Directing and Managing Conflicts of Interest in Sponsored Research

advertisement

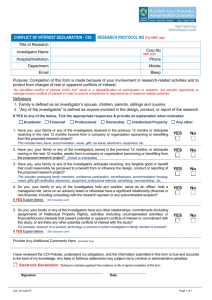

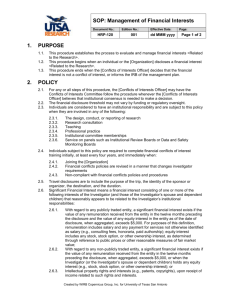

DIRECTING AND MANAGING CONFLICTS OF INTEREST IN SPONSORED RESEARCH October 30-November 1, 2002 Jeanine Arden Ornt, Esq. General Counsel to the University of Rochester University of Rochester Rochester, New York PART TWO: APPLICABLE LAW AND GOVERNMENTAL REGULATIONS I) BACKGROUND A) The federal governmental funding agencies (HHS (PHS, NIH); NSF) have imposed upon applicants/grantees the responsibility to promote objectivity in research for which funding is sought. B) Following a Congressional Inquiry in the 1980’s, Congress mandated the National Institutes of Health (“NIH”) to regulate financial conflicts of interests. The initial focus was on the researchers’ conflicts, but as we will see, the concept has recently evolved to include both the university and the researchers’ potential conflicts. C) The NIH responded through its NIH Guide (January 1989): 1) Solicitation for Comments regarding Extramural Researchers’ Financial Conflicts of Interest. This solicitation focused on circumstances that might affect objectivity or appear to affect objectivity including circumstances where the research could either benefit, or be perceived to benefit, the financial interests of the researcher or his/her immediate family. 2) There was general agreement that institutions receiving NIH funds needed to adopt conflicts of interest policies to identify and manage conflicts of interest. Again, the initial focus was on the investigators’, rather than the institutions’, conflicts. 3) Regulations a. In September 1989, the NIH issued the first draft of regulations. The underlying rationale of the first regulations, finally published in 1995, was to establish standards and procedures to be followed by PHS-funded institutions to ensure that the design, conduct or reporting of such research would not be biased by any conflicting financial interest of those investigators responsible for the research. b. In July 1995, National Science Foundation (“NSF”) “Investigator Financial Disclosure Policy” (now changed to “Conflicts of Interest Policies”) & Public Health Service (“PHS”) published final rules (PHS: http://grants2.nih.gov/grants/guide/noticefiles/not95-179.html and NSF: http://www.nsf.gov/bfa/cpo/gpm95/ch5.htm#ch5-6) which in large part, parallel the NIH regulations. c. The regulations impact all extramural research and development funded by the PHS or NSF respectively. These regulations establish standards and procedures to be followed by institutions that apply for research funding from the PHS (or NSF) to ensure that the design, conduct, or reporting of research funded under grants, cooperative agreements or contracts will not be biased by any conflicting financial interest of those investigators responsible in any way for the research. d. The FDA has had regulations requiring financial disclosure for clinical investigators since 1998. D) Scope: All Research, Not Limited to Clinical Research National Association of College and University Attorneys 1 1) As explained in the preamble to the Notice to Proposed Rule Making (“NPRM”) for the PHS regulations, the government concluded that experience has shown that financial conflicts of interest can arise in all types of research. While the government recognized that the risk of conflicts of interest will be higher in clinical research than in other types of research, the government concluded that the risk in all types of research was sufficiently likely and, therefore, that financial interests should be disclosed and reviewed for all research. 2) However, it is worth noting that the NIH regulations do not apply to SBIR and STTR Phase I applications. II) NIH REGULATIONS A) Purpose: Protect Objectivity in Research 1) Many states also regulate conflicts of interest but for purposes of today’s discussion, I am focusing exclusively on the federal regulations. 2) The NIH regulations require that “[e]ach Institution must: [m]aintain an appropriate written, enforced policy on Conflicts of Interest…and inform each Investigator of that policy, the Investigator’s reporting responsibilities and of these regulations” (42 CFR 50.604(a)). In summary, the regulations require that each Investigator disclose all “significant financial interests”: a. that would reasonably appear to be affected by the PHS-funded research; or b. in entities whose financial interest would reasonably appear to be affected by the research. (Worm: Disclosure Cartoon) B) Key Terms for Purposes of Understanding NIH Regulations: Note: Institutions may adopt more rigorous standards than the federal definition, but not less vigorous. (Devil: Conscience Cartoon) 1) Significant Financial Interest anything of monetary value, including but not limited to, salary or other payments for services (consulting fees or honoraria); equity interests (stocks, stock options or other ownership interests); and intellectual property rights (patents, copyrights and royalties from such rights). The term does not include: salary, royalties, or other remuneration from the applicant institution; any ownership interests in the institution, if the institution is an applicant under the SBIR or STTR Programs, Phase I; income from seminars, lectures, or teaching engagements sponsored by public or nonprofit entities; income from service on advisory committees or review panels for public or nonprofit entities; an equity interest that when aggregated for the Investigator and the Investigator's spouse and dependent children, meets both of the following tests: does not exceed $10,000 in value as determined through reference to public prices or other reasonable measures of fair market value, and does not represent more than a five percent ownership interest in any single entity; or salary, royalties or other payments that when aggregated for the Investigator and the Investigator's spouse and dependent children over the next twelve months, are not expected to exceed $10,000. 