OUTLINE

I. Case Based

Introduction

Web Based Education Module 4: “Doc, I’m Tired and Have Little Energy”

FINAL DRAFT - CORE CONTENT

CONTENT

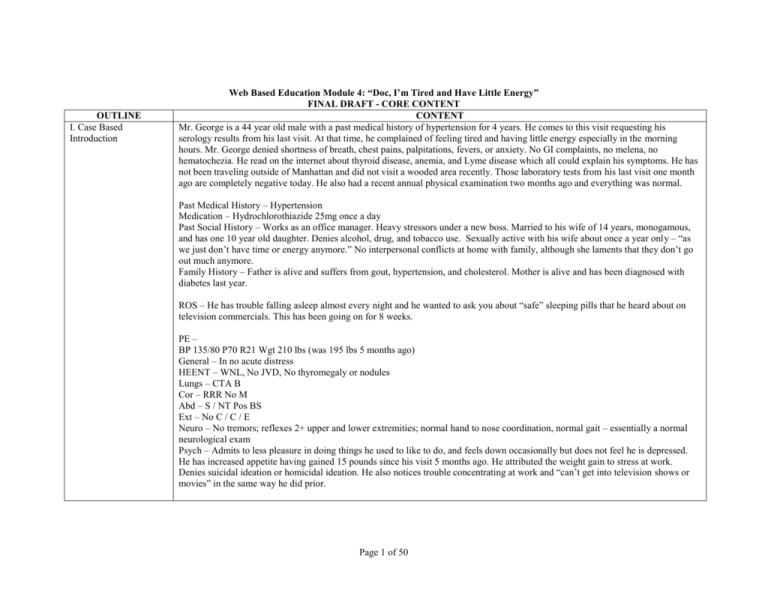

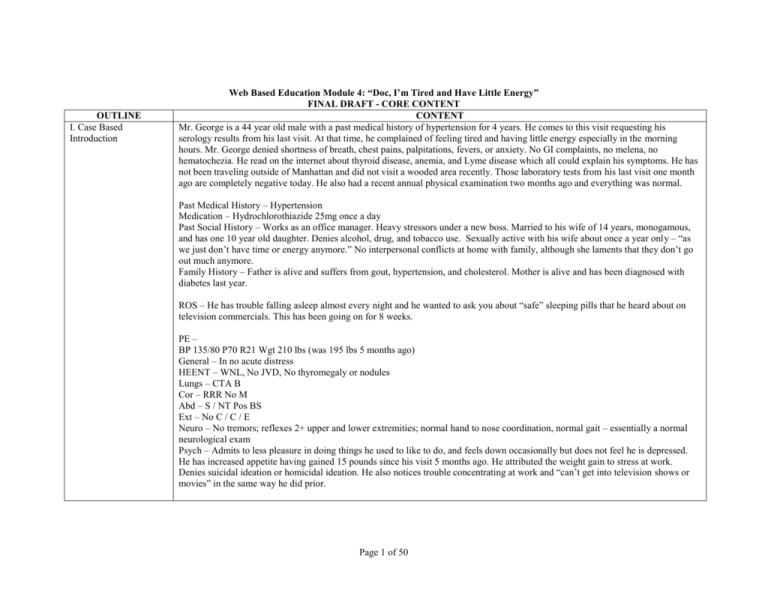

Mr. George is a 44 year old male with a past medical history of hypertension for 4 years. He comes to this visit requesting his

serology results from his last visit. At that time, he complained of feeling tired and having little energy especially in the morning

hours. Mr. George denied shortness of breath, chest pains, palpitations, fevers, or anxiety. No GI complaints, no melena, no

hematochezia. He read on the internet about thyroid disease, anemia, and Lyme disease which all could explain his symptoms. He has

not been traveling outside of Manhattan and did not visit a wooded area recently. Those laboratory tests from his last visit one month

ago are completely negative today. He also had a recent annual physical examination two months ago and everything was normal.

Past Medical History – Hypertension

Medication – Hydrochlorothiazide 25mg once a day

Past Social History – Works as an office manager. Heavy stressors under a new boss. Married to his wife of 14 years, monogamous,

and has one 10 year old daughter. Denies alcohol, drug, and tobacco use. Sexually active with his wife about once a year only – “as

we just don’t have time or energy anymore.” No interpersonal conflicts at home with family, although she laments that they don’t go

out much anymore.

Family History – Father is alive and suffers from gout, hypertension, and cholesterol. Mother is alive and has been diagnosed with

diabetes last year.

ROS – He has trouble falling asleep almost every night and he wanted to ask you about “safe” sleeping pills that he heard about on

television commercials. This has been going on for 8 weeks.

PE –

BP 135/80 P70 R21 Wgt 210 lbs (was 195 lbs 5 months ago)

General – In no acute distress

HEENT – WNL, No JVD, No thyromegaly or nodules

Lungs – CTA B

Cor – RRR No M

Abd – S / NT Pos BS

Ext – No C / C / E

Neuro – No tremors; reflexes 2+ upper and lower extremities; normal hand to nose coordination, normal gait – essentially a normal

neurological exam

Psych – Admits to less pleasure in doing things he used to like to do, and feels down occasionally but does not feel he is depressed.

He has increased appetite having gained 15 pounds since his visit 5 months ago. He attributed the weight gain to stress at work.

Denies suicidal ideation or homicidal ideation. He also notices trouble concentrating at work and “can’t get into television shows or

movies” in the same way he did prior.

Page 1 of 50

Labs:

Guaiacs Neg x 3

TSH 1.44 (WNL 0.34 – 4.25)

Chem 7 WNL

Hct 40

Lyme Titers Neg

Question 1) Mr. George feels tired and has little energy. His physical examination and lab work are negative. He completely denies

being depressed. Upon further questioning he does describe losing interest in activities he used to like to do, increased appetite and

weight gain, problems with concentration, and insomnia. At this point, Mr. George wants to know the next appropriate step in his

assessment and management. Of the following, which one is the most appropriate recommendation?

a)

b)

c)

d)

e)

f)

II. Facts About

Depression

Perform a whole body CT or MRI scan to look for an occult source

Recommend that Mr. George and his family go on a vacation

Consider testing for underlying neurological disease

Refer him to a gastroenterologist for a colonoscopy screen

Have Mr. George complete a standardized screening questionnaire for depression

Write him a prescription for sleeping medications

The correct answer is e. Mr. George has many classic signs and symptoms of depression (e.g., anhedonia, insomnia, weight

gain, etc.), and performing a standardized screening questionnaire for major depression is appropriate to assist in making the

diagnosis. Many people who suffer from depression do not report a depressed mood. Although some neurological diseases can

have depressive symptoms, major depression is much more common in the primary care setting and should be evaluated first. He

also has no neurological findings. A colonoscopy would not seem appropriate in a 44 year old man at this point without

gastrointestinal complaints, no findings of anemia, and weight gain. A whole body CT or MRI scan is not cost effective, and may

cause more physical and emotional harm than benefit. Insomnia may be a sentinel symptom of depression, and prescribing

sleeping medications without assessing the patient for depression would not be “best practice”. Although a vacation may be in

order for Mr. George and his family, it will not effectively treat an underlying depressive disorder.

Web Based Education Module 4: “The Diagnosis and Management of Depression in The Primary Care Setting”

Facts About Depression

Depression is one of the most common conditions seen by primary care physicians second only to hypertension. The point prevalence

in the outpatient primary care setting is between 4.8 – 8.6%, and the point prevalence in the inpatient setting is 14.6% Large scale

studies have suggested that 7 – 12% of men will suffer an episode of major depression at one point in their lives, while the percentage

for women is more on the order of 20 – 25%. Bipolar disorder is less common than depression (0.4% in men and 1.6% in women over

their lifetimes) but has no gender difference. Depression can begin in early adulthood, with a peak onset between ages 20 – 30. Over

Page 2 of 50

half the people who experience an episode of major depression are at risk for a relapse and recurrence (Cutler, J. Charon, R. 1999).

