Final Proposal 1500KB Nov 20 2010 05:36:42 PM

advertisement

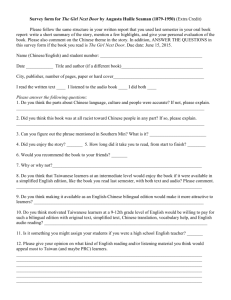

L1 Influence on Chinese Learners’ Acquisition of English Passives L1 Influence on Chinese Learners’ Acquisition of English Passives Yinjuan Mi Ohio University 1 L1 Influence on Chinese Learners’ Acquisition of English Passives 2 1. INTRODUCTION: RESEARCH AREA (5pts) The passive construction has been an essential linguistic phenomenon in the field of grammar. Thus, it draws great attention from many TESOL educators who are dedicated to explore the pedagogically effective method to improve the acquisition of passives for second language (L2) learners. Celce-Murcia and Larsen-Freeman (1999) argue that “although many ESL/EFL grammar books make it seem that the learning challenge for the passive is its form, this is not true from our perspective (p.344)”. They further point out that “it is learning when to use the English passive that represents the greatest long-term challenge to ESL/EFL students (p.344)”. The statement holds for Chinese learners of English as well. A study concerning acquisition of English passives (Chen, 2002) which was based on a database CLEC (containing about one million words produced by Chinese English Learners of different language levels) showed that among different errors the avoidance of using passives is the most common one for all levels of Chinese learners. Contrastive analysis provides a view that first language transfer explains the learners’ difficulty with the target language. Schachter claimed that “contrastive analysis similarities led to errors of production while differences predicted by a priori contrastive analysis led to learner’s nonuse of the target structure” (as cited in Saliger, 1972, p.21). In Chinese, there is a bei construction which typically indicates the passive voice. But it is less used than is English passive construction due to different language systems of two languages, thus Chinese-speaking learners may choose not to use or may not correctly use English passives. One may argue that without comparing with other learners from different L1 backgrounds, it can not be concluded whether it L1 Influence on Chinese Learners’ Acquisition of English Passives 3 is because of language transfer or simply due to learning development. However, Jarvis and Savlenko (2007) claim that the results of numerous studies “have shown quite consistently that learners do rely on the preferred cues from their L1s while interpreting agent-patient relationships in their L2s (p.98)”, and the degree of the L1 influence also depends on their L2 proficiency. Therefore, considering the difficulty Chinese speakers have in appropriately using passives in English, it is worthwhile to further analyze the relationship between the L1 of Chinese and the learners’ acquisition of English passives. 2. AIM/JUSTIFICATION (5pts) There has been a profusion of studies conducted on the influence of L1 on learners’ acquisition of L2. However, as Jarvis and Savlenko (2007) claim the importance of cross-linguistic influence, i.e. language transfer, has not been well acknowledged in the area of syntax compared with phonology and lexis. In terms of English passives, quite a few studies have been done concerning the forms and functions of English passive voice, but few have focused on the acquisition of passives by Chinese speakers in particular. Previous investigations have shown that it is not so much the form but rather the appropriate use of the English passive that creates challenges for Chinese-speaking learners (e.g., Chen & Oller, 2008; Han, 2000; Wang, 2009; Yip, 1995). In the current study, besides collecting spoken data from advanced Chinese learners of English as in the previous study, I will add a group of Spanish-speaking learners of English, a group of Chinese-speaking learners who are at the intermediate level. Additionally, besides interviews, I will also test the participants’ grammaticality L1 Influence on Chinese Learners’ Acquisition of English Passives 4 judgments regarding passive constructions. The purpose of interviewing the group of Spanish-speaking learners is to test if the acquisition of English passives is similar for all second language learners, no matter what their first languages are; and by interviewing the intermediate Chinese-speaking learners of English, I will try to determine how the acquisition of English passives changes with second language proficiency. The purpose of the grammaticality judgment test is to explore whether the participants’ grammatical intuitions in English reflect the grammatical constraints of their first languages. 