2) Investigator Principal investigator and any other person who is responsible for the design, conduct, or reporting of research funded or proposed for funding by PHS. National Association of College and University Attorneys 2 3) Research Systematic investigation designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge relating broadly to public health, including behavioral and social-sciences research. The terms encompass basic and applied research and product development. The term includes any activity for which research funding is available from a PHS Awarding Component through a grant or cooperative agreement, whether authorized under the PHS Act or other statutory authority. C) Institutional Conflicts of Interest are not addressed in the current regulations. The government has recognized the need to carefully consider that issue through a separate process and through a separate rule (which is anticipated within the next 1-2 years). D) Fundamental Elements: Disclosure, Management, Reporting, Sanctions 1) Disclosure Under the NIH regulations, an institution’s policy must require all investigators with a substantial research responsibility to file a financial disclosure form with the institution; this disclosure form identifies any significant financial interests of the investigator, his/her spouse and dependent children, that would reasonably appear to be affected by the proposed research or in any entities that would reasonably appear to be affected by the research. It is the investigator’s responsibility to consider ALL significant financial interests. However, the federal regulations require the investigator to actually disclose only those which would reasonably appear to be affected by the specific research proposal. a. Again, an institution may require greater, but not lesser, disclosure than that required by the federal regulations. b. Financial Disclosure Form: the Investigators must file either annually or as new reportable significant financial interests are obtained. c. While Institutions may choose either of these disclosure update periods, many institutions opt for the annual reporting because it serves as a reminder to the investigators to assess prior disclosures, as well as an opportunity for the institutions to review all forms. Therefore, those institution’s policies require an annual disclosure plus more frequent than annual disclosures of new significant financial interest determined to exist. d. The existence of a significant financial interest does not, alone, create a conflict of interest. Rather, there must be a nexus between the significant financial interest and the scope of the research to be performed by the investigator(s). e. Note that institutions are not required to “ensure” that Investigators have disclosed all significant financial interests, but must “require” all investigators to disclose. 2) Management In contrast to the first element – disclosure -- which is the responsibility of the individual investigator, the second element – management -- is the responsibility of the institution. a. Note: At this time, the management responsibility relates solely to the investigators’ conflicts; the NIH is currently considering how to address the management of institutional conflicts of interest. b. The purpose of the institutions’ management responsibilities is to reduce, manage or eliminate the risk that the conflict of interest poses to the credibility of the research. These responsibilities may be divided into two main categories: Procedural Management Responsibilities and Substantive Management Responsibilities. c. Procedural Management Responsibilities (i) Acquire and Maintain Data. The sponsoring institution’s management responsibilities include the following: (1) Maintaining a written policy on Conflicts of Interest, consistent with the NIH regulations; National Association of College and University Attorneys 3 Informing each investigator of the policy, the investigator’s reporting responsibilities, and the NIH regulations; (3) Obtaining assurances from – or otherwise assuring compliance by – all subgrantees, contractor or collaborators through which the institution carries out PHS-funded research; (4) Designating institutional officials to obtain and review all financial disclosure statements from all PHS-funded Investigators; in order to do so, the institution must require, by the time an application is submitted to PHS, each Investigator to have submitted a listing of all Significant Financial Interests (with the “nexus” described above); (5) Providing guidelines for the designated institutional officials to identify conflicts of interest; (6) Maintaining records, of all financial disclosures and all actions taken by the institution regarding each conflict of interest, for at least three years from the date of submission of the final expenditure report (or other dates specified in 45 CFR 74.53(b)); (7) Establishing adequate enforcement mechanisms and providing for sanctions; (8) Certifying in each application for PHS funding that the institution has a written and enforced administrative process to identify and manage conflicts of interest; (9) Reporting, to the PHS “Awarding Component” (prior to the institution’s expenditure of any fund under the award); any conflicting interest identified by the institution and assuring that the interest has been managed, reduced or eliminated; a. this report need NOT describe the nature of the conflict of interest or any other details b. if the institution identifies any conflict of interest after the initial report, a subsequent report must be made within sixty (60) days of identification; (10) Making available to HHS, upon request, all information relating to conflicts of interest. d. Substantive Management Responsibilities: (i) Assess and Manage. In addition to complying with the above “Processes,” the institutions are required to do the following in order to manage, reduce or eliminate conflicts of interest: (1) Review all financial disclosure forms and make a determination whether a conflict of interest exists. (Collecting the forms is challenging enough; finding the time and expertise needed to actually review and make determinations from the forms is very difficult.) (a) Recall the NIH definition of conflict of interest: a conflict of interest exists when the designated official(s) reasonably determines that a significant financial interest could directly and significantly affect the design, conduct or reporting of the PHS-funded research. (42 CFR Part 50.605(2)). (2) Determine who is an “Investigator.” The NIH determined that “based on their knowledge of the specific institutions, the institutions are in the best position to determine who is responsible for the design, conduct or reporting of the research to such a degree that his/her financial interest should be reviewed.” NIH Guide, Vol. 24, No. 25, July 14, 1995 (¶ 3 regarding 50.603 Definitions). (3) Determine what actions should be taken by the institution in order to achieve the desired purpose: reduction, management, or elimination of the conflict of interest. (2) National Association of College and University Attorneys 4 The regulations cite the following examples of actions an institution may take, recognizing that these are not all-inclusive: Public disclosure of significant financial interests (in publications, presentations, to students and other research staff); Monitoring of research by independent reviewers; Modification of the research plan; Disqualification from participation in all or a portion of the research funded by the PHS; Divestiture of significant financial interests; or Severance of relationships that create actual or potential conflicts. The NSF regulations cite other management examples including: Segregation of graduate students from any conflict of interest situation of the student’s mentor, Requiring regular reporting (more often than annually) to the Dean, Conflict of Interest Committee or other institutional