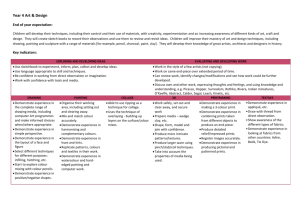

Should colours be protected by trade mark law

advertisement

SAMUEL LONDESBOROUGH LW556 – INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LAW SUPERVISOR – ALAN STORY RESEARCH DISSERTATION Should Colours be protected by trade mark law? What problems may arise in protecting them? 4,565 Words 1 ABSTRACT There has been much debate over whether or not colours should be registered as trade marks, and thus protected by law. It is true that colours do share characteristics inherent with other ‘signs’ that can be registered, and it is also true that as signs, they are able to distinguish between products. As a result, the UK, US and other countries have begun to enforce colours as trademarks. This research will examine, from a structuralist perspective, the qualities of ‘signs’, and how they are capable of distinguishing between products, whilst considering the problems associated with, and potentially arising from, registration. 2 Introduction Trade marks may represent the first contact consumers have with brands. They provide consumers with the opportunity to recognise the origin of a product, or rather, the origin of a brand, whether on product labelling, or in magazine or television advertisements. A trade mark’s ability to symbolise brands is arguably their most important function, as it is the distinction between objects, and the signification of a particular brand that provide trade marks with their economic value. Moreover, the economic function of trade marks is dependant on the identity of a brand, and viceversa. It is estimated that in 1986, Coca-Cola was worth $14billion, of which half of that figure represented the worth of the brand identity, embodied in the brand’s trade mark1. Everything embodied by the trade mark is intangible, surely highlighting their huge economic worth. Thus, the protection of trade marks becomes necessary, to protect both the sanctity of the idea of a brand, and its associated economic interest. This economic interest may also represent the driving force behind the decisions of many trade mark infringement cases – with the result perhaps being determined to provide the best economic result. Trade marks are often taken, in their everyday meaning, to represent text and logos, or basic signs, which, through special use, become associated with a particular brand. Trade marks can, however, also include colours, sounds and even scents. This dissertation will focus on the use of colours as trade marks. Drescher “The Trasnformation and Evolution of Trademarks – From Signals to Symbols to Myth” 82 TMR 301, at p301 1 3 Whilst there is nothing within the language of either the Trade Marks Act 1994, or in America, the Lanham Act, to prevent the registration of colours as trade marks, until relatively recently, the courts did prohibit this. However, in Smith, Kline and French Laboratories Ltd v Sterling-Winthrop Group Ltd2, the House of Lords held that marks can subsist as “the scheme of colouration from the coloured pattern presented to the eye”3, and that colours can constitute marks even where they cover the entire surface area of a product . By implication, this would seem to include individual colours. In order to determine if colours are able to be registered by trade mark law, this dissertation will closely examine the nature of colours as signs, and how they may be used to distinguish between products. Through this examination, the main arguments against the protection of colour trade marks will also be analysed. American cases will be referred to throughout, as they are useful in highlighting the qualities of any trade mark, although the basic definition of trade marks, as contained in the Trade Marks Act 1994, will be also be referred to. Colours as “signs” The Trade Marks Act 1994 defines a trade mark as “any sign capable of being represented graphically which is capable of distinguishing goods or services of one undertaking from those of other undertakings”4. Therefore, in order to determine if colours should be protected by trade mark law, it is necessary to establish if they are capable of being protected. Whilst it is self evident that colours, by very definition, 2 Smith, Kline and French Laboratories Ltd v Sterling-Winthrop Group Ltd [1976] RPC 511 Stated in Horton, A. A. “Designs, Shapes and Colours: A Comparison of Trademark Law in the United Kingdom and the United States” (1989) European Intellectual Property Review 11(9), 311 4 Trade Marks Act 1994 s. 1(1) 3 4 may be represented graphically, a further examination of both their nature as signs, and their consequent ability to distinguish goods, is required. A trade mark is essentially a ‘sign’, and through focusing on the nature of ‘signs’, a structuralist approach may be taken. Signs, through an ability to convey meaning, can be used to identify, narrate and even legitimise our perception of reality. When signs become attached to specific objects or