ASIST Proceedings Template

advertisement

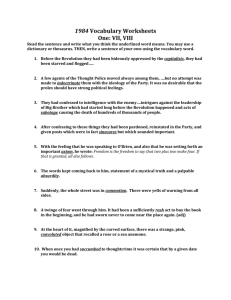

Issues in the Development of a Thesaurus for Patients’ Chief Complaints in the Emergency Department Stephanie W. Haas School of Information and Library Science, CB#3360, 100 Manning Hall, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3360. Email: stephani@ils.unc.edu Debbie A. Travers Department of Emergency Medicine, School of Medicine, CB#7594, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC. 27599-7594. Email: dtravers@med.unc.edu When a patient visits the Emergency Department (ED), the reason the patient is seeking care is recorded as the Chief Complaint (CC). Beyond its role in the patient’s care, there is interest in the CC for secondary uses. Clinicians and epidemiologists can use CC for research. ED clinicians and administrators incorporate CC data into quality monitoring and improvement efforts. Public health officials can use it as data for health surveillance. But there is no controlled vocabulary for recording CC, or standard for a CC component in the patient record. Travers (2003) completed a crucial first step toward the creation of a thesaurus for CC by analyzing a corpus of CCs to determine the nature of the language used by triage nurses, and the concepts that were expressed. Her analysis also illuminated many issues concerning the content and structure of a CC thesaurus that must be discussed before the thesaurus can be developed. Using Cimino’s 1998 article, “Desiderata for Controlled Medical Vocabularies in the Twenty-First Century”, as a framework, we discuss these issues and the resulting decisions that the thesaurus development team, along with other stakeholders, will encounter. Introduction When a patient visits the Emergency Department (ED), the triage nurse asks the reason the patient is seeking care. This information is recorded as the Chief Complaint (CC), and it influences many aspects of the ED visit, such as the speed with which the patient is seen, or any immediate treatment needed. The initial actions of the ED clinical team therefore depend on the CC. Beyond its role in the patient’s care, there is interest in the CC for secondary uses. Clinicians and epidemiologists can use CC for research. ED clinicians and administrators incorporate CC data into quality monitoring and improvement efforts. Public health officials can use it as data for health surveillance, both for bioterrorism surveillance and other kinds of problems, such as identifying potential SARS victims, or early identification of flu outbreaks. But the CC is not collected in a way that will readily support these uses; there is no controlled vocabulary for recording CC, or standard for a CC component in the patient record. In a survey of North Carolina and Seattle EDs, Travers et al. (2003) found that CC was collected in a variety of formats, including free text, locally developed or adapted term lists and commercially-provided lists. Without a standardized vocabulary, aggregating CC data requires immense human effort to collect all the CCs that express the same concept. Without this “translation” step, results are likely to be unreliable. There have been calls for a standardized CC vocabulary from many sources. Initial work by the Emergency Nurses Association (ENA) on an emergency nursing minimum data set was incorporated into a multi-disciplinary effort sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which led to the release of Data Elements for Emergency Departments (DEEDS) 1.0 in 1997 (Bradley, 1995 & 1996; NCIPC, 1997; Pollock et al., 1998). DEEDS data element 4.06 is “Chief Complaint”. Since no standard vocabulary exists for documentation of CC, the DEEDS and ENA leaders recommended evaluation and adaptation of established terminologies as a solution to the need for an ED CC controlled vocabulary. The shortcomings of existing CC data have been documented, and include lack of CCs in electronic form and CCs documented in a variety of formats (free text, locally developed lists, varying field lengths from 12-250 characters (Travers et al, 2003; Coben et al., 1996; Cline, 2000). In spite of the lack of a CC terminology, CC data are currently used for many public health, academic, and hospital-based surveillance applications. For example, ED CC data are a component of several regional bioterrorism surveillance systems, in which various techniques such as keyword searches and natural language processing (NLP) techniques (e.g., stemming) are used to identify certain CC terms indicative of potential biological agent exposure (Greenko, Mostashari, Fine & Layton, 2003; Ivanov, Wagner, Chapman & Olszewski, 2002). One reason for the interest in the CC for disease surveillance is that the CC is recorded at the start of the ED visit, and therefore has the potential to be available in a timelier manner than conventional disease-reporting methods. Researchers have shown that CC data can be used to detect disease outbreaks up to 2 weeks sooner than the conventional approach, which involves waiting for lab reports and final diagnoses