authority, Identification of “Overseer” or Oversight Committee who/which has the responsibility to oversee the research and investigator on a regular basis and to report any issues or concerns to institutional authority, Modification of research plan, Divestiture (temporarily through a trust or permanent) of the investigator’s equity interest, Appointment of an alternative investigator (with sponsoring entity’s approval) who may act independently of the conflicted investigator, Disqualification from participation in all or part of the federally-funded research, Severance of the relationship that creates the conflict of interest situation, Elimination of the conflict of interest: this is an extreme measure and generally considered only when other management options are deemed ineffective. This issue arises most frequently in the context of clinical and other human subject research. If faced with prohibition, the investigator/faculty member then has the difficult decision of foregoing a business opportunity or leaving his position at the institution. (4) Promptly notify the PHS Awarding Component of any corrective action the institution is considering for an investigator who failed to comply with the conflict of interest policy, or who has biased the design, conduct or reporting of the research. The PHS will consider the institution’s corrective action, take appropriate action or refer the matter to the Institution for further action. (5) Submit for review by HHS, upon request, the institutional procedures and actions regarding conflicts of interest, including all pertinent records: (a) HHS “to extent permitted by law” will maintain confidentiality of all records of financial interest. (b) On basis of this review, HHS may decide that a particular conflict of interest will so bias the research that either further action is needed or funding must be suspended. (6) Require the Investigator to disclose the conflict of interest in each public presentation of the research results, in all cases wherein the HHS determines that National Association of College and University Attorneys 5 clinical research has been designed, conducted, or reported by an Investigator with a conflict of interest that was not disclosed or managed appropriately. (7) Exceptions: If management restrictions would be ineffective or inequitable, and the potential negative impact of prohibiting the research due to a significant financial interest is outweighed by interests of scientific progress, technology transfer, or public health and welfare, then the research may be allowed to go forward without imposing such conditions or restrictions. 3) Reporting If a Conflict of Interest is determined to exist after the submission of the application, the institution must (prior to any expenditure of awarded funds): a. Report the existence of such conflicting interests to the Public Health Service Awarding Component (but not the nature of the interest or other details); b. Assure that the interest has been managed, reduced or eliminated in accordance with the regulations (to the extent verifiable); c. Act to protect PHS-funded research from bias due to the conflict of interest; d. For any interest that the Institution identifies as conflicting subsequent to the Institution’s initial report under the award, make the report and describe how the conflicting interest is being managed, reduced, or eliminated, at least on an interim basis, within sixty days of that identification. e. If the conflict of interest has biased the design, conduct, or reporting of the PHS-funded research, the Institution must promptly notify the PHS Awarding Component of the corrective action taken or to be taken. The PHS Awarding Component will consider the situation and, as necessary, take appropriate action, or refer the matter to the Institution for further action, which may include directions to the Institution on how to maintain appropriate objectivity in the funded project. f. Note: The requirement to report to PHS is not consistent with the NSF, which requires reporting only if the institution is unable to satisfactorily manage a Conflict of Interest. The institution must keep the NSF Office of the General Counsel informed if the institution is unable to satisfactorily manage a Conflict of Interest. g. Maintain records of all financial disclosures and of all actions taken to resolve conflicts of interest for at least three years beyond the termination or completion of the grant to which they relate, or until the resolution of any governmental action involving those records, whichever is longer. 4) Sanctions a. Access to records: The federal regulations (45 CFR 74.53) provide the government with the authority to have access to all records pertaining to grants, which would include the records relating to financial conflicts of interest of investigators carrying out the funded research. The exception is that the funding agencies will require the submission of records or retain copies from audits at the institution rarely, but when that occurs the records will be maintained confidentially “to the extent possible.” b. Suspension: such suspension action would be necessary to protect Federal funds only in unusual situations. The PHS Awarding Component may determine that suspension of funding under 45 CFR 74.62 is necessary until the matter is resolved. 5) Final Note On December 1, 2000, the Public Health Service announced a new "PHS Policy on Instruction in the Responsible Conduct of Research (RCR)" which requires institutions to establish an education program on certain core areas of instruction for responsible research (including conflict of interest and commitment) for research staff at the institution who have direct and substantive involvement in proposing, performing, reviewing, or reporting National Association of College and University Attorneys 6 research, or who receive research training, supported by PHS funds or who otherwise work on the PHS-supported research project even if the individual does not receive PHS support. The research institution may make reasonable determinations regarding which research staff fall within this definition. For more information on the RCR policy, including the full text and commonly asked questions and answers, see the ORI website http://ori.hhs.gov under "news." III) RECENT FOCUS ON HUMAN SUBJECT RESEARCH AND THE RISKS THAT CONFLICTS OF INTEREST MAY POSE 1) University of Pennsylvania gene therapy death of 18 year-old boy, Jesse Gelsinger a. The principal investigator for this study reportedly had a financial interest in the company sponsoring the study. “The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has asserted that Gelsinger, who died just days after receiving the first dose of a genetically engineered virus meant to combat his hereditary liver disease, had been ineligible to participate in the trial. The FDA also contended the researchers failed to notify the agency of previous, serious adverse effects of the treatment in other