The Life and Legacy of Mary Livermore

advertisement

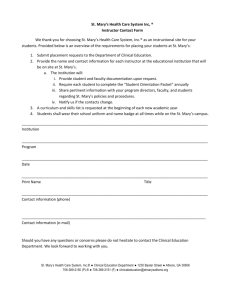

An Abiding Faith in Human Destiny: The Life and Legacy of Mary Livermore Rev. Tim Temerson UU Church of Akron January 22, 2012 Today I’m going to tell you an amazing story - a true story about one of the most extraordinary women in American history and in the history of Unitarian Universalism. Mary Livermore doesn’t get much coverage in today’s history books and I’m guessing many of you have never heard of her. But during the second half the 19th century, Mary Livermore was one of the most important and influential voices in American public life. She was a famed lecturer and public speaker, a gifted writer and journalist, a courageous and committed social activist, and a founder and organizer of the United States Sanitary Commission, which was the precursor to the American Red Cross. And finally, Mary Livermore was one of the most important leaders and voices in American Universalism – a voice that still speaks powerfully and passionately to our time and our own Unitarian Universalist faith. Now I must tell you that in addition to all the wonderful things she accomplished in her lifetime, I chose Mary Livermore as the subject of today’s service because I feel a spiritual kinship to her. You see, having grown up in a religious tradition that left her feeling wounded and very uncertain, Mary’s life was transformed when, as a young woman, out for a stroll on a Christmas Eve, she walked into a Universalist church in a small village on the southeastern coast of Massachusetts called Duxbury. Well, about a dozen years ago, my life was transformed when I set foot in a Unitarian Universalist congregation in that same small town - Duxbury, Massachusetts. I’m going to spend a good of time talking about Mary Livermore experience that Christmas Eve because I believe it is the key to understanding her extraordinary life. Universalism opened Mary’s heart and warmed her spirit. It made her feel welcome and valued by God and by the universe. From that moment until the day she died, Mary lived from a place of great hope, great joy, and great determination to do all that she could to build a world of love and justice and peace for all people. The story of Mary’s awakening to Universalism begins in Boston where she was born in 1820. Religion and religious concerns dominated Mary’s childhood and youth. Her father, Timothy Rice believed wholeheartedly in the doctrines of Calvinism, which teach that a God of judgment and punishment arbitrarily chooses those who will be saved (known as the elect) while relegating the vast majority of humankind to eternal damnation. Listen to Mary’s description of the impact Calvinism had on her father and her family. “My father’s nature was so large and generous that his heart was continually at war with his creed. Nature had made him an optimist, while his creed transformed him into a pessimist. He mourned and wept while he taught that the doom of endless perdition hung over the majority of the human race. He never escaped this early belief and so lost the joy of life which nature had designed for him.” Mary’s religious upbringing led her to lose the joy of life as well. She saw a world filled with beauty and belonged to a loving family. And yet she was told time and again that God would most likely consign her and her loved ones to hell. Mary experienced a deep-seated crisis of faith when a beloved younger sister died. She was terrified that her sister was going to punished for eternity and even proposed ending her own life so that she could take her sister’s place in hell. The loss of her sister threw young Mary Rice into a terrible spiritual crisis. What was the point of living, of loving, of caring for others and the world if the universe is governed by a deity who would condemn a sweet, young child to eternal punishment and torment? After Mary completed her education, she accepted an offer to teach the children of a plantation owner in Virginia. Although she was treated well and enjoyed her life as a teacher, I think it’s safe to say that Mary’s experience on that plantation, and especially her encounter with the horror and brutality of slavery, deepened her crisis of faith. One day while out for a walk on the plantation, Mary witnessed the brutal whipping a slave named Matt. She had never experienced such violence and such brutality. In many ways, the overseer who wielded that whip reminded Mary of the God of her childhood. And I think it safe to say that Mary’s encounter with slavery and especially with the whipping of Matt led her to lose faith not only in the God of her childhood but in the promise and possibilities of life in the here and now. She had been raised on a God who was harsh and vindictive, and she experienced that same vindictiveness when she witnessed the whipping of Matt. Perhaps Calvinism’s view of God and humanity was right after all – the world was corrupt, evil, sinful, and not worth saving. Maybe, just maybe, God’s anger was justified. Mary Rice returned from Virginia with a heart and a spirit that were heavy. An offer to teach at a private academy in the coastal town of Duxbury soon gave her a new opportunity and a new beginning. But as much as she enjoyed her new