to trigger reporting (Tsui et al., 2001; Teich et al., 2002). Given that the CC is already used as a source of data for surveillance and other secondary uses, improving the quality of CC data is of utmost importance. A CC thesaurus would represent the concepts, preferred terms, and synonyms needed to support a controlled vocabulary for CC. Developing a thesaurus is a significant undertaking that should involve a variety of stakeholders: ED clinicians, those interested in secondary uses of CC such as research or health surveillance, and professional and standards organizations whose approval and continuing support would be necessary for its widespread acceptance and use, as well as ongoing maintenance. Additional operational constraints arise from the busy ED environment. Triage nurses typically have only a couple of minutes to evaluate a patient’s condition. Any information system based on the thesaurus must allow nurses to enter an accurate CC quickly, and the CC must be informative to the other ED clinicians who base decisions about the patient’s initial care on the CC. Travers (2003) completed a crucial first step toward the creation of a thesaurus for CC by analyzing a corpus of CCs to determine the nature of the language used by triage nurses, and the concepts that were expressed. Her analysis also illuminated many issues concerning the content and structure of a CC thesaurus, that must be discussed before the thesaurus can be developed. Using Cimino’s 1998 article, “Desiderata for Controlled Medical Vocabularies in the Twenty-First Century”, as a framework, we discuss these issues and the resulting decisions that the thesaurus development team, along with other stakeholders, will encounter. Analysis of Chief Complaints We present a brief overview of Travers’ research here; details may be found in her dissertation and related papers (Travers, 2003; Travers & Bodenreider, 2002; Travers & Haas, 2003). She created a corpus of one year’s worth of CCs, collected from three southeastern EDs representing urban, rural and suburban academic medical centers. CCs were entered as free text at two of the sites. At the third site, nurses could use a vendor-developed controlled list of terms, enter the CC as free text, or both. The CC could be up to 30 characters at two of the sites, but was limited to 12 at the other. Travers developed the Emergency Medical Text Processor (EMT-P), a set of modules that cleans and normalizes text and extracts standardized terms. CC entries, like other kinds of unedited free text, are messy. Travers found a variety of abbreviations, truncations, misspellings, local expressions, coordinate structures, punctuation, and other interesting (and occasionally puzzling) characteristics. She then identified the concepts expressed in the cleaned CCs, and mapped them to concepts identified in the National Library of Medicine’s Unified Medical Language System Metathesaurus®. Her work accomplished several goals, including the development of a list of almost 4,000 concepts used by triage nurses in CCs, collection of groups of words, phrases, abbreviations and other expressions that nurses used to name each concept, and identification of ED concepts that were not in the Metathesaurus®. These missing concepts are not included in any of the UMLS component vocabularies, and would need to be added in order to provide complete coverage of the ED CC domain. This paper focuses on a set of findings from Travers’ analysis of CC terms that raise specific issues for the design and development of a CC thesaurus. In the next section, we summarize Cimino’s (1998) desiderata for controlled medical vocabularies, which provide a useful framework in which to consider these findings. In the following sections, we discuss each issue and their implications for the CC thesaurus. Desiderata We can group the most pertinent of Cimino’s desiderata into those relating to the content, structure, and administration of the thesaurus. Content First and foremost, the thesaurus should provide complete coverage of all the concepts in the domain. In other words, users of the vocabulary should be able to express whatever they need to. This implies a process of laying out the scope of the domain, and then enumerating the concepts therein. Cimino urges that a controlled vocabulary be “concept oriented”. Concepts should be distinct from each other. Terms should refer to a single concept; not be overly vague, and not be ambiguous. Note that this does not rule out the inclusion of synonyms. A thesaurus can represent concepts and a preferred term for the concept, but also include other terms, phrases, abbreviations, etc. that refer to the same concept. Finally, there must be some way to recognize gaps in the coverage of the thesaurus, and define procedures for filling them. Gaps may occur because of discoveries in the discipline, recognition of distinctions that had not been made before, or simple omissions at the time of original development. Structure Decisions about the structure of the thesaurus are closely related to decisions about its