ideas, both are provided with meaning. Saussure argued that within this system exists, a ‘structural relationship’, and the sign itself may be separated into both the signifier and the signified5. The former may be defined as the words, colours, shapes and sounds that infer an object or idea, and the latter, as the object itself. Barthes commented that the “associative total of signifier and signified constitutes simply the sign”6. Essentially, in the absence of either the signifier or the signified, both become devoid of meaning. A ‘table’ cannot exist without the notion of table and the notion cannot exist without the table itself. Whilst the above is especially true of spoken language, it may also be applied to nonverbal forms of communication, including image representations7. Images, working as signs, may be classified as either icons, indexes, or symbols8. The Icon functions as a sign through a resemblance with an actual object, the index, through a factual or causal connection with an object, and the symbol, through a rule associating itself with an object9. Colours may operate as signs in all three categories. For example, as 5 Saussure, in his Course in General Linguistics, pioneered the scientific study of language as a series of signs. 6 Roland Barthes’ Mythologies, discussed in Structuralism and Semiotics, Hawkes, 1977, p130-134 7 “It is…clear that human beings communicate by non-verbal means and in ways which must consequently be said to be either non-linguistic or which must have the effect of ‘stretching’ our concept of language until it includes non-verbal areas” (Hawkes, Structuralism and Semiotics, 1977, p125). 8 Argued by Pierce, in his Collected Papers (1931-58), and discussed in Hawkes, 1977, p127 9 Ibid 5 demonstrated by Re Owens-Corning10, the colour pink may symbolise roof insulation, by virtue of both its physical resemblance to, and factual connection with pink roof insulation. Also, through the creation of a myth, examined below, the sign, “pink” may associate itself with roof insulation. It is arguable that most trade marks are composed of a number of signs, including text, shapes and colours, which, when used in conjunction, work to communicate specific ideas. In this context, the signs are interdependent, and are unable to operate individually. A series of words forming a single, unique sign can be registered as a trade mark. However, single generic words cannot. For example, the word ‘cup’, a generic term, could not be registered as a trade mark for a cup because doing so would prevent all other cups from being labelled as such. Colours are generic and are widely used, so should the same not be applied? Moreover, it may be argued that colours do not possess the arbitrary qualities of other visual signs11. However, are individual colours still capable of possessing the same distinctive qualities as those marks containing a series of signs? It was argued by the defence in the US case of Qualitex v Jacobson12, that there is no need for the protection of colours because they may be contained within other trade marks13. Whilst this notion was rejected by the court, such an argument obviously offers no protection to stand alone colours. 10 Re Owens-Corning Fiberglass Corp. 774 F.2d 1116 (1985) “[In Re Owens-Corning Fiberglass Corp.] A dissenting judge argued that to function as a trade mark colour must be confined to "some definite arbitrary symbol of design'.” Horton, “Designs, Shapes and Colours: A Comparison of Trademark Law in the United Kingdom and the United States” (1989) EIPR 11(9), 311 at p314 12 Qualitex Co. v Jacobson Products Co. 514 U.S. 1300 159 (1994) 13 Discussed in Schwarz, “The Registration of Colours as Trade Marks” (1995) EIPR 17(8) 393, at p395 11 6 Colours, even in isolation can become attached to a particular object or idea, and indeed do. Red has come to signify passion and green, envy, and therefore, when we see, or think of these colours we may therefore be reminded of all their associated denotations and connotations. Colours are, however, non-arbitrary, and thus, in order to work as viable symbols, require the creation of new connotations. The process of attachment, through which signifiers become anchored to particular objects, is essentially cultural, and is therefore determined by the particular shared ideologies of a society at any given time. As such, society may agree that the word ‘table’ should refer to an actual table, or the colour red to passion, and so on. Consequently, the ‘sign’ may, over time become synonymous with the thing itself, and be codified. It is obvious that the more a sign is used in a particular context, and the more it is recognised by sectors of society, it will be more readily anchored to an object or idea. With regard to trade marks, this may be achieved through intensive advertising aimed at target consumers, eventually leading to a strong associative relationship between the mark, and a particular product. It may be argued that this is indeed a necessary process in establishing individual colours as viable signs. Whilst other trade marks, including brand names, may be instantly recognisable owing to unique characteristics, the generic nature of individual colours may make it necessary to establish a new meaning that can be uniquely identified with a specific product, and this must be achieved through advertising. In other words, it is the connotation of the colour sign that is important in establishing uniqueness, not the sign itself. 