Depression costs the United States economy more than 43 million dollars every year in medical treatments and lost work productivity

(Kahn, 1999). Globally, depression accounts for 4.4% of the disease burden, which is similar to that of diarrheal diseases and ischemic

heart disease (Mann, 2003). 300 million people in the world suffer from depression with 18 million of them in the United States

(Harvard Press, 1996).

Depression has a high rate of morbidity and mortality when left untreated. Most patients do not necessarily complain of feeling

depressed, but rather that they have a lack of interest or pleasure in activities, may have somatic complaints, or vague unexplained

complaints. In one study, 69% of diagnosed depressed patients reported unexplained physical symptoms as their chief complaint

(NYCDOH, 2006). Unlike patients with depression in psychiatric inpatient or outpatient care settings, persons suffering from

depression in primary care settings often present as “undifferentiated” patients.

Depression is often undiagnosed and untreated, and even when it is diagnosed it is often under treated. Primary care physicians must

remain alert to effectively screen for depression in their patients. Barriers to effective screening include inadequate education and

training, limited coordination with mental health resources, time constraints, poor systematic follow up, and inadequate

reimbursement (NYCDOH, 2006). It is sometimes difficult for primary care providers to determine if a patient is depressed as

opposed to experiencing a normal response to the challenges of everyday life. Gender, age, culture, and language of the patient and

the physician may create further barriers. Furthermore, persons with mood disorders also may have enormous stigma associated with

being mentally ill – and may see it as a sign of weakness, fear the criticism of other people, or be concerned that they will be

institutionalized.

III. Goals and Objectives

Patients who suffer from diabetes, ischemic heart disease, stroke, or lung disorders that have concurrent depression have poorer

outcomes than those without depression. Depressed patients have a higher risk of death from heart disease, respiratory disorders,

stroke, accidents, and suicide (Mann, 2005). Fifteen percent of patients with severe mood disorders die from suicide. In one study

among older patients who committed suicide, 20% visited their primary care physician on the same day as their suicide (NYCDOH,

2006).

Educational Goal: Students will be able to demonstrate competencies in knowledge, skills, and attitudes of an effective clinician in

evaluating and caring for patients with depression and mood disorders in the primary care setting.

Medical Knowledge

The students will:

1. Apply the nationally recognized guidelines for screening and diagnosing depression and other mood disorders in patient care.

2. Apply the practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorders.

3. Identify appropriate elements of a suicide risk assessment and action plan.

Page 3 of 50

Patient Care

The students will:

1. Recognize the importance of effective detection and treatment of depression in adults.

2. Review the depressed mood algorithm and the DSM-IV to guide the differential diagnosis in the primary care setting.

3. Identify manic and hypomanic symptoms associated with bipolar disorder in depressed patients.

4. Formulate management plans for the longitudinal care of patients with depression.

5. Develop prevention plans, including health education and behavioral change strategies, for patients with depression.

Interpersonal and Communication Skills

The student will:

1. Explore relevant psychosocial and cultural issues that impact on care.

2. Provide effective education and counseling to patients with mood disorders and their families.

3. Demonstrate awareness of improved health care outcomes through effective communication and forming therapeutic

alliances with patients.

4. Discuss behaviors with patients, in an empathic, respectful and non judgmental manner.

Practice Based Learning

The student will:

1. Use information technology to access medical information and support self-education and clinical decision making.

2. Critically review the medical literature regarding new evidence based clinical trials and its implication on current treatment

guidelines of depression and mood disorders.

3. Use information technology to access patient and family education resources on depression.

Professionalism

The student will:

1. Demonstrate professionalism by completing this web module during the assigned period.

Systems Based Practice

The student will:

1. Identify which cases can be managed by the primary care physician and which should be referred for co-management with a

specialist.

2. Improve patient care outcomes through effective communication with other health care professionals, partnerships through

Page 4 of 50

IV. The Etiology of

Mood Disorders

community resources, and government agencies.

The Etiology of Mood Disorders

Neurotransmitters, genetics, and psychosocial stressors all seem to play a part in mood disorders.

The same depressed patient may have variable clinical symptoms from one major depressive episode to another. Despite this

variability, major depression may have the same underlying cause. The variable presentations may be due to differing patterns in

neurotransmitter abnormalities. Deficiencies in serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine, GABA, and peptide neurotransmitters

(somastatin, thyroid-related hormones, and brain derived neurotrophic factors) have all been hypothesized as contributing to

depression. Over activity in other neurotransmitters including substance P, and acetylcholine, and elevated serum cortisol (with lack

of diurnal variation) has also been proposed to contribute to depression.

Although no specific genes that affect neurotransmitters or hormones have been identified, both depression and bipolar disorder are

clearly inheritable. The first degree relatives of a patient with recurrent major depression have a 1.5 – 3 times higher risk of depression

themselves as compared to the general population. 27% of children with one parent with a mood disorder will develop a mood

disorder themselves, and that increases to 50 – 75% if both parents are affected. First degree relatives of patients with bipolar disorder

have an estimated 12% lifetime prevalence of bipolar disorder, which is 10 times higher than the general population (Cutler, J.

Charon, R. 1999). Genetic predisposition is not enough to result in a patient with a mood disorder, however. Identical twins have

incomplete concordance in regards to depression. Depression also occurs in patients with no family history of mood disorders, which

may infer that they have another acquired biological deficiency such as a viral insult, genetic or perinatal insult, or vascular brain

disease.

Psychosocial stressors in combination with a genetic predisposition have been postulated to alter the size of neurons, neuronal

function, repair capabilities, and production of new neurons. Elevated cortisol in some depressed patients may reduce hippocampus

volume, especially if their depression has not been treated in some time. Brain imagery has also noted some altered structures, which

suggest some changes in neurocircuitry. Psychosocial theories suggest that experiences of “loss” in certain vulnerable individuals may

cause depression, either through trauma, parental loss, loss of love from others, or loss of self-esteem.

Page 5 of 50

“On the Threshold of Eternity / At Eternity’s Gate / Old Man in Sorrow” - Vincent van Gogh

V. Diagnosing Mood

Disorders

A. Screening for

Depression

B. Major

Depressive

Episode

C. Approaches To

The Clinical

Interview

D. Depressive

Spectrum

LINK: Vincent van Gogh (Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vincent_van_Gogh)

Screening for Depression

The primary care physician’s most powerful screening tool for depression is patient observation and active listening skills. Most

depressed patients do not realize they are depressed – and this is especially true in elderly patients. A physician should consider that a

patient may have depression in the setting of unexplained physical symptoms or complaints. The higher the number of somatic

complaints that a patient has, the higher the risk that they may have a mood disorder. Other clues may be a patient with persistent

worries or concerns about medical illness, complaints that do not respond to typical interventions, or complaints outright of anxiety or

panic attacks. Patients with substance abuse issues may also suffer from a mood disorder. A careful history of present illness, past

medical history, social and family history, and review of systems may yield more important information for making the diagnosis.

The primary care physician should ask open-ended questions of the patient about normal patterns as well as variations to determine

baseline function and mood. Mood is a range of emotions that a person feels over a period of time, while affect is how a person

Page 6 of 50

E.

F.

G.

H.

I.

J.

K.

L.

M.

N.

Disorders: The

Depressed

Mood

Algorithm

Mood disorder

due to a general

medical

condition

Substanceinduced

depression

Dysthymic

Disorder

Bereavement

Adjustment

disorder with

depressed mood

Seasonal

affective

disorders

Postpartum

depression

Pseudodementia

Manic and

Hypomanic

Symptoms and

Bipolar

Disorders

Suicidal

Patients –

students to

identify

displays his or her mood. The presence of a mood disorder may affect a person’s concentration, attention, motivation, interest, and

sleep, as well as energy level, hunger and satiety levels, sexual pleasure, and pain sensation. These patients also frequently lose

interest and lose pleasure (anhedonia) in things, people, or activities that they used to enjoy. Interruption in personal relationships with

others can be a side effect due to increasing anger and conflicts, lower frustration tolerance, or from apathy and lack of enthusiastic

feelings towards other people. Patients with depression may become emotionally constricted and lose their emotional flexibility.

