help understand that which does not seem fair. As Allport and Postman found in their 1947 study, Many people have a need to answer the question “why me?” One of the conversations that has stuck out the most from my experience in New Orleans was with a man in his mid-sixties who had come to the Fairmont Hotel because he was unable to get out of the city in time after evacuating his bed and breakfast. In an effort to comfort a young girl on vacation, he told her about the different crises he had lived through: military coups in South America, being taken as a hostage in Europe, and now Hurricane Katrina. After finishing his story, the girl looked at him and asked: “Have you ever wondered why all of these horrible things have happened to you?” And he replied: “Sweetie, because I’m human. And they’re not horrible, they’re educational.” However, most humans are like the girl; they need an explanation for the things that happen to them. They need the ability to answer the question “Why me?” 39 A community that has repeatedly suffered extensive flood damage is no different. They need an explanation: “Quite apart from the pressure of particular emotions, we continually seek to extract meaning from our environment…we want to know why, how, and wherefore of the world that surrounds us. Our minds protest against chaos. From childhood we are asking why, why?” (Allport and Postman 1947: 503). We as humans always have a need to blame something for our losses. And because it is easier to affix blame to an entity like another race or the government, rather than a complicated system, people create stories that make the blame valid. “Every collectivity and social group has its preferred, virtually institutionalized scapegoats” (Kapferer 1990: 91). The communities on the East side of New Orleans are not willing to accept the fact that their homes are repeatedly flooded, their families displaced, and their belongings are ruined without affixing blame to something. One man that we passed asked us: “Do you see this shit? There was no water here yesterday and now water everywhere. You explain that to me. You explain to me why yesterday my house was fine and today I have nothing. You try to tell me they didn’t do this on purpose. That’s why we take this stuff: see how it is to have your shit destroyed. Shit, they don’t need this stuff. Insurance cover it. We need this stuff. We ain’t got nothin’ now.” And as Andrew Baker told the Times Picayne, “God didn’t play a part in this. They always do that. They flood the Lower 9” (Young 2005). 40 The Disaster Itself The problem with writing a paper such as this on a recent event is the lack of reliable information. There has been almost nothing released about the demographic of the people who were trapped in the city by the hurricane. However, drawing from observations while riding out the storm, it seemed that those who were unable to evacuate the city were those who did not own their own means of transportation. Because the only means of evacuating was by car, those who could not afford one or were visiting the city like my family, Rita, and I could not leave. This leads me to believe that those who were trapped were in the lower income bracket, often living below the poverty line. Though there is little proof that the majority of people trapped by the hurricane were AfricanAmerican, most of the people who we talked with and who passed us on the streets were black. As Rita said in her interview, “first, many people did not have cars to get out. If they did have a car, some did not have money to put gas in it. Or there were people like myself, who were visiting, that they had a way out arranged and it fell through…the only white person I distinctly remember seeing stuck at the Superdome looked like a crack addict.” Yet, as shown in Table 2, the vital statistics of all bodies at St. Gabriel Morgue points to remarkable evidence. Of the 910 victims sent to the morgue from the greater New Orleans area 815 were identified. Of those 815 bodies, 420 (52%) were AfricanAmerican, 326 (40%) were Caucasian, 37 (4%) were unknown, and 26 (>3%) were listed as Hispanic, Native American or Other. 