scope and content. Cimino recommends that a controlled vocabulary provide varying levels of granularity in concepts. A very specific concept may be more informative, but often, especially in the early stages in medical care such as triage, only a more general concept can be used. For example, the CC may be rash, and only later in the visit can the specific type or cause of the rash be determined. A related question is what the desired “unit” of concept is. If only simple “single-element” units are included, then there must be some rules for combining them to create more complex concepts. Cimino illustrates this with the example of bone fractures. One could try to enumerate all the possible combinations of types of fractures and bone names, or one could include the fracture types and the bones, and specify post-coordination rules that will eliminate the possibility of producing nonsensical combinations. Usage rules could be expanded to include representation of the context in which a concept can be used, or relationships with other data fields. This is directly related to the scope of the thesaurus itself, and how it articulates with those of related domains. Administration Two of the desiderata concern the creation of a controlled vocabulary. First, what is the purpose for which it will be used? Cimino urges that vocabularies be designed to support many purposes, rather than just one. This implies that designers should know how the thesaurus will be used. The next question is whether a new controlled vocabulary is actually needed, or whether an existing one can be used, perhaps with minor adaptations. Uncontrolled additions to a vocabulary can lead to redundancy and muddled concepts. On the other hand, proliferation of many specialpurpose vocabularies complicates data sharing and merging. Finally, it is important to consider who is responsible for maintaining and updating the vocabulary. Buy-in by stakeholder organizations is important to foster use of the vocabulary, but shared responsibility, for maintenance, for example, can be difficult to co-ordinate. Findings for Thesaurus Development In this section, we use Cimino’s content, structure, and administration desiderata as a framework for discussing the implications of Travers’ findings for the design of the CC thesaurus. Travers also identified additional issues specific to the ED that are included in our discussion. Content of the Thesaurus Although the corpus from which Travers (2003) extracted CC concepts was large, it cannot be assumed that all concepts that triage nurses need to express were used in it. It is likely, however, that the most commonly-used concepts were found. The 564 most frequent CC entry types accounted for 50% of the entry tokens. There was general agreement among the three EDs from which the sample was drawn as to the most common concepts. The 4 most frequent CC concepts in the corpus (abdominal pain, chest pain, fever, and headache) accounted for 18% of the entry tokens. These same concepts were the 4 most frequent concepts found in the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) annual survey of EDs, where they accounted for about 20% of patient visits (McCaig & Burt, 2001, 2003; McCaig & Ly, 2002). EDs in different parts of the country, or those that serve different populations, may use additional terms for known concepts, and may also need additional concepts (although these are likely to be less common ones). For example, Travers found that each ED had a different coding scheme for describing special patient populations, such as unidentified patients, or those with major trauma or cardiopulmonary arrest. The controlled vocabulary must either provide a single standardized scheme, or the thesaurus must allow for easy addition of local variants. Although the latter approach would allow individual EDs to continue using their customary scheme, it has drawbacks for aggregating data across EDs. Given the expectations of encountering new concepts and new ways of expressing concepts, any interface based on the CC thesaurus must allow triage nurses to add additional free text entries to the CC when they feel that the existing vocabulary is insufficient. This is not necessarily bad news: these entries have a role to play in satisfying the next requirement. Since it is impossible to definitively identify all possible CC concepts, or anticipate new ones, effort should be focused on developing means for recognizing and incorporating new concepts into the thesaurus. The matching strategies that Travers used to map concepts found in the CCs to concepts in the UMLS Metathesaurus® can be the basis for regular monitoring to identify new concepts. Free text CCs that do not match any UMLS concept, or that are incorrectly matched, may be evidence of either a new or previously unseen concept, or a new or previously unseen way of expressing a known concept. These could signal the need to update the thesaurus. Mapping CC concepts to concepts in the UMLS helps fulfill Cimino’s requirement of concept orientation for the CC thesaurus. In addition, the