Depression can impair cognitive function. Cognitive dysfunction is common and patients may state that when they watch television

they lose the point of the story; they read the same page of a book over and over again without comprehension; or lose the point of

conversations with other people. A depressed patient’s memories may amount to more of selective recall, and normal perceptions may

become distorted. Severe cognitive impairment due to depression is known as pseudodementia, and may be seen in elder populations

or patients with central nervous disorders.

Psychomotor activity is usually decreased in depressed patients. Psychomotor retardation is present when thoughts, motor movements,

or speech are slowed down. Psychomotor agitation can also occur and is present when patients experience unintentional and

purposeless movements – such as unstoppable crying, pacing around a room, or hand-wringing. Frequently patients may complain of

insomnia. In addition to having difficulty falling asleep, depressed patients typically wake up in the middle of the night or early in the

morning with feelings of sadness, anxiety, or thoughts of dread or doom. They may also sleep excessively or stay most of the day in

bed.

Depressed patients may also have self-worth that goes through turbulent fluctuations. For depressed patients, past events may be

viewed with extreme guilt and self criticism, and feelings of worthlessness. Patients may view themselves and their world as hopeless.

Suicidal ideation or a history of suicidal attempts from the patient should be assessed. Asking depressed patients about recent

bereavement is also important to note.

A past medical history of prior episodes of depression is a very important question because you may be observing a relapsing episode.

In addition, the physician should inquire about a previous history of bipolar disorder because inappropriate treatment with an

antidepressant-therapy alone in these patients may precipitate a manic episode. It is also important to inquire about a family history of

depression or bipolar disorder.

When to think about screening adults for depression

Personal previous history of depression or bipolar disorder

First-degree biologic relative with history of depression or bipolar disorders

Patients with chronic diseases

Obesity

Chronic pain (e.g., backache, headache)

Impoverished home environment

Page 7 of 50

Financial strain

Experiencing major life changes

Pregnant or postpartum

Socially isolated

Multiple vague and unexplained symptoms (e.g., gastrointestinal, cardiovascular,

neurological)

Fatigue or sleep disturbance

Substance abuse (e.g., alcohol or drugs)

Loss of interest in sexual activity

Elderly age

Adapted from Sharp, LK, Lipsky MS. “Screening for depression across the lifespan: a review of measures for use in primary care

settings.” American Family Physician. 2002; 66: 1001-1008

Question 2) Which are the current recommendations of United States Preventive Screening Task Force for screening adults for

depression in primary care settings?

a)

b)

c)

d)

e)

No recommendation for or against routine screening for depression in primary care settings

Screen only adults with positive risk factors for major depression, such as those with a positive family history or chronic pain

Screen in all primary care practices because it is highly effective

Screen only when the primary care practice has a psychiatrist on staff

Screen only when systems are in place to ensure adequate treatment and follow up

The correct answer is e. The United States Preventive Screening Task Force recommends “screening adults for depression in

clinical practices that have systems in place to assure accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and follow up” (USPSTF, 2006).

The system in place to assure follow up and monitoring can be the primary care physician, their primary care colleagues, or

properly trained staff such as nurses. Access to mental health services, outside the practice, is important should referrals be

necessary for complicated cases (e.g., psychiatrists, therapists, emergency departments, etc.). The USPSTF recommends that

clinicians provide depression screening to eligible patients because of fair evidence that screening improves important health

outcomes and concludes that benefits outweigh harms. The existing literature suggests that screening tests perform reasonably

well in adolescents and that treatments are effective, but the clinical impact of routine depression screening has not been studied

in pediatric populations in primary care settings. (Source: United States Preventive Screening Task Force. Screening for

depression: Recommendations and rationale. November 2006 Recommendations. http://epss.ahrq.gov/PDA/index.jsp)

There are many formal screening tools available such as the Zung Self-Assessment Depression Scale, Beck Depression Inventory,

General Health Questionnaire (GHQ), Center for Epidemiologic Study Depression Scale (CES-D), and the Patient Health

Questionaire-2 (PHQ-2). The USPSTF does not recommend one screening test over another and the interval for screening that is

Page 8 of 50

considered optimal is unknown. Recurrent screening in patients with a history of depression, unexplained somatic symptoms,

substance abuse, chronic pain, or co-morbid psychological conditions may be the most useful. Any screening test that is positive

requires a full diagnostic interview that uses standard diagnostic criteria, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) to determine the presence of major depressive disorder and/or dysthymia.

The Patient Health Questionnaire - 2 (PHQ-2) is a validated primary care tool for depression screening, and is favored because of

the relative ease of using a two question tool and because the USPSTF believes that with current available evidence it is as effective as

longer screening tools.

Patient Health Questionnaire – 2 (PHQ-2)

Screen for depression by asking the following 2 questions:

Over the past 2 weeks, have you been bothered by:

little interest or pleasure in doing things?

feeling down, depressed, or hopeless?

A “no” response to both questions is a negative screen.

A “yes” response to either question OR if the physician is still concerned about depression,

then the physician should ask more thorough assessment questions using

the Patient Health Questionnaire – 9 (PHQ-9).

The Patient Health Questionnaire – 9 (PHQ-9) is a nine item questionnaire that can be completed by the patient before or during a

primary care office visit. It is available in several languages. The PHQ-9 can reliably detect and quantify the severity of depression

using the DSM-IV criteria for major depressive episode. The PHQ – 9 was created by Dr. Robert Spitzer, et al. at Columbia

University and is copyright protected by Pfizer Inc. The PHQ – 9 is also useful for patient follow up visits to assess symptom

management. Instructions on the use of the PHQ – 9 is available on the PDF files below:

LINK: PDF of PHQ – 9 (English)

LINK: PDF of PHQ – 9 (Spanish)

Major Depressive Disorder

Summary of DSM-IV Criteria for Major Depressive Episode

If depressed mood or loss of interest or pleasure persists for more than at least a two-week

period, consider the diagnosis of major depressive episode. The diagnostic criteria are

summarized below:

Page 9 of 50

A. At least five of the following symptoms have been present during the same two-week

period, nearly every day, and represent a change from previous functioning. At least

one of the symptoms must be either (1) depressed mood or (2) loss of interest or

pleasure:

1) Depressed mood (or alternatively can be irritable mood in children and

adolescents)

2) Marked diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities

3) Significant weight loss or weight gain when not dieting

4) Insomnia or hypersomnia

5) Psychomotor retardation or agitation

6) Fatigue or loss of energy

7) Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt

8) Diminished ability to think or concentrate

9) Recurrent thoughts of death, recurrent suicidal ideation without a specific

plan, or a suicide attempt or specific plan for committing suicide

B. Symptoms are not accounted for by a mood disorder due to a general medical

condition, a substance-induced mood disorder, or bereavement (normal reaction to the

death of a loved one).

C. Symptoms are not better accounted for by a psychotic disorder (e.g. schizoaffective

disorder).

A well-known mnemonic that is commonly used to remember the DSM-IV criteria is SIGECAPS:

Sleep

Interest (anhedonia)

Guilt

Energy

Concentration

Appetite

Psychomotor

Suicidality

A major depressive episode can be associated with special features: melancholic, psychotic, or atypical.

Patients with melancholic features will report nearly total anhedonia. Depressed patients with melancholia must have three of the

Page 10 of 50

following symptoms: diurnal variation (depression worse in the morning); pervasive and irremediable depressed mood; marked

psychomotor retardation or agitation; significant weight loss or anorexia; excessive or inappropriate guilt; and early morning

awakening. Depressed patients with melancholic features have the best response to pharmacotherapy.

Depressed patients that have psychotic features such as hallucinations and delusions are at very high risk for suicide even if they deny

suicidal ideation. These patients should be sent for hospitalization immediately and should be under the care of a psychiatrist.