3. LITERATURE REVIEW (40pts) Previous research has utilized different approaches to analyze the issues that L2 English learners are always faced with during the acquisition of English passives. To some extent, they all agree with the effect of L1 influence in their acquisition of this construction. Yip (1995) examined the case of pseudo-passives, which is considered to be a typical interlanguage structure from Chinese-speaking learners of English. She gave a questionnaire about grammaticality judgments of pseudo-passives to twenty Chinese subjects at a language institution in the U.S., 10 of them at the intermediate level, the other 10 at the advanced level. The results showed that students at a lower level produced fewer correct responses than those at a higher level, accepting at least three out of ten pseudo-passives as grammatical. Although the sample size in this study was small, it did suggest learners with a lower proficiency level tend to accept erroneous pseudo-passives. Given the fact that Chinese is a topic-prominent language which L1 Influence on Chinese Learners’ Acquisition of English Passives 5 emphasizes the topic-comment structure of a sentence not the subject of a sentence as in English, Yip (1995) pointed out that the reason was not due to the lack of knowledge of passive formation but rather the result of transfer of subjectless topic structures from their L1, as “the pseudo-passives accepted were parsed as topic structures analogous to those in Chinese” (p.119). Han (2000) re-examined the case of pseudo-passives based on a two-year longitudinal study which focused on the spontaneous writing from two Chinese speakers who had been living in an English-speaking country for about three years. She found that the well-formed passives and the pseudo-passives coexist in the same linguistic context, by which she claimed that it indicates they have no problem with the form of English passives. This point confirms the understanding of Yip’s research that pseudo-passive is not driven by processing constraints but rather the influence of the L1 structures. Moreover, Han (2000) also carried out a correction task which required the two subjects to rewrite what they thought were incorrect sentences; both of them changed all pseudo-passives into real passives. By providing this evidence, she claimed “pseudo-passive is reincarnated into a target-like passive as a result of increased syntacticization, thereby showing the persistence of the L1 influence” (p.78). However, the pseudo-passive as a malformed passive is not the only error that is made by Chinese-speaking learners. Wang, Y. (2009), by conducting a test on Chinese learners’ acquisition of passive voice, tried to find out which is the most common error in Chinese speakers’ production of passive construction. The subjects of the L1 Influence on Chinese Learners’ Acquisition of English Passives 6 study were 49 sophomores (higher proficiency level) and 55 freshmen (lower proficiency level) in a university of China. They were asked to finish a test which involved grammatical transformation between active and passive structure, multiple choice, and translation between English and Chinese. The results showed that the average passing rate of the sophomore group was 84%, while 71% for the freshmen group. Among all the errors made by these participants, under-passivization, i.e. less use of passives, is the most frequent error type among various other error types. He claimed that the main reason is negative transfer which results from the difference in basic structure between Chinese and English language. Wang, K. (2009) adopted Processability Theory (PT) to investigate the acquisition of English passives by Chinese-speaking learners. He did an interesting experiment which required six Chinese speakers from three different ESL proficiency levels to watch a computer animation clip the Fish Film. The participants’ narration showed that lower level Chinese learners of English could not assign prominence to the semantic patient role by promoting it to the subject function and persisted in using an active construction. But advanced learners performed comparable to native speakers. By utilizing PT as the framework, Wang, K. (2009) explained this phenomenon as follows: language learners’ L2 production is constrained by their language processor, because they can only produce and comprehend the linguistic forms that their language processor can handle. Therefore, language learners initially promote the agent to the grammatical subject to produce sentences in active voice; as their L2 improves, they learn to attribute prominence to the patient to generate passive L1 Influence on Chinese Learners’ Acquisition of English Passives 7 constructions. However, a study conducted by Chen and Oller (2008) presented a partially different result which showed even advanced Chinese learners of English have difficulty in using English passive constructions appropriately as native speakers. They examined the linguistic devices used by Chinese EFL learners who had been in the U.S. for average 30.2 months and native English speakers through narrating