Changing Landforms Packet - Mercer Island School District

advertisement

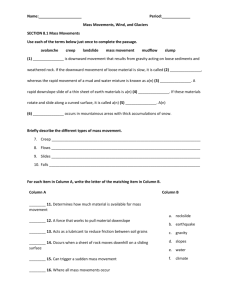

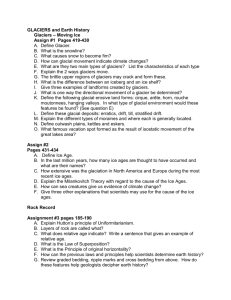

CHANGING LANDFORM SLandform: A feature of the Earth’s surface, such as a mountain, valley, hill, lake or river. When we look toward the mountains of the Pacific Northwest, it seems as if they have always been there, and will never change. From one day to the next, or even one year to the next, they look the same. Yet, before our very eyes, they are changing. Some are being eroded away and others are being built up. It happens so slowly, we don’t see it. If we were to go into the mountains, however, we could see changes taking place. Looking in a stream, we would see bits of sand or gravel, maybe even large boulders, being moved along by the water. This debris is being washed down from the mountains and will settle somewhere in the lands below. Wind blowing over rocky summits scours the cliffs, gradually wearing them down. If we watch closely, we might be able to see bits of sand blowing against the rock. In the crater of Mt. St. Helens, volcanic activity is slowly forming a lava dome, which is gradually rebuilding the shattered peak. From a distance, we cannot see these changes occurring, but they are. Watching the constant change of landforms is a bit like watching a clock. Small amounts of change are easy to see, such as the rolling pebbles in a stream and the motion of a second hand. Larger changes are less visible over a short period of time, like the filling of a lake with silt, and the motion of an hour hand. If we return to a clock an hour after we first look at it, we can see that the hour hand has moved. If we could come back to a lake 10,000 years after we first looked at it, we would see it has changed also. Sometimes spectacular changes take place: landslides, floods, or volcanic eruptions, for example. Mt. Saint Helens became some 2000 feet shorter in a matter of seconds on May 18, 1980. © 1993 by BCS Educational Aids, Inc. LANDFORMS2 1 1. Explain why it seems to us that most landforms never change. __________________ _______________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________ 2. Give at least one example of tiny changes that are always taking place in the land. _______________________________________________________________________ 3. Sometimes a big change suddenly occurs. Give an example of such a change. _______________________________________________________________________ 4. Below are some things that can cause landforms to change. Think of one way in which each may cause a change. A. Rain Falling. ______________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________ B. Wind. ___________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________ C. Rivers and streams. _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________ D. Waves crashing on rocks at the ocean. __________________________________ _________________________________________________________________ E. Freezing temperatures. _____________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________ © 1993 by BCS Educational Aids, Inc. LANDFORMS2 2 VOLCANIC LANDFORM S In the Northwest, some of the most visible landforms are those created by volcanoes. A volcano is an opening in the Earth’s crust from which lava or other materials is ejected. A mountain formed this way is also called a “volcano.” The most spectacular and visible peaks in the Cascade Range are volcanoes. These include mountains such as Baker, Rainier, St. Helens, Hood, Three Sisters and several more. We are going to look at three kinds of volcanoes: shield volcanoes, cinder cones and stratovolcanoes. Shield Volcanoes A shield volcano spews out very fluid lava. Because it is so runny, the lava coming from the vest flows a long way before it cools and hardens. So, shield volcanoes are usually rather low and wide. Newberry Crater, in Central Oregon, is a shield volcano. Its base is twenty miles across. If a shield volcano is able to keep building for a very long time, it can become huge. The largest mountain in the world is the island of Hawaii. The island is formed by a combination of vie shield volcanoes, rises more than 30,000 feet above the ocean floor, and has a base that is nearly 1000 miles in diameter. Sometimes shield erupt from a series of long cracks or “fissures” in the Earth’s crust, rather than from a single vent. When this happens, the volcano may not build up any peak at all. Instead, the lava pours out rapidly across the land, covering thousands of square miles before it cools and hardens. The Columbia Plateau is formed by these types of fissure flows. Massive eruptions covered much of Eastern Washington, Eastern Oregon and Southern Idaho with a type of lava called “basalt.” Basalt is very hot when it leaves the vents and is very fluid. It is very dark brown in color when it cools and often man tiny gas bubbles are trapped within the hardened lava. The thicker flows cooled very slowly and formed tall columns, which can be seen in the sides of cliffs. In some places, basalt layers are thousands of feet deep. A shield volcano is usually low in elevation and has a very wide base. © 1993 by BCS Educational Aids, Inc. LANDFORMS2 Basalt often forms columns while cooling 3 Cinder Cones Cinder cones are rather small volcanic peaks, usually growing to no more than a thousand feet in height. They are built of pyroclastic debris such as ash, cinders, and chunks of broken lava. Cinder cones are usually fairly smooth, and from a distance, look much like the pile of sand you would get if you poured in onto a table through a funnel. Since no fluid lava pours out of a cinder cone, the loose debris tumbles down the sides and is not well protected from erosion. Many cinder cones can be found in high desert of Central Oregon. Stratovolcanoes Tallest, most prominent peaks in the Cascade Range are “stratovolcanoes.” Stratovolcanoes tend to stand from other peaks in the range. They sit like giant pyramids above the jumbled ridges and lower mountains. Most are capped with a mantle of snow and ice that lasts throughout the year. Two of the most prominent are Mt. Rainer (14,410 feet tall), and Mt. Hood (11,225 feet tall). Stratovolcanoes are essentially built of layers of pyroclastic debris and lava. The pyroclastic debris quickly add height to a mountain during an eruption. Flows of lava help bind the pyroclastic material together and protect it from erosion. Some of the stratovolcanoes of the Cascade Range have been active. The eruption of Mt. Saint Helens in 1980 was a spectacular reminder of the power of these volcanoes. Others have not erupted recently, but still show signs of volcanic life. Stratovolcanoes are tall, massive mountains that can be seen from many miles away. They are some of the most prominent landmarks in the Cascade Range. © 1993 by BCS Educational Aids, Inc. LANDFORMS2 4 Volcanic Areas in the Pacific Northwest Here is a map of the Pacific Northwest. Use the list below the map to label each feature. A. Mt. St. Helens G. Mt. Mazama K. Mt. Rainier B. Mt. Newberry H. Glacier Peak L. Mt. Hood C. Mt. Jefferson I. Diamond Peak M. Mt. Baker D. Mt. McLoughlin J. Three Sisters N. Mt. Adams E. Columbia Plateau Basalt Flows F. Craters of the Moon National Volcanic area © 1993 by BCS Educational Aids, Inc. LANDFORMS2 5 1. Write the name of each type of volcano pictured below. A. __________________________________________ B. ______________________________________ C. _______________________ 2. Which type of volcano helped form the Columbia Basin? 3. Which type formed peaks in Central Oregon? 4. Which type formed Mount Hood? 5. Explain what “pyroclastic debris” is. 6. Which type of volcano is formed mainly of pyroclastic debris? 7. When basalt cools in thick layers, what is formed? 8. Which type of volcano is formed of very fluid lava? 9. Which type of volcano is formed by a mixture of pyroclastic debris and lava? 10. Is there any reason for people to be concerned about volcanic activity in the Northwest? Why or why not? (Please write your answer on the back.) © 1993 by BCS Educational Aids, Inc. LANDFORMS2 6 Now we’ll take a look at a few of the landforms we can find in the Pacific Northwest that are a result of the work of glaciers. Lakes Lakes, both large and small, often have been formed by glacial action. Where ice once covered the land, small lakes, called “kettles” can be found. A kettle formed when a large chunk of ice was left behind by a glacier and was partly covered by glacial debris. As the ice gradually melted, a hole was left in the ground and it filled with water from the melting ice and rain. The result was a small lake. A huge chunk of ice is partly buried. When the ice melts, a lake is left behind. In some places, much larger lakes were created in troughs scooped out by moving ice. These lakes are generally long and fairly narrow. Lake Washington, lake Sammamish, Crescent Lake, Lake Chelan, and Wallowa Lake are some examples of those big glacial lakes. Lake Chelan is one of the most spectacular examples. It reaches from the edge of the Columbia Basin, deep into the Cascade Range, a distance of some 40 miles. The lake is rather narrow, but very deep. The bottom, in places, is 1,000 feet below the surface. Channeled Scablands Across eastern Washington can be found sections of land having no topsoil. Bare rock is exposed in cliffs and sticks out in rough or jagged formations on the surface of the smooth plain. As a whole, these areas are called the ”Channeled Scablands.” They were formed