7 ‘Myths’ It appears that once a sign is anchored, it is set in stone. On the contrary, the process of attachment and codification is fluid, and signs may repeatedly adopt new meaning. This is important if colours are to align themselves with certain products and brands. Where there is a well established sign, it may attract secondary meaning through either extended use, or the creation of ‘myths’. Barthes defines a myth as “the complex system of images and beliefs which a society constructs in order to sustain and authenticate its own sense of being”14. Myths are carved out of signs, although will provide the symbol with new meaning beyond that of the original sign. As Barthes argues, the associative total of the pre-existing sign equals the signifier, or ‘form’ of the myth. This, in conjunction with its signified, or ‘concept’ forms the signification. Myths may be created through either a products continued association with a specific colour, whereby the products own myth is transferred to the colour, or where brand owners actively formulate a myth through advertising campaigns. In any case, advertising will certainly help to speed up the process though which society attaches particular meaning to a colour symbol. To use ‘Nike’ as an example, the Nike symbol will, on a basic level, signify Nike products. However, attached to these products is a ‘myth’ of quality, sportsmanship and youth culture. This is because Nike trainers are used by professional sportspeople, and, through both the passage of time, and a series of rigorous advertising campaigns, have attached themselves to youth culture. The Nike symbol, used in all advertising, represents the brand, and its connotations must therefore typify everything the myth 14 Cited in Hawkes, Structuralism and Semiotics, 1977, p131 8 purports. Drescher argues that “the myth which obsesses the mark on a symbolic level insinuates itself into the product denoted by the mark at the material level”15. Therefore, the brand, the sign, and the myth become inextricably linked. Barthes argues that in some situations, the myth may nullify the meaning of the pre-existing sign, “in other words, myth operates by taking a previously established sign (which is ‘full’ of signification) and ‘draining’ it until it becomes an ‘empty’ signifier”16, and it is this that allows myths to attach new meanings to colours. For example, the colour red, which is normally taken to signify passion, could be used as a mark for branded construction tools. Through extensive use, this colour will become the signifier for that particular brand. That product’s own mythical system may then be eventually transferred to the colour itself, so that the colour effectively becomes a representation of the myth. Additionally, the brand-owners may, through advertising, choose to construct a myth that, within the context of power tools, will eventually separate the colour red from its original meaning, giving it new identity. The myth, as previously explained, creates a new hierarchy of meaning, or ‘secondary meaning’. In Qualitex v Jacobson Products Co17, it was held that by virtue of a particular myth, a product is taken to have acquired this new secondary meaning “when in the minds of the public, the primary significance of a product feature…is to identify the source of the product rather than the product itself”18. Therefore, the importance of a myth in its capacity to denote origin, and therefore a whole set of other assumptions such as product quality, must not be underestimated. Drescher, “The Transformation and Evolution of Trademarks – From Signals to Symbols to Myth”, 82 TMR 301, p310 16 Ibid 17 Qualitex Co. v Jacobson Products Co. 514 U.S. 1300 159 (1994) 18 Ibid, at p163 15 9 The quality associated with particular brands and their trade marks may therefore be primarily attributed to the communication of myths. In the consumer consciousness, a product with a certain sign may appear ‘better’ than generic products. A pair of Nike trainers, for example, may be viewed as better than a pair of unbranded trainers, simply because they carry the famous ‘Nike swoosh’. If associated with a particular brand, the same can certainly be applied to colours. The colour of a leading brand’s products and their packaging may sometimes become synonymous with the type of product itself “as a form of generic code or visual cue”19, and so it may be argued that its use by