volunteers.” http://www.stanford.edu/dept/news/report/news/february21/policies-221.html 2) Genetically Engineered Food a. “When expert panels are convened to direct government policy, their recommendations may appear to be biased if the researchers have financial or organizational ties to industries that may benefit from a change in the rules. … a recent report from the National Academies indicating that genetically engineered food is safe to eat has been controversial because many of its panel members had ties to biotechnology companies.” http://www.stanford.edu/dept/news/report/news/february21/policies-221.html 3) HHS Secretary Shalala Initiatives: May 2000 http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2000pres/20000523.html a. The actions taken by HHS focused on expanding education and training for all clinical investigators and IRB members and staff; enhancing the informed consent process and ensuring more vigilant monitoring and oversight; ensuring that researchers understand and comply with federal conflict of interest regulations; and pursuing efforts to provide the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) with additional enforcement tools to enhance its oversight role. b. Education and Training. HHS will undertake an aggressive effort to improve the education and training of clinical investigators, IRB members, and associated IRB and institutional staff. NIH, FDA and the Office for Protection from Research Risks (OPRR) will work closely together to ensure that all clinical investigators, research administrators, IRB members and IRB staff receive appropriate research bioethics training and human subjects research training. Such training will be a requirement of all clinical investigators receiving NIH funds and will be a condition of the NIH grant award process and of the OPRR assurance process. c. Informed Consent. NIH and FDA will issue specific guidance on informed consent, clarifying that research institutions and sponsors are expected to audit records for evidence of compliance with informed consent requirements. For particularly risky or complex clinical trials, IRBs will be expected to take additional measures, which, for example, could include third-party observation of the informed consent process. The guidance will also reassert the obligation of investigators to reconfirm informed consent of participants upon the occurrence of any significant trial-related event that may affect a subject's willingness to participate in the trial. National Association of College and University Attorneys 7 d. Improved Monitoring. NIH will now require investigators conducting smaller-scale early clinical trials (Phase I and Phase II) to submit clinical trial monitoring plans to the NIH at the time of grant application, and will expect investigators to share these plans with IRBs. The NIH already requires investigators to have such plans and they also require large scale (Phase III) trials to have Data and Safety Monitoring Boards (DSMBs). For research on medical products intended to be marketed, FDA will also issue guidelines for DSMBs that will delineate the relationship between DSMBs and IRBs, and define when DSMBs should be required, when they should be independent, their responsibilities, confidentiality issues, operational issues and qualified membership. e. Conflict of Interest. NIH will issue additional guidance to clarify its regulations regarding conflict of interest, which will apply to all NIH-funded research. HHS is planning further discussions to find new ways to manage conflicts of interest so that research subjects are appropriately informed, and to further ensure that research results are analyzed and presented objectively. In addition, these public discussions will focus on clarifying and enhancing the informed consent process. Based on these public forums, NIH and FDA will work together to develop new policies for the broader biomedical research community, which will require, for example, that any researcher’s financial interest in a clinical trial be disclosed to potential participants. f. Civil Monetary Penalties. HHS will pursue legislation to enable FDA to levy civil monetary penalties for violations of informed consent and other important research practices-up to $250,000 per clinical investigator and up to $1 million per research institution. While FDA can currently issue warning letters or impose regulatory sanctions that halt research until problems are rectified, financial penalties will give the agency additional tools to sanction research institutions, sponsors and researchers who do not follow federal guidelines. As an interim step, NIH, OPRR and FDA will work more closely together to enforce and target existing penalties. 4) August 2000: HHS Conference on Human Subject Protection and Financial Conflict of Interest (http://ohrp.osophs.dhhs.gov/coi/8-16.htm#Koski) a. There was a strong sense that the human research review boards cannot be the sole implementer of the protections against conflicts of interest. b. There are certain points in the research process where an unavoidable conflict of interest is most likely to produce a negative impact: (i) The level of the direct interaction between the investigator and the research subject that the greatest potential for doing harms exists e.g. obtaining informed consent. (ii) During the analysis and interpretation of data, it is important to identify these hot spots so that there can be focused guidances and policies to assist the IRB on implementing appropriate provisions to minimize risks and optimize benefits. c. Conclusion at that meeting: there is the need to be sure that the policies and the protections are up to the task of meeting the goal of protecting the individual research subjects and to do so in such a way that the successful process of biomedical research does not come to a complete halt. 5) January 2001: OHRP Draft Interim Guidance a. Key Points Made in this Guidance (not yet a regulation): (i) HHS is offering a guidance to assist Institutions, Clinical Investigators, and IRB’s in their deliberations concerning potential and real conflicts of interest, and to facilitate disclosure, where appropriate, in consent forms. (OHRP Draft Interim Guidance, January 10, 2001 [following the August 2000 HHS conference on Human Subject Protection and Financial Conflict of Interest]. National Association of College and University Attorneys 8 (ii) Clear demonstration by sponsors, institutions and investigators to potential subjects that conflicts are being eliminated when possible and effectively managed when they cannot be eliminated, can help to develop a stronger bond of trust that can actually facilitate enrollment and the conduct of research. (iii) A focus on institutional conflicts of interest: While institutions clearly need to have policies and procedures for managing conflicts of interest among their employees, they should not lose sight of the need to manage their own conflicts of interest as well. Increasingly, academic institutions and corporate entities