life, she could not find a way out of the spiritual darkness that enveloped her. As Mary walked along one of Duxbury’s streets on Christmas Eve, she heard the faint sound of beautiful music and singing. The beautiful music was coming from a church – the small Universalist church in Duxbury. Mary had heard of Universalism but didn’t know much about it except that it was (and doesn’t this sound familiar) strange, heretical, not really a religion, and certainly to be avoided. In spite of her misgivings, Mary was irresistibly drawn to that small church. Her autobiography has a wonderful illustration of this moment which is up on the screen. The way Mary describes it, she stood by the door, hesitating to go in, uncertain of what she might encounter, and fearful of having her deep religious wounds opened further. Mary overcame her fear and walked into that church. And what she heard and experienced that night changed her life. She heard music and prayers and a sermon that approached religion and life from a perspective she hadn’t thought possible. Where she had once only heard judgment, now she only heard love. Where she had once only heard fear, now she only heard joy. And where she had once only heard of a God who is judgmental and punishing, now she heard only of a God who is a loving parent, a good shepherd, a compassionate friend who welcomes everyone, everyone into the divine embrace. That night, that sermon, that Christmas Eve service changed everything for Mary Livermore. As she describes it in her memoir, “A great peace came over me. A pulsation of love for all the world throbbed through my being. As I glanced over the listening congregation, I wished I might shake hands with every person present.” What a beautiful description, a beautiful testament to the power of a religion and a community steeped in love to heal a broken heart and to save a human life. Universalism opened Mary Livermore’s heart and mind to the promise and possibilities of life. If God was a God of love rather than punishment, then there was hope for humankind. Human beings were not inherently sinful but were, instead, like lost children of a loving God who could find their way and transform themselves and the world into an oasis of love and compassion for all. Mary Livermore went into that church convinced that life was ultimately hopeless and joyless. She came out, as the title of today’s service says, “with an abiding faith in human destiny.” And by the way, that night in the church in Duxbury changed Mary Livermore’s life in another glorious and blessed way. You see, the service Mary Rice attended that night was led by a young minister named Daniel Livermore. And yes, Mary and Daniel were eventually married and shared a 50 plus year marriage, partnership, and friendship that brought great joy and great meaning to their lives. After they were married, ministry took Mary and Daniel to several small churches and communities in New England. But they soon realized that the life of parish ministry just wasn’t for them. They decided instead to try their hands at writing and journalism. Daniel purchased a small Universalist newspaper in Chicago and Mary soon became his most important and famous writer. Mary and Daniel also turned their attention to social reform, writing and organizing on behalf of temperance, the abolition of slavery, and the rights of women. As I mentioned earlier, Mary’s fame grew steadily and she became an important public figure. Her work with the US Sanitary Commission was so invaluable to the Union during the Civil War that President Abraham Lincoln himself presented with an original copy of the Emancipation Proclamation. And after the war, Mary continued her writing, her social activism, and embarked on what became her life’s work – lecturing about a variety of subjects, ranging from social issues like peace and women’s rights to literature, history, and just about everything under the sun. Earlier you heard an excerpt from her most popular and famous lecture “What Shall We do With Our Daughters,” which remains one of the great statements on behalf of women’s rights in American history and which Mary delivered over 800 times during her public speaking career. Mary Livermore didn’t live to see ultimate victory in many of the struggles she had worked so tirelessly to achieve. Mary died on 1905, 15 years before the 19th amendment, which gave women the right to vote, was ratified. But in many ways, I think the struggle at the heart of Mary Livermore’s life had already been won. Not the struggle for equal rights or for fair and just treatment for the entire human family. That struggle goes on. But what had been won in her heart and in her life was a deep and abiding faith that the struggle is worth making, that history is ultimately on the side of love and justice, and that humankind is not destined for punishment or for vengeance, but rather that we are created, that we are called, that we are destined to live in a world that is fair, that is just, that is loving, and that is at peace. That’s the world Mary Livermore struggled for and that’s world each and every one of us, the Unitarian Universalist heirs to her extraordinary example and legacy – that is the world we are called and that we are destined to build.