mapping process highlighted several areas of concept definition that need investigation. Some common CC concepts were not found in the UMLS. For example, patients are frequently brought to the ED for clearance; to verify their medical stability before they are sent to a jail or substance abuse detoxification center. CCs such as jail clearance or detox clearance represent a function of the ED whose concepts are possible additions to the UMLS. Other CC concepts were closely related to concepts in the UMLS, but were not considered matches by the panel of experts who validated a sample of matches (Travers, 2003). These mismatches or partial matches often represent differences in perspective between EM clinicians and the medical vocabularies present in the UMLS. For example, the UMLS contains motor vehicle accident (MVA), which includes bicycles and motorcycles, but seems to be restricted to accidents on roads. EM clinicians need more specific concepts, such as motor vehicle crash (MVC), or motorcycle crash. The corpus included related CCs such as ped vs. car and bike vs. car, indicating collisions involving pedestrians or bicycles. In other cases, the UMLS contains multiple concepts, which, for the purposes of representing CCs, may be deemed by experts to be similar enough to be combined. For example, the UMLS includes both the concept shortness of breath, and the concept dyspnea. The phrase shortness of breath is also listed as a synonym for dyspnea. These examples of “missed synonymy” are often an artifact of merging multiple vocabularies (Hole & Srinivasan, 2000). The thesaurus development team will need to decide whether to merge similar concepts into a single concept. Other concepts also require consideration by domain experts. For example, the term congestion is ambiguous when seen in isolation away from the ED setting. In the validation study (Travers, 2003), one expert said that even though the usual assumption in the ED is that it refers to nasal congestion, the UMLS concept that was proposed as a match was broader, and could refer to nasal, pulmonary or hepatic congestion. These examples emphasize the importance of defining concepts in a specific clinical context, in this case, the ED. Analysis of the CC corpus revealed extensive use of synonyms, abbreviations, and truncations, especially for common concepts. For example, the most common concept, abdominal pain, had 7 synonyms. However, the analysis also highlighted the frequent misspellings of terms and abbreviations, for example, the 10 different ways that hemorrhoid was spelled. Should the thesaurus include illformed (but common) synonyms in addition to well-formed ones? Another way of framing the question is, should the thesaurus represent CC language the way it is used, or in its preferred form? Analysis of free-text CCs, as well as other types of clinical notes, will require recognition of these misspelled words. The EMT-P system currently contains modules that recognize and transform them to standard terms, but an argument could be made that including them in the thesaurus would make it more robust. This is a question of “division of labor” between the thesaurus itself and additional processing routines needed to support various applications. Structure of the Thesaurus Many of Travers’ findings concern the scope and structure of the thesaurus, but also have implications for the structure of the patient record. Co-morbidities are existing medical conditions that may be related to the patient’s CC or affect patient management. Common co-morbidities found in the CC corpus included patient currently pregnant and diabetes. These are not the reasons patients come to the ED; their visits are due to specific complaints such as labor pains or altered mental status. The thesaurus must include co-morbidities, but recording them in a separate field in the patient record may be more precise than combining them with the CC. When patients’ visits were associated with an injury, CCs in the corpus frequently included the method of injury (MOI), such as MVC/Neck Pain, or Alt MS/Fell (altered mental state, fell) Further, many CCs consisted only of a MOI, with no information about symptoms. The frequency with which MOI was used indicates that the thesaurus should include MOI concepts, but as with co-morbidities, perhaps they should be recorded in a separate field. This would also make extracting injury-related data for research and public health surveillance easier. Several types of modifiers and qualifiers were found in the CCs. Modifiers are words that alter the severity, location, or acuity of a CC (Chute and Elkin, 1997), such as right leg, or acute arm pain. Qualifiers qualify, or circumscribe, the meaning of a term, such as history of seizure. Cimino mentioned the choice between including only simple concepts which can then be combined as they are needed, or pre-coordinating them into complex concepts. The UMLS is inconsistent in this regard, since it is derived from the structures of its component vocabularies. For example, it includes left flank pain, but not left