are entering into agreements that are mutually beneficial, and which may also bring the institution's interests into direct conflict with those of research participants. Any financial relationships that the institution has with the commercial sponsor of a study should be documented and the specific relationships submitted to the Chair/Staff of the IRB as described above. Items to be identified include: any equity interest in the commercial sponsor; any “up front” payments to the Institution beyond those payments directly applicable to carrying out a particular protocol; any funds given to the Institution (or an entity within the Institution, e.g. an Institute); any equity ownership in the commercial sponsor that was transferred to the Institution, including the percentage ownership of any patents related to articles under study in the protocol; any royalties; any licenses granted to the commercial sponsor by the Institution; whether or not the Institution stands to gain financially if the study shows the “article” to be successful for its proposed use. (iv) Clinical Investigators should consider the potential effect that having a financial relationship of any kind with a commercial sponsor of a study might have on his or her conduct of a clinical trial or interactions with research subjects. All aspects and types of relationships need to be considered, including commitments of financial support unrelated to the study in question, financial incentives, serving as a paid consultant or speaker on behalf of a commercial sponsor, non-monetary inducements or rewards to investigators or their family members. (v) Any agreements between Investigators and a sponsor should be reviewed by the Institution’s Conflict of Interest Committee or equivalent body. It is desirable to avoid conflicts of interest whenever possible. If a potential conflict cannot be eliminated, the committee’s determination of how the potential conflict is to be managed/reduced should be shared with the IRB for consideration during its discussion of the protocol. (vi) The IRB Chair should ask the IRB members about whether they have any potential financial conflict of interest related to any of the protocols that the IRB is about to consider. The IRB should have clear procedures for recusal of IRB members, including the Chair, from deliberating/voting on all protocols for which there is a potential or actual financial conflict of interest. Many IRBs remind their members of these policies at the outset of each meeting and incorporate this reminder in the minutes of the meeting. The IRB minutes should also specifically reflect such recusals as they occur during meetings. (vii) The IRB Policy and Procedures Manual should contain Institutional/ IRB Financial Conflict of Interest/financial relationship policies. Additionally, the manual should contain references to Conflict of Interest medical literature and the HHS August 2000 conference website (OHRP) where PHS/FDA policies, requirements, guidelines, and guidance may be found. http://ohrp.osophs.dhhs.gov/coi/index.htm National Association of College and University Attorneys 9 (viii) When the Institutional official or Conflict of Interest Committee or equivalent determines that a Clinical Investigator has a potential conflict of interest that cannot be eliminated, and must be reduced or managed in some way, IRBs should consider not only what modifications might need to be made to the protocol or Consent, but other approaches as appropriate. To assist, the IRB might wish to consider the answers to the following questions in its deliberations: (1) Who is the sponsor? (2) Who designed the clinical trial? (3) Who will analyze the safety and efficacy data? (4) Is there a Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB)? (5) What are the financial relationships between the Clinical Investigator and the commercial sponsor? (6) Is there any compensation that is affected by the study outcome? (7) Does the Investigator have any proprietary interests in the product including patents, trademarks, copyrights, and licensing agreements? (8) Does the Investigator have equity interest in the company? (9) Does the Investigator receive significant payments of other sorts? (e.g. grants, compensation in the form of equipment, retainers for ongoing consultation, and honoraria) (10) What are the specific arrangements for payment? (11) Where does the payment go? To the Institution? To the Investigator? (12) What is the payment per participant? Are there other arrangements? (ix) IRBs should consider the specific mechanisms proposed to minimize the potential adverse consequences of the conflict in an effort to protect the interests of the research subjects. In general, if there are any financial conflict of interest issues on the part of the Clinical Investigator, he or she should not be directly engaged in aspects of the trial that could be influenced inappropriately by that conflict. These could include: the design of the trial, monitoring the trial, obtaining the informed consent, adverse event reporting, or analyzing the data. In all cases, good judgment, openness of process and reliance upon objective, third party oversight can effectively minimize the potential for harm to subjects and safeguard the integrity of the research. IRBs (institutionally based and non-institutionally based) should consider including in the consent document the source of funding and funding arrangements for performing the IRB review of that protocol. (x) Additional Thoughts: (1) The Institutional official may wish to distribute copies of letters relating to the management of significant financial conflict of interest that are submitted to PHS or FDA Grants Management by the Institution to the IRB, when appropriate. (2) The Institution should collect and review information from IRB staff, Chair, and all members on their financial interests with commercial sponsors, at least on an annual basis. Institutional policies and procedures should include specific guidance for all of the above regarding potential and actual financial conflicts and their management. 6) September 2002: NIH convened a meeting to reassess individual and institutional conflicts of interest. There is the potential for revisions to individual Conflict of Interest regulations and it is anticipated that Institutional Conflict of Interest regulations will be proposed in the near future. 7) AAMC Task Force Issues Report on Institutional Conflicts of Interest in Research http://www.aamc.org/coitf. National Association of College and University Attorneys 10 a. September 2002: The AAMC Issued "Protecting Subjects, Preserving Trust, Promoting Progress II," which proposes a framework for the oversight of institutional financial conflicts of interest that conduct human subjects research. b. The Task Force's key recommendation is that institutions separate their financial and research management functions as cleanly as possible. According to the report, the welfare of human subjects and the objectivity of the research could be -- or reasonably appear to be -- compromised whenever an institution holds a significant financial interest that might be affected by the research outcome. The report further recommends that, under some circumstances, human subjects research not be conducted at a conflicted institution, unless compelling circumstances warrant. 