others is justifiable. In the UK, the supermarket chain Sainsbury’s used a gold lid for their premium coffee20, although the brand leaders of coffee, Nescafé, had also produced packaging with a gold coloured lid21. The quality associated with Nescafé had become attached to its gold coloured lid, and, it may be argued, therefore became synonymous with the quality of certain types of coffee. In other words, a consumer would perhaps only recognise a jar of coffee as being of good quality if it had gold coloured packaging. In the US case of Inwood Laboratories Inc. v Ives Laboratories Inc22, the same colouring was used for both a generic and branded drug. It was held that because consumers associated the colouring of the drugs with their ability to heal, the colouration served a functional purpose. A sign is functional “if it is essential to the use or purpose of the article or it affects the cost and quality of the article”23. Despite 19 Mills, cited in Trade Marks in Theory and Practice, p149 Ibid 21 Ibid 22 Inwood Laboratories Inc v Ives Laboratories Inc. 456 US 844 (1983) 23 Ibid, at p850 20 10 this, it may be argued that colour itself, as an aesthetic medium, is rarely integral to a product’s utility24, except perhaps where it exists as a stand-alone sign. If a colour does form an integral part of a product, and must be imitated to ensure the commercial success of the competition, it may be argued that its use should not be restricted.. This approach, taken by the District Court in the aforementioned case and upheld by the Supreme Court, seems rather cynical, as rather than promoting the free use of generic signs, it seems more focused on ensuring the continuation of a healthy economy. However, with this is mind, it must be reconsidered that the main reason behind the protection of intellectual property, and particularly trade marks, is to ensure their economic exploitation. In addition to communicating rudimentary ideas that already circulate within a society, colours can also communicate specific ideas from one individual or group, to another, indicating origin. This is clear in the case of the artist, who communicates their ideas to the viewer through their painting. Moreover, the viewer is aware of the origin of those ideas – it is clear that the painting was created by that artist. This may also be applied to colour marks. As previously explained, forms of advertising communicate specific ideas about a product or brand from the brand-owner to the consumer, and may be used to perpetuate a myth and establish new colour signification. When viewed, a sign may then both denote the origin of a product, and relay the ideas communicated by the myth. When considering all of the above, it becomes apparent that colours can operate as viable signs, however, do they truly have an ability to distinguish between brands? 24 Schwarz, “The Registration of Colours as Trade Marks” (1995) EIPR 17(8) 393, at p394 11 An ability to distinguish? The very nature of signs dictates that they must be capable of distinguishing between other signs, and thus distinguish between objects and ideas. For example, within our linguistic system, we are able to distinguish between individual words. As such, there will often be little confusion over the ideas communicated. Although individual colours can be distinguished between, there are only a finite number of colours available for use, and this may cause problems if individual colours are to be registered as trade marks. Moreover, where the same colour is used more than once, the signified may become confused. Whilst it may be argued that the finite number of existing colours would render it impossible to distinguish between goods, it may be counter-argued that because colours are by nature polysemic, that is, capable of conveying many different ideas, they can, if used in a particular context, distinguish between products. The language in s.1(1) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 only requires that signs are able to distinguish between products of different undertakings, and so if this is satisfied, the colour in question will be capable of being registered as a trade mark. Where a single colour is used by more than one company for similar products, or visaversa, it follows that the sign will fail to be unique. Under s.3(1)(b) of the Trade Marks Act 1994, registration of a mark will be refused if it devoid of any distinctive character, that is to say where it is identical with an earlier mark and used for identical goods. Registration may also be refused under s.5(2) of the 1994 Act, where a sign is identical with an earlier mark and is to be registered for similar goods, or where a similar mark is to be registered for identical goods. This would implicate that similar 12 colours, as non-arbitrary signs, should not be used for like goods. When assessing the distinctiveness of a colour, the possibility of confusion between signs must be addressed. In