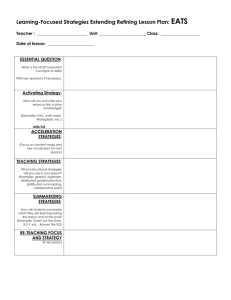

Global Essential Question - Harrisburg School District

advertisement