8) NSF Regulations: “Conflict of Interest Policies” a. The NSF regulations are almost identical to those of the NIH. Both have the same effective date, October 1, 1995. Therefore, I will not repeat the requirements but will highlight the two significant differences: (i) The NSF regulations exempt institutions which employ fifty (50) persons or less; and (ii) The requirement to report to PHS is not consistent with the NSF, which requires reporting only if the institution is unable to satisfactorily manage a conflict of interest. ALL conflicting interests must be reported to the PHS. b. It is worth noting that the HHS and NSF have worked collaboratively and continue to work together to develop common regulations, guidances and a set of questions and answers that may be found at http://grants2.nih.gov/grants/policy/coifaq.htm. IV) IMPLEMENTATION OF A CONFLICT OF INTEREST POLICY AND PROCESS A) Start with a premise: Conflicts of Interest are neither unusual nor bad – just a fact of life that requires attention. B) Pressures to Recognize 1) No other employer allows and encourages its employees to participate in “outside business activities;” 2) The private sector wants and needs the participation of university researchers, resulting in conflicts of interest, time and commitment; 3) Economic development objectives stimulate and encourage entrepreneurship on the part of academicians, but present challenges: a. Ownership of intellectual property; b. Risks of equity ownership (by investors or institutions); 4) Engaging in business activities in the academic enterprise blurs the margins of propriety; 5) Academia has not always kept its house in order (e.g., misuse of graduate students, university property for personal gain); 6) These are major issues with much to gain and even more to lose; 7) A new spotlight mandates that we pay attention. C) Policy Questions to Answer Before Drafting a Policy 1) How to reconcile various approaches (Note: personalities may drive a result (“bad facts make bad law”)): a. strictly prohibitive, b. completely permissive, c. general rules with exceptions? 2) How does the institution want to relate to industry? a. Grantee of sponsored research b. IRB considerations c. Consulting policies and intellectual property National Association of College and University Attorneys 11 3) Process: What should the process for implementation of the policy include: a. Should there be a Committee on Conflicts of Interest (i) Will the Committee be a decision-making body? (ii) Will the Committee be only an advisory body? If so, advisory to whom? b. Who will be responsible for determining and monitoring management techniques designed to manage identified conflicts of interest? c. How can the institution assure consistency in the application of its Conflict of Interest Policy: (i) Different schools: different decision makers (ii) Different circumstance (investigator, amount of money, sponsoring organization) may be subject to different decisions. d. Who will provide the education? (i) To whom? (ii) By whom? (iii) Necessary updates. e. How to play “Catch up:” how to address existing conflict of interest situations (so not to paralyze the institution and its investigators or, by pocket veto, force investigators to forego opportunities) while attempting to create a whole new set of rules for the future. (The train has already left the station…) 4) Recommendations for Policy Drafting a. An “Introduction” or “Purpose” section indicating the intent of the policy is to promote objectivity in research by establishing standards to ensure there is no reasonable expectation that the design, conduct, or reporting of research funded under grants or cooperative agreements will be biased by any conflicting financial interest of an investigator. (Title 45 CFR Part 50, Subpart F) b. State an effective date for the policy, including dates for all revisions. c. Identify a contact point within the institution who investigators and others may contact for questions and discussion. d. Specify that the policy applies to investigators participating in PHS/NSF (and any other included by the institution) research, including subgrantee/contractor/collaborating Investigators, but excluding applications for Phase I support under the SBIR and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) programs. e. Define key terms, such as Investigator, PHS Awarding Component, Research, Significant Financial Interest, and SBIR. f. Specify the investigator’s reporting responsibilities to the institution (what needs to be reported and to whom). g. Identify an institutional official(s) to solicit and review financial disclosure statements from investigators submitted annually or as new reportable interests are obtained. h. Provide guidelines and examples for both the investigators and the designated official(s) to identify conflicting interests. i. Specify that records of all financial disclosures and all actions taken by the institution will be maintained for at least three years from the date of submission of the final expenditures report. j. Identify the enforcement mechanisms available to the institution and specify the sanctions where appropriate. k. Provide a “Reporting” section that specifies what the institution must report: l. Specify that the institution: (i) agrees to make conflict information available, upon request, to HHS; National Association of College and University Attorneys 12 (ii) will, if the investigator has biased the research, promptly notify the awarding component of the corrective action taken or to be taken. 5) Real Life Statistics Relating to Conflict of Interest Policies http://grants1.nih.gov/grants/policy/coi/nih_review.htm) a. The NIH studied over 100 conflicts of interest policies to “develop a broad view of how these policies are implemented by an array of institutions” and found the following aspects of policies that would benefit from clarification: (1) 96 percent did not mention the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program in the policy document(s); (2) 86 percent did not define “Research;” (3) 52 percent did not identify the applicable PHS regulation; (4) 47 percent did not address “records management;” (5) 74 percent did not state agreement to make conflict information available to HHS; (6) 45 percent did not require the reporting of the conflict to the PHS awarding component that issued the award; (7) 54 percent did not mention compliance regarding subgrantees/contractors/collaborators; (8) 76 percent did not require notification to the awarding component within 60 days regarding conflicting interest identified subsequent to initial report; (9) 68 percent did not indicate that if the investigator has biased the research, the institution would promptly notify the awarding component of corrective action taken or to be taken; (10) 87 percent did not state that if HHS determines that a PHS-funded project to evaluate a drug, medical device or treatment was conducted by an investigator with a conflict that was not disclosed or managed, the institution must require investigators to disclose the conflict in each public presentation of the results of the research. 