infringement proceedings, the court will assess at what point a colour becomes too similar with a pre-existing trade mark, quantifying the “likelihood of confusion”25. If a consumer cannot distinguish between products by virtue of their mark, there is shade confusion. Therefore, the sign may not be distinct enough and under s. 5(2) of the Trade Marks Act 1994, may not be registered as a trade mark. However, it must be recognised that the theory of shade confusion in itself is not a viable argument against the general protection of colours as trade marks, as the courts must always assess the likelihood of confusion as a necessary portion of any trade mark infringement action26. Within the UK, there has been contention between EasyGroup, and Orange Telecommunications27, whose coloured symbols, each a bright orange, are virtually identical. EasyGroup proposes use of their colour sign within the telecommunications industry. Their (unregistered) sign has gained a degree of secondary meaning in its ability to identify the origin of their products, including budget airline services and banking. However, Orange holds a trade mark for its shade of orange ‘pantone 151’, and whilst the shades are subtly different, with each communicating different ideas to the user, it may be argued that their concurrent use within the telecommunications industry would cause shade-confusion amongst consumers, and thus render EasyGroup’s sign indistinctive. Within the 1994 Act, it is therefore seems unlikely Schmidt, “Creating Protectible Color Trademarks” (1991) 81 TMR 285, at p289 The colour confusion theory was rejected by Qualitex for this reason. Schwarz, “The Registration of Colours as Trade Marks” (1995) EIPR 17(8) 393, at p394/5 27 Reported in “Easy brand’s future may not be orange”, Day, J, The Guardian Newspaper, 16th August 2004 25 26 13 that EasyGroup’s symbol will be registered as a trade mark for telecommunications, or will succeed in an action against Orange. Whilst marks subsisting as a series of signs are usually able to distinguish between similar products, for example, Vodafone’s sign is distinguishable from Orange’s, with individual signs such as colours, this can become difficult. Therefore, the context in which colours are used, and myths used to create secondary meanings, become important in establishing and maintaining distinctiveness. If, through the process of attachment outlined above, a colour becomes synonymous with a product, then it may be argued that it has gained ‘secondary meaning’ and is thus distinctive. In the case of Re Owens-Corning Fiberglass Corp28, it was held that the colour pink, through being used by the applicant to colour their fibreglass for a number of years, had acquired a ‘secondary meaning’. Through this, consumers associated the colour pink solely with their fibreglass. The same was essentially held in Qualitex29. In this case, the petitioners had used a green-gold colour for the press pads they had manufactured since 1957, although in 1991, the respondent company began using a similar colour on their own press pads. In determining whether or the green gold of Qualitex’s press pads had gained distinctiveness, the court looked to whether or not, through being associated with the manufacturer, the colour had gained a new secondary meaning. As explained above, through the process of attachment, this secondary meaning may essentially be achieved through continued use of a particular colour as a symbol, 28 29 Re Owens-Corning Fiberglass Corp. 774 F.2d 1116 (1985) Qualitex Co. v Jacobson Products Co. 514 U.S. 1300 159 (1994) 14 which will in time incorporate certain ‘myths’. However, as the court argued in Qualitex, this is dependant on the exclusivity of colour use with regard to a specific product. It may be argued that where several products concurrently use similar colours, the colour cannot attach more meaning to one product than the other and vice-versa, and thus, no one product is more worthy of gaining trade mark protection than the other. Moreover, the co-existence of two non-arbitrary symbols may lead to confusion amongst consumers, surely defeating the rationale behind the existence of the trade mark, the primary function of which is to allow consumes to distinguish between products30. In addition to assessing the exclusivity of the colour, the court also assessed how the product was advertised. The court may additionally consider consumer surveys to determine if the colour has acquired a secondary meaning. After distinctiveness is established, the court must then determine the functionality of the symbol. This effectively means that where a sign is fundamental to the social utility of a product, or constitutes its natural colour, then it is cannot distinctive, and should not be registered as a mark31. Colour Depletion As previously explained, if a colour is able to exist as a sign and distinguish between products, then it can be registered as a trade mark. Once a colour has overcome the hurdle of establishing itself as a distinctive sign, there are further practical arguments against its protection as a trade mark. These are, the theories of colour depletion and 30 See Introduction Discussed in Schmidt, “Creating Protectible Color Trademarks”, (1991) 81 TMR 285, at p288. Also see p7 of this dissertation where I discuss functionality with regard to the assimilation of generic product type and the signs of branded products. 