Patients with atypical features have milder depressed symptoms. Depressed patients with atypical features must experience mood

reactivity as well as two of the following: leaden paralysis (enormous effort to walk or exert); hypersomnia; rejection hypersensitivity

(even when the patient is not acutely depressed); overeating or weight gain. These patients respond less to tricyclic antidepressants.

Approaches to Interviewing Patients with Suspected Depression

Depressed patients may feel so helpless, hopeless, indecisive, or lacking in energy that physicians may need to take a more active role

to engage the patient or to show their interest or concern. Again in major depression, the more common complaint is anhedonia and

not depressed mood. Quiet listening and empathy are important approaches physicians can use with patients. A caring and

nonjudgmental tone is critical to allay patient fears of the stigma of depression. Introducing the topic of depression with an

educational statement first and then asking the patient for their response may help the patient not feel judged (example – “Patients

who have had a heart attack sometimes get depressed or down after the event. Has this been happening to you recently?”). Making a

statement instead of a question may allow the patient to have permission to be depressed and to know that you are willing and open to

discussing the issue without judgment (example – “It sounds like you have been pretty down recently.”).

Physicians may want to excuse depression symptoms in patients by attributing them to stressors or complications of life. Patients with

increasing financial stress, work difficulties, and relationship problems should raise further possibility of major depression.

These patients may be unduly critical of themselves but may also be critical of others including their doctors. It is important to

recognize when they evoke frustration or anger in you so that you can avoid negative countertransference and avoid directing anger

back at the patient.

Depressive Spectrum Disorders: The Depressed Mood Algorithm

Major depressive episode is just one of several depressive spectrum disorders. In addition, depression may be associated with chronic

medical illnesses. The following “depressed mood algorithm” can be used in primary care settings to assist in making the differential

diagnosis.

Depressed Mood Algorithm

Page 11 of 50

NO

NO

If NO,

Are the symptoms

due to a stressor?

Is a general medical

condition directly

responsible for the

symptoms?

YES

Mood disorder

due to a general

medical

condition

Is a substance directly

responsible for the

symptoms?

YES

Substanceinduced disorder

Is the depressed mood

or anhedonia present

for at least 2 weeks?

If YES,

Are associated

symptoms present?

YES

Adjustment disorder with depressed

mood

If YES,

Are they best

explained by

bereavement?

NO

Depressive disorder not otherwise

specified or no disorder

If NO,

Has the depressed mood or

anhedonia and milder

associated symptoms been

present for at least 2 years?

NO

Major depressive disorder

YES

Bereavement

YES

Dysthymic disorder

Adapted with permission from “Depression” Janis Cutler MD and Rita Charon, MD. Primary Care Psychiatry and Behavioral

Page 12 of 50

Medicine: Brief Office Treatment and Management Pathways. Edited by RE Feinstein, AA Brewer. Springer Publishing Co., New

York, NY. 1999

Depression Due To General Medical Conditions

Alterations in mood may be related to underlying medical conditions. Depression may be associated with other chronic medical

diseases such as cancer, stroke, heart disease, endocrine disorders, neurological diseases, epilepsy, gastrointestinal diseases,

rheumatologic diseases, and severe anemia. This depression is independent of the psychological impact of the stress of the illness, and

is patho-physiologically related to the underlying condition.

Medical Conditions Associated With Increased Incidence of Depression

Cardiac disease

Ischemic disease, Myocardial infarction

Heart failure

Cancer

Brain cancer

Pancreatic cancer

Endocrine disorders

Hyperthyroidism

Hypothyroidism

Diabetes

Parathyroid dysfunction

Cushing’s disease

Gastrointestinal disorders

Inflammatory bowel disease

Irritable bowel syndrome

Hepatic encephalopathy

Cirrhosis

Neurologic disease

Stroke

Chronic headache

Dementias

Traumatic brain injury

Multiple sclerosis

Parkinson’s disease

Epilepsy

Pulmonary disease

Sleep apnea

Reactive airway disease

Rheumatologic disease

Lupus

Rheumatoid arthritis

Chronic fatigue syndrome

Fibromyalgia

Page 13 of 50

Metabolic disease

Renal failure

Electrolyte disturbances

HIV disease

Syphilis

Hepatitis

Lyme disease

Severe anemia

Infectious disease

Hematologic disorder

Identification of co-morbid disease or conditions is important in patients with depression. Primary care physicians should consider

initial lab testing such as thyroid-stimulating hormone, complete blood count, and chemistry panel. The findings of the complete

history and physical examination may clarify the need for further testing for other diseases or syndromes.

Depression Impacting Existing Medical Illness

Patients who suffer from diabetes, ischemic heart disease, stroke, or lung disorders and who have concurrent depression have poorer

outcomes than those without depression. Depressed patients, in general, have a higher risk of death from heart disease, respiratory

disorders, stroke, accidents, and suicide.

Question 3) Depression may affect the management of general medical illness. Which of the following statement is false?

a)

Patients with depression may exhibit maladaptive interpersonal behaviors which can make collaboration with physicians

more challenging

b) Patients with depression have higher rates of adverse health-risk behaviors when compared to non-depressed patients

c) Patients with aversive symptoms such as pain are at an increased risk for developing depressive disorders

d) The presence of a chronic medical illness is the most prevalent risk factor for the development of depression

e) The importance of screening, diagnosing, and treating depression after a myocardial infarction has been well documented

The correct answer is d. The presence of a chronic medical illness alone is not the most prevalent risk factor for developing

depression. Depressed patients have higher rates of adverse health risk behaviors which may lead to higher risk of death from

heart disease, respiratory disorders, stroke, accidents, and suicide. Chronic pain is known to be a risk factor for developing

depression. Depressed patients may express maladaptive interpersonal behaviors such as anger or non-adherence which may

cause some conflict with their medical providers. Screening, diagnosing, and treating depression after a myocardial infarction has

been found to be of benefit in these patients.

Substance-induced depression

Depression may be induced by substances ingested for recreation or mood alteration or from their withdrawal. These substances

Page 14 of 50

include alcohol, hypnotics, sedatives, opiates, marijuana, amphetamines, cocaine, and other designer drugs (e.g., ketamine, ecstasy).

Prescription drugs used for medical treatment can also cause mood disturbances such as blood pressure medication (e.g., reserpine,

propanolol), anticholinergics, steroids, oral contraceptives, psychotropic medications, and antineoplastic drugs.

Dysthymic disorder

Dysthymic disorder is a chronic form of depression. The signs and symptoms are milder but can cause much distress and dysfunction.

The patient must have at least a two year history of complaints occurring on over half the days to make the diagnosis. It is important

to distinguish dysthymic disorder from major depression because dysthymic disorder is more chronic and unremitting, and less

responsive to pharmacotherapy. Family and friends may experience people with dysthymic disorders to be chronic complainers or

pessimists.

Summary of DSM-IV Criteria for Dysthymic Disorder

A. Depressed mood for most of the day, for more days than not, as indicated either by

subjective account or observation by others, for at least two years. Note: In children and

adolescents, mood can be irritable and duration must be at least one year.

B. Presence, while depressed, of two (or more) of the following:

1) Poor appetite or overeating

2) Insomnia or hypersomnia

3) Low energy or fatigue

4) Low self-esteem

5) Poor concentration or difficulty making decisions

6) Feelings of hopelessness

C. During the two year period (one year for children and adolescents) of the disturbance, the

person has never been without the symptoms in criteria A or B for more than two-months

at a time.

D. No major depressive episode has been present during the first two years of the

disturbance (one year for children and adolescents); i.e, the disturbance is not better

accounted for by chronic major depressive disorder, or major depressive disorder in patial

remission.

E. There has never been a manic episode, a mixed episode, or a hypomanic episode, and

criteria have never been met for cyclothymic disorder.

F. The disturbance does not occur exclusively during the course of a chronic psychotic

disorder, such as schizophrenia, or delusional disorder.