6) Suggestions for Implementation (http://grants1.nih.gov/grants/policy/coi/nih_review.htm) a. Addresses directly the mandate of the PHS regulations by developing the Conflict of Interest Policy as a complete, self-contained document with citations and web links to supporting policies, procedures, and federal and state regulations. It is implementation of the management processes that presents the greatest challenge to institutions. Joan and I will discuss, in Part III of our presentation, various approaches either recommended or taken by different organizations and institutions. PART III: IMPLEMENTATION OF CONFLICT OF INTEREST POLICIES AND PROCESSES: CASE STUDIES I) UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER Drafting an “appropriate written and enforced conflict of interest policy” can be challenging for a university. However, the even greater challenge is in the implementation of the processes. (Moses: Compliance Cartoon) A) Issues to Balance National Association of College and University Attorneys 13 1) The University of Rochester encourages researcher/faculty members to engage in outside activities: a. Consulting b. Science Advisory Boards c. Technology Transfer activities 2) As second largest employer in the Rochester community, there has been much encouragement for faculty entrepreneurship…which raised issues of intellectual property ownership, conflicts of commitment and conflicts of interest relating to faculty equity and start-up companies. 3) The business community wanted the University of Rochester researcher’s participation – but on its terms 4) The University of Rochester and its researchers rely heavily on private sector support of research B) University of Rochester’s Policy (A work in progress…) 1) The University of Rochester has had a conflict of interest policy, as part of our Faculty Handbook, since before NIH/NSF regulations took effect. However, this policy had been implemented decentrally – and inconsistently – by the various schools/centers and institutes. Also, policy and processes did not provide the flexibility the changing environment required. (Truck: Divided Cartoon) 2) In the late 1990’s the University revised its Intellectual Property/Technology Transfer policy, which imposed a new requirement: a “Conflict of Interest Committee.” 3) The University Committee: a. Challenges (i) Who should sit on the Conflict of Interest Committee? (1) Institutional/administrative representatives vs. researcher/entrepreneur representatives; ultimately, the University of Rochester’s Committee added faculty/researcher representation (2) Medical center representatives vs. undergraduate college departments representatives (3) Conflict of Interest Committee comprised of: Provost, Associate Provost, General Counsel, Associate Counsel, Director of University Technology Transfer, Director of Medical Center Technology Transfer, Director of the Research Subjects Review Board, Director of the Office of Research and Project Administration, Chief Operating Officer for the Medical Center, Dean of Research and Graduate Studies for the University, Senior Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, Executive Director for Government Relations, two Professors from the University, and two Professors from the Medical Center. b. Review and revise the Conflict of Interest Policy: As part of that process, refine and redefine what our institutional approach would be: reducing, managing and/or eliminating conflicts of interest. There was much debate regarding: if/when to prohibit. (i) Goal: The goal of the policy is to avoid or to manage situations that call into question the credibility and objectivity of the research and findings by the faculty member. An additional goal is to promote the best interest of students and others whose work depends on faculty direction. The UR is an institution of trust; faculty must respect this principle and conduct their affairs in ways that do not compromise the integrity of the University. In addition the University recognizes that even the perception that faculty have financial interests in the outcome of their research can call in to question the credibility and objectivity of this research. (1) Disclosure is a key focus National Association of College and University Attorneys 14 (2) All “investigators” (as defined by the federal regulations) as well as the Office of Technology Transfer, Office of Research and Project Administration and Senior Administrators are required to complete disclosure forms. c. Define the process(es) by which the Conflict of Interest policy would be implemented. d. Should clinical research conflicts of interest be treated differently than other conflicts of interest? (i) Some favored absolute prohibition (ii) Others favored case-by-case management (iii) Decision: As a general rule, prohibit conflicts of interest, but allow for exceptions. The University of Rochester policy states: (1) An individual who holds a significant financial interest in clinical trial research may not conduct such research unless he or she can show compelling reasons to do so. This prohibition extends to all who report (directly or indirectly) to the financially conflicted individual. The determination of whether or not there exist compelling circumstances for the financially conflicted individual to conduct the trial will be made by the Dean after examining the investigator’s written justification, and seeking the advice of the department chair(s) as appropriate. In the event of compelling circumstances, an individual holding a significant financial interest in clinical trials research may be permitted to remain involved in the research. Whether the circumstances are deemed compelling will depend in each case upon the nature of the science, the nature of the interest, how closely the interest is related to the research, and the degree to which the interest may be affected by the research (e.g., the phase of the trial). However, when the equity interest is in a start-up company that manufactures the investigational product, participation in anything other than a consulting role is prohibited. (2) If the Dean determines that the circumstances are compelling, a conflicted faculty member seeking involvement in a clinical trial must devise a conflict management plan to be approved by the Dean in advance of initiating the trial. In all clinical trials with a conflicted faculty member, the conflict management plan must include at a minimum: 1) a full disclosure of the interest (to research subjects and others