31 15 shade confusion, and the doctrine of functionality32. The latter two have already been examined above, and remain important in considering the distinctiveness of a sign. Colour depletion purports that there are a limited number of colours, and so where colour signs are registered as trade marks, the number that remain available to other brand-owners becomes restricted. Moreover, as more colours are registered as marks, the number will continue to deplete. In Campbell Soup Co. v Armour & Co.33, the plaintiff company, who are known for the famous red and white labelling used on their food products, sought to prevent the defendant’s from using the same coloured packaging on their respective food products. Whilst it is clear today that these colours existed together as a distinctive sign, it was held that the plaintiff’s were wrong in requesting the right to have exclusive use of the coloured sign. The exclusive use of a sign leads to monopolisation, and permitting the use of the colour mark in that case would in turn allow other manufacturers to monopolise other colours, until the list of available colours becomes depleted. However, this theory was rejected by the US Supreme Court in Qualitex, which held that a limited colour supply in some industries did not justify a ‘blanket protection’, as in most cases, enough colours are available for use34. Such reasoning may be attributed to a need to ensure the continued commercial exploitation of signs as marks, particularly within the context of the fairly recent drive towards the creation and subsequent registration of colour marks35. Outlined by Schmidt in “Creating Protectible Color Trademarks” (1991) 81 TMR 285 Campbell Soup Co. v Armour & Co. 175 F2d 795 (1945) 34 Schwarz, “The Registration of Colours as Trade Marks” (1995) EIPR 17(8) 393, at p395 35 Theories such as colour depletion and shade confusion had restricted the use of colours as marks. As such, although there was no clear statutory definition of ‘trade mark’ within the US ‘Lanham Act’ which explicitly or impliedly barred the exclusive use of colour, the courts were nonetheless, by virtue of the aforementioned predominant arguments, extremely reluctant to offer colour marks any protection. Only within the past twenty years has there been a move towards the relaxation of these theories and the protection of colours as trade marks, culminating with the case of Qualitex. This case dismissed all criticisms of the protected usage of colour signs except ‘functionaility’. 32 33 16 In any case, it may still be argued that the use of individual colours as marks may lead to colour depletion. If the creation of marks is dependant on the free use of individual signs, then colour depletion will inhibit the creation of new marks, and thus a brandholders ability to communicate ideas about their products will be seriously compromised. As previously explained, signs are capable of communicating various ideas, including the origin of a product, its brand image, and even its quality. Thus, if brand-owners are unable to convey these ideas through their marks, they may be placed at a disadvantage with the consumer. As a result, their products may, through a lack of unique branding, even be perceived as generic. Producers may also lose the opportunity to charge inflated prices for their goods. The cost of a product is often determined by how it is branded, with its mythical associations often legitimising its price. As previously explained36, the value of most large brand- holding companies is calculated through the value of its real property and intellectual property. With regard to the latter, where a company is unable to establish a solid brand identity that becomes anchored to a sign, it may be argued that it will have no discourse within society. Therefore, the value of the ‘brand’ will not be quantified, and consequently, the value of the company will be negatively impacted upon. Lastly, it may be argued that the protection of a finite number of colours may lead to an increased number of infringement litigations where every other colour mark infringes each registered colour trade mark. Moreover, how could these colours be enforced in different countries, where different significations dictate their meaning? 