a story based on a wordless story book Frog, Where Are You?. The picture book includes 24 pictures with two main characters, a boy and his dog, as well as four secondary figures, a groundhog, an owl, a swarm of bees and a deer. The reason for using this book is it “provides a context for the study of passives and alternative perspective-taking devices” (Chen & Oller, 2008, p.393). They analyzed the transcription of the participants’ narrations based on the degree of agency: “High The bees are chasing the dog. Mid The dog was being chased by the bees. Low The dog was running away (from the bees).” (Chen & Oller, 2008, p.393) They found both that groups did not differ significantly in their choice of event perspectives, topics, and locus of control/effect, but Chinese learners mainly used either a high or low degree of agency, while native speakers used diverse linguistic devices to express different degrees of agency. Chen and Oller adopted the cognitive approach to explain the differences and argued that choice of the passives reflected the speaker’s construal of the whole process of an event from the perspective of an L1 Influence on Chinese Learners’ Acquisition of English Passives 8 affected entity rather than the agent or initiator. Because of the childhood training of construal which favors active voice over passive voice, it leads them to emphasize the agent of an action rather than the patient. It is not difficult to tell by viewing previous studies that there are indeed differences between Chinese-speaking learners and native speakers in using passive constructions. Each study focuses on different types of errors such as pseudo-passives or under-passivizaition, and analyzes them from different aspects, including syntactic similarity, syntacticization, language transfer, processability theory, language construe, etc., yet all of which agree on the effect of L1 influence. 4. RESEARCH QUESTIONS (5pts) 1). What are the differences between Chinese learners and English native speakers in the use of English passives? 2). How do these differences change with L2 proficiency? 3). Are the differences related to Chinese passive structures? 4). What factors influence Chinese learners’ producing of English passives? 5. METHODOLOGY (35pts) a. SUBJECTS/SOURCES In my study there will be 40 participants aging from 18 to 25 who will be selected by the way of snowball sampling. They are: ·10 Chinese-speaking learners with intermediate level of English proficiency from the Ohio Program of Intensive English (OPIE). Their proficiency level is determined by their scores of TOEFL iBT test (i.e. Internet-based Test) and a test given by OPIE. L1 Influence on Chinese Learners’ Acquisition of English Passives 9 ·10 Chinese-speaking learners with advanced level of English proficiency who are graduate students at OU and have been in the USA around one year; their grades of iBT TOEFL are above 100 up to 120 points. ·10 Spanish-speaking learners who have the similar situation as the advanced level of Chinese-speaking learners, i.e. they are graduates, have been in the USA for about one year, and their TOEFL iBT scores are between 100 and 120 points. The purpose of interviewing this group is to help determine if the acquisition of English passives for any L2 learners regardless of their L1 would exhibit similar levels of difficulty and limitation. ·10 native speakers who are undergraduate students at OU as the control group. In order to control the variables like age and social exposure to native speakers, they will be chosen from the students who are at the same age and (if possible) from the same state to have similar cultural background, education level, etc. b. MATERIALS/INSTRUMENTS There will be two tasks given to each participant in the study: story narration, and a test of grammaticality judgment. The text that will be used for the story narration is a wordless picture book named Frog, Where Are You? (Mayer, 1969). It includes 24 pictures with two main characters, a boy and his dog, as well as four secondary figures, a squirrel, an owl, a swarm of bees and a deer. Five episodes of the story book (see the attached Appendix A) will be analyzed, because they can “provides a context for the study of passives and alternative perspective-taking devices” (Chen & Oller, 2008, p.393). Their study L1 Influence on Chinese Learners’ Acquisition of English Passives 10 also showed that these five episodes could successfully elicit passive constructions from English native speakers. These episodes are (Chen and Oller, 2008): Episode I A ground squirrel comes out of a hole and bites the boy’s nose. Episode II The boy falls out of a tree when an owl comes out of a hole in the tree. Episode III The dog is running away from a swarm of bees. Episode IV The boy mistakes the antlers of a deer for a bush and gets carried off. Episode V The deer pitches the boy off a cliff and down into a pond below. The instructions that guide their narration will be kept simple to minimize possible interference from the researcher, and they will be in the form of “This is a story about a boy and a dog”, “What happened in this picture?” and “What’s next?”