femur pain as concepts. One approach would be for the thesaurus to include the most common combinations, such as right leg, and allow post-coordination when triage nurses need to express less common combinations. (Note the advantage that the corpus-based approach to developing the thesaurus gives; frequency information is readily available.) The thesaurus would then need rules to prohibit ill-formed combinations, such as right rash. It might be possible to base at least some rules on the UMLS semantic types, such as allowing a description of laterality (right or left) to modify a body location, but not a sign or symptom. Other candidates for pre-coordination are frequently occurring conjoined CCs. For example nausea and vomiting frequently occurred together, and there is a UMLS concept that represents this combination. Other frequent combinations, such as fever and vomiting, might also be included as a pre-coordinated concept. This implies that in some cases, more than one CC can be included in a single field; we discuss the need for multiple fields below. Some allowable combinations of CCs may also be based on semantic types. For example, a common combination in the corpus was body part plus a lesion or injury type, such bump on head or finger laceration. Several kinds of expressions of time were found in the CCs. Temporal expressions represented duration of a complaint (for 3 weeks), the frequency with which a problem occurred (twice a day), and the time at which an event such as an injury or medical procedure took place (yesterday, June 4th). These expressions require more analysis to determine their structure and use in the CC. As with other qualifiers, rules for their combination with other CC terms are needed; for example leg injury every a.m. does not make sense. Numbers were used to express dates and times, but also other information such as temperatures, and visual acuity. As with temporal expressions, further analysis is needed to understand their structure and use. We have already mentioned that rules are needed for post-coordination of qualifiers and modifiers with CC concepts , and combining CCs. Other kinds of rules could express relationships between fields in the patient record. For example, MOI was frequently the only information in the CC. If instead it is recorded in its own field, should there be a rule also requiring an entry in the CC field? Another example concerns identifying an entry such as temp 100.7 as a synonym for fever. It may depend on other information in the record, such as the time of day, and the age of the patient. These sorts of rules go beyond specifying well-formed post-coordinations into the realm of inference. The final structural issue we present concerns the number of CC fields the patient record should contain. Our survey of EDs (Travers et al., 2003) found that most electronic records allowed only one CC field, but some allowed 2, 3 or more. The size of the fields ranged from 12 characters to “paragraphs”. Travers found that many entries in the corpus included multiple CC concepts, such as abdominal pain & headache & fever, which contains three separate concepts. This raises the issue of whether a standardized patient record should have more than one CC field. If so, what guidelines should be specified for their use? For example, one field could be designated the primary field, which should always have an entry, while the other(s) could be secondary; and used only when more than one CC is needed. Administration of the Thesaurus Cimino urged that a controlled vocabulary be designed to support many purposes. The primary purpose of the CC thesaurus is to support a controlled vocabulary for recording CC in ED patient records. A thesaurus allows the development of a concept-oriented vocabulary, and the designation of preferred terms and synonyms (possibly including ill-formed synonyms). A crucial element of support for this primary purpose lies in the design of user interfaces that will help triage nurses select and/or enter informative, unambiguous terms in the hectic environment of the ED. There are many possibilities. Nurses could pick one or more CCs from a list of preferred terms. The list could be sorted according to frequency of use, organized by type of problem, body part or system, or some other scheme. Another approach would allow nurses to start to enter free text CCs, and be prompted with suggested completions drawn from the preferred term list, from which they would select the most accurate one. Or, free text entries could be converted to controlled terms by the information system in the background, using EMT-P. Research is needed to determine the most appropriate interface designs, but the thesaurus should not limit the possibilities. The thesaurus will also support a variety of secondary analyses of CC, which could be used for bioterrorism and other types of health surveillance, research, quality improvement efforts of ED care, etc. As long as there is no controlled vocabulary for CC, this information is exceedingly difficult and time-consuming to use. Another