G. The symptoms are not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance (e.g. a drug of

abuse, a medication) or general medical condition (e.g., hypothyroidism).

H. The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational,

Page 15 of 50

or other important areas of functioning.

Bereavement

Bereavement is a normal reaction to the loss of a loved one. It is accompanied by insomnia, sadness, weight loss, decreased appetite.

Symptoms resolve normally within 2 months and do not require psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy. When symptoms persist beyond

2 months, the possibility of a diagnosis of major depression exists. Pathologic symptoms include thoughts of death beyond the wish to

be with the lost loved one, excessive guilt, an overwhelming new sense of worthlessness, severe psychomotor retardation,

hallucinations (other than transiently hearing the voice or seeing the image of the loved one), or the inability to perform usual tasks

and obligations.

Adjustment disorder with depressed mood

Adjustment disorder with depressed mood is diagnosed when the patient has depressive symptoms or complaints within 3 months of

an identifiable psychosocial stressor. Stressors may include academic failure, job loss, or divorce. The stressor causes depressed

symptoms that do not meet the criteria for major depression or dysthymic disorder. The treatment of choice is psychotherapy over

pharmacologic therapy.

Seasonal affective disorders

Major depressive episodes that have a seasonal pattern, particularly with the start of fall or winter, or when natural daylight decreases,

are considered seasonal affective disorders. The diagnosis can not be made if there is a clear psychosocial stressor related to the

change in season. These patients respond to standard antidepressants and psychotherapy, in addition to light therapy.

Depression in pregnancy and postpartum depression

Question 4) You have a 28 year old woman who is in her third trimester of pregnancy. She has been diagnosed with severe

depression and is under the care of a psychiatrist. She wants to discuss with you the risk of taking antidepressants during the rest of

her pregnancy. Which of one of the following statements is true?

a)

If she takes an SSRI (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor), her newborn has a small risk of developing a transient

withdrawal syndrome that may consist of inconsolable crying, irritability, tachypnea, thermal instability, and poor muscle

tone.

b) If she takes an SSRI (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor), her newborn has a small risk of developing a permanent

serotonin syndrome that may consist of inconsolable crying, irritability, tachypnea, thermal instability, and poor muscle tone.

c) If she takes an SSRI, her newborn will likely be larger than a newborn delivered by a mother not taking antidepressants.

Page 16 of 50

d) Tricyclic antidepressants have teratogenic effects.

e) She should stop any antidepressant a few weeks prior to her due date to prevent neonatal withdrawal syndrome.

The correct answer is a. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are the agents of choice. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

and tricyclic antidepressants appear to have no teratogenic effects. There is also a small but significant risk of “withdrawal

syndrome” in the newborn if serotonergic antidepressants are taken during the third trimester. This “withdrawal syndrome”

consists of irritability, inconsolable crying, tachypnea, thermal instability, and poor muscle tone but is usually mild and transient.

More recently, a case-control study reported a possible association between SSRI use in late pregnancy and persistent pulmonary

hypertension in the offspring.

Although depression in pregnancy and postpartum depression is beyond the scope of this web module, it is important for primary care

physicians to be aware of screening these patients for timely intervention.

Medical management of depressed patients during pregnancy usually stirs discomfort in physicians because of fear of teratogenic

effects in the fetus. Adverse effects of not treating this population are well documented, as well as the safety profiles of commonly

prescribed psychiatric medications. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are the agents of choice. Fluoxetine and tricyclic

antidepressants appear to have no teratogenic effects, and new data shows similar safety profiles for other selective serotonin reuptake

inhibitors. The mood stabilizers (e.g., dilantin, valproic acid, carbamazepine) appear to be teratogenic. The decisions regarding the use

of psychiatric medications should be individualized. The most important factor is usually the patient’s level of functioning in the past

when she was not taking medications. There is a small but significant risk of “withdrawal syndrome” in the newborn if serotonergic

antidepressants are taken during the third trimester. This “withdrawal syndrome” consists of irritability, inconsolable crying,

tachypnea, thermal instability, and poor muscle tone but is usually mild and transient. Overall, pregnant patients, once identified with

depression, should be under the care of a psychiatrist and an obstetrician or family physician with experience in high risk obstetrics.

Psychotherapy has also been found to be useful in these women.

Postpartum depression typically occurs within one month of delivering a baby. Normal “baby blues” can begin 24 hours after delivery

and last up to 10 days. Postpartum depression is not different from a major depressive episode, but the primary care physician or

obstetrician should recognize the symptoms as immediate interventions can have positive outcomes for the mother and baby. One

important challenge is that the onset of postpartum depression frequently occurs before the patient is seen for a routine six-week

postpartum visit. The risk-benefit decision about whether to start antidepressants in a breastfeeding woman is based on the severity of

the depression and the need for pharmacotherapy, rather than any known risks to the infant.

More information on treatment of depression in pregnancy, postpartum women, and breastfeeding woman can be found in this web

module’s library.

LINK: Ward, R. Zamorski, M. “Benefits and Risks of Psychiatric Medications in Pregnancy” Am Fam Physician. 2002;66:62936,639.

Page 17 of 50

LINK TO RESOURCE FOR PATIENTS AND DOCTORS ON PREGNANCY AND DEPRESSION: www.womensmentalhealth.org

Depression in the Elderly and Pseudodementia

QUESTION 5) Which one of the following statements is true about depression in the elderly?

a) Physicians are more likely to diagnose depression correctly in the elderly than in younger people.

b) Depression in the elderly is less important than in younger patients because depression is a normal part of the aging process.

c) Patients who are elderly when their first depressive episode occurs have a relatively high likelihood of developing recurring

chronic depression.

d) Risk factors for depression in elderly persons include a history of depression, chronic medical illness, male sex, being single

or divorced, brain disease, alcohol abuse, use of certain medications, and stressful life events.

e) The long term prognosis for the elderly suffering from depression is poor even with treatment.

The correct answer is c. As in younger populations, depression in the elderly is often not diagnosed and not treated by

physicians. A popular misconception by patients, families, and physicians is that depression is a normal part of the aging process.

Risk factors for depression in elderly persons include a history of depression, chronic medical illness, female sex, being single or

divorced, brain disease, alcohol abuse, use of certain medications, and stressful life events. Patients who are elderly when their

first depressive episode occurs have a relatively high likelihood of developing recurring chronic depression. With proper

diagnosis and management, depression in the elderly is treatable and has a good prognosis. (Source: Birrer, RB, Vemuri SP.

Depression in later life: A diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Am Fam Physician 2004; 69 (10): 2375-2382)

Depression in the elderly is not part of the normal aging process. This common misconception may lead elderly patients, or their

families, not to seek appropriate help. It can also lead physicians to miss the diagnosis of depression in the elderly and leave it

untreated. A common complaint in elderly patients is not depression but insomnia, anorexia, and fatigue. Treatment with

antidepressants, especially selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors can be useful. Patients who are elderly when they have their first

episode of depression have a relatively higher likelihood of developing chronic and recurring depression. The prognosis for recovery

is equal in young and old patients, although remission may take longer to achieve in older patients.

Pseudodementia, associated with severe depression, can be easily mistaken for dementia, especially in the elderly or persons with

underlying neurological disease (e.g., strokes, etc). The symptoms of pseudodementia include marked psychological distress, inability

to concentrate or complete daily tasks, and marked cognitive dysfunction. Differentiating between dementia and pseudodementia is

important. Typically, patients suffering from pseudodementia will exhibit profound concern about their impaired cognitive function,

in contrast with patients with a diagnosis of dementia, who may tend to minimize their disability. In addition to pharmacotherapy,

electroconvulsive therapy may be warranted in patients with pseudodementia.

Page 18 of 50

All patients with depression of all ages, including the elderly, should have a mini-mental status examination at baseline. Patients

successfully treated of their major depression will see their pseudodementia and cognitive dysfunction improve.