during the Ice Ages by huge flood. Lake Missoula was formed when a part of a glacier moved into the Purcell Trench in northern Idaho and blocked the Clark Fork River near Pend Orielle Lake. The damming of the river caused a huge lake to form, reaching deep into northwestern Montana. Lake Missoula was huge. Its shoreline twisted and turned as the waters filled the valleys of the Northern Rockies. Finally, the pressure of the rising water against the ice became great enough to crack the dam. With a thunderous roar the dam burst, unleashing a violent flood. The lake held more than 50 cubic miles of water, and it took only two weeks to drain away. No river channel could contain the mass of surging water, so it thundered across the plains of the Columbia Basin ripping up top soil, and tearing into the layers of basalt below. © 1993 by BCS Educational Aids, Inc. LANDFORMS2 7 Some of the flood water surged through the Spokane River and rushed into the Columbia. It spilled over the banks of the Columbia and dug new, deep channels Grand Coulee and Moses Coulee. Before long, the water pouring across the basin reached the Columbia River near the TriCities. It swept through Wallula Gap and raced downstream into the Columbia Gorge in the Cascade Mountains. The gorge was not big enough to carry all that water, so it backed up and created a lake that grew to a thousand feet deep in the Pasco Basin. As water surged out of the Columbia Gorge it spilled into the Willamette valley, where it backed up and created a lake that was 400 feet deep. Icebergs drifted quietly across the Willamette Valley after their wild ride from Northern Idaho. Slowly, the flood waters drained away to the sea. This massive flooding must have been spectacular. And it happened not once, but as many as seven different times during the Ice Ages. Moraines We have already seen that moraines are piles of glacial debris left at the snout, or along the sides of glaciers. Sometimes these moraines became dams holding back water collecting in glacial valleys. © 1993 by BCS Educational Aids, Inc. LANDFORMS2 8 One of the most spectacular moraines is at the foot of Wallowa Lake in the remote northeastern corner of Oregon. During the Ice Ages a system of glaciers formed in the Wallowa Mountains. One flowed out of the range through the Wallowa Valley. Its snout reached beyond the valley onto the plain, where a series of large moraines built up. The moraines stayed when the ice melted. They held back much of the melting water creating beautiful Wallowa Lake, which reaches back into the mountain valley. The largest of the moraines built by the glaciers here stands 2000 feet above the valley floor. Erratics Have you ever discovered a large boulder sitting in a place where it doesn’t seem to belong? How did it get there? It is possible that a glacier was responsible for putting the boulder in that spot. An erratic is a stone, or boulder, that has been carried from its original place by a glacier, and has been left lying on ground made up of different types of material. For example, a granite erratic may lay on top of a layer of basalt. Erratics can be small enough to put in your pocket, or as big as a house. In the Willamette Valley of Oregon, far from the site of any Ice Age glaciers, there are some large erratics that originated in northern Idaho or Montana. These boulders were trapped in icebergs that were carried into the Willamette Valley on the huge floods. As the icebergs melted, the boulders dropped to the bottom of the lake. The lake later drained, and left the boulders exposed. Glacial Till Glaciers dumped a huge amount of dirt, sand, gravel and rock on the land. In places the layers are thousands of feet thick. Many areas around Puget Sound, the Okanogan Highlands, and near glacial valleys in mountains are blanketed with this layer of debris. Glacial till often can be identified by its mixture of sand, dirt and rocks. Outwash Plains These areas are called outwash plains, because they were the sites of flooding from melting glacial ice. As water poured from the snouts of the glaciers, it carried sand, gravel and silt downstream. Eventually, the water flowed more slowly and the debris being carried was dropped to the bottom. Many low areas were filled with debris, helping to smooth the surface of the land. In some places, such as the southern Puget Sound Lowland, there are vast areas of flat, or gently rolling plains. They are covered by layers of glacial till, although they are far from were any glacier existed. © 1993 by BCS Educational Aids, Inc. LANDFORMS2 9 Glacial Landforms – 1 8. Small, round-shaped lakes created by large chunks of ice are called ______________. 