as appropriate), and; 2) requirement that informed consent be obtained by a clinician with no financial ties to the research. Conflicted investigators may not serve as the project's principal investigator. Rather, another principal investigator must be identified to oversee the administration of the trial, including enrollment of subjects, overseeing the subject consent process, testing the drug or device, and analysis of results. The appointed investigator must be qualified to administer the study protocol, and must not be junior within the department to the financially involved investigator. e. Integration with Consulting Policy: Key issues: (i) Intellectual Property ownership (ii) Insufficient resources to review consulting contracts and advise faculty; plus, question of whether even appropriate (iii) Scope of Consulting: Some issues addressed: e.g. Specific activities that require explicit prior written approval of the department chair and Dean include, but are not limited to, serving as a PI on behalf of another institution or entity; serving in a significant managerial role of a for-profit entity; and assuming a board position in a for-profit company in which he or she has a significant financial interest. National Association of College and University Attorneys 15 f. What are respective roles of Conflict of Interest Committee, Deans, and Provost in decision-making? Decision: Deans and Provost are decision-makers; Conflict of Interest Committee: advisory to them. (i) The Deans of each School/College has the authority to decide how to reduce, manage or eliminate the conflict of interest but must report his/her decision (along with an explanation of the reasons for the decision) to the Conflict of Interest Committee so that the “case law” may develop. (1) The Policy imposes time limits for a Dean to respond, including time limits for approval of a management plan if there is one. (2) The Dean’s decision may be appealed through the usual faculty grievance procedures of the Faculty Handbook. (ii) The Deans, faculty and other University of Rochester officials encountering conflict situations may seek the advice of the Conflict of Interest Committee. g. How to create a neutral/non-judgmental environment about something as loaded as the term “Conflicts of Interest” (i) To maintain credibility with entrepreneur/faculty; (ii) To maintain focus on objective: encourage/increase sponsored research while assuring its scientific objectivity and the credibility of the researchers while also protecting and enhancing the reputations of the University and its researchers; and (iii) To protect human subjects: most importantly (iv) Decision: Management, rather than reduction or elimination of conflicts of interest was determined to be the guiding principle. 4) Requirements in addition to those contained in the federal regulations: a. Faculty are prohibited from involving students, whom he or she directly supervises or advises in a University graduate program, in business activities outside the University in which the faculty has a significant financial interest and/or officer or director role, unless approved by the Dean. If the Dean approves such involvement, the faculty advisor, student, and Dean must agree in writing to a conflict management plan. The plan must include, at a minimum: i) ongoing oversight by a faculty committee (e.g., the thesis committee), ii) a guarantee that financial support will not decline before completion of the degree requirements as long as the committee judges the student's progress to be acceptable, and iii) a guarantee that a suitable advisor will be appointed to replace the conflicted advisor if necessary; b. Faculty are prohibited from assigning students, staff or postdoctoral scholars tasks, within the University program, for purposes of potential or real financial gain of the faculty member rather than the advancement of the scholarly field or the students' educational needs; c. Investigators may not hold an equity interest in any company that when aggregated for the individual and family members meets both of the following tests, (i) is less than $10,000 in value as determined through reference to public prices or other reasonable measures of fair market value, and (ii) is less than a one- percent ownership interest. d. The Conflict of Interest Policy applies to ALL research, not just federally-funded research. e. The Conflict of Interest Policy was revised to include University-wide Conflict of Interest Processes. f. The Conflict of Interest Policy empowered the Conflict of Interest Committee to evaluate Conflict of Interest cases, upon request as well as upon its own initiative. National Association of College and University Attorneys 16 g. The Conflict of Interest Policy authorized the Conflict of Interest Committee to recommend to the Provost, management actions to address conflicts of interest. h. The Conflict of Interest Policy charges the Conflict of Interest Committee to compile and maintain a listing of all conflict of interest situations brought to the attention of the Conflicts of Interest Committee in order to develop “case law” (consistent rulings). i. Conflict of Interest Decision-Making Process: Researcher/Investigator/Faculty with Conflict of Interest Chair Dean Conflict of Interest Committee for advice Provost. Management plans are variable, per the situation. The Conflict of Interest Committee, Deans and Provost work with faculty and the departments to establish a workable management plan. 5) Work in Progress: Issues under Discussion a. What to do with University/institutional conflicts? Deferred: Awaiting NIH guidance. b. Integration of the Conflicts of Interest, Consulting and Intellectual Property/Technology Transfer (ownership of Intellectual Property issues) policies. c. Processes (i) Who will educate faculty regarding conflicts of interest? (ii) Who will review disclosure forms and bring questions to the attention of the deans for decision? 6) Hoped-for Advantages of the Revised Policy and Process a. Clearer expectations for faculty b. Clearer expectations by faculty c. More knowledgeable/experienced conflict of interest decision-makers and advisors d. Greater consistency across campus e. Broader historical perspective and underpinnings f. Greater credibility among faculty g. More realistic approach and greater compliance through a philosophy of management vs. prohibition h. Clarification regarding use of graduate students: generally prohibited i. Greater protection and preservation of University and researcher reputations and credibility j. Clarification regarding and clearer protection of human subjects C) Summary 1) Institutional conflict of interest policies continue to evolve, as both the science (e.g. gene therapy, cloning) and the opportunities for technology transfer continue to evolve. 2) The challenge will be maintaining institutional commitment, focus, coordination, and integration to keep pace with the evolution. National Association of College and University Attorneys 17