Reproduced with permission from Birrer, R., Vemuri, S. “Depression in Later Life: A Diagnostic and Therapeutic Challenge.”

American Family Physician. 2004;69:2375-82.

More information on depression in the elderly is available in this web module’s library.

LINK TO: Birrer, RB, Vemuri SP. Depression in later life: A diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Am Fam Physician 2004; 69 (10):

2375-2382

Manic and Hypomanic Symptoms: Bipolar Disorder

Page 19 of 50

Question 6) You are evaluating a 35 year old male in your primary care practice. He has a history of depression and occasional panic

attacks. His previous physicians treated his panic symptoms with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) approved for panic

disorders but the medications made him more restless, agitated, and unable to sleep. Upon further questioning, you discover he has

been having symptoms with impairing depressive episodes and anxiety since late childhood. His father was hospitalized with a manic

episode on one occasion. Upon further exploration, which one of the following would be most specific for confirming the diagnosis of

bipolar disorder?

a)

b)

c)

d)

e)

His brother has a confirmed diagnosis of bipolar I disorder

His sister has a confirmed diagnosis of bipolar II disorder

The patient has symptomatic improvement on lithium

His mother’s mania improved with lithium

The patient has had a hypomanic episode

The correct answer is e. The risk of having bipolar disorder is higher in persons with first degree relatives with bipolar disorder.

Incidental improvement of symptoms with lithium may also provide clues. Of all these findings, the most specific to the diagnosis

is the patient having a hypomanic episode himself. (Source: American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

of Mental Disorders, ed 4 text revision, American Association, 2000. Washington DC)

A major depressive episode can appear as a unipolar disorder, but all primary care physicians should be aware that this presentation

may be part of an underlying bipolar disorder. Primary care physicians who diagnose and treat patients with depression should

carefully assess patients for a history or current complaint of manic and hypomanic symptoms. Misdiagnosis of a bipolar disorder

patient presenting with major depressive symptoms can lead to mistreatment with antidepressants alone, which may precipitate a

manic episode. A manic mood is characterized by irritability or abnormal euphoria. Hypomania can be seen as a lesser degree of

mania that lasts for a shorter duration. Hypomanic patients usually can continue with their normal life routines and don’t require

hospitalization. A patient with a “mixed state” has to technically satisfy all the criteria of a major depressive disorder and mania at the

same time. DSM-IV criteria for mania and hypomania can be found on the next table. Patients with bipolar disorder should be referred

for collaborative care with a psychiatrist.

Summary of DSM-IV Criteria for Manic Episode

A. A distinct period of abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable

mood, lasting 1 week (or any duration if hospitalization is necessary).

B. During the period of the mood disturbance, three (or more) of the following

symptoms have persisted (four if the mood is only irritable) and have been present

to a significant degree:

1) Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity

2) Decreased need for sleep (e.g., feels rested after only 3 hours of sleep)

3) More talkative than usual or pressure to keep talking

Page 20 of 50

4) Flight of ideas or subjective experience that thoughts are racing

5) Distractibility (i.e., attention too easily drawn to unimportant or irrelevant

external stimuli)

6) Increase in goal-directed activity (either socially, at work or school, or

sexually) or psychomotor agitation

7) Excessive involvement in pleasurable activities that have a high potential

for painful consequences (e.g., engaging in unrestrained buying sprees,

sexual indiscretions, or foolish business investments)

C. The symptoms do not meet the criteria for a Mixed Episode.

D. The mood disturbance is sufficiently severe to cause marked impairment in

occupational functioning or in usual social activities or relationships with others, or

to necessitate hospitalization to prevent harm to self or others, or there are psychotic

features.

E. The symptoms are not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance (e.g., a

drug of abuse, a medication, or other treatment) or a general medical condition (e.g.

hyperthyroidism).

Note: Manic-like episodes that are clearly caused by somatic antidepressant treatment

(e.g. medication, electroconvulsive therapy, light therapy) should not count toward the

diagnosis of Bipolar I Disorder.

Summary of DSM-IV Criteria for Hypomanic Episode

A. A distinct period of persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood, lasting

throughout at least 4 days, that is clearly different from the usual non-depressed mood.

B. During the period of mood disturbance, three (or more) of the following symptoms have

persisted (four if the mood is only irritable) and have been present to a significant

degree:

1) Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity

2) Decreased need for sleep (e.g., feels rested after only 3 hours of sleep)

3) More talkative than usual or pressure to keep talking

4) Flight of ideas or subjective experience that thoughts are racing

5) Distractibility (i.e., attention too easily drawn to unimportant or irrelevant

external stimuli)

6) Increase in goal-directed activity (either socially, at work or school, or

sexually) or psychomotor agitation

7) Excessive involvement in pleasurable activities that have a high potential

for painful consequences (e.g., engaging in unrestrained buying sprees,

sexual indiscretions, or foolish business investments)

C. The episode is associated with an unequivocal change in functioning that is

Page 21 of 50

uncharacteristic of the person when not symptomatic.

D. The disturbance in mood and the change in functioning are observable by others.

E. The episode is not severe enough to cause marked impairment in social or occupational

functioning, or to necessitate hospitalization, and there are no psychotic features.

F. The symptoms are not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance (e.g., a

drug of abuse, a medication, or other treatment) or a general medical condition (e.g.

hyperthyroidism).

Note: Manic-like episodes that are clearly caused by somatic antidepressant treatment (e.g.

medication, electroconvulsive therapy, light therapy) should not count toward the diagnosis

of Bipolar II Disorder.

Assessing The Risk of Suicide

“The Scream” – Edvard Munch

LINK: Edvard Munch (Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edvard_Munch)

Page 22 of 50

Patients with depression may be at increased risk for suicide (Kahn, 1999. NYCDOH, 2006, Mann, 2005). Any patient that has a

positive screening for depression should be evaluated for suicide risk. Asking about suicidal thoughts can save the patient’s life.

Contrary to many physicians’ fear, asking about suicidal plans or ideation does not make patients more prone to commit suicide.

Patients are usually relieved that they have been asked about their feelings and thoughts. Asking about suicidal ideation or plans

conveys your interest in their well-being.

Questions in Assessing Suicidal Risk

Current thoughts of harming or killing self

Current plans to harming or killing self

Prior suicide attempts (critical indicator of future suicide risk)

Family history of mood disorder, alcoholism, or suicide

Actions or threats of violence to others

Access to firearms

Male

Elderly

Significant comorbid anxiety or psychotic symptoms and active substance abuse

Poor social support system or living alone

Recent loss or separation

Hopelessness

Preparatory acts (e.g., putting affairs in order, suicide notes, giving away personal

belongings)

Physicians can initiate the topic of suicidal ideation with questions about the patient’s feelings about life.

“Did you ever wish you could go to sleep and never wake up?”

“Have you ever felt life was not worth living?”

Depending on the response, more specific questions about suicidal ideation can be asked.

“Do you ever feel others would be better off without you?”

“Are you having thoughts about killing yourself?”

“Have you thought about killing or hurting others?”

If suicidal ideation is elicited, physicians should ask patients if they have a suicidal plan (e.g., how, when, where). A patient that is

actively thinking about suicide and has a plan for suicide constitutes a medical emergency. This is especially true in patients with

previous suicide attempts. 911 should be called for safe transport to the nearest emergency room for psychiatric care. Prediction of

which patients with suicidal ideation will attempt or commit suicide is very poor.

Page 23 of 50

The Institute of Mental Health has made recommendations for physicians who are assisting potentially suicidal patients. It is

important to monitor your own reactions to a suicidal patient. Stay calm and don’t appear threatened so that the patient feels secure

and maintains the doctor-patient dialogue. Listen attentively so that the patient feels validated about their distress and is not ignored.

Avoid judgmental statements. Emphasize that suicidal feelings worsen with stress, but is a treatable condition. Also highlight that

suicide causes family members and friends great pain that lasts for years. Make it clear to the patient that he or she will have input into

their treatment along with you and the psychiatric team as part of a partnership.