. Any instructions that may affect the participant’s own perspective of the relation between agent and patient will not be used. For example, “What about the boy?” which was given in the original study (Chen & Oller, 2008) will not be used here, as the researcher believes this may probably elicit the participant to produce a sentence starting with “the boy” as the subject. Their narrations will be recorded using audio recorder and then they will be transcribed. Besides the story book, there will be a test of grammaticality judgment, which is a modified version of Yip’s (1995) test. It consists of 20 sentences for all participants including 10 pseudo-passive sentences and 10 grammatical non-passive sentences as distracters. (See the attached Appendix B.) c. PROCUDURES Before the project, the researcher will pilot the instruments and procedures to L1 Influence on Chinese Learners’ Acquisition of English Passives 11 ensure the quality of the methodology. Subjects of the pilot study will be in similar situations to those in the actual experiment. In the research, all the participants will be shown the picture book page by page to get familiar with the story before narration. Their oral narrations will be audio-recorded individually and then transcribed so as to analyze how they use each verb and the frequency of using passives. After the narration, each participant will be asked to complete the test of grammaticality judgment. Their task is to judge whether each sentence is either grammatical or ungrammatical. If it is ungrammatical, they need to correct the error of the sentence. d. TYPE OF DATA The data will come from the transcriptions of the participants’ oral narrations and the results of the test of grammaticality judgments. In order to analyze how participants use verbs and the frequency of the use of passives, each verb in the story narrations will be analyzed from the perspective of voice, that is either active voice or passive voice. In the test of grammaticality judgment, all the 20 sentences will be graded. But for the purpose of the study, only participants’ responses to verbs in the 20 sentences will be analyzed. Either the judgment or correction of a sentence being wrong, the response will be considered wrong. 6. ANALYSIS (5pts) The study will use descriptive statistics to analyze the data. The analysis for the L1 Influence on Chinese Learners’ Acquisition of English Passives 12 qualitative data will consist of how different groups choose to describe each of the five episodes in terms of voice, and how errors are corrected in the test of grammaticality judgment. The analysis for the quantitative data will be based on how many passives are used in story narrations and how many errors are found and corrected in the grammaticality judgment. Both types of analysis will be compared between Chinese-speaking learners, Spanish-speaking learners, and native speakers, as well as between advanced and intermediate levels of Chinese-speaking learners. 7. ANTICIPATED PROBLEMS/LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY (10pts.) First of all, the time for the research is relatively limited, because the story narration has to be done individually and the transcription process also takes a long time. Without considering the pilot study, there would be a minimum of 40 narrations that need to be transcribed in the end. Also because of the individual narration, it may be difficult to set up a meeting time as everyone has different schedules. In addition, the study is also limited by its sample size. Although there are many Chinese-speaking and Spanish-speaking learners and much more native speakers at OU, the actual number of participants available would be less after considering the control of the variables like age, education background of the participants, and also personal willingness. It is difficult to find enough Spanish-speaking learners at OU who are in the same L2 proficiency level as advanced Chinese-speaking learners; most probably their proficiency level is higher than the Chinese-speaking learners. The researcher has the limitation of being bilingual—Chinese and English, and cannot speak Spanish. In order to analyze Spanish passive structures, the researcher L1 Influence on Chinese Learners’ Acquisition of English Passives 13 will rely on some experts who are good at Spanish grammar and previous studies in the area of Spanish passives. However, the study of the grammar of an unfamiliar foreign language is still a challenge for the researcher. 8. WHAT DO YOU EXPECT TO FIND?