41 Table 2: Vital Statistics of All Bodies at St. Gabriel Morgue New Orleans, Louisiana Gender Unkown Male Female Total Number 1 407 407 815 Percent 0% 50% 50% n/a 37 420 6 326 17 4 5 815 4% 52% 1% 40% 2% >1% >1% n/a Race Unkown African American Asian Pacific Causcasian Hispanic Native American Other Total Source: Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals http://www.dhh.state.la.us The statistics show that the percentage of African-American victims and Caucasian victims were about the same. However, we must remember that the population of New Orleans was around 28% white when the hurricane hit. This means that the rate of death among the white population was much higher than the rate of death among any other racial group. These statistics demonstrate that the death and destruction caused by the storm showed no discrimination. “‘The fascinating thing is that it’s so spread out,” Joachim Singelmann, director of the Louisiana Population Data Center at Louisiana State University. ‘It’s not just the Lower 9th Ward and New Orleans East, which everybody has heard about. It’s across the board, including some well-to-do neighborhoods’” (Riccardi et al. 2005). The damage caused by the storm was also spread across race and class lines. As shown in Figures 1 and 2, there were five levee breeches caused by the storm surge 42 during Hurricane Katrina. The largest breech was located at the 17th Street canal. The breech virtually wiped out the Lakeview neighborhood: a primarily white upper-class area with homes valued at hundreds of thousands of dollars (see Figures 3 and 4). “Lakeview, a predominately white neighborhood that contains mansions valued at more than $1 million in addition to crowded streets studded with modest bungalows, fronts the lake and is adjacent to the 17th Street canal. When the levee collapsed, the neighborhood was destroyed. The only neighborhood with comparable destruction, the Lower 9th Ward, sits on higher ground but was unluckily flanked by two broken levees” (The Los Angeles Times: December 2005). The breaks in the Bywater levee at the 9th Ward and the Industrial canal caused water to rush into the Lower Ninth Ward, Holy Cross, and other neighborhoods on the Eastern side of New Orleans. These neighborhoods were predominately black communities with a large population living below the official poverty line (see Figure 3 and Figure 5). According to the United States Census Bureau, 98.3% of the population living in the Lower Ninth Ward was African-American. An astonishing 36.4% of the people living in the ward were living below the poverty line. To put this in perspective, 25% of the population of the Lower Ninth Ward had a reported income of less than $10,000. This area was saturated with about twenty feet of water as was the Lakeview area. Lakeview is a neighborhood where 94% of the population was Caucasian. The average household income was reported to be $63,984, over $20,000 higher than that reported by the rest of the city of New Orleans in the most recent census data released in the year 2000. And, only 4.9% of the Lakeview population was living below the poverty line. 43 The same disparities and statistics ring true for areas such as St. Claude and the Lake Catherine neighborhood. St Claude was 90.5% African-American with 39% of its population living below the poverty line. In contrast, the Lake Catherine neighborhood in Eastern New Orleans was 94.3% white with 5.1% of the population being AfricanAmerican. And, only 10.7% of the population was reported as living below the official poverty line. The segregation and disparity in economic status in New Orleans is glaring. The figures provided in Appendix A provide a visual pattern to the racial segregation and the link between poverty and race. Yet, in Figure 1, it is clear that the extent of the flooding caused by the hurricane affected areas all over the city of New Orleans. The areas in blue represent sections of the city that were flooded with fourteen to nineteen feet of water. Using Figure 6, we see the correlation between the elevation of a neighborhood and the amount of water found within it. Those areas with the lowest elevations collected the largest amount of water. For example, the area directly east of the 17th Street canal has an elevation of up to four feet below sea level and collected up to twenty feet of water. The areas with elevations above sea level tended to collect only about three to five feet of water. Comparing Figures 1 and 3, we see that there is actually no correlation between the extent of water in a neighborhood and the level of poverty in the neighborhood. There is an extremely wide range of economic levels among neighborhoods that were affected in a catastrophic manner, meaning that areas such as the Lower Ninth Ward flooded to the same degree as areas such as the affluent Lakeview neighborhood. The same can be 44 said for race. There is no apparent correlation between the amount of water that flooded a neighborhood and is racial demographic. The actual disparity associated with this specific disaster was means of evacuation. If an individual did not own a car by Saturday afternoon, there was absolutely no way out of the city. Thus, the majority of people who were trapped by the storm were those who fell into the lower income levels of society and had no access to transportation. And as I have previously asserted, poverty is very closely associated