Question 7) Outpatients at risk for suicide should not receive large supplies of antidepressants in case of overdose. Which one of the

following statements is true about antidepressants and suicide?

a) Fluoxetine has been shown to lead to more suicide attempts in adolescents than use of placebo.

b) Norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (NRIs) are less like than selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to be associated

with suicidal thoughts in adolescents.

c) Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are more lethal in overdose than SSRIs.

d) Suicide rates are higher with TCAs than with SSRIs.

The correct answer is c. Tricyclic antidepressants are more lethal in overdose over selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. The

risk of suicide in all patients who are recovering from major depression may transiently increase during initial treatment, but

whether antidepressants possibly cause increased suicide risk is extremely controversial. Increased energy to act on suicidal

ideation is only one of the possible explanations currently under consideration. Monitoring patients closely during treatment is

paramount and is part of “psychiatric treatment”. Fluoxetine is the only antidepressant found to be effective in children and

adolescents, but close surveillance for suicidal ideation or plans is again warranted. The average risk of suicide in general was 4%

with antidepressants and 2% on placebo. (Sources: Jick SS, Dean AD, Jick H. Antidepressants and suicide. BMJ 1995; 310

(6974): 215-218; Simon GE. How can we know whether antidepressants increase suicide risk? Am J Psychiatry 163:1861-1863,

2006.)

A link to a recent article on whether antidepressants increase suicide risk and the advent of “black box” warnings is available in

the library.

VI. Treatment

Recommendations for

Major Depressive

Disorder

LINK: Simon GE: How can we know whether antidepressants increase suicide risk? Am J Psychiatry 163:1861-1863, 2006.

Treatment Recommendations for Major Depressive Disorder

Successful treatment of major depressive disorder starts with a thorough assessment of the patient. As discussed previously and based

on recommendations of the American Psychiatric Association, healing begins with “psychiatric management” of the patient, followed

by three phases of treatment. This may be done by the primary care physician, and / or psychotherapist, and / or psychiatrist

depending on the history, complexity, and degree of severity of the depression. The following recommendations are for Major

Page 24 of 50

Depressive Disorder, and although no existing scientific literature has been established – it may apply to other syndromes such as

dysthymic disorder.

Psychiatric Management

1.

Perform a diagnostic evaluation to determine if the diagnosis of depression is warranted or if other psychiatric or medical

conditions exist.

History of present illness and current symptoms

Psychiatric history (e.g., symptoms of mania, previous history of psychiatric treatment, response to previous

psychiatric treatments)

General medical history

History of substance abuse disorders

Personal history (e.g. psychological development, response to major life events and transitions)

Social history

Occupational history

Family history

Medication review

A review of systems

A physical examination

A mental status examination

Diagnostic studies as indicated (e.g., TSH, CBC, Basic Chemistry Profile)

2.

Evaluate for the safety of the patient and of others. This evaluation is crucial.

Presence of suicidal or homicidal ideation or plans

Access to a means for suicide and the lethality of the means (e.g. access to handguns)

Presence of psychotic symptoms (e.g. command hallucinations or delusions)

Severe anxiety

Concurrent alcohol or substance use

History of previous attempts

Family history of suicide

Recent exposure to another person who committed suicide

3.

Evaluate functional impairment by assessing:

Interpersonal relationships

Work

Page 25 of 50

Living conditions

Health and medical related needs

4.

Determine a treatment setting. This can vary from ambulatory settings with a primary care provider only, ambulatory settings

with a primary care provider in conjunction with a psychiatrist, day programs, to involuntary psychiatric hospitalization.

Criteria for involuntary hospitalization are usually set by local jurisdictions. Patients should be treated in the setting that is

the safest and is the most effective. The setting should be reassessed at follow up visits. The following situations require

referral to psychiatrist:

Suicide risk

Bipolar disorder or manic episode

Psychotic symptoms

Severe decrease in level of functioning (e.g., unable to care for self)

Recurrent depression

Chronic depression

Depression that is refractory to treatment

Cardiac disease that requires tricyclic antidepressants treatment (contraindication)

Need for electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)

Lack of available support system

Any diagnostic or treatment questions

5.

Establish and maintain a therapeutic alliance. Major depression is a chronic disease and it requires that the patient actively

engages and adheres to long periods of treatment. Symptoms of major depressive disorder (e.g., poor motivation, cognitive

dysfunction, pessimism, etc.), side effects of medications, and misunderstandings between the physician and patient can be

major obstacles to adherence.

Pay attention to concerns patients and their families.

The physician should be aware of any transference or countertransference issues with the patient (e.g., frustration or

anger from or toward the patient, etc.).

6.

Continue to monitor the patient’s psychiatric status and safety. With treatment, some symptoms may improve while others

emerge.

Significant changes in psychiatric status or emergence of new symptoms requires diagnostic and management

reassessment.

7.

Provide patient education and, if appropriate, to the patient’s family. Effective education will allow patients to make

informed decisions about their treatment and improve adherence.

Emphasize that major depression is a “real” illness and not a moral defect.

Page 26 of 50

Effective treatment is available and necessary.

Discuss anticipated side effects of treatments.

Education of family and friends is important

Support groups are available for patients and their families

8.

Enhance treatment adherence.

It is critical for the physician to monitor the patient closely especially as they begin to feel better as the patient may

start to focus on the side effects of treatment rather than the benefits.

The patient should be encouraged to verbalize any concerns or issues.

Review with the patient when and how often to take their medication.

Explain that beneficial effects may take 2 – 4 weeks to be noticed.

Explain the need to continue taking the medication even after the patient feels better.

Remind the patient the need to consult with a physician before stopping medication.

Explain to the patient how to access you, a colleague, or the health care team in case a question or problem arises.

Consider issues of polypharmacy especially in elderly patients.

Consider the financial impact of medications on patients.

Encourage the family to help in the process of adherence.

9.

Work with the patient to address early signs of relapse.

Exacerbations and relapse are common in major depressive disorder, and patients and families should be educated

on this point.

A review of signs and symptoms of relapse with the patient is critical as the next episode may contain different

depressive characteristics.

Emphasize the need to seek early treatment and intervention if symptoms arise to prevent a full-blown exacerbation.

The three phases of treatment of major depression

Treatment consists of three phases:

1.

2.

3.

Acute Phase – Remission is induced (minimum 6 – 8 weeks in duration).

Continuation Phase – Remission is preserved and relapse prevented (usually 16 – 20 weeks in duration).

Maintenance Phase – Susceptible patients are protected against recurrence or relapse of subsequent major depressive

episodes (duration varies with frequency and severity of previous episodes).

Remission and relapse have been defined by the American Psychiatric Association. Remission is the return to the patient’s baseline

level of symptom severity and functioning. Remission should not be confused with significant but incomplete improvement. Relapse

Page 27 of 50

is the re-emergence of significant depressive symptoms or dysfunction after remission has been achieved.

Acute phase treatment

The goal of acute phase treatment is to induce remission and typically lasts a minimum 6 – 8 weeks in duration.

For patients with mild to moderate depression, the initial treatment modalities may include pharmacotherapy alone, psychotherapy

alone, or the combination of medical management and psychotherapy. As stated prior, psychiatric management must be integrated

into treatment regardless of the initial approach.

Antidepressant medications

Antidepressant medications can be used as initial treatment modality by patients with mild or moderate depression. Clinical features

that may suggest that antidepressant medication is preferred over other modalities are a positive response to prior antidepressant

treatment, significant sleep and appetite disturbance, severity of symptoms, or anticipation by the physician that maintenance therapy

will be needed. Patient preference for antidepressant medication alone should be taken into consideration. Most primary care

physicians can medically manage these patients in their practices as long as they continue to monitor the patient’s symptoms closely.

The frequency of monitoring in the acute phase of pharmacotherapy is from once a week to multiple times a week.

