the handbook - Saskatchewan Archaeological Society

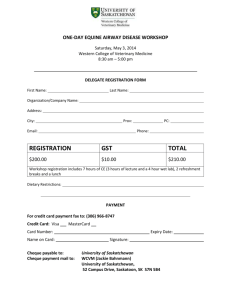

advertisement