with race in the city of New Orleans. Therefore, those people trapped in the city were primarily AfricanAmericans in the lower-class income bracket. Because the elite white population had already demonstrated how they were able to use their power when the levee was intentionally blown in 1927, it becomes easy for an outsider to understand why and how the African-American population would feel singled out by the events surrounding Hurricane Katrina. Conclusion In researching a rumor such as the intentional sabotage of the levee system in New Orleans, one can not help but ask the inevitable: Were the levees actually blown up on purpose? To date, there is no conclusive evidence to answer the question in one way or another. However, in investigating stories such as these, it does not matter whether or not the levees were blown on purpose. It has become a reality for those who tell the story. The history of New Orleans is rich with racism that is still made apparent by the extremely segregated residential districts found throughout. The severe instance of poverty found in the African-American population meant that many did not have the 45 financial means to evacuate the city. The lack of access to transportation caused a human tragedy in Louisiana. Those who did not own a car or have the financial means to fuel it, were trapped by the hurricane. Ergo, the complicated demographic of the city left primarily African-Americans living below the poverty line in the path of the storm. New Orleans evokes a feeling that one cannot quite put a finger on: it is mysterious and romantic, yet, underneath the dreamy mask of the Old South, the city pulsates with tension. This tension becomes apparent in the formation of stories by the African-American population. But the story is complicated by the statistics released so far. All kinds of people, from the rich to the poor and the black to the white, suffered loss and ruin. Flood damage, death, and destruction showed no disparity between class and gender. So, we must ask the question, why do stories of intentional sabotage exist among the African-American community in New Orleans? We tell stories to each other in order to explain the unexplainable. Things that we cannot prove, but know are true, are turned into stories that we pass from generation to generation and person to person in order to convey information that would not be heard otherwise. In New Orleans, the memories of injustice, classism, and racism make the idea of intentionally blowing up the levees completely reasonable. “Without all the facts [from the National Science Foundation] it would be easy to think, ‘those bastards did what they did in 1927.’ I think it’s very rational” (Young 2005: 2). By nature, people feel the need to affix blame to tragedy. The African-American community has a need to blame something for the continued destruction caused by flooding, and the historical racial tension within the city is the perfect vehicle. Years of suppression and segregation provide the foundation from which to form stories of deliberate sabotage. “African- 46 Americans in the Lower 9th Ward have been disenfranchised by those in power…I think we are really talking about a fairly commonplace human phenomenon, not necessarily an African-American phenomenon” (Young 2005: 4). Rumors are created as a form of explanation when something is out of place or disrupted. Specifically in the instance of New Orleans in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, rumors ran rampant in the absence of reliable information. Memories and stories that already existed were compounded by the lack of communication by valid and authoritative sources. Due to the amount of stress the community was put under, people had no way of knowing what was actually happening around them. They felt the need to explain their situation according to their immediate surroundings. “‘People need an explanation for what’s happened,’ Turner said. ‘And an explanation is a story with a beginning, a middle, and an end.’ And in the history of Louisiana, African-Americans have been given plenty of reason to distrust white authority, she said” (Young 2005: 4). The rumors and stories surrounding the devastation of Hurricane Katrina provide sociologists with a wealth of information that is crucial to understand the social climate within the city. We can do all the research we want, but in reality the perceptions of the people are told in the stories that they pass amongst themselves. In the broadest context, it does not matter whether or not they are true. What matters is that the social climate in New Orleans was such that the African-American population felt the need to make these stories true. 47 Works Cited Allport, Gordon W. and Postman, Leo 1946 An Analysis of Rumor. The Public Opinion Quarterly. 