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy alone may be considered as initial treatment modality for patients with mild to moderate depressive disorder. Clinical

features that suggests the use of psychotherapy over other modalities are the presence of psychosocial stressors, interpersonal

difficulties, intrapsychic conflict, and any axis II comorbidities (personality disorders as per DSM-IV). In addition, patient preference

for psychotherapy alone should be taken into consideration, as well as a woman’s desire to get pregnant, be pregnant, or to breastfeed.

Most primary care physicians will refer these patients to a professional psychotherapist for management. The frequency of monitoring

in the acute phase of psychotherapy is from once a week to multiple times a week.

Combination antidepressant medication and psychotherapy

The combination of antidepressant medication and psychotherapy may be the initial treatment approach for patients with moderate

depression in the presence of psychosocial stressors, interpersonal difficulties, intrapsychic conflict, and any axis II comorbidities.

Combination therapy may also be appropriate for patients with only partial remission on one type of treatment, or with a history of

poor adherence to treatment. Most primary care physicians can medically manage these patients while referring them to a professional

psychotherapist for co-management.

Initial acute phase treatment approaches for patients with severe depressive symptoms

Page 28 of 50

Antidepressant medications alone can be used as initial treatment modality by patients with severe depression. There is insufficient

evidence that psychotherapy alone is effective for patients with severe depression. The combination of antidepressant medication and

psychotherapy may be the initial treatment approach for patients for patients with severe depression in the presence of psychosocial

stressors, interpersonal difficulties, intrapsychic conflict, and any axis II comorbidities. Patients with depression and psychotic

symptoms, catatonia, or severe impairment may be considered for combination therapy with antidepressants, antipsychotics, and / or

electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Patient with severe depression are usually referred for care under a psychiatrist.

Assessing an adequate response in the acute phase with mild to moderate depression

Although the goal of acute phase treatment is to return patients to their functional and symptomatic baseline, it is common for patients

to have a substantial but incomplete response to acute phase treatment. Structured tools that measure depression severity and

functional status may be used for follow up assessment (e.g., PHQ- 9, Beck Depression Inventory, etc.). It is important to not

conclude treatment for these patients at this phase as it may be associated with poor functional outcomes. The degree of an “adequate

response” to treatment of depression has been loosely defined: non-response is the decrease in baseline symptoms of 25% or less;

partial response is a 26 – 49% decrease in baseline symptoms; partial remission is 50% or greater decrease in baseline symptoms with

residual symptoms; and remission is the complete absence of symptoms). When patients have not fully responded at this phase, the

most important first step is increasing the dose.

Overall, if after the initial 4 – 8 weeks there is not a moderate improvement in baseline symptoms in the acute phase, then a

reassessment of the diagnosis, medication regimen and / or psychotherapy, adherence, substance or alcohol use is in order. Increasing

the treatment dose is the first step to be considered. If 4 – 8 weeks after the increase of treatment dose there is not a moderate

improvement in symptoms, another review should occur. Other treatment options should then be considered in consultation with a

psychiatric specialist.

Question 8) From our initial opening clinical case, Mr. George is a 44 year old male who you found to have major depression.

Administration of a standard depression questionnaire (such as the PHQ – 9) found his depression to be of moderate severity. You

started him on antidepressants. You see him 8 weeks later after starting the antidepressant medication and his appetite is back, he is

sleeping well, and concentrating better at home and at work. He still feels tired but denies feeling depressed. He still has not assumed

his normal social activities. You re-administer the same standard depression questionnaire, and conclude that he has achieved partial

remission. Reassessment has found no issues with substance abuse or adherence issues with his medications. After this initial

reassessment, which one of the following is the most appropriate first step in treatment options?

a)

b)

c)

d)

Maintain the current dosage of medication and see him back in 4 to 8 weeks.

Increase the dose of the medication and see him back in 4 to 8 weeks.

Change the medication.

Recommend adjunct psychotherapy.

Page 29 of 50

e)

Consult with a psychiatrist.

The correct answer is b. In the acute phase of treatment, if after 4 – 8 weeks there is not a moderate improvement in baseline

symptoms in the acute phase, then a reassessment of the diagnosis, medication regimen and / or psychotherapy, adherence,

substance or alcohol use is in order. The first step is increasing the dose of the medication since he achieved only partial

remission at the initial dose. If after another 4 – 8 weeks, Mr. George is not improved, consideration can be given to again

increasing the dose of the medication, changing to a different medication, or begin adjunct psychotherapy. If 4 – 8 weeks after the

change in treatment there is not a moderate improvement in symptoms, another review should occur. Other treatment options

should then be considered in consultation with a psychiatric specialist – or at any time the primary care physician feels

improvement is not optimal. (Source: Working Group on Major Depressive Disorders. Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of

Patients With Major Depressive Disorder. American Psychiatric Association. 2000. Washington D.C.)

Continuation Phase Treatment

Patients who have been treated with antidepressant medications in the acute phase should be maintained with this regimen to prevent

relapse. This “continuation phase” should last for 16 – 20 weeks after remission. “Psychiatric management” should continue in this

phase. The American Psychiatric Association recommends the medication doses used in the acute phase be maintained in the

continuation phase. There is increasing data to support the continued use of specific effective psychotherapy in this phase. The use of

ECT in this phase has not been well researched. The frequency of visits in the continuation phase may vary. Stable patients may be

seen once every 2 – 3 months. Patients in active psychotherapy may be seen several times a week.

Patients who remain stable throughout the continuation phase, and who are not candidates for the maintenance phase (e.g., recurrent

relapsing chronic depression, etc.), can be considered candidates for discontinuation of treatment.

QUESTION 9) A 35 year old female returns for a follow visit after you have successfully treated her first episode of uncomplicated

major depression. After 6 weeks of treatment with an antidepressant, all of her depressive symptoms have resolved. Based on the

evidence, the total length of treatment with antidepressants should be at a minimum:

a)

b)

c)

d)

e)

3 months

6 months

9 months

12 months

Indefinite

The correct answer is b. Based on the treatment recommendations of the American Psychiatric Association, this uncomplicated

patient with her first major depressive episode would have had an initial six weeks of antidepressant treatment. This six week

period in the acute phase of treatment has apparently induced complete remission of symptoms. The evidence would recommend

Page 30 of 50

another 16 – 20 weeks of continuation phase treatment. The minimum total length of acute and continuation phase treatment for

this patient would be about 6 months. (Source: Working Group on Major Depressive Disorders. Practice Guidelines for the

Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder. American Psychiatric Association. 2000. Washington D.C.)

Maintenance Phase Treatment

Between 50 – 85% of patients with a single major depressive episode will have another episode. Maintenance phase treatment is

designed to prevent recurrence. Issues to consider in using maintenance phase treatment are severity of episodes (e.g., suicidal

ideation or attempts, psychotic symptoms, functional impairment); risk of recurrence (e.g., residual symptoms between episodes,

number of recurrent episodes); comorbid conditions; side effects experienced with continuous treatment; or patient preference.

The same treatment that was effective in the acute and continuation phase should be continued in the maintenance phase. The doses of

medication in the previous phases are usually maintained. The type of psychotherapy employed dictates the frequency of visits in the

maintenance phase (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy decrease to once a month, while psychodynamic

psychotherapy maintains the same previous frequency). Combination therapy (psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy) may be

beneficial for some patients although it is not well studied. Patients with recurrent moderate or severe depressive episodes who don’t

respond well to pharmacotherapy may be candidates for periodic ECT. Frequency of visits in the maintenance phase can vary as in the

continuation phase.

The length of maintenance treatment that is optimal is unknown. Factors that may influence this period may be frequency and severity

of recurrent episodes, persistence of symptoms after a period of recovery, tolerability of treatment, and patient preference. Some

patients may require indefinite maintenance treatment.

Question 10) For which one of the following patients is a trial of discontinuation of antidepressant medication appropriate?

a)

A 30 year old male with is his first lifetime episode of major depression who is now asymptomatic after taking his

medication for 3 months.