possible use for the thesaurus is to support processing of clinical notes, such as nurse and physician notes, in the ED. Applications could include translating concepts used in the notes into a standardized vocabulary, indexing, searching, or summarization. This assumes that there is substantial similarity in the concepts and language used in clinical notes and the CC, an assumption which needs to be tested. Since CC and ED clinical notes are both within the domain of emergency medicine, there is likely to be abundant overlap of concepts, but the structure of the language may differ. The limited length of many CC fields, along with the fast pace of triage, encourages (or forces) substantial use of abbreviations, acronyms, and truncations. Space limitations may not be as severe for notes, on the other hand, the time constraints may have the same effect. Stetson, Johnson, Scotch and Hripcsak (2002) did find differences in the language used by hospital clinicians in various types of notes and reports. By mapping the CC concepts to UMLS concepts, Travers was able to provide some information about whether there is an existing medical vocabulary that could be adapted for the CC. We have already mentioned that there are some concepts missing from the UMLS; any vocabulary would need to have these added. The two vocabularies that contained the most concepts in the CC corpus were Clinical Terms Version 3 (also known as the Read Codes, England, National Health Service Centre for Coding and Classification, 1999), which covered 65% of the CC concepts, and Systematized Nomenclature of Human and Veterinary Medicine: SNOMED International, Version 3.5 (Cote, Roger A., editor, College of American Pathologists, 1998), which covered 50% of the CC concepts. These two vocabularies have recently been merged into SNOMED CT (College of American Pathologists, 2002), which is being incorporated into the UMLS Metathesaurus®. This seems to be a good candidate for consideration. The last administrative requirement from Cimino that we mention here concerns who takes responsibility for distributing and maintaining the thesaurus. This is a question that must be resolved by the various organizations that have an interest in medical vocabularies, and will also depend on the decision to adapt an existing vocabulary or create a new one. Conclusions and Future Work Cimino’s 1998 “Desiderata” laid out requirements for a sound controlled vocabulary or thesaurus on a general level, applicable to any medical vocabulary. Travers (2003), and Travers & Haas (2003) reported on research that gathered and analyzed a large portion of the information needed to build a thesaurus that would satisfy these requirements, including concept orientation, recognition of synonyms, and means of identifying needed updates and modifications of the thesaurus over time. We have placed others of Cimino’s requirements in the specific context of the CC, framing questions relating to scope and coverage (e.g., pre- or post-coordination of concepts, and merging similar concepts), and the structure of the thesaurus (e.g., inclusion and use of MOI and qualifiers and modifiers). Further work is needed to clarify these issues and develop guidelines for the development of the CC thesaurus. First, we will expand the comparison of CC terms and concepts with existing vocabularies to determine whether any can be easily adapted for our needs. We will explore both the coverage of the vocabularies, and policy and licensing decisions as to their availability. The second step is to expand the CC corpus and continue to search for new concepts and terms. The original corpus contains CCs from 3 southeastern teaching hospitals, and it is possible that EDs in other parts of the country or in other types of hospitals (e.g., smaller nonacademic hospitals) see different kinds of problems, or express them differently. Our intent is to identify systematic areas in which coverage is needed, rather than to attempt the impossible task of finding every last concept or term. For example, EDs in other parts of the country may see different kinds of injuries than those seen in the southeast (e.g., injuries arising from outdoor activities in cold weather, such as skiing or icefishing). We plan to partner with researchers in other parts of the country to pursue this goal. Finally, we plan to convene a symposium of experts and other stakeholders to discuss the open issues of content and policy in the design of the CC thesaurus and fields in the patient record that we have introduced in this paper. It should be noted that the development of the CC thesaurus alone is not sufficient to make CC data more readily available for use; there are additional operational issues. One concern was revealed in the ED survey (Travers et al., 2003). In North Carolina, 46% of the responding EDs reported that CC was collected on paper, rather than in electronic form. A data entry process would be required before CC data could be aggregated, and the effort and delay would make any kind of real-time surveillance infeasible. The same survey reported that all 16 EDs in Seattle collected CC electronically, but clearly one cannot assume that CCs will be immediately available from EDs in all parts of the country. A controlled vocabulary for CC is necessary to increase the utility of this data element for practice, clinical research, and health surveillance purposes. In this paper we have outlined some of the decisions that lie ahead for the thesaurus development team and the ED clinical community. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS National Library of Medicine training grant number LM07071 supported Travers’ work on this project. Funding was also provided by the North Carolina Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response in the Bioterrorism Branch of the Epidemiology Section of the Division of Public Health. The authors wish to thank members of NCEDD (http://www.ncedd.org) for technical support and helpful discussions. REFERENCES Bradley, V. (1995). Toward a common language: emergency nursing uniform data set (ENUDS). Journal of Emergency Nursing, 21(3), 248-250. Bradley, V. (1996). Innovative informatics: development of an emergency data set: a worthwhile challenge. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 22(3), 238-240. Chute, C. G. & Elkin, P. L. (1997). A clinically derived terminology: Qualification to reduction. Proceedings of the AMIA Symposium 1997, 570-574. Cimino, J. J. (1998). Desiderata for controlled medical vocabularies in the twenty-first century. Methods of Information in Medicine, 37, 394-403. Cline, S. (2000. Morbidity and mortality associated with Hurricane Floyd – North Carolina, September-October 1999. Morbidity and Mortality World Report, 49(17), 369-372. Coben, J.H., Dearwater, S.R., Garrison, H.G. & Dixon, B. W. (1996). Evaluation of the emergency department logbook for population-based surveillance of firearm-related injury. Injury Prevention, 28(1), 188-193. Greenko, J., Mostashari, F., Fine, A., & Layton, M. (2003). Clinical evaluation of the emergency medical services (EMS) ambulance dispatch-based syndromic surveillance system, New York City. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 80(2, suppl. 1). Hole, W. T. & Srinivasan, S. (2000). Discovering missed synonymy in a large concept-oriented Metathesaurus. Proceedings of the AMIA Symposium 2000, 354-358. Ivanov, O., Wagner, M. M., Chapman W. W. & Olszewski, R. T. (2002). Accuracy of three classifiers of acute gastrointestinal syndrome for syndromic surveillance. Proceedings of the AMIA Symposium 2002, 345-349. McCaig, L. F. & Burt, C. S. (2001). National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 1999 emergency department summary. Advance data from vital and health statistics; no. 320. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. release 1.0. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pollock, D.A., Adams, D. L., Bernardo, L. M., Bradley, V. Brandt, M. D. & Davis, T. E. (1998). Data elements for emergency department systems (DEEDS), release 1.0: a summary report. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 24, 35-44. Stetson, P. D., Johnson, S. B., Scotch, M. & Hripcsak, G. (2002). The sublanguage of cross-coverage. Proceedings of the AMIA Symposium 2002, 742-746. Teich. J.M., Wagner, M.M., Mackenzie, C.F. & Schafer, K.O. (2002). The informatics response in disaster, terrorism, and war. Journal of the American Medical informatics Association, 9, 97-104. Travers, D. A. (2003). Identification of Concepts from Emergency Department Text Using Natural Language Processing Techniques and The Unified Medical Language System®. Doctoral Dissertation, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Travers, D. A. & Bodenreider, O. (2002.) Identifying medical concepts in free text chief complaint data. Academic Emergency Medicine, 9, 511 (abstract). Travers, D. A. & Haas, S. W. (2003). Using nurses’ natural language entries to build a concept-oriented terminology for patients: Chief complaints in the emergency department. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 36(4-5), 260-270. McCaig, L. F. & Burt, C. S. (2003). National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2001 emergency department summary. Advance data from vital and health statistics; no. 335. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. Travers, D. A., Waller, A., Haas, S. W., Lober, W. B. & Beard, C. (2003). Emergency department data for bioterrorism surveillance: Electronic data availability, timeliness, sources and standards. Proceedings of the AMIA Symposium 2003, 664-668. McCaig, L. F. & Ly, N. (2002). National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2000 emergency department summary. Advance data from vital and health statistics; no. 326. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. Tsui, F. C., Wagner, M.M., Datao, V. & Chang, C.C. (2001). Value of ICD-9-coded chief complaints for detection of epidemics. Proceedings of the AMIA Symposium 2001, 711715. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (NCIPC). (1997). Data elements for emergency department systems,