/ OR RESEARCH FINDINGS SO FAR (10pts.) The expected findings are: i) The use of passives will increase with the improvement of L2 proficiency. This is expected because the result of a previous study (Wang, 2009) which examined six Chinese speakers from three different ESL proficiency levels showed that as learners’ L2 improves, they learn to attribute prominence to the patient to generate passive constructions. ii) There are indeed differences between Chinese-speaking learners and native speakers in using English passives, for example, the less use of passives for Chinese-speaking learners, and malformed passive sentences for lower L2 proficiency level. iii) The Spanish-speaking learners will use passives in a more native-like way compared to Chinese-speaking learners. Because Spanish and English are cognate languages, and the structure of passive construction in Spanish shares similarities to that in English, so it would be easier for Spanish-speaking learners to acquire English passives. 9. CONCLUSION (10pts) The passive construction is notoriously difficult for L2 learners of English, L1 Influence on Chinese Learners’ Acquisition of English Passives 14 making the acquisition of passives of great interest for both theoretical and pedagogical reasons. For many L2 learners, an understanding of the passive voice requires an understanding of much more than just its form. Having a grasp of the purposes underlying its use is critical for accurate and appropriate passive production. Therefore, it is important for TESOL educators to be aware of the factors influencing the form, meaning and use of passives in both spoken and written English, and to take these factors into account when planning, designing, and providing practice with this construction. 10. REFRENCES (5pts) Celce-Murcia, M. & Larsen-Freeman, D. (1999). The grammar book: An ESL/EFL teacher’s course (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle. Chen, L, & Oller J. W. (2008). The use of passives and alternatives in English by chinese speakers. Cognitive Approaches to Pedagogical Grammar. A Volume in Honor of Rene Dirven, 385–416. Han, Z. (2000). Persistence of the implicit influence of NL: The case of the pseudo-passive. Applied Linguistics. 21(1), 78-105. Jarvis, S., & Pavlenko. A. (2007). Crosslinguistic influence in language and cognition. New York, NY: Routledge. Mayer, M. (1969). Frog, Where are you? New York: Dial Press. Odlin, T. (1989). Language transfer: Cross-linguistic influence in language learning. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Seliger, W. H. (1989). Semantic transfer constraints on the production of English L1 Influence on Chinese Learners’ Acquisition of English Passives 15 passive by Hebrew-English Bilinguals. In Dechert W. H. & Raupach. M. (Eds.), Transfer in language production (pp. 21-33). Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corporation. Wang, K. (2009). Acquiring the passive voice: Online production of the English passive construction by Mandarin speakers. In J.-U. Keßler & D. Keatinge (Eds.), Research in second language acquisition: Empirical evidence across languages (pp.95-119). Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Press. Wang, Y. (2009). Research on three error types of Chinese ESL learners’ acquisition of passive voice. Asian Social Science. 5(12), 134-140. Xiao, R. (2007). What can SLA learn from contrastive corpus linguistics? The case of passive constructions in Chinese learner English. Indonesian Journal of English Language Teaching. 3 (1). Yip, V. (1995). Interlanguage and learnability from Chinese to English. Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins Publishing B.V. L1 Influence on Chinese Learners’ Acquisition of English Passives 16 11. INSTRUMENTS (5pts) Appendix A Story book: Frog, Where Are You? Episode I Episode IV Episode II & III Episode V Appendix B Grammaticality Judgment Test Judge if the following sentences are grammatical. If a sentence is not grammatical, correct the error in the sentence. 1. The workers are building a ship. L1 Influence on Chinese Learners’ Acquisition of English Passives 2. Your name must write on the board. 3. These old clothes can use for cleaning. 4. The news spreads over the town. 5. The children are watching TV. 6. His answers have written in the book. 7. Their company can list in the ten biggest in the world. 8. The mother is feeding her child. 9. The dishes have cleaned after dinner. 10. Most of my food has eaten already. 11. The mirror shattered during the last earthquake. 12. The errors must correct right away. 13. The cake is baking in the oven. 14. The pictures have painted yesterday. 15. The ice melts under the sun. 16. The price of oil increases due to some reason. 17. The books must renew today. 18. The leaders are discussing the problems. 19. The residents have received the letter. 20. The methods can classify into two types. 12. FORMAT (10pts) 13. IRB (5pts) Attached. 17