9. Name a large lake that has been formed by a glacier. __________________________ 10. Explain what “channeled scablands” are. ________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________ 11. The Willamette Valley was not covered by Ice Age glaciers. How was it affected by glacial activity? _______________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________ 12. Where did the water in the massive Ice Age floods come from? _________________ _____________________________________________________________________ 13. What large Oregon lake is held in place by a huge moraine? ___________________ _______________________________________________________________________ 14. What is a glacial “erratic”? ______________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________ 15. Rocks, dirt, gravel and sand that have been moved and dumped by glaciers is called ____________________________________________________________________ 16. A great deal of water flowed from continental glaciers. Sometimes it flooded the land and helped smooth the terrain. What do we call area that has been flooded and shaped by glacial water? ____________________________________________________________________ © 1993 by BCS Educational Aids, Inc. LANDFORMS2 10 Valleys When you travel into ranges of hills or mountains, valleys are prominent landforms. It is possible to tell what formed the valleys by looking at their shapes. Valleys are often formed by water erosion. Streams or rivers flow across the land and cut their way into the soil and rock. Stream valleys tend to be V-shaped. They are very narrow at the bottom there the stream flows, and are wider at the top. (As a river valley grows old, however, the floor may widen, also.) When glaciers formed in the mountains, they flowed into river valleys. They cut the valleys deeper, but also widened the floors. The walls became steeper. As a result, glacial valleys are more U-shaped. The Glaciers of the Northwest are now limited to the higher mountain peaks. But, you don’t have to travel far to find landforms created by those great rivers of ice. Thus, it is often possible top detect the presence of an ancient glacier by looking at the shape of a valley it may once of occupied. Glacial Cirque In the mountains at high elevations, it is possible to find the birthplaces of alpine glaciers. An alpine glacier begins in a small depression on the side of a mountain peak. As it grows and grinds away at the land beneath it, the glacier enlarges the depression forming a valley that is shaped like a bowl with a side cut out. This type of valley is called a “glacial cirque.” Some cirques are still occupied by remains of the original glaciers. Others may have only small snowfields during parts of the year. A few are still the source of active glaciers that continue to shape the land. The Glaciers of the Northwest are now limited to the higher mountain peaks. But, you don’t have to travel far to find landforms created by those great rivers of ice. © 1993 by BCS Educational Aids, Inc. LANDFORMS2 11 Glacial Landforms – 2 17. The boxes above show two valleys. One is a glacial valley and one is a river valley. Label each. 18. Explain how you think the valley shown at the right may have been formed. _______________________________________ _____________________________________ _______________________________________ _____________________________________ _______________________________________ _____________________________________ _______________________________________ _____________________________________ 19. What do we call the valley in which an alpine glacier started? ____________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ © 1993 by BCS Educational Aids, Inc. LANDFORMS2 12 Coastal Landforms The ocean is a very powerful force. It exerts itself along the western edge of the Pacific Northwest creating a number of landforms. A drive along the Oregon or Washington coasts takes a person past some of the most spectacular scenery in the nation. All along the coast, powerful waves throw themselves against the land. In some places, they meet a fairly level beach. Often the beach is sandy and may have large dunes between it and the rest of the land. On other parts of the coast, rocky headlands and cliffs rise just behind narrow beaches, or even directly from the water. Here waves smash against the coast and tear at the land, eroding away soil and rock. Eroding the Coast In some places, the breaking waves find outcropping of very hard volcanic rock. Softer materials are worn away faster than the hard rock, and headlands are formed. Over thousands of years, the softer material continues to erode away, and the headlands are left reaching farther into the sea. These became prominent landmarks and have made good sites for building lighthouses. The Oregon coast has many headlands including Heceta Head. Sometimes waves