10(4): 501 -517. Barry, John M. 1997 Rising Tide: The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and How It Changed America. Simon and Schuster Inc: New York, New York. Burawoy, Michael 1998 The extended case method. Sociological Theory. 16: 4 – 33. Clark, Lee and Short, James F. 1993 Social Organization and risk: Some current controversies. Annual review of Sociology 19: 159 - 176 DeParle, Jason 2005 Broken Levees, Unbroken Barriers. The New York Times. September 4: Sec 4, Pg. 1. Dirks, Robert 1980 Social responses During Severe Food Shortages and Famine. Current Anthropology 21(1): 21 – 44. Federal Emergency Management Agency 2005 Guideline to disaster. www.fema.gov Accessed October 28, 2005. Feldman-Savelsberg, Pamela an Ndonko, Flavien T. and Yang, Song 2005 How Rumor Begets Rumor: Collective Memory, Ethnic Conflict, and Reproductive Rumors in Cameroon In Rumor Mills: The Social Impact of Rumor and Legend. Transaction Publishers: New Brunswick and London. Fine, Gary Alan and Rosnow, Ralph L. 1976 Rumor and Gossip: The Social Psychology of Hearsay. Elsevier Press: New York, Oxford, and Amsterdam. Greater New Orleans Community Data Center 2000 [2005] http://www.gnocdc.org/ accessed November 16, 2005 Gold, Scott 2005 Big Easy Is Uneasy After Death of Black Clubgoer. The Los Angeles Times. May, 20: A1. Hirsch, Arnold R. 1992 Creole New Orleans: Race and Americanization. Louisiana State University Press: Baton Rouge and London. 48 Kapferer, Jean Noel 1990 Rumor: Uses Interpretations and Images. Transaction Publishers: New Brunswick. Kiter-Edwards, Margie 1998 An Interdisciplinary Perspective on Disasters and Stress: The Promise of an Ecological Framework In Sociological Forum. 12(1) 115 – 132. Klinenberg, Eric 2002 Heat Wave: The Social Autopsy of Chicago. The University of Chicago Press: Chicago and London. Lee, Silas 2003 A Haunted City? The Social and Economic Status of African Americans and Whites in New Orleans. Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals 2006 Vital Statistics of All Bodies at St. Gabriel Morgue. http://www.dhh.louisiana.gov/offices/publications/pubs145/Deceased%20Victims_1209_information.pdf accessed March 2, 2006 Louisiana Geographic Information Center 2005 http//lagic.lsu.edu accessed November 16, 2005 Oliver-Smith, Anthony 1996 Anthropological Research on Hazards and Disasters. Annual Review of Anthropology. 25: 303- 328. Remnick, David 2005 High Water; Letter From Louisiana. The New Yorker. October 3, 81(30): 48. Riccardi, Nicholas, Smith, Doug, and Zucchino, David 2005 Katrina Killed Across Class Lines. The Los Angeles Times. December 18. Shumsky, Larry Neil 1998 Encyclopedia of Urban America: The Cities and Suburbs. ABC-CLIO Inc: California. 2:525 -528. Spain, Daphne 1979 Race Relations and Residential Segregation in New Orleans: Two Centuries of Paradox. In Race and Residence in American Cities. 441:82 – 96. 49 Turner, Patricia A. 1993 I Heard it Through the Grapevine: Rumor in African-American cultures. University of California Press: Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London. United States Census Bureau 2000 [2005] American Fact Finder http://factfinder.census.gov/home/saff/main.html?_lang=en accessed October 28, 2005. University of New Orleans 2002 Quality of Life Survey, 2002. New Orleans, Louisiana: Survey Research Center. University of New Orleans 2003 Quality of Life Survey, 2004. New Orleans, Louisiana: Survey Research Center. Warheit, George J. 1988 Disasters and their mental health consequences: Findings and future trends. Mental Health Response to Mass Emergencies: Theory and Practice. New York: Brunner, Mazel: 3 – 21. Young, Tara 2005 Rumor of Levee Dynamite Persists. The Times-Picayune. December 12: A4. 50 Appendix A Levee Breech Source: Louisiana Geographic Information Center (LAGC) – http//lagic.lsu.edu Figure 1 Flood Depth Estimates in New Orleans August 27, 2005 53 Source: Louisiana Geographic Information Center (LAGC) – http//lagic.lsu.edu Figure 2 Source: Louisiana Geographic Information Center (LAGC) – http//lagic.lsu.edu Figure 3 2 2 “People living below the poverty line includes all individuals whose family has income that is lower than twice the poverty threshold for the family size. Because poverty thresholds are generally considered to be flawed and have not been appropriately adjusted since they were created in 1964, twice the poverty threshold is commonly used as a rough proxy for a living wage” (Louisiana Geographic Information Center (LAGC) – http/lagic.lsu.edu) 55 Source: Louisiana Geographic Information Center (LAGC) – http//lagic.lsu.edu Figure 4 Source: Louisiana Geographic Information Center (LAGC) – http//lagic.lsu.edu Figure 5 Source: Louisiana Geographic Information Center (LAGC) – http//lagic.lsu.edu Figure 6