36 See introduction 17 Conclusion In conclusion, the structuralist critique of colours as signs highlights that they can, even in isolation, operate as fully functional language systems, and as such, work to distinguish between products. This is established particularly through the perpetuation of myths, which serve to attach further secondary meaning to pre-established signs. Therefore, colours can function as trade marks, and are indeed able to satisfy the requirements of the Trade Marks Act 1994, allowing them to be registered. A structuralist examination of colours reveals that there are no real reasons why colours should not be protected by trade mark law. On the contrary, this is encouraged by their functions as signs. However, where the same colour is used to represent a product of a different undertaking than the registered mark, the structural system of the registered may begin to erode unless it is firmly rooted in the consciousness of a society. It is this consciousness that allows people to distinguish between goods. Shade confusion appears to represent a persuasive argument against the protection of colours as trade marks, although, as demonstrated, only becomes an issue when determining if there is trade mark infringement. The theory of colour depletion is persuasive, and demonstrates that unless there is stricter control with regard to the registration of colour marks, then it could become a problem. All of the possible effects of colour depletion outlined above work to defeat the very notion governing the protection of trade marks, which, as with all forms of intellectual property, is to secure commercial exploitation. Through the process of colour depletion, brands will grow unsustainable, and markets will become controlled by a select few colour trade mark holders, eliminating free competition. A balance should be struck between both the need to promote the creation of colour signs, which itself requires the freedom to 18 use colours, and the protection of those signs, which will restrict the number of colours that can be used. This could be achieved through the creation of a statutory procedure specifically governing the use of colours as trade marks, that goes beyond the ‘secondary meaning’ test of Qualitex. Despite this, individual colours are not exclusively representative of all trade marks, and most marks are made up of many signs that work together to communicate meaning. A huge reservoir of potential marks, coupled with an exact ability to distinguish between existing marks, including colours, could counter the effects of colour depletion. 19 Bibliography Books Hawkes, T. Structuralism and Semiotics, Methuen, London, 1977 Phillips, J. Trademark Law: A Practical Anatomy, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2003 Pickering, C. D. G. Trade Marks in Theory and Practice, Hart, Oxford, 1998 Articles Doll, A. “Registrability of Stand-alone Colors as Trademarks” (2001) 12 Journal of Contemporary Legal Issues 66 Drescher, T. D. “The Transformation and Evolution of Trademarks – From Signals to Symbols to Myth” 82 The Trademark Reporter 301 Horton, A. A. “Designs, Shapes and Colours: A Comparison of Trademark Law in the United Kingdom and the United States” (1989) European Intellectual Property Review 11(9), 311 Schmidt, T. S. “Creating Protectible Color Trademarks” (1991) 81 The Trademark Reporter 285 Schulze, C. “Registering Colour Trademarks in the European Union” (2003) European Intellectual Property Review 25(2), 55 Schwarz, M. ‘Registration of colours as trade marks’, (1995) European Intellectual Property Review 17(8), 393 Sim, K. R. and Tonner, H. “Protecting Colour Marks in Canada” (2004) 94 The Trademark Reporter 761 20 Stevens, T. “The Protection of Trade Dress and Color Marks in Australia” (2003) 93 The Trademark Reporter 1382 Vana, J. L. “Color Trademarks” (1999), 7 Texas Intellectual Property Law Journal 387 Vick, J. E. “The Color of Money – Trademark and Trade Dress Protection of Product Coloration” (1994) 57 Texas Bar Journal 600 Visintine, L. R. “The Registrability of Color per se as a Trademark after Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Products Co” (1995-6) 40 St. Louis Univeristy Law Journal 611 “Colours Alone Can Form Trade Mark” (2004) EU Focus 148, 17 Cases U.S. Qualitex Co. v Jacobson Products Co. 514 U.S. 1300 159 (1994) Re. Owens-Corning Fiberglas Corp. 774 F.2d 1116 (1985) Campbell Soup Co. v Armour & Co. 175 F2d 795 (1945) Inwood Laboratories Inc v Ives Laboratories Inc. 456 US 844 (1983) UK Statutes Trade Marks Act 1994 Other 21 “Easy brand's future may not be orange”, by Julia Day, The Guardian Newspaper, Monday August 16th 2004 “Trademarking Colours”, by Julia Day, The Guardian Newspaper, Monday August 16th 2004 “Executive Intellectual Property Bulletin”, Schwegman, Lundberg, Woessner, Kluth, http://www.slwk.com/CM/IPBulletins/IPBulletins30.asp “Color Matters: Who Owns Hues – Color Trademark Disputes”, by Jill Morton, www.colormatters.com/color_trademark.html “Supreme Court Allows Color to be Registered as a Trademark”, April 6th 1995, Gibney, Anthony and Flaherty LLP, http://www.gibney.com/LegalNews/Record/colortrademark.cfm 22