CELS News Article - College of the Environment and Life Sciences

advertisement

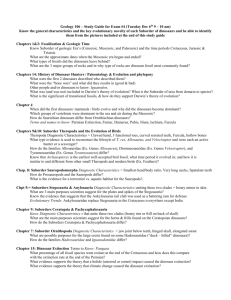

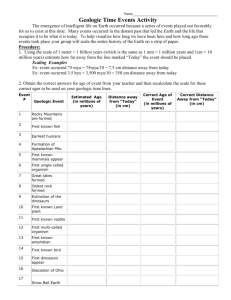

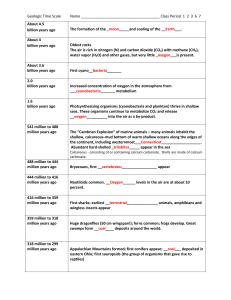

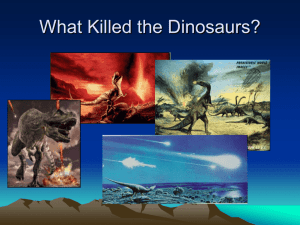

CELS News Article Fall, 2006 Faculty Spotlight: Faculty Spotlight on David E. Fastovsky, URI’s “dinosaur hunter” By: Rudi Hempe, CELS News Editor and Reporter ---------------------------------------------------------Vacationing in Mexico—ah, the leisurely tropical life, gorgeous beaches, exotic foods and fascinating historic sites. Dr. David E. Fastovsky recently returned from a rather “historic” site in Mexico but he reports it was hot and buggy and there wasn’t a beach in sight—not the typical vacation report one would expect but then again he wasn’t there on vacation. Rather he was probing through a site of ancient volcanic deposits that millions of years ago trapped dinosaur bones--duckbills and theropods. The site is near Tiquicheo, a small town in the state of Michoacan which lies southwest of Mexico City. Michoacan is an active volcanic region (a new volcano, Paricutin, emerged in 1943 and grew slowly for nine years) and three years ago, Dr. Mouloud Benammi, a geologist in the Institute of Geophysics at the National University of Mexico (UNAM) started exploring a site where volcano deposits (more water and ash than lava) had trapped dinosaurs of the Cretaceous Period 84 million years ago. Benammi wrote a paper describing the bones—several of which indicated dinosaurs of 20 or more feet in length—and Fastovsky and he chatted about the locality during Fastovsky’s Fulbright Fellowship-supported sabbatical year in Mexico. Fastovsky, who had worked previously on several other dinosaur localities in Mexico, visited the site with Benammi for a few days. They didn’t find any bones on that visit but the place intrigued him. “It was a very difficult,” says Fastovsky referring to the harsh terrain and lack of good maps, “and I was thinking, ‘Do I really want to do this?’” After returning from the field to Mexico City, Fastovsky and his Mexican colleagues wrote a proposal to the National Geographic Society asking for funding for further exploration of the site. In the mean time, Benammi found more bones at the site. National Geographic approved the modest grant and earlier this summer, they worked the site with several students from UNAM. “I didn’t look for dinosaurs on this visit,” says Fastovsky who has taught a very popular course on dinosaurs for the last 20 years and is a co-author of a book, The Evolution and Extinction of the Dinosaurs. “I’m focusing on what the environment was like back then,” he adds, noting that “the rocks are the key.” That requires looking at the rocks closely, trying to determine the type of volcanism that trapped the dinosaur bones. Ancient soils were deposited between volcanic flows, says Fastovsky indicating that there were quiescent periods between terrifying volcanic episodes “although that story could change” with further study. He plans to return to the site next March. Fastovsky became interested in dinosaurs when he was a kid and picked up one of the “All About” books. He got his Bachelor’s degree in biology at Reed College and then went to the University of California-Berkeley for his Masters in paleontology after doing research on fossil turtles. He received his PhD from the University of Wisconsin-Madison doing research on an environment that was rich in dinosaurs in eastern Montana. An outgrowth of his thesis work has been his long-term contribution to what is known of the extinction of the dinosaurs at the Cretaceous-Tertiary (K-T) boundary. Over the past 20 years, Fastovsky and his colleagues have been able to show that where they are found at the boundary, the extinction of North American dinosaurs was “geologically instantaneous.” By that he means that the extinction encompassed “time-scales of tens of thousands of years (or less.)” An abrupt extinction is concordant with a catastrophic agent of extinction. The K-T boundary (Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary) reveals an unusual thin layer of clay that contains high amounts of the rare element, iridium, which is found in meteorites. The spike in the iridium deposit can be explained by either a massive collision with a meteorite, as asteroid or a comet or the advent of an unusual amount of volcanism, whereby iridium, deposited by meteorites on the earth when it was still molten, could have been ejected with the magma. The K-T boundary coincides with the massive extinction of many forms of life including the dinosaurs. A widely accepted theory is that the extinction was caused by a chondritic asteroid about 10 km in diameter, that struck the earth 65 million years ago just off the northwest tip of what is today the Yucatan Peninsula. The impact, equivalent to millions of tons of TNT, would have destroyed a vast area, sent out a shock wave resulting in fires, caused tidal waves and triggered earthquakes and volcanic activity. A cloud of debris would have been lifted into the atmosphere, blocking sunlight and causing a decrease in global temperatures. Other theories suggest there was a subsequent rise in global temperatures caused by the large amount of carbon dioxide that resulted from the widespread fires that destroyed vast amounts of vegetation. On land, herbivores and carnivores died out as their food resources disappeared. Some smaller creatures like birds and mammals would have survived by scavenging. Fastovsky and his colleagues demonstrated that creatures in aquatic environments were more likely to survive than those living on land. They suggested that this was because these creatures were more likely to be detritus feeders – animals that didn’t require fresh plant matter – or meat. Figuring out what happened so many million of years ago is not easy. The rocks that contain clues of the distant past are only exposed in certain locations and sites where dinosaur fossils are found are even rarer. Back at the Mexico site, much work remains to be done, says Fastovsky. All the published maps in Mexico, he says, suggested that the site was young but the presence of dinosaurs shows that it is much older. “Clearly it needed to be looked at,” he said adding that the plan is to integrate the data into the tectonic history of Mexico. Once the National Geographic Society grant runs out, Fastovsky hopes he can interest the National Science Foundation to approve a more long-term grant to continue the work. “You never know what you are going to find,” he says.