are able to cut a cavern, or tunnel into headlands. Some of these became large caves. Sea Lion Caves is an example, and has become a shelter for some of the large marine mammals living along the coast. When a tunnel is cut all the ways through a headland, a sea arch is formed. These can be found at several places along the coast. One that is often visited is Hole-In-The-Wall, at Rialto Beach in Olympic National Park. Headlands withstand pounding waves. © 1993 by BCS Educational Aids, Inc. LANDFORMS2 13 If wave action is able to carve away land behind the headland, a sea stack is created. Sea stacks may be fairly small in size, or may seem as large as a mountain. One of the most famous is Haystack Rock, at Cannon Beach, Oregon. Sometimes many sea stacks are found close together, and look like a strange forest of rocks standing along the coast. Many sea stacks have become nesting sites, or “rookeries” for coastal birds. Because of that, most are off limits to people. Some Native American Tribes used sea stacks as fortresses to protect themselves from enemies. Although sea stacks have survived, while the land around them has been washed way, they are still only temporary landforms. Eventually, the pounding sea will grind them away. Building Shorelines The waves pounding against headlands eventually grind the rock into tiny bits of sand and silt. This is washed around in the water until it is deposited on the shore. Waves also carry sand that has been brought to the coast by rivers flowing from inland areas. The Columbia River carries a huge amount of silt and sand into the ocean, but even small streams do their part. Sometimes sand that is worn off rocky headlands is carried into nearby sheltered inlets. Often sandy beaches are found in the inlets between headlands. In other places the sand is spread along lengthy stretches of coastline. As the sand builds up, the beaches reach farther into out into the water and protect sand that was deposited earlier farther inland. In some places the wind whips the sand into huge hills, or dunes that look like big waves of sand. Some of the best sand dune areas along the coast stretch from Bandon, north to Florence, Oregon. © 1993 by BCS Educational Aids, Inc. LANDFORMS2 14 Sometimes the sand that is deposited becomes a barrier protecting the mouth of a river or a bay. Such “sand spits” are narrow, ranging from a few hundred feet to a couple of miles wide. They are long: Dungeness Spit, on the Olympic Peninsula, reaches out into the Strait of Juan de Fuca in a graceful arc enclosing a lagoon behind it. The Long Beach Peninsula reaches some 20 miles north from the mouth of the Columbia River and protects Willapa Bay from the sea. Sandy shorelines can change rather quickly. Sometimes people who have built houses near the water are dismayed to find themselves much farther inland after a number of years and instead of stepping out onto the beach from their home, they have a long hike to the water. The opposite can happen too, of course. Sometimes a change in currents will cause sand to be washed away from a beach. Near Grays Harbor, in southwest Washington, a number of homes have been lost to the sea by erosion. The sea, along with the other forces of nature has played an important part in shaping landforms. It continues, every minute of every day and night, to build, carve, and shape the western edge of the Pacific Northwest. © 1993 by BCS Educational Aids, Inc. LANDFORMS2 15 Coastal Landforms 1.Explain why a headland remains jutting into the sea, while land around it is worn away. _______________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________ 2. If a headland becomes surrounded by water, it becomes known as a . . . _______________________________________________________________________ 3. Hole-in-the-Wall is an example f what kind of formation? _____________________ 4. How did some Native American people use sea stacks? ________________________ _______________________________________________________________________ 5. Why are people not allowed on most sea stacks now? _________________________ _______________________________________________________________________ 6. What happens to sand and bits of rock that is eroded from headlands and sea stacks? _______________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________ 7. Sea stacks have stood in some places for thousands of years. Why are they considered “temporary”? ________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________ 8. What large, moving landforms have been created here lots of sand has been deposited? ______________________________________________________________________ 9. What is a spit? ________________________________________________________ © 1993 by BCS Educational Aids, Inc. LANDFORMS2 16